Two monuments commemorating a Reconstruction-era fight for white supremacy stand on public property in a majority-black town in central Louisiana, the only markers to an 1873 riot that killed 150 African Americans.

And, despite Confederate statues coming down across the country, markers in Colfax seem destined to stay for a while.

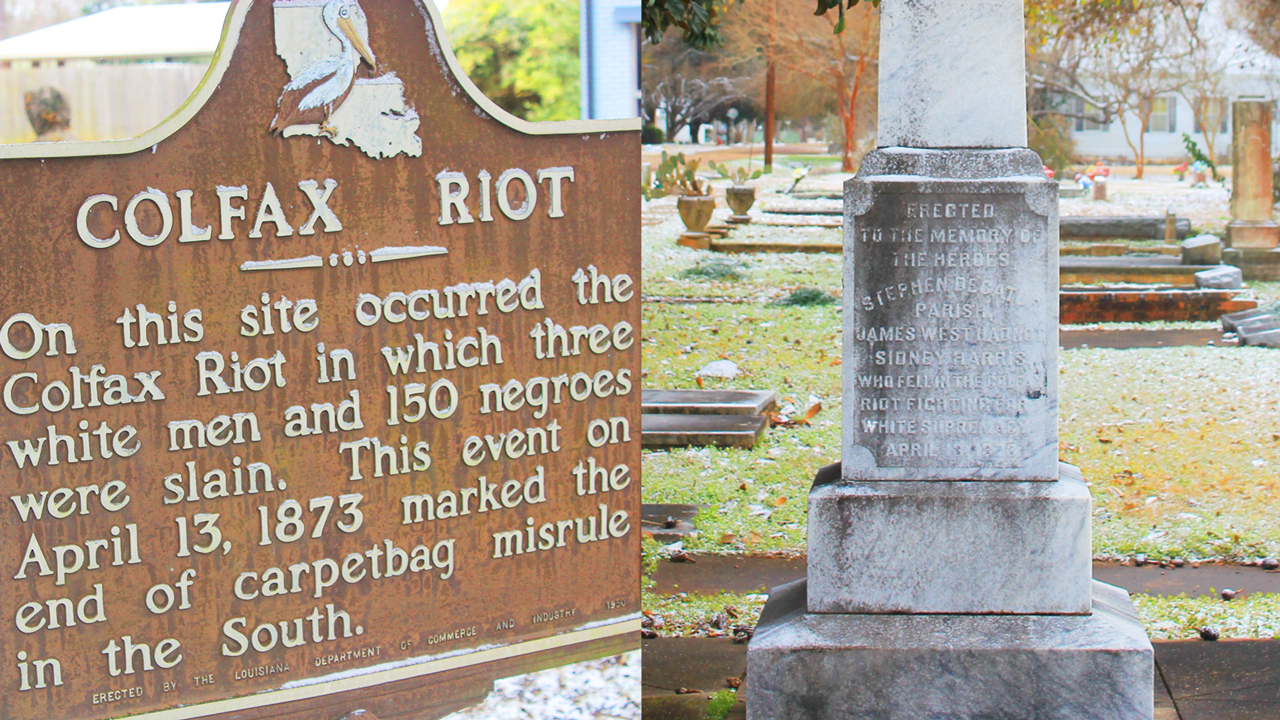

A state-funded marker on the courthouse square, put up in 1950, notes the “Colfax Riot” and says it ended “carpetbag misrule in the South.”

In the city cemetery a few blocks away, a large, white obelisk towers above the other graves and commemorates three white men who died “fighting for white supremacy.”

Ossie Clark, the mayor of the town of 1,500 people, doesn’t object so much to the monuments standing, but instead would like to see a different portrayal of the history.

“It really should say massacre,” Clark told the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Pine trees and poor people

Colfax is the seat of Grant Parish, a nearly four-hour drive from New Orleans, through Cajun country then northwest into the piney woods of central Louisiana. It’s a long way from the tourist meccas of the Bayou State into an area known historically for logging. Now, about a third of the parish sits inside the Kisatchie National Forest.

Grant Parish, named for former U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant, is 85 percent white, 12 percent black and overwhelmingly poor; the per capita income for the parish was $14,410. About 21.5 percent of the population lives below the poverty line.

And the parish seat, Colfax, named for Grant’s vice president, Schuyler Colfax, is racially almost a mirror image to the parish at large – 68 percent black and 30 percent white.

The city is also quite poor, with the per capita income for the town at just $10,155. About 41 percent of the population lives below the poverty line.

Colfax, like many small, Southern towns, is split by railroad tracks. Clark identified the tracks as the marker between the historically white and historically black sections of the city.

The massacre took place on the white side of town, near where the markers now stand.

“It used to be said that only white people could be buried in the city cemetery,” Clark said. “That’s not true. It was never true, but that’s what was believed for a long time.”

The Colfax massacre

After the 1872 gubernatorial election in Louisiana, an all-black militia took control of the Grant Parish Courthouse, fearing that white Democrats would try to take over the local government of a parish evenly divided between blacks and whites.

In response, a group of white Democrats, including former Confederate soldiers and Ku Klux Klansmen, armed with rifles and a small cannon surrounded the courthouse.

They overpowered the predominantly black state militia and a group of Republican freedmen, forcing a surrender.

Most of the freedmen were subsequently killed; nearly 50 were executed later that night after being held as prisoners for several hours.

Estimates of the number of black people killed range from 62 to more than 150 (the number the state uses).

The exact figure is unknown because many of the bodies were thrown into the nearby Red River or hauled away for burial, possibly at mass graves in the area.

Three white men – James West Hadnot, Stephen Decatur Parish and Sidney Harris – were killed.

Those three are memorialized on the monument in the city cemetery and the state highway sign outside the parish courthouse.

There is no similar marker for the black citizens who were killed.

Historian Eric Foner called the Colfax massacre “the bloodiest single instance of racial carnage in the Reconstruction era.”

“Among blacks in Louisiana, the incident was long remembered as proof that in any large confrontation, they stood at a fatal disadvantage,” Foner wrote in Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877

Teaching points

How long will the Colfax markers that honor white supremacy and an end to “carpetbag misrule” stand?

Similar, less overtly white supremacist statues and monuments have come down across the country.

In Memphis, statues of Confederate President Jefferson Davis and former Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest, an early Ku Klux Klan leader, were removed after the city sold the parks where they stood to a private entity.

And, that city’s Liberty Monument, which once stood near the Mississippi River, is also now gone. The memorial marked the Battle of Liberty Place, an 1874 attempt by Democratic White League paramilitary organizations to take control of the government of Louisiana from its Reconstruction Era Republican leadership after a disputed gubernatorial election.

It became a rallying cry for white supremacist David Duke, who called it a symbol of “white pride.”

The memorials in Colfax have not drawn similar attention.

“It’s not a point of contention,” said Clark, who doubles as a teacher and coach at Grant Parish Junior High in nearby Dry Prong.

Messages left for the Louisiana Lieutenant Governor’s office, which oversees tourism, and the state Department of Transportation inquiring about the monuments were not returned.

While Clark would like to see the language changed on the markers, he doesn’t want them taken down.

Instead, Clark would like the markers and massacre to become a teaching point about local history and race relations, particularly given the rise of white nationalism and white supremacy on the current political landscape.

“You don’t spend a lot of time on it in school,” Clark said of ugly historical moments such as the massacre. “It’s not taught by most parents today.”

Leave the markers, Clark said. Let others learn from the mistakes of the past.

“I really wish the people in this town would come together and have a conversation,” Clark said. “I’m always hopeful.”