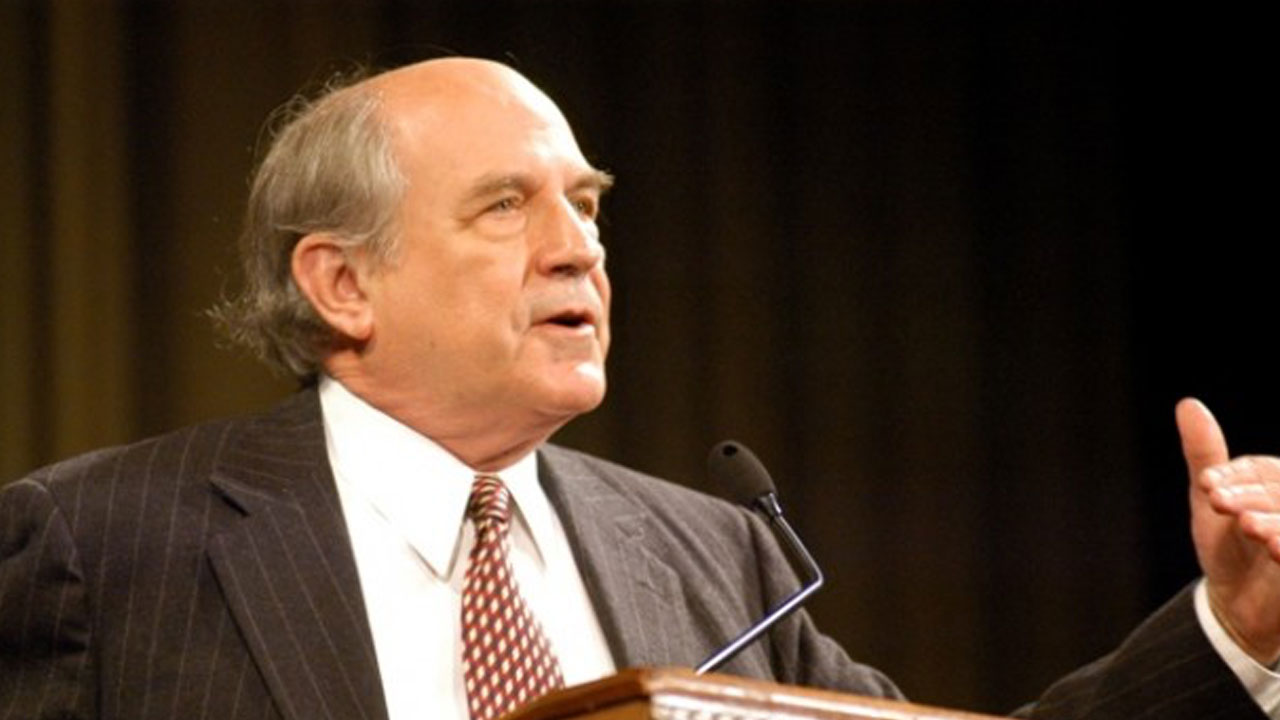

Charles Murray, a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, has become one of the most influential social scientists in America, using racist pseudoscience and misleading statistics to argue that social inequality is caused by the genetic inferiority of the black and Latino communities, women and the poor.

According to Murray, disadvantaged groups are disadvantaged because, on average, they cannot compete with white men, who are intellectually, psychologically and morally superior. Murray advocates the total elimination of the welfare state, affirmative action and the Department of Education, arguing that public policy cannot overcome the innate deficiencies that cause unequal social and educational outcomes.

In his own words

“A huge number of well-meaning whites fear that they are closet racists, and this book tells them they are not. It’s going to make them feel better about things they already think but do not know how to say.”

—regarding his book, Losing Ground, quoted in “Daring Research or Social Science Pornography?: Charles Murray,” The New York Times Magazine, 1994

“The professional consensus is that the United States has experienced dysgenic pressures throughout either most of the century (the optimists) or all of the century (the pessimists). Women of all races and ethnic groups follow this pattern in similar fashion. There is some evidence that blacks and Latinos are experiencing even more severe dysgenic pressures than whites, which could lead to further divergence between whites and other groups in future generations.”

—The Bell Curve, 1994

“Try to imagine a … presidential candidate saying in front of the cameras, ‘One reason that we still have poverty in the United States is that a lot of poor people are born lazy.’ You cannot imagine it because that kind of thing cannot be said. And yet this unimaginable statement merely implies that when we know the complete genetic story, it will turn out that the population below the poverty line in the United States has a configuration of the relevant genetic makeup that is significantly different from the configuration of the population above the poverty line. This is not unimaginable. It is almost certainly true.”

—“Deeper Into the Brain,” National Review, 2000

“You want to have a job training program for welfare mothers? You think that’s going to cure the welfare problem? Well, when you construct that job training program and try to decide what jobs they might qualify for, you had better keep in mind that the mean IQ of welfare mothers is somewhere in the 80s, which means that you have certain limitations in what you’re going to accomplish.”

—Interview on race and IQ, “Think Tank with Ben Wattenberg,” PBS, 1994

Background

Charles Murray has been a central figure in discussions of race, intelligence and public policy since the 1994 publication of The Bell Curve, which Murray co-authored with controversial psychologist Richard Herrnstein, who died shortly before the book’s publication. Murray, a statistically minded sociologist by training, has spent decades working to rehabilitate long-discredited theories of IQ and heredity, turning them into a foundation on which to build a conservative theory of society that rejects equality and egalitarianism.

In Murray’s world, wealth and social power naturally accrue towards a “cognitive elite” made up of high-IQ individuals (who are overwhelmingly white, male, and from well-to-do families), while those on the lower end of the eponymous bell curve form an “underclass” whose misfortunes stem from their low intelligence. According to Murray, the relative differences between the white and black populations of the United States, as well as those between men and women, have nothing to do with discrimination or historical and structural disadvantages, but rather stem from genetic differences between the groups. The Bell Curve, which remains Murray’s most controversial work, firmly lays out Murray’s belief, shared with Herrnstein, that the groups that make up the “underclass” are there solely because of their genes.

Many criticisms of The Bell Curve, most notably Charles Lane’s thorough takedown in The New York Review of Books, have pointed out that Murray’s attempts to link social inequality to genes are based on the work of explicitly racist scientists. In an afterward to the book, Murray rejects criticisms that rest on the fact that “we cite thirteen scholars who have received funding from the Pioneer Fund, founded and run ([Lane] alleged) by men who were Nazi sympathizers, eugenicists, and advocates of white racial superiority.” Murray contends that the racist pseudo-scientists he cites “are some of the most respected psychologists of our time” and that “the relationship between the founder of the Pioneer Fund and today’s Pioneer Fund is roughly analogous to that between Henry Ford and today’s Ford Foundation.”

In fact, the Pioneer Fund’s ties to eugenics and white supremacy are not nearly as historically remote as Murray would have his readers believe. The president of the Pioneer Fund at the time The Bell Curve was written was Harry Weyher, who was a personal friend of the Fund’s founder, Wickliffe Draper, and shared his supposedly archaic views on race; just two months after the initial publication of The Bell Curve, Weyher gave an interview in which he argued, among other things, that desegregation had “wreck[ed] the school system.” Another of the Pioneer Fund’s board members at the time Murray was writing, John Trevor Jr., was also an officer of Coalition of Patriotic Societies, which, during his membership, was indicted for sedition over “pro-Nazi activities” and called for the release of all Nazi war criminals. Despite Murray’s claims, the Pioneer Fund continues to support “research” into race differences conducted by outright white supremacists.

In a similar vein, Murray whitewashes the individual people who provided the intellectual foundation for The Bell Curve. To take only one example, Murray and Herrnstein described Richard Lynn, whose work they relied on more than any other individual, as “a leading scholar of racial and ethnic differences.” In his many subsequent defenses of Lynn, Murray neglected to mention the many serious methodological criticisms of Lynn’s work, or his contributions to white supremacist publications including VDARE.com, American Renaissance and Mankind Quarterly, the last of which Lynn also serves on the editorial staff of.

The Bell Curve not only relied on “tainted sources” like Lynn, but is itself making a fundamentally eugenic argument. The central, and most controversial chapter of the book, focuses on the threat of “dysgenesis,” a term that Murray and Herrnstein claimed to have borrowed from population biology, but which in actuality was coined and has been used exclusively by eugenicists to describe the problem that their policy proposals were intended to fix. Dysgenesis refers to the supposed genetic deterioration of a population, but while Murray and Herrnstein wrote as though it represents mainstream science, dysgenesis is not considered to be a real phenomenon by modern evolutionary biologists. It is widely accepted only among the “scholars of racial and ethnic differences” that appear so prominently in The Bell Curve’s bibliography.

In The Bell Curve and in many of his subsequent articles and books, Murray warns that “dysgenic pressures” will lead eventually to what he calls the “custodial state.” If social and economic status is solely a function of IQ, as Murray and Herrnstein claim, then social stratification will increasingly occur along the lines of innate intelligence. This process would turn the United States into “something resembling a caste society, with the underclass mired ever more firmly at the bottom and the cognitive elite ever more firmly anchored at the top.”

The “custodial state” comes about, according to Murray and Herrnstein, because the elite feels the need to take responsibility for the “underclass,” which, especially in the “contemporary inner city,” lacks “the minimum level of cognitive resources” necessary to sustain a “modern community.” Murray claims that the elite has and will continue to address this problem through the welfare state, segregation and mass incarceration. In The Bell Curve, Murray and Herrnstein describe the custodial state as a “high-tech and more lavish version of the Indian reservation for some substantial minority of the nation’s population,” and suggest that it should be avoided at all costs. As recently as 2005, Murray wrote that the custodial state is “not a happy solution” to crime and other social ills.

Evoking racist Reagan-era attacks on welfare recipients, Murray and Herrnstein contended that government assistance contributes to dysgenic pressures because “for women near the poverty line in most countries in the contemporary West, a baby is either free or even profitable, depending on the specific terms of the welfare system in her country.” According to Murray, the incentives for poor women to game the welfare system by having babies is particularly strong because, thanks to their low IQs, “a ‘career’ is not usually seen as a realistic option.” Welfare in Murray and Herrnstein’s view only exacerbates the intellectual inferiority, and thus the social stratification, it is meant to remedy, and should be abolished.

Just as dangerous as welfare in Murray’s imagination is affirmative action, which he and Herrnstein credited with “leaking a poison into the American soul.” Affirmative action, according to Murray, creates racial tension by promoting black people far beyond their innate capabilities in order to produce a false sense of equality. To bolster this argument, they cite rumors of illiterate or “borderline retarded” black people graduating from police academy, and claim that affirmative action forced major cities like Washington, D.C., and Miami to hire manifestly unqualified black police officers. They even blame affirmative action for crimes committed by police, highlighting a 1985 incident in which police were found to be helping smugglers conceal hundreds of tons of cocaine.

Similarly, they claim that black students are over-represented in the universities, where they get “a large edge in the admissions process and often in scholarship assistance and many of whom, as whites look around their own campus and others, ‘don’t belong there’ academically.” According to Murray and Herrnstein, as white people see less intelligent and competent black people being given preferential treatment, “[t]he tension between what the white elite is supposed to think and what it is actually thinking about race will reach something close to a breaking point,” and a “new, more virulent” racism will emerge, prompting renewed attempts to segregate and isolate the black community.

Despite portraying it as the result of liberal policies he opposes, however, it is clear that the custodial state is precisely the vision of society Murray is working to bring about. The same 2005 article that deplored “abandoning a central tenet of a free society — that everyone can exercise equal responsibility for his or her own life” — was entitled “The Advantages of Social Apartheid,” and its main argument was that, as unpleasant as it sounds, the custodial state is the best solution to social problems. By isolating the “underclass,” the children of the cognitive elite, for example, won’t have to deal with “large numbers of disruptive, foul-mouthed, sexually precocious and sometimes violent classmates.” Similarly, the increasing isolation of the underclass will provide the solution to crime.

Indeed, isolation in the form of mass incarceration has, according to Murray, already solved the crime problem in America: “We didn’t solve the crime problem by learning how to get tough on the causes of crime nor by rehabilitating criminals. We just took them off the streets. As of 2005, more than 2 [million] Americans are incarcerated … it responds to the question ‘Does prison work?’” Again, Murray pretends to find the prospect of mass imprisonment regrettable, and hints that he does not personally believe that the benefits of reduced crime are necessarily worth the cost to the freedom of a large percentage of the population. And again, he is being dishonest; the same year that he wrote “The Advantages of Social Apartheid,” he published a short monograph entitled “Simple Justice,” which argued that crime (or at least the kinds of crime committed by the “underclass”) is not punished harshly enough, and that the purpose of the justice system is to exact revenge against criminals without any consideration of extenuating social circumstances. At the same time, he argued that the justice system unfairly persecutes people who use force to defend their property, arguing that a homeowner who chased a would-be burglar out into the street and murdered them shouldn’t be seen as having done anything wrong.

Murray’s vision of the future and his efforts to bring it about are even more chilling in the context of his early career. Murray started out working in Thailand for the Washington, D.C.-based think tank American Institutes for Research (AIR). While ostensibly conducting basic social science research in remote Thai villages, Murray and his colleagues were working with the U.S. military to develop counter-insurgency programs. AIR’s proposal to the military included plans to develop “stimuli” to bring about desired reactions in the populations; examples given included burning the villagers’ crops, assassinating political figures, “strengthening retaliatory mechanisms and similar preventative measures,” and “neutraliz[ing] the political successes already achieved by groups committed to the ‘wrong’ side,” the last of which “typically involves direct military confrontation.”

The proposal, which is now used as a textbook example of unethical practices in the social sciences, also stated that “[t]he potential applicability of the findings in the United States will also receive special attention. In many of our key domestic programs, especially those directed at disadvantaged sub-cultures, the methodological problems are similar to those described in this proposal; and the application of the Thai findings at home constitutes a potentially most significant project contribution.” As one prominent anthropologist commented, “It takes little imagination to recognize the identities of the ‘disadvantaged subcultures,’ and the circumstances that would be likely to make them targets of such measures.”

While most of the criticism directed at Murray has with good reason focused on the racist elements of his work, his genetic determinism and belief in the inferiority of certain groups extends to the intellectual abilities of women. Unsurprisingly, he holds poor women and women of color in more contempt than he does elite white women; however, in Murray’s mind, even elite women are substantially inferior to men. In the wake of then-Harvard University President Larry Summers’ censure for his 2005 statements about women’s lack of intellectual aptitude, Murray built on Summers’ claims, arguing that “[s]ince we live in an age when students are likely to hear more about Marie Curie than about Albert Einstein, it is worth beginning with a statement of historical fact: women have played a proportionally tiny part in the history of the arts and sciences. Even in the 20th century, women got only 2 percent of the Nobel Prizes in the sciences — a proportion constant for both halves of the century — and 10 percent of the prizes in literature. The Fields Medal, the most prestigious award in mathematics, has been given to 44 people since it originated in 1936. All have been men. … In the humanities, the most abstract field is philosophy — and no woman has been a significant original thinker in any of the world’s great philosophical traditions. In the sciences, the most abstract field is mathematics, where the number of great women mathematicians is approximately two.”