Last Saturday, as fluorescent lights illuminated a sea of black and gold gowns, East Side and Cleveland High Schools conferred degrees on their graduating seniors for the last time.

Their commencement took place a year and a week after a federal judge ordered the Cleveland School District — located in the heart of the historically black Mississippi Delta — to consolidate its two high schools to remedy the community’s longstanding inability to integrate its schools.

Three years earlier, a federal court had created a plan that allowed families to choose the school they wanted their children to attend. But “while plenty of black families took the opportunity to enroll in the district’s historically white schools, the reverse never happened,” Bracey Harris reported for The Clarion-Ledger. The result was one racially mixed school, Cleveland High, and one all-black one, East Side High.

The district’s “delay in desegregation has deprived generations of students of the constitutionally guaranteed right to an integrated education,” wrote U.S. District Judge Debra M. Brown in her 2016 opinion. It is the school district’s duty “to ensure that not one more student suffers under this burden.”

Many school districts around the country share that duty. According to federal data released last year, many have yet to fulfill it.

In 2016, the Government Accountability Office reported that the number of high-poverty schools serving primarily black and brown students more than doubled between 2001 and 2014. Today, nearly half of all black students attend majority-black schools.

It’s been more than half a century since the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” So why are schools resegregating?

In part, it’s because federal courts are no longer mandating their desegregation.

“Since the 1990s, hundreds of school districts have been released from court-ordered desegregation plans,” Emma Brown wrote for The Washington Post last year, “making way for renewed divisions by race and class.”

In Mississippi, schools are starkly unequal. A strong education clause in the state’s post-Civil War constitution guaranteed a “uniform system of free public schools” for all children, regardless of race. But the rights guaranteed under that clause have been diluted time and again. Today, the state’s schools are some of the most underfunded in the country — and they are anything but “uniform.” All of the state’s F-rated schools, in fact, have overwhelmingly African-American student bodies, while the top five highest-performing school districts are predominantly white.

Segregating poor, black and Hispanic students from white and wealthy ones is not only intrinsically problematic, it means that they do not get the same high-quality resources as students at wealthier schools.

That’s what Dorothy Haymer discovered at Webster Elementary in Yazoo City, Mississippi, where her 6-year-old daughter is in kindergarten. Haymer spent $100 of her own money this year on sanitary supplies for the school, which lacks textbooks, literature, basic supplies, experienced teachers, sports, tutoring programs, and even toilet paper.

At Raines Elementary in Jackson, Precious Hughes describes similar conditions. It’s “old, dark and gloomy – like a jail,” she says, with peeling paint, water stains, and expired lunches.

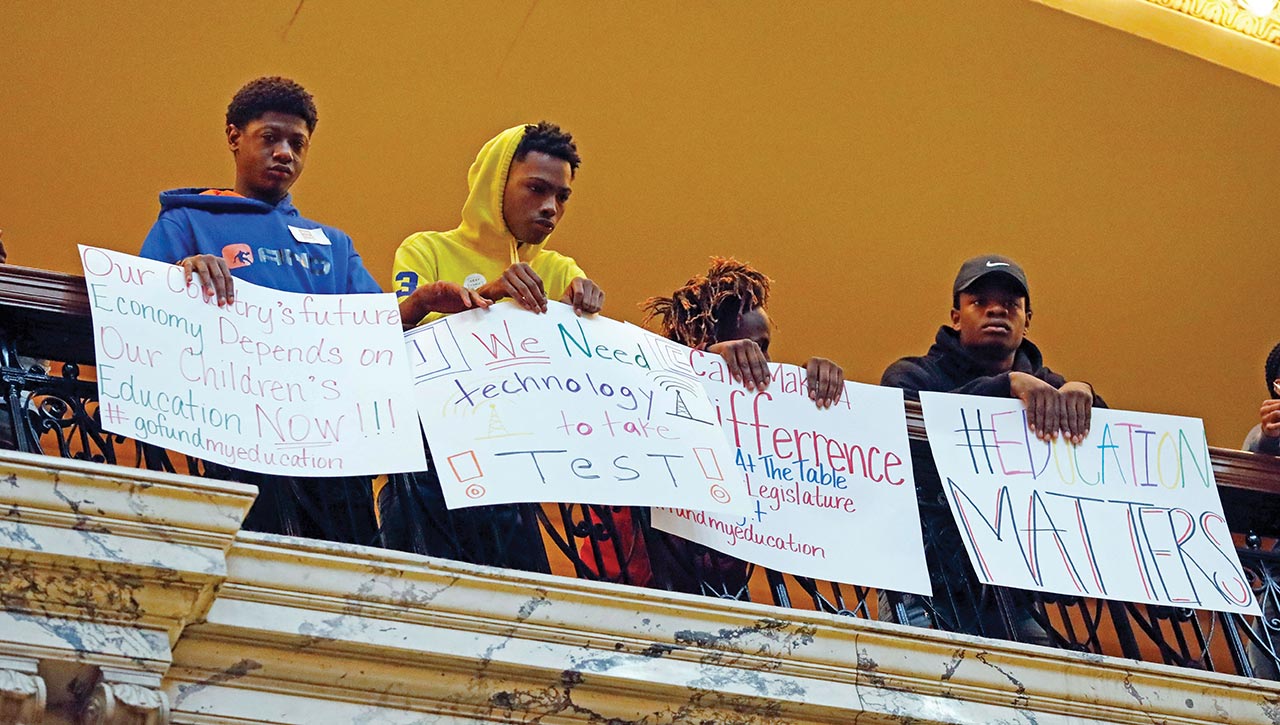

Hughes and Haymer are two of the plaintiffs in a lawsuit that we filed against Mississippi this week for repeatedly violating its obligation to provide students with a “uniform” education.

“These children deserve what the state promised: public schools that treat all children equally no matter their race,” says Indigo Williams, another plaintiff in our suit.

That’s what graduating seniors in Cleveland, Mississippi, say they hope will come out of the merger of their two high schools.

“It’s emotional,” East Side graduate Natashia Washington told The Clarion-Ledger, “but better things are to come for Cleveland.”

Students elsewhere in Mississippi ought to be able to expect the same.

The Editors.

PS Here are some other pieces this week that we think are valuable:

- How the Swastika Became A Confederate Flag by Brent Staples for The New York Times

- The Poisoned Generation by Vann R. Newkirk for The Atlantic

- The Cost of Caring: The lives of the immigrant women who tend to others by Rachel Aviv for The New Yorker

- Fostering Failure: How shelters criminalize children by Karen de Sá, Joaquin Palmonio and Cynthia Dizikes for San Francisco Chronicle

- Black parents use Civil War-era law to challenge Mississippi’s ‘inequitable’ schools by Emma Brown for The Washington Post

SPLC’s Weekend Reads are a weekly summary of the most important reporting and commentary from around the country on civil rights, economic and racial inequity, and hate and extremism. Sign up to receive Weekend Reads every Saturday morning.