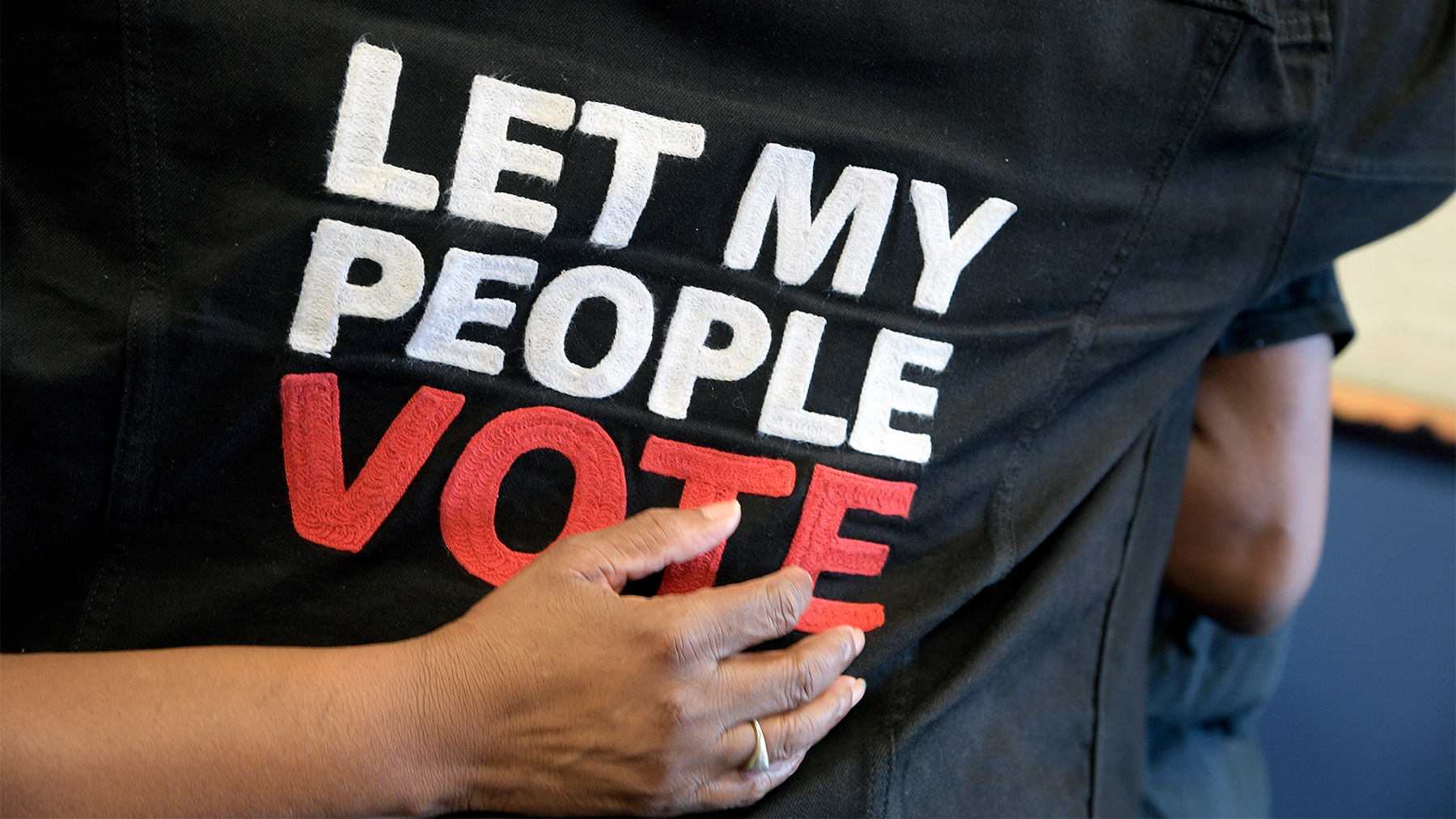

Voting is not a privilege but a right that is essential for a healthy, well-functioning democracy.

It’s a right enshrined in our Constitution, which forbids restricting voting rights based on immutable characteristics, such as race. Our nation’s history, however, is a story of the ongoing battle to ensure this precious right for every American citizen.

After the Civil War, Southern states like Florida expanded criminal codes to include offenses lawmakers believed black people could be most easily convicted and then heightened the penalties for those laws. The result is what we face today – mass incarceration, with more people in U.S. prisons than the entire population of some nations. Florida alone has over 100,000 people in its prisons.

And when formerly incarcerated individuals attempt to reintegrate into society, they are blocked at every turn with limited educational, employment and housing opportunities. These policies persist in large part because the very people affected by them are simultaneously denied the right to vote and don’t have a say in their own future.

Barriers to the ballot box are not new for people of color in this country, especially African Americans. It took the Voting Rights Act of 1965 – one of the nation’s largest enfranchisement of voters – to counter the disenfranchisement effort.

Unfortunately, the battle isn’t over to protect this law.

In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court gutted pre-clearance provisions of the Voting Rights Act, opening the door for states to pass laws that suppress the vote, particularly in states with sizeable African-American populations. And just last month, the high court decided that federal courts have no role in regulating state legislatures’ gross abuses of power when drawing political lines – a decision that former Attorney General Eric Holder said tears “at the fabric of our democracy and puts the interests of the established few above the many.”

And in Mississippi, the SPLC is suing the state to lift a lifetime voting ban for people convicted of certain crimes – a relic of the state’s 1890 constitution, which is still having its intended effect: One in six black adults in the state can’t cast a ballot.

Even recent victories ensuring the right to vote have met with backlash.

In 2018, Florida, a state with the nation’s strictest felony disenfranchisement laws, saw voters overwhelmingly pass Amendment 4, a measure that promised to be the largest expansion of voting rights in the state since the Voting Rights Act. The amendment would restore the right to vote to about 1.4 million Floridians who had served their sentences for felony convictions.

The Southern Poverty Law Center invested heavily in advertising, mail, and canvassing to educate voters and turn out the vote. The amendment was approved by more than 64 percent of the voters. It was an historic moment in a state that’s considered critical in presidential elections but where Republicans narrowly won statewide races for governor and U.S. senate.

But as quickly as the amendment was passed, lawmakers got to work undermining the will of the voters. State legislators passed “enabling legislation” that will force ex-felons to pay all fines, fees, and restitution associated with their sentences before they can regain their right to vote. Cumulatively, that’s more than $1 billion. The bill was signed into law by the governor, creating a hurdle to the ballot box that may prevent as many as 1 million people from voting.

Last week, the SPLC’s Voting Rights Project filed a federal lawsuit over the new law.

It describes how the law is a modern-day poll tax outlawed by the 24th Amendment. The named plaintiffs are African-American women, the group most likely to be adversely affected by the new law. In Florida, one-third of those disenfranchised for felony convictions are black, despite comprising only 16 percent of the general population. What’s more, black Floridians are almost twice as likely to live in poverty as whites.

Underscoring the obstacle lawmakers have created is the reality that women of color are paid less than their male and white female counterparts. Nearly a quarter of all black women in Florida live below the poverty line and the unemployment rate for black women with a felony conviction is more than 43 percent.

Jim Crow’s fingerprints are all over this law and its effect will be painfully clear come Election Day. People of color, particularly black women, will be silenced at the ballot box.

This is not what democracy looks like.

The Editors

P.S. Here are some other pieces we think are valuable this week:

- Digital jail: How electronic monitoring drives defendants into debt from Pro Publica

- Alabama isn’t the only state that punishes pregnant women from The New York Times

- Fact-checking President Trump’s retreat on the census citizenship question from The Washington Post

SPLC’s Weekend Reads are a weekly summary of the most important reporting and commentary from around the country on civil rights, economic and racial inequity, and hate and extremism. Sign up to receive Weekend Reads every Saturday morning.

Photo by The Washington Post/Getty Images