Teaching Hard History

Schools are not adequately teaching the history of American slavery, educators are not sufficiently prepared to teach it, textbooks do not have enough material about it, and – as a result – students lack a basic knowledge of the important role it played in shaping the United States and the impact it continues to have on race relations in America.

Download the report.

Teachers can access resources on teaching American slavery at: www.tolerance.org/hardhistory. The resources are offered to educators at no cost.

by Hasan Kwame Jeffries

In the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution, the Founding Fathers enumerated the lofty goals of their radical experiment in democracy; racial justice, however, was not included in that list. Instead, they embedded protections for slavery and the transatlantic slave trade into the founding document, guaranteeing inequality for generations to come. To achieve the noble aims of the nation’s architects, we the people have to eliminate racial injustice in the present. But we cannot do that until we come to terms with racial injustice in our past, beginning with slavery.

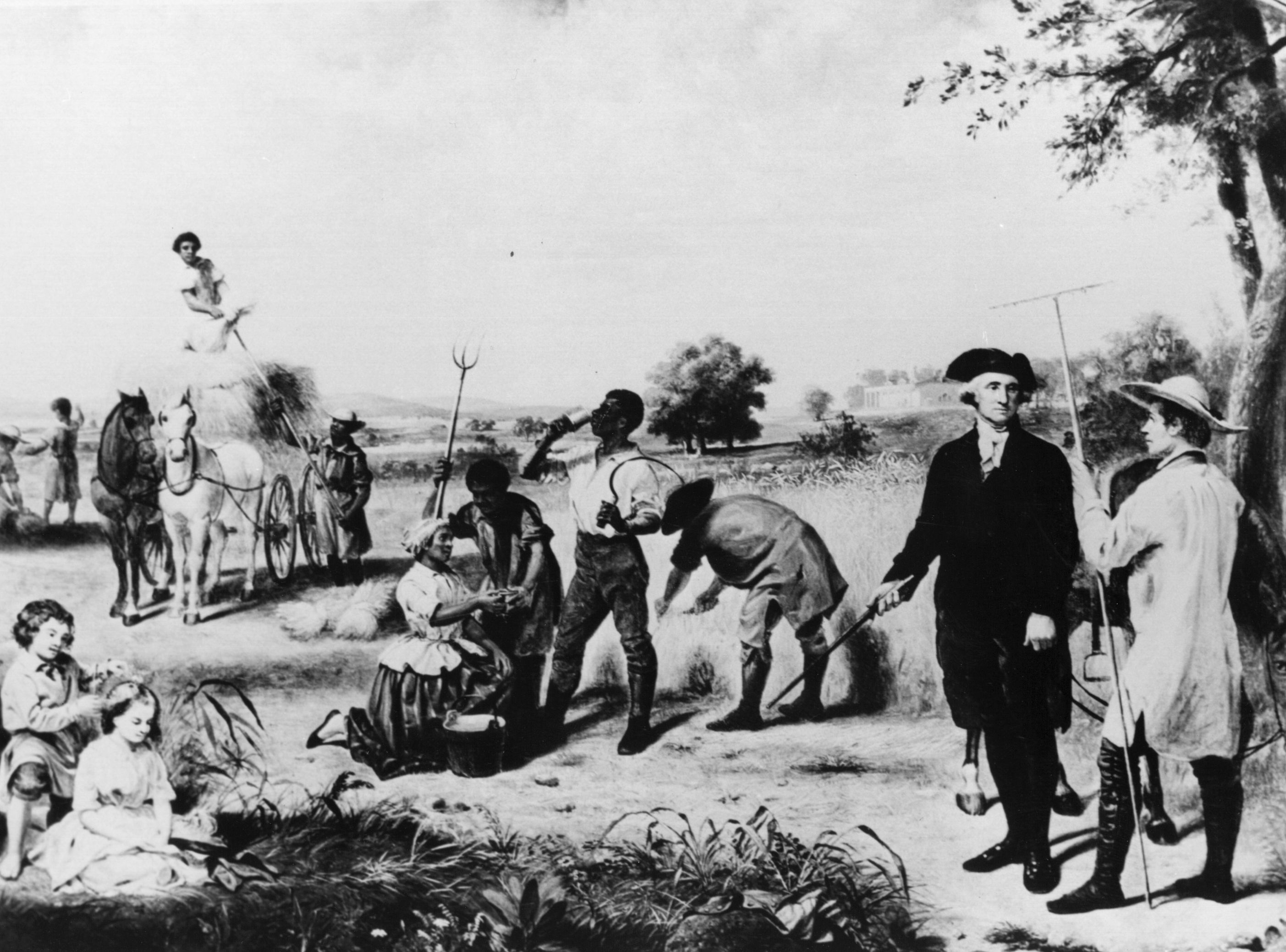

It is often said that slavery was our country’s original sin, but it is much more than that. Slavery is our country’s origin. It was responsible for the growth of the American colonies, transforming them from far-flung, forgotten outposts of the British Empire to glimmering jewels in the crown of England. And slavery was a driving power behind the new nation’s territorial expansion and industrial maturation, making the United States a powerful force in the Americas and beyond.

Slavery was also our country’s Achilles' heel, responsible for its near undoing. When the southern states seceded, they did so expressly to preserve slavery. So wholly dependent were white Southerners on the institution that they took up arms against their own to keep African Americans in bondage. They simply could not allow a world in which they did not have absolute authority to control black labor—and to regulate black behavior.

The central role that slavery played in the development of the United States is beyond dispute. And yet, we the people do not like to talk about slavery, or even think about it, much less teach it or learn it. The implications of doing so unnerve us. If the cornerstone of the Confederacy was slavery, then what does that say about those who revere the people who took up arms to keep African Americans in chains? If James Madison, the principal architect of the Constitution, could hold people in bondage his entire life, refusing to free a single soul even upon his death, then what does that say about our nation’s founders? About our nation itself?

Slavery is hard history. It is hard to comprehend the inhumanity that defined it. It is hard to discuss the violence that sustained it. It is hard to teach the ideology of white supremacy that justified it. And it is hard to learn about those who abided it.

We the people have a deep-seated aversion to hard history because we are uncomfortable with the implications it raises about the past as well as the present.

We the people would much rather have the Disney version of history, in which villains are easily spotted, suffering never lasts long, heroes invariably prevail and life always gets better. We prefer to pick and choose what aspects of the past to hold on to, gladly jettisoning that which makes us uneasy. We enjoy thinking about Thomas Jefferson proclaiming, “All men are created equal.” But we are deeply troubled by the prospect of the enslaved woman Sally Hemings, who bore him six children, declaring, “Me too.”

Literary performer and educator Regie Gibson had the truth of it when he said, “Our problem as Americans is we actually hate history. What we love is nostalgia.”

But our antipathy for hard history is only partly responsible for this sentimental longing for a fictitious past. It is also propelled by political considerations. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, white Southerners looking to bolster white supremacy and justify Jim Crow reimagined the Confederacy as a defender of democracy and protector of white womanhood. To perpetuate this falsehood, they littered the country with monuments to the Lost Cause.

Our preference for nostalgia and for a history that never happened is not without consequence. We miseducate students because of it. Although we teach them that slavery happened, we fail to provide the detail or historical context they need to make sense of its origin, evolution, demise and legacy. And in some cases, we minimize slavery’s significance so much that we render its impact—on people and on the nation—inconsequential. As a result, students lack a basic knowledge and understanding of the institution, evidenced most glaringly by their widespread inability to identify slavery as the central cause of the Civil War.

This is profoundly troubling because American slavery is the key to understanding the complexity of our past. How can we fully comprehend the original intent of the Bill of Rights without acknowledging that its author, James Madison, enslaved other people? How can we understand that foundational document without understanding that its author was well versed not only in the writings of Greek philosophers and Enlightenment thinkers, but also in Virginia’s slave code? How can we ignore the influence of that code, that “bill of rights denied,” which withheld from African Americans the very same civil liberties Madison sought to safeguard for white people?

Our discomfort with hard history and our fondness for historical fiction also lead us to make bad public policy. We choose to ignore the fact that when slavery ended, white Southerners carried the mindsets of enslavers with them into the post-emancipation period, creating new exploitative labor arrangements such as sharecropping, new disenfranchisement mechanisms including literacy tests and new discriminatory social systems, namely Jim Crow. It took African Americans more than a century to eliminate these legal barriers to equality, but that has not been enough to erase race-based disparities in every aspect of American life, from education and employment to wealth and well-being. Public policies tend to treat this racial inequality as a product of poor personal decision-making, rather than acknowledging it as the result of racialized systems and structures that restrict choice and limit opportunity.

Understanding American slavery is vital to understanding racial inequality today. The formal and informal barriers to equal rights erected after emancipation, which defined the parameters of the color line for more than a century, were built on a foundation constructed during slavery. Our narrow understanding of the institution, however, prevents us from seeing this long legacy and leads policymakers to try to fix people instead of addressing the historically rooted causes of their problems.

The intractable nature of racial inequality is a part of the tragedy that is American slavery. But the saga of slavery is not exclusively a story of despair; hard history is not hopeless history. Finding the promise and possibility within this history requires us to consider the lives of the enslaved on their own terms. Trapped in an unimaginable hell, enslaved people forged unbreakable bonds with one another. Indeed, no one knew better the meaning and importance of family and community than the enslaved. They fought back too, in the field and in the house, pushing back against enslavers in ways that ranged from feigned ignorance to flight and armed rebellion. There is no greater hope to be found in American history than in African Americans’ resistance to slavery.

The Founding Fathers were visionaries, but their vision was limited. Slavery blinded them, preventing them from seeing black people as equals. We the people have the opportunity to broaden the founders’ vision, to make racial equality real. But we can no longer avoid the most troubling aspects of our past. We have to have the courage to teach hard history, beginning with slavery. And here’s how.

A graduate of Morehouse College and Duke University, Jeffries holds a Ph.D. in American history with a specialization in African-American history. He is an Associate Professor of History at The Ohio State University and chair of the Teaching Hard History Advisory Board.

by David Blight

This thorough and unprecedented report lays out clearly some 10 “key concepts,” as well as seven “key problems” for teachers and curriculum directors to digest. And they must digest these through study and learning. I applaud the Teaching Tolerance program’s clear-eyed, unafraid quest to name these concepts and problems. They provide a wonderful guide for teachers, as they will also stimulate debate. I also admire the remarkable surveys conducted here; this is a data-driven report and set of prescriptions. It invites new learning and new pedagogy as it also prompts open discussion of how to face this past and gladly, not timidly, teach it. Many of the results are depressing; such surveys almost always are a testimony of ignorance. But therein lies the challenge. Such ignorance of American history is hardly confined to students and American classrooms; it is vividly on display in high offices today in our government.

From directing summer teacher institutes on the history of slavery and abolition for more than 20 years, and from more than 40 years of teaching, first as a public school teacher in Flint, Michigan, for seven years, and then at four different colleges and universities since the 1980s, I can attest to how hungry and needy so many teachers are for knowledge and guidance in this field. We have to feed that hunger, as we also educate both students and teachers. Teachers need what in educational circles is so often called “content.” That means good history, history that does not try to teach to already well-rehearsed simple narratives about American triumphalism, but helps teachers learn and face the difficult, hard questions of our past—slavery, exploitation, violence, dispossession, discrimination and the work that has been done to overcome or thwart those realities. Past and present are always connected in any people’s history; they flow into one another, often in unseen ways, but also in moments of shock and recognition. When it comes to issues of race and the legacies of slavery in America, we are frequently reminded of these truths.

Slavery is not an aberration in American history; it is at the heart of our history, a main event, a central foundational story. Slavery is also ancient; it has existed in all cultures and in all times. Slavery has always tended to evolve in circumstances of an abundance of land or resources, and a scarcity and, therefore, demand for labor. It still exists today in myriad forms the world struggles to fight. The difference in the 21st century is that virtually all forms of trafficking and enslavement today exist in a world where they are illegal. For the two and a half centuries in which American slavery evolved, the systems of slavery operated largely as thoroughly legal practice, buttressed by local law and by the United States Constitution.

In America, our preferred, deep national narratives tend to teach our young that despite our problems in the past, we have been a nation of freedom-loving, inclusive people, accepting the immigrant into the country of multi-ethnic diversity. Our diversity has made us strong; that cannot be denied. But that “composite nation,” as Frederick Douglass called it in the 1870s—a dream and not yet a reality—emerged from generations of what can best be called tyranny. When one studies slavery long enough, in the words of the great scholar David Brion Davis, “we come to realize that tyranny is a central theme of American history, that racial exploitation and racial conflict have been part of the DNA of American culture.” Freedom and tyranny, wrapped in the same historical bundle, feeding upon and making one another, created by the late 18th century a remarkably original nation dedicated to Thomas Jefferson’s idea of the “truths” of natural rights, popular sovereignty, the right of revolution, and human equality, but also built as an edifice designed to protect and expand chattel slavery. Americans do not always like to face the contradictions in their past, but in so many ways, we are our contradictions.

Of all the reasons or justifications used to enslave other human beings, race was late to the long story. Racial slavery came out of the epoch of the slave trade, which of course lasted four centuries in the Atlantic, and likely longer in the Indian Ocean. That said, teachers need to know more of how to tell that story of why slavery became racial in the Americas, and then in the United States. Slavery was not born racial as some kind of original sin; it was made so by people in historical time. Slavery has many roots—economic, social, moral, religious, political and, yes, racial. All can be taught to young people because they can see similar impulses today. This report calls on all involved to learn and teach the history of white supremacist ideology, which provides one of the deep roots of slavery. As the writer Ta-Nehisi Coates argued in 2015, “Race is the child of racism, not the father.” We have a problem of “race” because we have such a long history of making it, of demonstrating how adaptive theories of racial superiority have been to those who would exploit them.

The biggest obstacle to teaching slavery effectively in America is the deep, abiding American need to conceive of and understand our history as “progress,” as the story of a people and a nation that always sought the improvement of mankind, the advancement of liberty and justice, the broadening of pursuits of happiness for all. While there are many real threads to this story—about immigration, about our creeds and ideologies, and about race and emancipation and civil rights, there is also the broad, untidy underside. This is the second of the “key problems” identified in this report, and in the long run, possibly the most challenging.

The point is not to teach American history as a chronicle of shame and oppression. Far from it. The point is to tell American history as a story of real human beings, of power, of vast economic and geographical expansion, of great achievements as well as great dispossession, of human brutality and human reform. The point is also not to merely seek the story of what we are not, but of what we are—a land and a nation built in great part out of the economic and political systems forged in or because of slavery and its expansion. Slavery has much to do with the making of the United States. This can and should be told as a story about human nature generally, and about this place in time specifically. Americans were not and are not inherently racist or slaveholding. We have a history that made our circumstances, as it also at times unmade them. Enslaved Americans were by no means only the brutalized victims of two and a half centuries of oppression; they were a people, of many cultures, who survived, created, imagined and built their worlds. And through the Civil War and emancipation, they had much to do with remaking the United States at its refounding in the 1860s and 1870s.

For young people it is essential that, in learning about this difficult subject, we help them understand that very little about history is determined. History does not happen because of prescriptions etched into our lives and behavior. As humans, we do have many disturbing habits and tendencies. But history is also full of great change. “Change does not roll in on the wheels of inevitability,” wrote Martin Luther King Jr. Change comes because we make it come. The history of slavery is not merely a depressing subject about exploiters and victims, racists and heroic survivors. It is all of those things, but is also a great place to begin to understand our human condition, our nation’s foundations and legacies all round us with which we live every day. Slavery helped make America—to build it—and through cataclysms, its destruction made possible remaking America.

In 1959, surveying how Americans think about their past, James Baldwin wrote that “all our terrible and beautiful history” can seem like it binds us down, that we are “doomed to an unimaginable unreality.” But he refused to accept that conclusion, no matter how “hard” the history. “I prefer to believe,” said Baldwin, “that the day is coming when we will tell the truth about it—and ourselves. On that day … we can call ourselves free men.”

Blight is Class of 1954 Professor of American History and Director, the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance and Abolition at Yale University. He is the author of Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, forthcoming in 2018 from Simon and Schuster.

American enslavement of Africans defined the nature and limits of American liberty; it influenced the creation and development of the major political and social institutions of the nation; and it was a cornerstone of the American prosperity that fueled our industrial revolution. It’s not simply an event in our history; it’s central to our history.

Slavery’s long reach continues into the present day. The persistent and wide socioeconomic and legal disparities that African Americans face today and the backlash that seems to follow every African-American advancement trace their roots to slavery and its aftermath. If we are to understand the world today, we must understand slavery’s history and continuing impact.

Of course, Africans were not the only people enslaved in the Americas. Before setting a course for extermination, colonial powers enslaved Native people en masse. Although this report focuses on the lasting influence of African enslavement, the legacies of racism and white supremacy that plague our country today are a direct result of racial theories that arose to justify enslaving both Native and African people.

Unfortunately, research conducted by the Southern Poverty Law Center in 2017 shows that our schools are failing to teach the hard history of African enslavement. We surveyed U.S. high school seniors and social studies teachers, analyzed a selection of state content standards, and reviewed 10 popular U.S. history textbooks. The research indicates that:

High school seniors struggle on even the most basic questions about American enslavement of Africans.

- Only 8 percent of high school seniors surveyed can identify slavery as the central cause of the Civil War.

- Two-thirds (68 percent) don’t know that it took a constitutional amendment to formally end slavery.

- Fewer than 1 in 4 students (22 percent) can correctly identify how provisions in the Constitution gave advantages to slaveholders.

Teachers are serious about teaching slavery, but there’s a lack of deep coverage of the subject in the classroom.

- Although teachers overwhelmingly (over 90 percent) claim they feel “comfortable” discussing slavery in their classrooms, their responses to open-ended questions reveal profound unease around the topic.

- Fifty-eight percent of teachers find their textbooks inadequate.

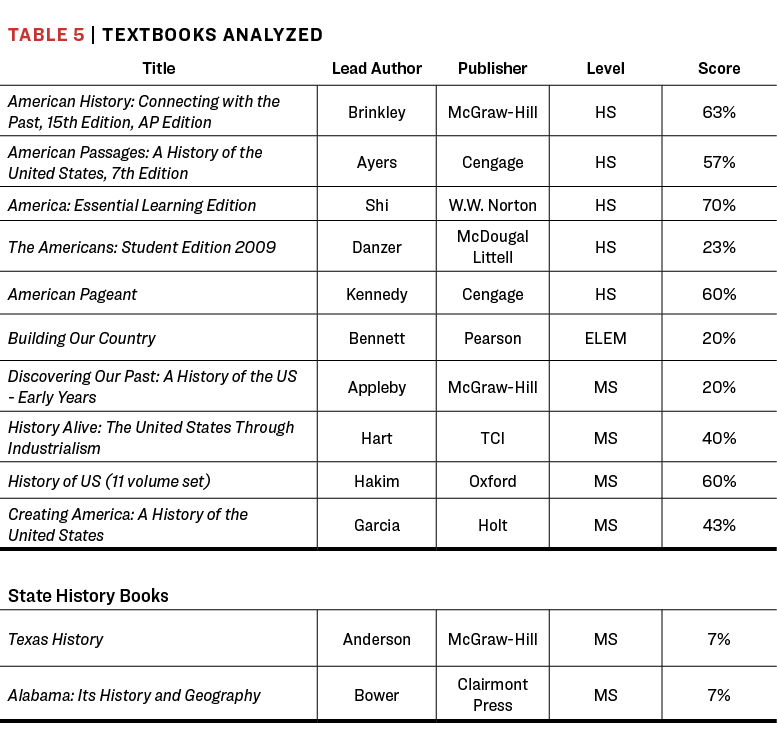

Popular textbooks fail to provide comprehensive coverage of slavery and enslaved peoples.

- The best textbook achieved a score of 70 percent against our rubric of what should be included in the study of American slavery; the average score was 46 percent.

States fail to set appropriately high expectations with their content standards. In a word, the standards are timid.

- Of the 15 sets of state standards we analyzed, none addresses how the ideology of white supremacy rose to justify the institution of slavery; most fail to lay out meaningful requirements for learning about slavery, about the lives of the millions of enslaved people, or about how their labor was essential to the American economy.

- Forty percent of teachers believe their state offers insufficient support for teaching about slavery.

Looking behind the statistics, we see seven key problems with current practices.

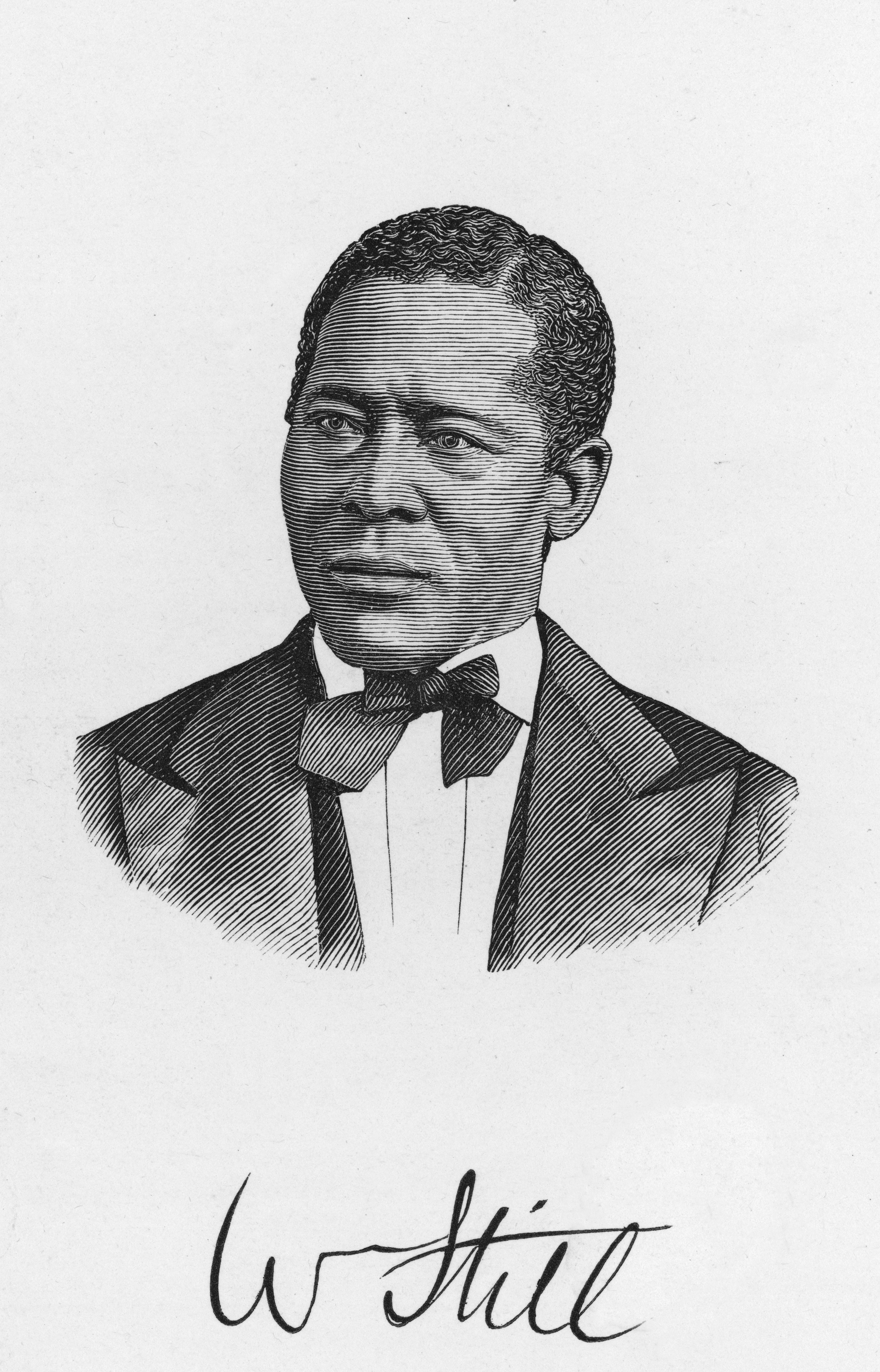

1. We teach about slavery without context, preferring to present the good news before the bad. In elementary school, students learn about the Underground Railroad, about Harriet Tubman or other “feel good” stories, often before they learn about slavery. In high school, there’s overemphasis on Frederick Douglass, abolitionists and the Emancipation Proclamation and little understanding of how slave labor built the nation.

2. We tend to subscribe to a progressive view of American history that can acknowledge flaws only to the extent that they have been addressed and solved. Our vision of growing ever “more perfect” stands in the way of our need to face the continuing legacy of the past.

3. We teach about the American enslavement of Africans as an exclusively southern institution. While it is true that slavery reached its apex in the South during the years before the Civil War, it is also true that slavery existed in all colonies, and in all states when the Declaration of Independence was signed, and that it continued to be interwoven with the economic fate of the nation long into the 19th century.

4. We rarely connect slavery to the ideology that grew up to sustain and protect it: white supremacy. Slavery required white supremacy to persist. In fact, the American ideology of white supremacy, along with accompanying racist dogma, developed precisely to justify the perpetuation of slavery.

5. We often rely on pedagogy poorly suited to the topic. When we asked teachers to tell us about their favorite lesson when teaching about slavery, dozens proudly reported classroom simulations. Simulation of traumatic experiences is not shown to be effective as a learning strategy and can harm vulnerable children.

6. We rarely make connections to the present. How can students develop a meaningful understanding of the rest of American history if they do not understand the scope and lasting impact of enslavement? Reconstruction, the Great Migration, the Harlem Renaissance and the civil rights movement do not make sense when so divorced from the arc of American history.

7. We tend to center on the white experience when we teach about slavery. Too often, the varied, lived experience of enslaved people is neglected while educators focus on the broader political and economic impacts of slavery. Politically and socially, we focus on what white people were doing in the time leading up to the Civil War.

We can and must do better.

To chart a path forward and develop a set of best practices, we assembled a distinguished advisory board of scholars and partnered with institutions and teachers. That collaboration resulted in A Framework for Teaching American Slavery, a comprehensive outline containing concepts that every graduating high school senior should know about the topic, and these four recommendations.

Improve Instruction About American Slavery and Fully Integrate It Into U.S. History. With the release of this report, Teaching Tolerance is making available the framework, a text library of primary sources, and other curricular materials, including 10 Key Concepts that provide teachers a guide toward better instruction.

Use Original Historical Documents. Textbook authors and curriculum developers should expand their repertoire of historical documents beyond the usual narratives to do a better job of representing the diverse voices and experiences of enslaved persons. This will help teachers struggling to navigate the vast array of online resources and archives to put usable documents into classrooms with accompanying instructional material.

Make Textbooks Better. There is considerable work to be done to improve the stories that textbooks tell about the history of American slavery. Texts should do more to convey the realities of slavery throughout the colonies. They should also make intentional connections—good and bad—to the present, by showing both the lasting contributions of African cultures and ideas, as well as the enduring impact of racial oppression on contemporary American life.

Strengthen Curriculum. States, through their standards, supporting frameworks and curriculum requirements, signal to districts, schools and teachers about important material and how to address it. They are failing at conveying the need to teach about the history of slavery. States—and, in local control jurisdictions, districts—should scaffold this learning early and often, refusing to shy away from difficult topics and conversations.

Teaching about slavery is hard. It requires often-difficult conversations about race and a deep understanding of American history. Learning about slavery is essential if we are ever to come to grips with the racial differences that continue to divide our nation.

Now is the time to change the way we teach and learn about slavery.

A fifth-grader is “sold” at a mock slave auction in a New Jersey school. On a day when Georgia students are encouraged to dress in Civil War-era costumes, a white student dressed as a plantation owner tells a 10-year-old black student, “You are my slave.” A California teacher stages a classroom simulation of conditions on a slaver’s ship to provide a “unique learning experience.” A fourth-grader checks with his mother when his English homework asks him to "give three 'good' reasons for slavery." Scholastic, the largest publisher of children’s books, recalls a picture book because of its portrayal of enslaved people as happy and eager to please their enslavers. A popular textbook refers to forcibly imported Africans as “workers.” Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Ben Carson refers to the abducted and enslaved as “immigrants.” Meanwhile, Georgetown University reveals that it achieved early financial security through the sale of nearly 300 enslaved people and promises preferential admission to their descendants, and Yale University renames a residential college previously named after a notorious enslaver.

Slavery isn’t in the past. It’s in the headlines.

slavery.

These recent events reveal, at least in part, how American schools are failing to teach a critical and essential portion of the nation’s legacy—the history and continuing impact of chattel slavery. Research for this report reveals that high school students don’t know much about the history of slavery in the United States, with only 8 percent able to identify it as the central cause of the Civil War. This should not be surprising, given that most adults wrongly identify “states’ rights” as the cause. Widespread ignorance about slavery, the antebellum South and the Confederacy persists to the present day, and is on display in controversies over monument removal in places like New Orleans, Louisiana, and Charlottesville, Virginia, where protests turned deadly in the summer of 2017. Students and adults alike may even hold fringe beliefs, including notions propagated by white nationalists, such as the idea that slavery wasn’t “so bad,” or that the Irish were enslaved. Few Americans acknowledge the role slavery played in states outside the South.

Teachers struggle to do justice to the nation’s legacy of racial injustice. They are poorly served by state standards and frameworks, popular textbooks and even their own academic preparation. For this report, we surveyed more than 1,700 social studies teachers across the country. A bare majority say they feel competent to teach about slavery. Most say that the available resources and preparation programs have failed them. Almost all regret this deficiency, recognizing that teaching the history of slavery is essential. When we reviewed a set of popular history textbooks, we saw why teachers felt a lack of support: Texts fail in key areas, including connecting slavery to the present and portraying the diversity of the experiences of the enslaved. State content standards, which are meant to set clear expectations for instruction, are scattershot at best, often making puzzling choices such as teaching about Harriet Tubman long before slavery, or equivocating on the cause of the Civil War. When we consider the available landscape of materials and expectations, it is no wonder that teachers struggle.

The problem goes beyond poor materials. The subject matter is difficult. We cannot discuss this fundamental part of American history without talking about racism and racialized violence, including sexual violence. When we talk about slavery, we are talking about hundreds of years of institutionalized violence against millions of people. Teachers—like most Americans—struggle to have open and honest conversations about race. How do they talk about slavery’s legacy of racial violence in their classrooms without making their black students feel singled out? How do they discuss it without engendering feelings of guilt, anger or defensiveness among their white students? This unease is particularly acute for white teachers, who make up the overwhelming majority (82 percent) of the U.S. teaching workforce.They want to teach an unsanitized version of American history, but they don’t want to heap negative stories on black students. Making things worse, an increasing number of teachers work in highly segregated classrooms. They face additional challenges. What happens if students come into conflict with each other? What if classroom instruction triggers racial animus? How will such lessons affect children’s sense of self-worth? These kinds of concerns dissuade teachers from confronting big questions and essential history with their students.

Many educators who responded to our survey say that the continuing relevance of slavery’s legacy makes it hard to teach. One Texas teacher comments, “I dislike making this history come alive for my black students. I feel helpless to explain why its repercussions are still with us today.” Others say they have a hard time fitting the story of slavery into the larger narrative of American history, like the Connecticut teacher who notes, “I struggle with talking to kids when they’ve been given the idea that, ’Slavery was a problem, but everything [having to do with race and inequality] is fixed now.’” A number say that slavery is hard to teach because they find it difficult to talk about race. “It is challenging to establish a classroom in which race can be talked about openly,” one Pennsylvania teacher says. “They are ready to label each other as ’racist.’”

A number of teachers worry that the topic can become a flashpoint for racialized conflict in the classroom. “I dislike that it can turn into a race issue, although there are other forms of modern slavery continuing in the present day,” says one educator in Washington state. “I think that hopefully it can be understood in a broader scope so that domination of others for one’s personal gain is wrong in any context.”

Teachers report that white students and students of color have different reactions to the subject. Those working in mixed classrooms explain that they struggle to teach the subject while enfranchising all students. “High school students feel uncomfortable talking about slavery among a mixed group of black and white students," one Florida teacher says. "The white students are afraid they are going to say something that is going to make a black student angry and the black student is going to say something like, ’You whites did this.’ Therefore, neither will openly discuss the topic.”

Other teachers are concerned about the effect teaching about slavery has on their African-American students. One California teacher explains that representations of slavery sometimes have a negative impact on classroom climate and individual students:

It’s tough the way that it affects my African-American students. It makes other students aware of difference and starting to think hierarchically, where they may have never done that before. Although I teach it through the lens of injustice, just the fact that it was a widely accepted practice in our nation seems to give the concept of inferiority more weight in some students’ eyes, like if it happened, then it must be true. Sometimes it gives students the idea to call black students slaves or tell them to go work in the field because of the lack of representation in textbooks. So when students see themselves or their black classmates only represented as slaves in textbooks, that affects their sense of self and how other students view them.

Some teachers admit that teaching about slavery makes them feel their whiteness very keenly. This is particularly true in diverse classrooms, as this Indiana teacher says: “It’s difficult, as a white teacher to majority non-white students, to explain that white people benefited significantly at the very real expense of black people.” Neither is it easy to teach about slavery to white students. Many teachers report this is especially challenging. One Ohio teacher acknowledges that white students’ reactions produce discomfort. “I dislike teaching the topic; white students in my district are very resistive to the idea that racism wasn’t justified or that racism still exists.” A Maine educator reports that he finds it difficult to teach the subject and link it to discussions of white privilege:

I find it painful, and embarrassing (as a white male) to teach about the history of exploitation, abuse, discrimination and outrageous crimes committed against African Americans and other minorities, over many centuries—especially at the hands of white males. I also find it very difficult to convey the concept of white privilege to my white students. While some are able to begin to understand this important concept, many struggle with or actively resist it.

A lack of guidance compounds this unease. No national consensus exists on how to teach about slavery, and there is little leadership. It’s not for lack of resources; an abundance of online historical archives collect and make available original historical documents about slavery. But without structured help, teachers and curriculum planners are left to their own devices, with a patchwork of advice offered by interpretive centers, museums and professional organizations.

It is time to change this state of affairs.

Our work here grew out of an initiative that began in 2011 when we tried to understand how the civil rights movement was being taught. After five years of work on that project, we realized that we needed to go deeper to understand how we teach and learn about our nation’s legacy of racial injustice. For this project, we assembled a diverse advisory board of academic experts to guide our work.

This report maps the ways that we teach and learn about the history of American slavery. It looks beyond anecdotes to collect evidence from students, teachers, textbooks and standards to provide a broad and deep look at what we know about the status quo. To survey students, we contracted with a highly rated independent polling firm to examine what high school seniors knew about slavery. For teachers, we surveyed a cross-section of social studies teachers drawn from Teaching Tolerance subscribers and commercial lists to find out what they taught about slavery. We analyzed popular textbooks using a standardized rubric. We also reviewed 15 sets of state standards: 10 from the top-scoring states in our 2014 Teaching the Movement review of the way state standards cover the civil rights movement and five more to add geographic diversity.

To map this territory, we knew that we would need a framework. Fortunately, in early 2016, the University of Wisconsin Press published Understanding and Teaching American Slavery. Noted historian Ira Berlin’s foreword to that book outlined 10 “essential elements” for bringing slavery into the classroom. We worked with the book’s editors, Bethany Jay and Cynthia Lynn Lyerly, to distill these elements into single sentences, simple statements of what students ought to know. These 10 sentences became the project’s “Key Concepts.”

The Key Concepts inform every aspect of this project, including A Framework for Teaching American Slavery. The framework outlines what every graduating high school senior should know about the history of American slavery. That framework is included in our online resources, released in conjunction with this report. The Key Concepts form the basis of the rubric with which we evaluated popular textbooks (Appendix 3), the survey we administered to high school seniors (Appendix 2), the survey we sent to teachers (Appendix 4), and the way we evaluated state standards. We consulted with a diverse advisory board, assembled for this project, to validate the Key Concepts and A Framework for Teaching American Slavery. (See Appendix 1 for a list of advisory board members and their affiliations.)

Our investigation reveals several discomfiting facts about the ways we teach and learn about American slavery.

We tend to teach about slavery without context.

In elementary school, if slavery is mentioned at all in state content standards, it is generally by implication, with references to the Underground Railroad or other “feel good” stories that deal with slavery’s end, rather than its inception and persistence. Young students learn about liberation before they learn about enslavement; they learn to celebrate the Constitution before learning about the troublesome compromises that made its ratification possible. They may even learn about the Emancipation Proclamation before they learn about the Civil War. Many teachers tell us they avoid teaching about slavery’s violence in elementary school, preferring to focus on positive developments in American history. Yet these early narratives often form the schema by which later learning is acquired, making them difficult to undo.

We tend to teach history as progressive.

Our approach to teaching about slavery has the unfortunate effect of promoting a progressive view of American history that professor of education Terrie Epstein describes as “one in which people successfully and relatively effortlessly challenged inequality.” At risk is that students will leave school without appreciating the scale of slavery and the scope of its continuing effects in American society. As Jelani Cobb, professor of journalism at Columbia University, writes:

The sense of history as a chart of increasing bounties enabled tremendous progress but has left Americans—most of us, anyway—uniquely unsuited to look at ourselves as we truly are and at history for what it is. Our failure to reckon with this past and the centrality of race within it has led us to broadly mistake the clichés of history for novelties of current events.

Young children are able to grapple with complex ideas like segregation and oppression. They have a keen moral sensibility and a strong sense of fairness. There is no reason to believe that they should be shielded from the reality and influence of slavery in American history. In fact, research suggests that acknowledging injustice and oppression results in students being more engaged.

We tend to teach about slavery as an exclusively southern institution.

While it is true that slavery reached its apex in the South during the years before the Civil War, it is also true that slavery existed in all colonies and in all states when the Declaration of Independence was signed. Slavery was the engine for American economic growth for much of its history. The capital for western canals and railroads came from the North, whose wealth—in textiles, shipping, banking and insurance—was in turn built on the slave-based economy even after slavery was abolished in some states. In our survey of high school seniors, very few (12 percent) could correctly answer that slavery was essential to driving the northern economy before the Civil War. Teaching that slavery was “mostly southern” deprives students of the tools they need to grapple with the complicity of northern institutions and citizens in the wider slave-based economy. It also diminishes students’ understanding of the diversity of the experiences of the enslaved, as they tend to believe that all enslaved people lived on large plantations. Finally, this way of teaching also reinforces the false notion that racism (as derived from slavery) was mainly a southern problem, which has implications for understanding racial discrimination outside the South in the century and a half afterward. Textbooks are complicit in this view of history, with a number of popular textbooks offering their most extensive treatment of slavery in coverage of topics such as “Plantation Life” and “King Cotton.”

We fail to discuss the relationship between white supremacy, racism and American slavery.

We often avoid the topics of white supremacy and racist beliefs altogether when talking about slavery, even though slavery required both to persist. In fact, the American ideology of white supremacy, along with accompanying racist dogma, developed precisely to justify the perpetuation of slavery. For this report, we reviewed 15 sets of state standards, including some that our previous research about teaching the history of the civil rights movement had found especially strong. None of these standards mention racism or white supremacy in the context of the history of slavery. In fact, Virginia’s standards use the passive voice when describing the forced importation of labor, saying that Africans “were brought” to the colony. This language—also found frequently in textbooks—portrays actions without agents, slavery without enslavers, history without choice. It removes culpability while focusing on victimhood—a dangerous proposition for teaching meaningful history. Only half of the teachers we surveyed say that they teach about the development of white supremacy to support slavery, and almost all of the textbooks that we reviewed shy away from this topic. Just one approaches it, and even then it declares the question undecided, when history is clear on the causal relationship. To be fair, many teachers in our sample are ahead of both textbooks and standards on this issue. Quite a few teachers in our survey say they want to encourage students to confront white supremacy directly. One teacher from Washington state comments, “I want students to ultimately understand how the institution of slavery and the idea of white supremacy have shaped us as a nation.”

We often rely on pedagogy poorly suited to the topic.

When we asked teachers to tell us about their favorite lesson when teaching about slavery, dozens proudly described classroom simulations. While simulating democratic processes is a proven practice for good civic education, simulation of traumatic experiences is not shown to be effective, and usually triggers families as well as children. Every year the news brings stories of teachers who get into trouble when families complain about this kind of approach. In particular, families of black students are likely (with good reason) to complain about slavery simulations. While no parent wants to see their child auctioned off or forced to lie still in conditions meant to simulate the Middle Passage, it is important to recognize that such simulations are disproportionately traumatic for students of color. Of course, they are inappropriate for any student; simulations cannot begin to convey the horror of slavery and risk trivializing the subject in the minds of students.

We rarely make connections to the present.

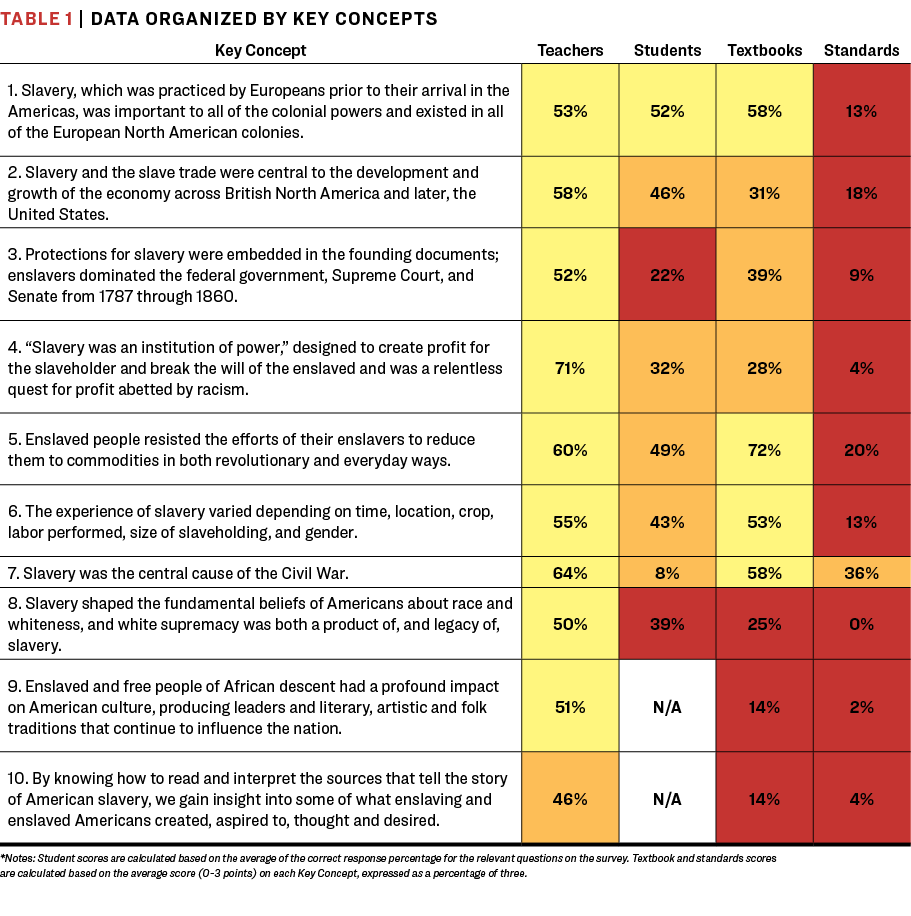

As Table 1 shows, teachers, textbooks and state standards fail to make these essential connections. Slightly more than half (54 percent) of teachers say that they cover the continuing legacy of slavery in today’s society, a legacy that luminaries such as writer and educator Ta-Nehisi Coates and others have covered at length. None of the textbooks that we reviewed make meaningful connections to the present day, either through showing the influence of African culture or by explicating the persistence of structural racism. None of the state standards documents we reviewed make these connections. How can students develop a meaningful understanding of the rest of U.S. history if they do not understand the scope and lasting impact of enslavement? Reconstruction, the Great Migration, the Harlem Renaissance and the civil rights movement do not make sense when so divorced from the arc of American history. We can do better than insisting to students that the horror of slavery is over and the good guys won. We would do well to model instruction after the example of this teacher, who says that the instructional goal when teaching about slavery is “[t]o explain how arguments used to support the slave industry created a context in which African Americans are viewed as different/less than/dangerous, which created a basis for things like Jim Crow laws and workplace discrimination ... and which, today, often show up as unchecked assumptions that then influence people’s actions.”

We tend to center on the white experience when we teach about slavery.

White experience is foregrounded in political, economic and social aspects of the history of American slavery. Politically, textbooks cover the run-up to the Civil War in terms of the major political compromises and conflicts between abolitionists and enslavers, but tend to leave out the perspective of enslaved people. Economically, we look at the power of King Cotton and the mechanics of the Triangular Trade—both deeply influenced by the perspective of enslavers—but these discussions don’t remind learners about where the wealth came from and at what cost. Socially, we learn about differences between the lived experiences of white people in (for example) colonial times, or between planters and small farmers, but the experiences of the enslaved are portrayed as relatively undifferentiated. The enslaved are also voiceless, with very few exceptions given to original historical documents and artifacts in textbooks and in classrooms. Of course, it is difficult to find authentic accounts of slavery from the perspective of the enslaved, but it is not impossible by any stretch of the imagination.

Table 1 summarizes our findings, organized by Key Concept. We have attempted, as much as possible, to make our research findings commensurable; to that end, we have standardized measurements on a 100-point scale so that readers can see the relative extent to which different resources covered the relevant Key Concepts.

Slavery defined the nature and limits of American liberty; it influenced the creation and development of the major political and social institutions of the nation; and it was a cornerstone of the American prosperity that fueled our industrial revolution. It’s not simply an event in our history; it’s central to our history.

Furthermore, as James Baldwin wrote, “History is not the past. It is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history.”

Slavery’s long reach continues into the present day. The persistent and wide socioeconomic and legal disparities that African Americans face today and the backlash that follows every African-American advancement trace their roots to slavery and its aftermath. The scars of slavery and its legacy are seen in our system of mass incarceration, in police violence against black people, and in our easy acceptance of poverty and poor educational opportunities for people of color. Learning about slavery is essential if we are ever to bridge the racial differences that continue to divide our nation.

Now is the time to change the way that we teach and learn about the history of American slavery. The mainstreaming of the so-called “alt-right” and an accompanying surge in white nationalism mean that our nation’s racial fault lines are newly exposed. They are also quite raw, as the reaction to the Black Lives Matter movement and the struggle to take down Confederate monuments have revealed. Even the cause of the Civil War appears to be an unsettled issue, with White House Chief of Staff John Kelly saying in October of 2017 that “compromise” (presumably over slavery) could have avoided conflict, ignoring both the many compromises that led up to war and the horrifying prospect of a compromise that might have left the institution intact. Bargaining with black bodies is not an acceptable way to conduct politics, yet it risks becoming normalized. As The New York Times editorial board wrote:

The consequences of slavery continue to distort and stunt lives in America, so it’s quite right that we should engage in what can be an agonizing conversation about this history. Only when our history is faced squarely can removing Confederate monuments be properly understood, as a small but significant step toward ending the celebration of treason and white supremacy, if not toward ameliorating their effects.

Confronting the United States’ legacy of racial injustice should begin with frank discussions in classrooms about the nature and legacy of slavery. As journalist and political analyst Linda J. Killian has noted, “[w]hite male supremacy is not a new movement.” It has deep roots that stretch back long before the country’s founding. It has pervaded history textbooks for hundreds of years. To understand the present, we must map the past.

Bridging racial divides requires both truth and reconciliation. To tell the truth, teachers must be educated about the history of slavery. The last several decades have witnessed an explosion of new scholarship on slavery and abolition, scholarship that uncovers the institution from the perspective of the enslaved and reveals a world of creativity and resilience that also puts race at the center of American history. Unfortunately, little of this new knowledge has made its way into K–12 classrooms. Textbooks have not kept up with emerging scholarship, and remain bound to the same old narratives and limited primary sources.

Reconciliation requires honest conversations about the nature of white privilege and its persistence despite emancipation, Reconstruction and the civil rights movement. Ultimately, teaching the truth about slavery and the doctrine of white supremacy will be just one step in the right direction, but an essential one. If we don’t get the early history of our country right, we are unlikely to be equipped to do the heavy lifting necessary to bridge racial divides now and in the future. It is a moral necessity if we are to move the country forward toward healing slavery’s persistent wounds.

We have a responsibility to make our nation’s racial history visible, and an opportunity to do so. Teachers need well-constructed tools, well-curated materials, guidance and professional development to deal with this sensitive and charged topic. More importantly, they need the courage that can only come with a national call to teach this history.

This section details the findings of the four ways we collected information for this report: a survey of high school seniors; a survey of teachers; a review of selected state standards; and a review of popular textbooks. Where possible, we have quoted teachers who set aside their valuable time to give us their perspectives.

Student Survey

American high school students do not know much about American slavery. We reached this conclusion after conducting a first-of-its-kind study. In early December 2016, Teaching Tolerance contracted with Survey USA, a highly rated national polling firm, to conduct an online survey of 1,000 American high school seniors. We chose seniors because they have completed nearly 12 years of education, including U.S. history, which is mostly taken in the junior or sophomore years of high school. We asked them what they knew about the history of slavery, using items developed by an expert test-item developer and aligned to our 10 Key Concepts. The items were reviewed by university faculty who are subject-matter experts. A complete list of the survey items can be found in Appendix 2. The 18 items and their answers were randomized for survey takers, so that 20 percent of respondents saw the first answer choice first, 20 percent saw the second answer choice first, and so on. The “not sure” answer always appeared last. To encourage students to answer using their own knowledge rather than consulting other sources, the survey instructions asked students not to use search engines while completing the quiz.

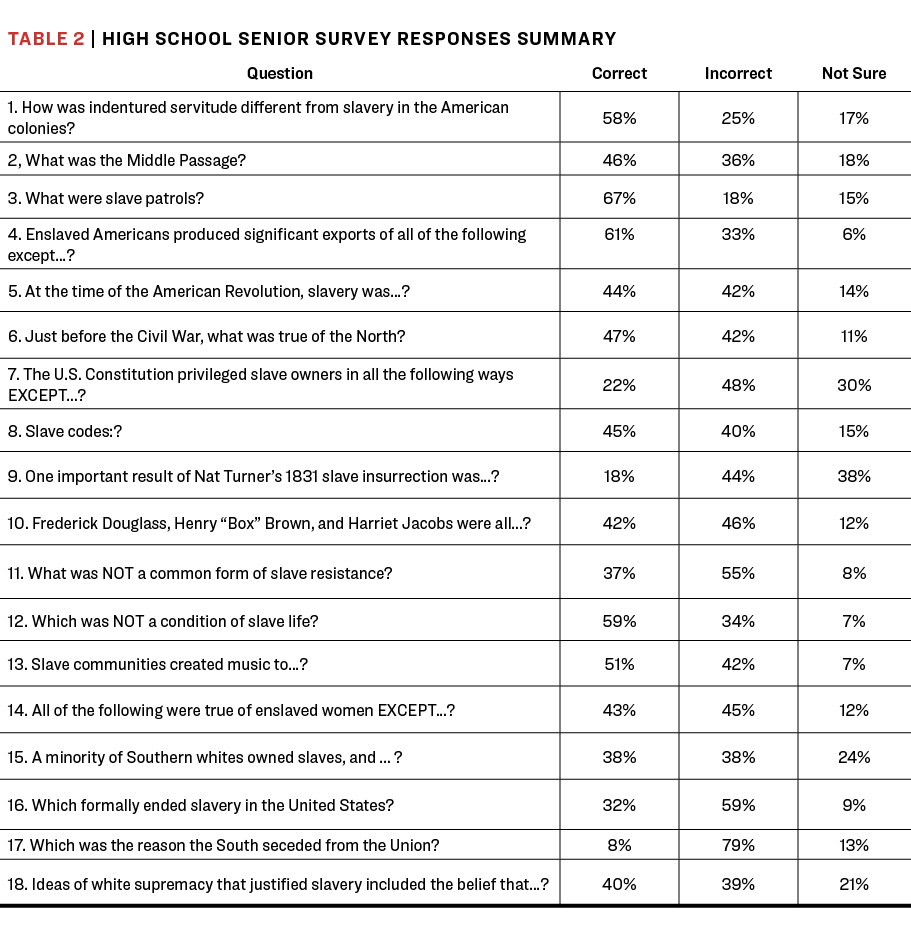

The responses as a whole were dismal, even on very easy items. In no case did more than 67 percent of students identify the correct answer to a given question. For two questions, a plurality of students chose “not sure.” Students were time-stamped as they started and finished the survey, so that those who may have taken advantage of the internet to get help answering questions could be isolated. Mean time to complete the survey was 6 minutes and 30 seconds. Students who completed the survey in 3 minutes or less performed consistently and materially worse than did others. Students who took 7 or more minutes to complete the survey occasionally and in a minority of instances performed better than did those closer to the mean. Suburban respondents consistently outperformed urban and rural respondents. No other meaningful regional differences were observed.

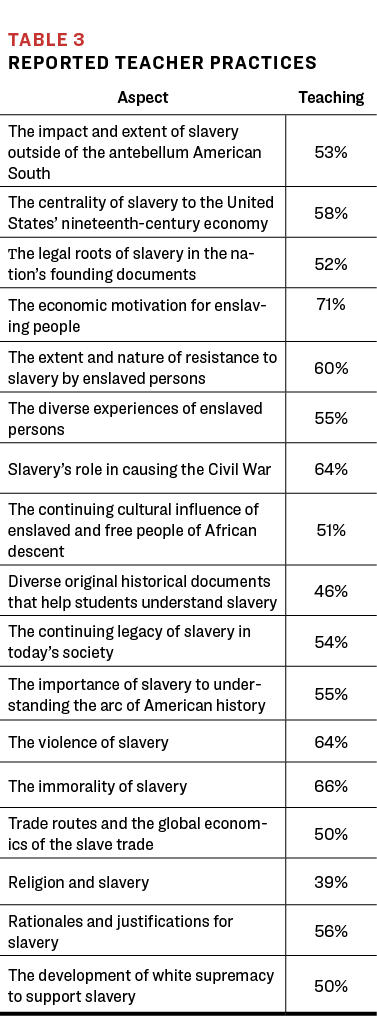

Table 2 indicates the 18 questions and the percentage of high school seniors who chose the correct answer, as well as the percentage who said they were “not sure” of the correct answer.

The most shocking finding of this survey is that only 8 percent of high school seniors can identify slavery as the cause of the Civil War. Almost half of the respondents (48 percent) said tax protests were the cause; it is possible that they confused the Civil War with the Revolutionary War, but that is its own particular problem, given that all of the other questions in the survey were about slavery in some form. That gap shows just how resistant students are to identifying slavery as the central cause of the Civil War.

Some factual errors were surprising. Only 32 percent of students correctly identified the 13th Amendment as the formal end to slavery in the United States, with slightly more (35 percent) choosing the Emancipation Proclamation instead. It was surprising that only 42 percent could identify Frederick Douglass as someone who was formerly enslaved; 29 percent of students said that he, Henry “Box” Brown and Harriet Jacobs were all leaders of slave revolts. It is clear that respondents are unfamiliar with the impact of Nat Turner’s 1831 insurrection, as a plurality (38 percent) said they were not sure of the consequence, and 17 percent said the result was the gradual emancipation of most enslaved people in Virginia. By comparison, only 18 percent chose the correct answer: increased restrictions on enslaved people and expansion of southern militias. Fewer than half of students (46 percent) could correctly identify the Middle Passage as the journey across the Atlantic from Africa to North America.

Teacher Survey

In January 2017, Teaching Tolerance conducted a survey of K–12 teachers to assess their attitudes and perceived self-efficacy related to teaching the history of American slavery. Teachers surveyed were not just Teaching Tolerance affiliates; we also reached out to social studies teachers not aligned with Teaching Tolerance to boost response count and to avoid some of the self-selection problems that might arise with surveying only teachers already predisposed to think about social justice issues. Nevertheless, the majority (90 percent) of responses came from teachers affiliated with Teaching Tolerance. The 1,786 respondents came from across the country. Most (72 percent) say that they teach about slavery in their curriculum.

What Is Taught

The survey asked teachers what aspects of slavery they teach. Table 3 reports the percentages of teachers who say that they teach about a particular aspect of American slavery. These aspects correspond, in large part, to the Key Concepts. While it is heartening to see that most teachers (71 percent) cover the economic motivations behind slavery, it is disappointing to see that just over half (52 percent) teach about the legal roots of slavery in the nation’s founding documents, the diverse experiences of enslaved persons (55 percent), and the continuing legacy of slavery in today’s society (54 percent). Clearly, curriculum scope needs to be improved to more fully capture the history, nuance and importance of slavery in the Americas. It is worth noting that these self-reported accounts do not measure the quality, substance or extent of the coverage given to topics.

We also asked teachers to tell us about the language they use when they talk about slavery in the classroom. Many more teachers (73 percent) use “slaves” rather than “enslaved persons” (49 percent), a term that emphasizes the humanity of enslaved people. This terminology is increasingly used in contemporary scholarship in the field, but has not yet fully trickled down to K–12. More teachers (64 percent) use “owners” rather than “enslavers” (23 percent), reflecting a subtle sanitization of slavery that reifies the idea of the enslaved as property.

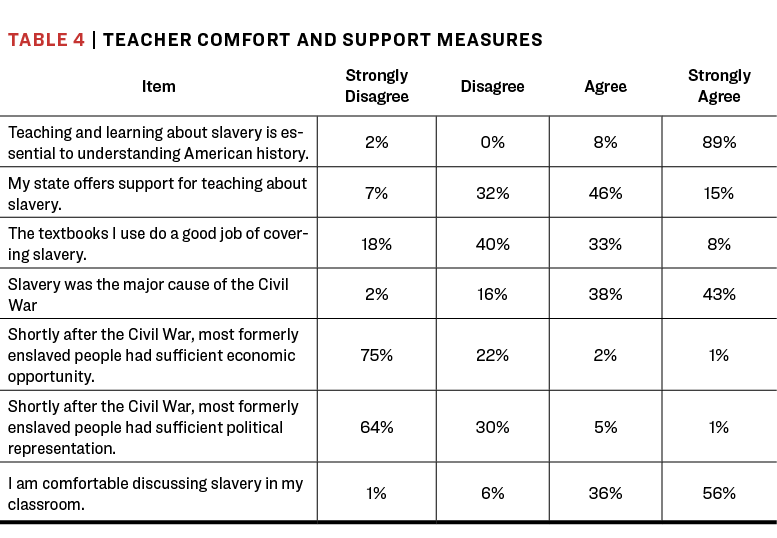

What Teachers Believe and Know

The survey also asked teachers to react to a series of statements about their comfort level, general knowledge and access to support regarding the teaching of slavery. Table 4 shows those results. Almost all teachers (97 percent) agree that learning about slavery is essential to understanding American history and claim (92 percent) they are comfortable talking about slavery in their classroom. The majority (58 percent) are dissatisfied with what textbooks offer, and a large number (39 percent) say their state offers little or no support for teaching about slavery. Almost all teachers performed well on the knowledge questions in this part of the survey.

Teachers also answered four open-ended questions. We asked them:

- their main instructional goal when teaching about slavery

- to identify a favorite lesson to teach about slavery

- what aspects of slavery they like to teach about the least

- what original documents they use to teach about slavery.

Responses to the last question informed our curation of original historical documents now on our website.

Instructional Goals

As might be expected, teachers’ instructional goals are very diverse. A few trends, however, emerged. Many foreground empathy, like the teacher who says, “My main goal is to present the facts and try to get my students to empathize with the rage, fear and sorrow enslaved people experienced.” Others want students to understand that slavery was a harmful institution, like the teacher who wants “to impress upon students the horror that was slavery, and how people were able to overcome it and find their humanity.” A number want students specifically to understand the role of slavery in causing the Civil War, or as background for understanding the civil rights movement. A few are critical of the supports they’re given, like the Arizona teacher who calls out lax coverage in the state’s content standards, or the Oregon teacher who critiques textbooks:

The curriculum standard is the Civil War. Our textbook is nonsense—lots of ahistorical claims of states’ rights, regional climate differences, etc. Slavery is not ignored, but it’s not really addressed as the major, foundational force in U.S. history that it was. My main instructional goal then is to help students understand on a basic level how slavery came to be, why it was unique in the United States, how it became entrenched here, how it impacted so many parts of life during its existence and how it continues to play a very real role in current events today.

Many teachers want students to understand that Africans traveled to what came to be known as the Americas prior to slavery. Some make sure to teach about African kingdoms. Others are very conscious of the students they serve, like this New Jersey teacher:

I have several goals. The first is to understand that African-American history is essential to American history. It is a tough topic, but there is no American history without it. Slavery shaped how this country was built, the foundational documents, and the roots of it can still be seen today. There is still racial tension. I want my students to know that as horrible as it was, there were people who stood up and fought against slavery and fought for civil rights, black and white people. History has many ugly parts, but there were good people who tried to make things right. I want my students to know that Africans were part of the slave trade. I want them to know that people did try to stop it. I want them to know that their history (I teach in a school with almost all African-American and Hispanic students) is not the ugliness of slavery. Their history is rich and full of people who took the opportunity to make their lives better and African Americans are essential to our history.

Some early elementary teachers say they struggle to bring up the subject, and aren’t sure when is too soon to teach about the history of slavery. A Virginia teacher finds the subject necessary as early as second grade. “My main goal in second grade is to teach students that slavery happened,” she says. “I have found that many second-graders come to second grade not knowing about slavery. It is hard to teach about famous Americans like Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, Jr. (second-grade standards) if students don’t understand why there is a history of racial discrimination in the United States, originating with slavery.”

Favorite Lessons

We also asked teachers to describe their favorite lesson. Many say they enjoy using original historical documents, citing Frederick Douglass, Olaudah Equiano and slave narratives collected by the Works Progress Administration during the 1930s. By far the single most popular topic is the Underground Railroad, which dovetails with a number of teachers mentioning that lessons teaching resistance to slavery are their favorites. “I love the stories of the heroes who fought back against slavery,” says one Florida teacher. “I enjoy the stories of slave rebellions, and how students react to them. People like Frederick Douglass, John Brown, Harriet Tubman and Nat Turner have stories that compel children to see how strong and determined the human spirit can be. They help provide a full-scale story of slavery’s evils and the lengths that people will go to to help fight evil.” Many enjoy multimedia resources, including Roots, Amistad and 12 Years a Slave. Some, like this Pennsylvania teacher, say their favorite lessons put human faces on the evils of slavery:

Some of my favorite lessons involve sharing the personal stories/biographies of enslaved people. My students are over 99 percent white. They, like many people, seem immune to statistics and generalizations about the horrors of slavery. However, when I tell them about Phillis Wheatley being kidnapped and “aged” by slavers only by her emerging adult teeth; when I tell them about Sojourner Truth’s toddler-aged sister being sold away from her parents and tossed into a locked tool box on the side of a carriage by her new “master”—THESE stories make some of them weep openly in anger and sorrow.

Some teachers find joy in making connections to the present, especially through music and food. They describe intentionally connecting African-American culture across the centuries to enhance student appreciation. Several, including a teacher from Rhode Island, one from Louisiana and one from Ohio, like making connections to local history.

Debate emerged in the responses about age appropriateness. One California teacher says she takes great care with her second-graders:

I think it is about teaching the building up to it with second-graders. You can’t just start teaching about slavery one day without the forethought behind it and minilessons to make them think critically when you begin to learn about it. Teaching about upstanders, peace, equity and creating a love for one’s self and culture are vital before. There needs to be a great culture that is accepting of each other in order first. My favorite lessons consist of sharing about Harriet Tubman and how phenomenal she was. We learn her story in small groups and read a few whole-group stories as well. We are able to connect other events to the events of slavery soon after, as we learn about other Difference Makers (like Fred Koramatsu, for example). The students don’t grasp it all, but they grasp that it was not okay, that people were treated horribly, and that people came together to stand up against it (ultimately even having a war over it—although the war had other factors as well). But ultimate justice prevailed when people worked together and got their voices heard. We learn that bad things happened before we were born and that it has had an effect on the world at that time and in the future of that event (for example on other events that happened later when some other Difference Makers like Terrence Roberts, Martin Luther King Jr. and Ruby Bridges lived). We also learn that those horrible events were in the past, but it is up to us to shape the future. We can work to make sure everyone is treated kindly and equitably.

Unfortunately, dozens of teachers use “simulations” to teach slavery. In the past, Teaching Tolerance has warned about the danger of classroom simulations, and they are particularly dangerous in this context. More than one teacher employs a “simulated Middle Passage” in the classroom, including one New York teacher who feels “totally comfortable with all aspects” of teaching slavery and reports winning a district award for a Middle Passage simulation. A Florida teacher describes their simulation this way:

I tie the students’ hands and have other students walk them around the room several times and then they are put under a table for about 10 minutes and told not to talk. Lights in the room are turned off. We also put butcher paper over the tables so they cannot see. A discussion follows between the two groups of students as to how they felt and why things were done this way.

Another teacher has students clean cotton while the teacher randomly gives out awards. Others have students role-play as enslaved people and enslavers. Still others conduct “mock slave auctions.” Two teachers have all of their students adopt “slave names.” One teacher has children walk a half mile and back again with a full pail of water, because that is something a book’s protagonist was forced to do.

Least Comfortable Aspects

Finally, we asked teachers to tell us the aspects of slavery that they least like to teach about. Some say that they are comfortable teaching all aspects of slavery and even wish they had more time to cover the subject. “I am not uncomfortable teaching slavery,” says one South Carolina teacher. “I am more disturbed by the fact that so little time is allowed to teach it. More often than not it’s glossed [over] or covered in a couple paragraphs.” Many, like this Texas teacher, are resigned to teaching about slavery because it’s historically necessary. “It’s a dark subject, I don’t think anyone likes reliving past mistakes. I don’t feel comfortable teaching about broken treaties/reservations or Japanese internment camps, either. But you cannot help the truth.”

However, most identify at least one facet that makes them uncomfortable. The most common include the abject cruelty of slavery and accompanying abuse, particularly sexual abuse. The sheer inhumanity of slavery can make it difficult to teach. As one Utah teacher observes, “It is always difficult to discuss the ability of slave owners to treat other human beings as slaves were treated. It is hard for students to understand how someone could do that, and communicating what makes it possible is difficult.”

Teachers say they struggle to communicate a nuanced view of slavery. As this Maryland teacher says, “I don’t feel that even I understand where the proper ’balance’ is between getting across the physical and psychological pain of slavery without losing sight of the efforts made by enslaved people to build emotional, spiritual and family and community resources to cope with the institution.” This isn’t the only kind of balance teachers wrestle with. One Rhode Island educator feels the subject’s importance especially keenly:

This question is hard to answer because the parts of slavery that I least “like” (the parts that enrage me the most) are some of the most important to teach. I appreciate teaching about some of the darkest moments in our country’s history because I know how crucial it is to deeply understand injustices of the past. Teaching about the violent and dehumanizing experiences of enslaved people on slave ships and on plantations is especially difficult. I struggle with being honest and direct about historical truths WHILE not demoralizing or terrifying students.

Here, as is evident in the answers to other questions, teachers wrestle with teaching slavery to elementary school students. Many who responded to the survey are elementary school teachers, and they teach about slavery although they say that it is difficult. This North Carolina teacher discusses working with students in different grades:

It is tricky with elementary school students to discuss slavery because invariably some students are terrified that slavery ever happened in the country where they live, and that it happened to people who look like them. I have to watch for signs of children being under stress because they are scared of the brutality. The fifth-graders generally can talk about it and study more in depth, and the fourth-graders, too, but sometimes it is too overwhelming to go beyond the surface with third grade. I focus on the resistance factor more to avoid the children being scared by man’s humanity to man. I don’t want to steal any child’s innocence, though I want to make sure that the children know the real history of their country.

Nearly all elementary teachers agree that teaching slavery is complicated and difficult. This California educator makes a case for teaching slavery in early elementary by focusing on resistance:

It’s hard to teach it. It takes guts, compassion, reading your students, lots of discussion and uncertainty of what exactly your little second-graders might be wondering or thinking that they aren’t saying. I think it would be a lot easier to just not teach it to be honest. However, I add teaching it in because I realize the significance of understanding early on that it was not okay. That it was unimaginable and yet it happened. We need to learn just how important it is to be kind, considerate and to stand up for ourselves and others (no matter how uncomfortable it might be). I don’t get into the nitty gritty, but we learn a lot about the Underground Railroad and about the importance of helping each other.

Overall, the teachers we surveyed find teaching slavery to be difficult but essential. Although some use troubling teaching practices, the majority are quick to recommend original historical documents, rich audiovisual supplements and other resources. It is clear, however, that teachers need more comprehensive support if they are to teach the essential dimensions of the history of American slavery.

State Standards

We did not conduct a comprehensive review of all state content standards for this project; in this way, this report differs from the Teaching the Movement reports, which examined the state of civil rights movement education state by state. Instead, we chose to look at coverage of slavery in the 10 states that scored well in the 2014 report for their coverage of the civil rights movement: Alabama, California, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Virginia, South Carolina, Oklahoma, North Carolina and New York. We assumed that these states would provide the best examples of coverage of slavery. For additional geographic diversity, we added in Kansas, New Jersey, New Mexico, Washington State and Washington D.C., bringing the total number of states examined to 15.

We found a puzzling and patchwork coverage of slavery. Many states reserve slavery for later grades. Taken as a whole, the documents we examined—both formal standards and supporting documents called frameworks—mostly fail to lay out meaningful requirements for learning about slavery, the lives of the millions of enslaved people or how their labor was essential to the American economy for more than a century of our history. In a word, the standards are timid. There are exceptions. The California frameworks do a good job of covering many of the Key Concepts identified in this report. Overall, however, the various standards tend to cover the “good parts” of the story of slavery—the abolitionist movement being foremost here—rather than the everyday experiences of slavery, its extent and its relationship to the persistent ideology of white supremacy. What follows is a review of the relevant standards for each of the states we examined, with some commentary.

Alabama

The 2010 Alabama Course of Study for Social Studies (revised in 2013) introduces the Civil War in first grade and the Emancipation Proclamation in second grade, but delays the first mention of slavery until third and fourth grade, when it is included in a list of causes of the Civil War. Harriet Tubman is on a second-grade list of exemplary Americans, but there is no mention of the institution she struggled against. This is history without context. It misses an opportunity to give students a full picture of what made figures like Tubman so remarkable, while sanitizing the past. In third and fourth grade, the causes of the Civil War are listed as “sectionalism, slavery, states’ rights and economic disagreements,” a disingenuous representation that obscures slavery’s central role in causing the Civil War, insofar as slavery was the underlying cause of factors like sectionalism, states’ rights and economic disagreements. In fifth and sixth grade, students are asked to “[d]escribe colonial economic life and labor systems in the Americas,” including “[r]ecognizing centers of slave trade in the Western Hemisphere and the establishment of the Triangular Trade Route.” Later, the standards cover the Missouri Compromise and Nat Turner’s insurrection, but not the conditions that caused these events. In high school, abolitionism receives some coverage, but the institution it protested receives only a passing mention in the context of the Triangular Trade. In short, Alabama’s Course of Study fails in its responsibility to set meaningful expectations for learning about the history of American slavery—a history that is essential to understand key events in Alabama’s own history and relevant for a substantial number of Alabama’s students whose lives even today are shaped by this past.

Missing Entirely: Key Concepts 1, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

California

California revised its social studies frameworks in 2016. Here, too, Harriet Tubman is introduced as an American hero (in a sample second-grade lesson and in the third-grade framework) before any mention of slavery. The first time the frameworks mention slavery is in fourth grade, in the context of the Compromise of 1850 and California’s path to statehood. However, the fifth-grade framework does a relatively good job of unpacking slavery as part of early colonial history, encouraging teachers to “engage students in the many different aspects of the institution of slavery.” The framework suggests:

Students can use their growing sense of historical empathy to imagine, discuss, and write about how these young men and women from Africa may have felt, having been stolen from their families, transported across the ocean in a brutal voyage, known as the “Middle Passage,” to a strange land, and then sold into bondage. This is an appropriate time to reflect on the meaning of slavery both as a legal and economic institution and as an extreme violation of human rights.

The fifth-grade framework also encourages teachers to cover resistance by enslaved people and to use primary source documents. California’s eighth-grade framework adds additional details, including the importance of slavery in the compromises that shaped the American Constitution. It encourages students to explore the unique cultures that developed among enslaved peoples and the different faces of resistance. It is refreshingly clear about slavery as the central cause of the Civil War. Although the frameworks could do a better job (for example, they perpetuate the myth that slavery was mostly a southern institution), they serve as a good example of how to teach slavery well.

Missing Entirely: Key Concepts 8 & 9

Florida

Florida’s social studies standards are organized by grade into strands and standards. Each standard has related access points, benchmarks and resources. Slavery is first mentioned in fourth grade, when students are asked to “[i]dentify that Florida was considered a slave state (South) and battles were fought in Florida during the Civil War.” This comes without any context or prior explanation of the institution of slavery. There are missed opportunities before this grade—in second grade, one access point in colonial history asks students to “[r]ecognize reasons why people came to the United States, such as jobs or freedom,” which obviously leaves out people who had no choice. Fifth grade marks the standards’ first substantive coverage of slavery, with mention of the Triangular Trade and other aspects. But “Recognize that slaves were forced to work for others” does little to capture the nuance and horror of slavery as an institution. In eighth grade, students learn about the Civil War. Unfortunately, the standards list only states’ rights and sectional differences as “major causes” of the war. An additional standard implies that slavery was a cause: “Identify factors related to slavery that led to the Civil War, such as the Abolition Movement, Nat Turner’s Rebellion, the Underground Railroad, and southern secession.” This is very poorly written. No serious historian argues that Nat Turner or the Underground Railroad led to the Civil War. Perhaps even more confusing is the high school standard that asks students to “[d]escribe the influence of significant people or groups on Reconstruction,” with a subsequent list that includes Harriet Tubman, whose influence on Reconstruction—if it exists—is lost to history. The standards also portray slavery as an exclusively southern phenomenon. Nowhere do they attempt nuanced or deep coverage of slavery, which is particularly objectionable for a former slave state that also served, briefly, as a refuge for those who sought to escape from slavery.

Missing Entirely: Key Concepts 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

Georgia