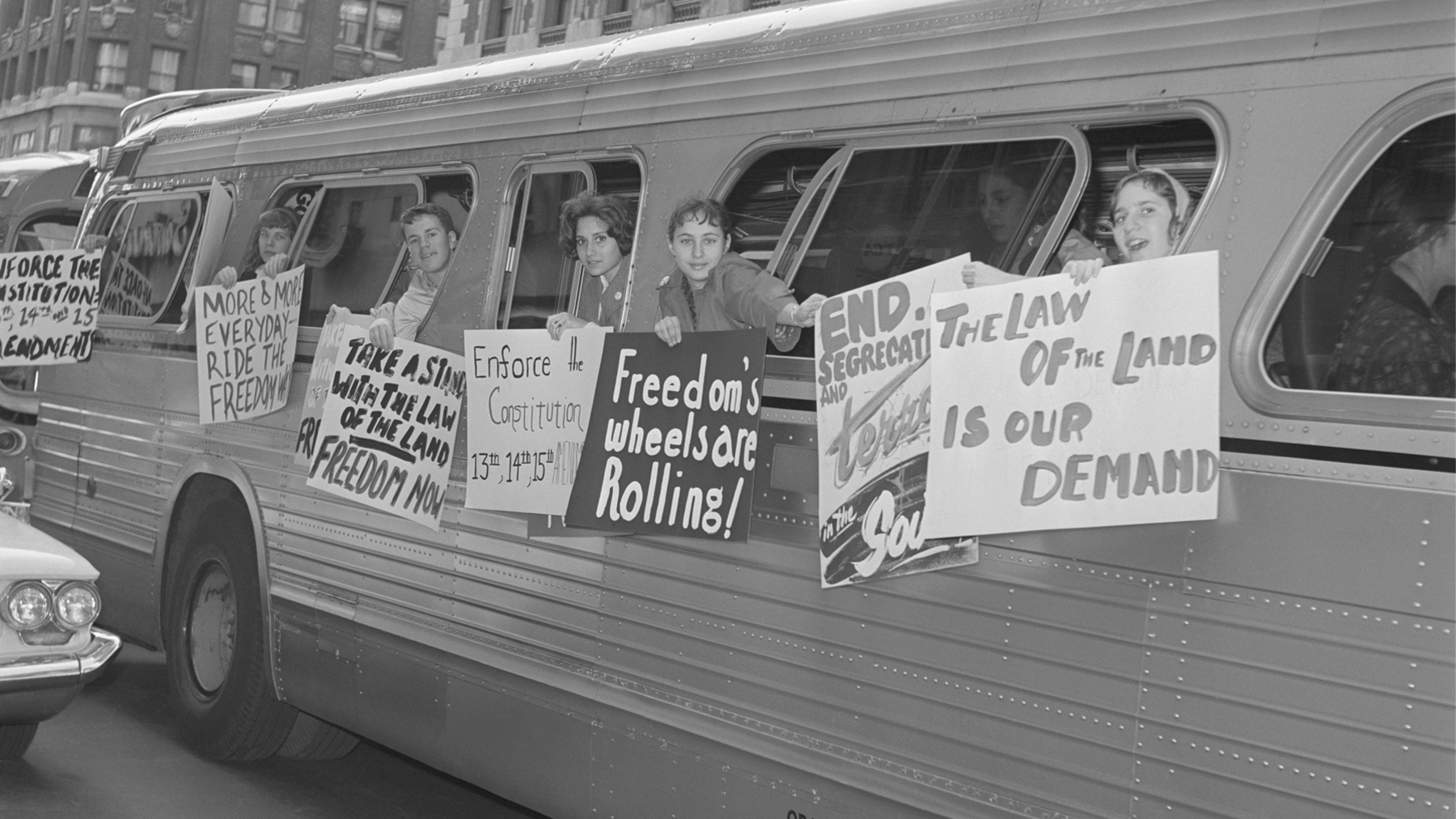

On May 4, 1961, seven Black and six white civil rights activists known as the Freedom Riders boarded a Greyhound bus in Washington, D.C., to travel through the Deep South to test the 1960 Supreme Court decision in Boynton v. Virginia – a ruling that found segregation of interstate transportation, including bus terminals, was unconstitutional.

Southern states ignored the Supreme Court decision, and the federal government failed to enforce it. Traveling from state to state, the Riders were met repeatedly with white supremacist violence as they demanded change. In some cases, law enforcement officers refused to intervene. And in some cities, the Riders were arrested for trespassing, violating local segregation laws or for other alleged offenses.

Fifty-nine years later, the courage of the Riders is enshrined in civil rights history – their legacy an example of the nonviolent resistance that defined the Civil Rights Movement and brought down the Jim Crow system of legalized segregation.

Shocking violence

When the Riders arrived at Rock Hill, South Carolina, on May 12, 1961, 21-year-old John Lewis, a founding member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and now a longtime member Congress, was assaulted when he and two others attempted to enter a whites-only waiting room. Two days later, after an enraged mob of roughly 200 white people in Anniston, Alabama, protested the Riders’ journey, one mob member hurled a bomb into the bus after another slashed its tires. The Riders narrowly escaped with their lives but were viciously beaten.

Meanwhile, a Trailways bus holding other Riders traveled on to Birmingham, Alabama, where the shocking violence against the Riders escalated. The group was attacked by another mob of white supremacists wielding metal pipes. Even though the Riders’ arrival had been announced and the city’s public safety commissioner knew of the violence awaiting them, no police were called in for protection.

Federal marshals step in

After widespread violence against the Riders, no bus driver would agree to transport the group until activist Diane Nash organized a group of 10 students to continue the rides from Nashville, Tennessee.

Former U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy negotiated with the governor of Alabama and bus companies to find a driver and protection for this new group. On May 20, 1961, the rides resumed, this time with a police escort.

But the violence hadn’t ceased. The police abandoned the bus before it arrived in Montgomery, Alabama, where again, a mob of white supremacists attacked the Riders, this time with clubs and baseball bats. Federal marshals were sent to the city to stop the violence.

The following night, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. led a church service in support of the Riders. More than 1,000 supporters attended but were threatened by a mob outside the church, prompting Kennedy to summon the marshals to use tear gas to disperse the white supremacists.

On May 24, 1961, the Riders departed Montgomery for Jackson, Mississippi, where hundreds of supporters greeted them. But the Riders who attempted to use whites-only facilities were arrested and taken to a maximum-security penitentiary.

During the hearings of those arrested, the judge refused to listen to the Riders and sentenced them to 30 days in jail. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People appealed their convictions at the Supreme Court. Their convictions were later reversed.

Hundreds of Freedom Riders continued the mission over the next several months. Finally, in the fall of 1961, the Interstate Commerce Commission issued regulations to officially prohibit segregation in interstate transit terminals.

Photo by Bettmann/Getty Images