When she first heard the clatter outside her house in Royal, Florida, Etta Johnson Huff didn’t think much of it. At 70, the proud woman who lives on the same land acquired by her ancestors after the Civil War is not easily ruffled.

But when she looked out her window that morning this past February, what Huff saw sent her outside in a hurry. Workers hired by the Sumter County government were pulling up the signs that she and more than 150 other residents of the historic Black homesteading community, one of only two still in existence, had put up as part of their efforts to save their heritage. The signs, reading “Community of Royal – Preserve History, Not Industry!” were rapidly filling the bed of a motorized cart, the workers wrenching them out of the ground and flinging them one atop another.

Seconds later Huff, still strong for her years, was running. Overtaking the workers, she grabbed as many signs from the cart as she could, fiercely chastising them all the while.

The workers said they had been told to move the signs because they were in the county right of way, essentially on public property. Huff and other residents – while noting that dozens of other signs advertising real estate and various services in the right of way had been left untouched – hammered their signs back into the ground, slightly farther back from the roadway.

The frustration of that morning was emblematic of the tense push and pull the residents of Royal have been engaged in over the past two years, as they have raced to stave off one threat after another to the history and character of their beloved community, founded by newly emancipated Black homesteaders after the Civil War. Historians say Royal, today home to approximately 1,200 Black residents, may be the only such rural community in the country to survive with its landscape largely unchanged and the original plots overwhelmingly in the hands of descendants of the founding homesteaders.

Huff’s story is just one of several collected in an oral history project as part of the community’s efforts to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The project was spearheaded by Edward González-Tennant, Ph.D., an assistant professor at the University of Texas, Rio Grande Valley, who is the author of the original nomination to the National Register. The Southern Poverty Law Center provided support to this project by producing a series of videos featuring the residents telling their stories.

The videos add texture to what is already a rich historical record of Royal, characterized in the National Register nomination by González-Tennant as “one of the most compelling examples of a rural, historically African American community in Florida.”

In the video: Members of the unincorporated community of approximately 1,200 Black residents in Royal, Florida, discuss how they have sought to preserve the history of Royal from development.

In a sign of its resilience, Black homesteaders and their descendants in Royal were able to hold on to their land even as the Black community in Ocoee, just 50 miles away, was wiped out in 1920 by a white mob, and when Rosewood, another Black community 77 miles away, was burned to the ground by a white mob three years later.

Fighting development pressure

The development pressure has been unrelenting. Royal is just 60 miles south of Gainesville. The Villages, among the largest retirement communities in the country, is just 6 miles away and expanding fast.

First, there was a turnpike extension the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) wanted to route right through Royal. Although that project was eventually abandoned, FDOT is now working on widening parts of I-75 that go through Royal. Then there was the rezoning by county officials – who do not recognize Royal, an unincorporated area, as a historic resource – to accommodate planned industrial, high-density residential, and commercial development in the tranquil farming community.

White landowners, many of whom do not live in Royal, have objected to the inclusion of their property in the historic district.

Apparently acquiescing to the concerns of those landholders, the Florida state preservation office redrew the proposed boundaries of the Royal Rural Historic District in ways that also exclude properties owned historically by Black families descended from the original homesteaders who made Royal distinctive.

Last year, the community turned to the SPLC for help. Since then, the SPLC has been providing legal representation, policy guidance and communications support to uplift the Royal community’s efforts to preserve their history and land. The SPLC represents Young Performing Artists Inc. (YPAs), a nonprofit founded by Royal resident Beverly Steele that originally led the effort to have the community added to the Register.

On behalf of YPAs, the SPLC submitted two petitions to the National Park Service contesting procedural and substantive deficiencies in the state of Florida’s treatment of the nomination. The National Park Service, which administers the Register, has agreed with the SPLC twice, most recently in April, finding that the state failed to adequately justify why it excludes certain Black-owned properties from the historic district despite evidence showing they have long been a part of the community of Royal.

“The residents of this community recognize the importance of these historic boundaries in any listing of Royal on the National Register,” said Malissa Williams, a senior staff attorney with the SPLC’s Economic Justice litigation team. “And that’s why they’re fighting so hard to make sure that they are historically accurate and that they are well documented. The oral histories collected by Dr. González-Tennant provide further support to the historic boundaries. It is our hope that the state will finally get this right, after having the nomination sent back twice by the National Park Service.”

‘It’s national history’

Huff said she sees that the future for both her family and her community is in jeopardy.

“I’m afraid that the United States wants to destroy all Black communities,” Huff said. “When I’m gonna pass on to meet my Jesus, I never know, but I’m worried my grandchildren … will not have the peace, the joy, the happiness of living in just a country community.”

The oral histories are compelling and evocative.

One features Steele, 67, who grew up on land her ancestors acquired under the Homestead Act of 1862 and who, fueled by years of intense research and advocacy, has become the key promoter of the historic preservation efforts. While providing her oral history on video, Steele leads a cameraman through the cemetery where many of Royal’s Black homesteaders are buried. She gestures first to the field right in front of the cemetery where she says developers have plans to build 532 homes. She speaks lovingly of a spring elsewhere on the property where families would come for respite from the heat. And she decries the traffic, noise and dust she says would come with industrial development to disturb the souls of those laid to rest in the cemetery.

“If I asked my grandmother what history meant to her, she would say to me, baby, history cannot be changed. It’s written in the Lamb’s Book of Life – because we’re very spiritual here,” Steele said during an interview with the SPLC. “She would say, ‘If it was good, give God the glory, honor, praise, and thanks. If it was bad, still give God the glory, honor, praise, ask forgiveness and still give thanks, because it is written in the Lamb’s Book of Life.’”

Steele continued, “There’s no need to change history. I feel that the state has tried to do that. You just can’t. It’s American history. It’s national history. It is, you know, living memories.”

Maitland Keiler, 91, is also the subject of one of the oral histories. One of Keiler’s ancestors, Jeff Mathews, who was newly emancipated, hacked down dense thickets to plant fields and make his way, through his labors, into ownership of a government-deeded 40-acre parcel. Speaking with the SPLC after his oral history was documented, Keiler recalled his mother walking 5 or 6 miles to the fields to work every day and the community gathering each year to slaughter hogs and share the smoke-cured meat with families in need.

“That is why this land is so important,” Keiler said. “It is very, very important that we keep this land as long as we can.”

Keiler was one of four Royal residents who gathered on a recent day at the nonprofit enrichment and historical center founded by Steele in 2009 to benefit the community and to pass on its history. Located in a renovated school building that was constructed in 1950 to educate Royal’s children and that was closed after schools integrated, the Alonzo A. Young Sr. Enrichment and Historical Center now houses framed photos of Royal residents, artifacts and documents illuminating the history of Royal.

‘Everybody was family’

Virginia Gadson, 62, raised on stories of her great-grandfather and how he settled in Royal on a 40-acre plot, was at the gathering as well. Growing up in a small house without running water, one of six siblings sleeping two to a room, she told stories about helping her parents and grandparents pick tobacco, watermelons, cantaloupes and cucumbers. She remembered church dinners, playing marbles and watching the men of the town play softball on laid-back Sunday evenings. And there were the times, she remembered, laughing, when she and her siblings would secret away a few nickels from the money they had been given to put in the church collection basket. Walking home in their Sunday best, they would stop at the grocery store and spend them on penny candy, chips and soda pop. It would all be gone by the time they got home, she recalled, their clothes hastily wiped free of crumbs that might give them away.

“Oh, we had a fun time walking home!” Gadson said.

Underlying such times, Gadson said, was the sense of community.

“When I grew up, I thought everybody in the community was related to me,” Gadson said, recalling how one family would share their tomato crop with other families, and in return be gifted perhaps a chicken, some bacon, milk or eggs.

All the kids in the community could visit each other’s houses. When they visited our house, my mom fed them all. That was a lesson, I learned, to love everybody. One of the founding principles in Royal is to show love,” Gadson said. “I thought everybody was family, because that’s how we was taught, that we loved everybody in the community.”

All of that is under threat now, Gadson said, as the pressure of development could consume their community.

“They’re not trying to consider us,” Gadson said. “They’re just trying to get rich on top of us. They don’t worry about our feelings. But this is where we was born. It’s all we know. And we want to continue to be as a community, and we want to try to keep our closeness, our connection to each other.”

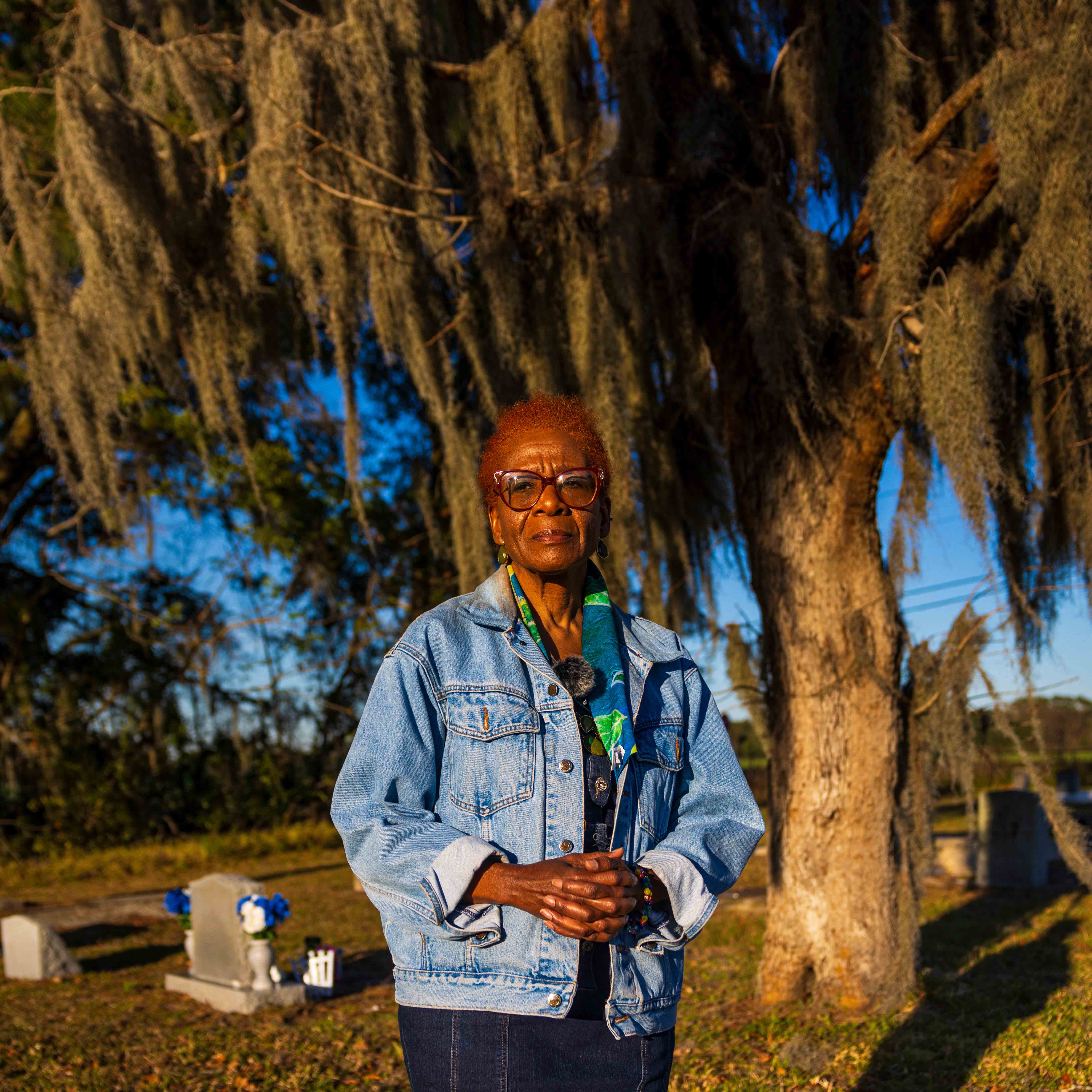

Picture at top: Beverly Steele is a key promoter in efforts to preserve Royal, Florida, founded by formerly enslaved Black homesteaders after the Civil War. (Credit: Saul Martinez)