Trailblazers who paved the way to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and those leading today.

After he was arrested and placed in solitary confinement for protesting segregation in April 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. penned his landmark Letter from Birmingham Jail, urging fellow clergy to support his work against racial injustice.

In May of that year, hundreds of peacefully demonstrating children were attacked in Birmingham, Alabama, with fire hoses, batons and menacing police dogs.

Just days later, the A.G. Gaston Motel – a Black-owned establishment where white business owners, city officials and civil rights leaders had reached a compromise to desegregate the city – was bombed, and four people suffered minor injuries.

The civil unrest in Birmingham captured the nation’s attention and prompted President John F. Kennedy to call in federal troops. Compelled by the images of peaceful protests met with brutal violence, Kennedy backed a comprehensive civil rights bill that was sent to Congress on June 19, 1963 – a week after civil rights activist Medgar Evers was assassinated in Mississippi.

That August, King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington. In September, the 16th Street Baptist Church was bombed, killing four young girls. These watershed events further galvanized public support for the civil rights bill, but Kennedy himself would not live to see it pass – he was assassinated on Nov. 22, 1963.

Kennedy’s civil rights bill fell into the hands of Lyndon B. Johnson, his vice president and successor.

Fifty-six years ago today, on July 2,1964, President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law. It ended segregation in public places. It also banned employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin. And it set the stage for the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which outlawed racial discrimination in voting.

“More than 100 years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 became law, the formerly enslaved abolitionist Frederick Douglass said, ‘If there is no struggle, there is no progress,’ and this sentiment was echoed in the sacrifices of those who suffered and laid down their lives for the civil rights we enjoy today,” said Tafeni English, director of the Civil Rights Memorial Center, which is operated by the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Alabama, and honors martyrs of the movement.

“The words of Frederick Douglass still ring true today in the clarion calls for racial justice following the recent murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, Sean Reed, Yassin Mohamed, Ahmaud Arbery and Rayshard Brooks,” English said. “The words of Frederick Douglass still ring true today in the ongoing fight against voter suppression across the South, and they ring true in the continued struggle for racial equality in our schools. As we celebrate the anniversary of the Civil Rights Act of 1964’s passage, we must remain vigilant in our fight for equality, as King said, ‘until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.’”

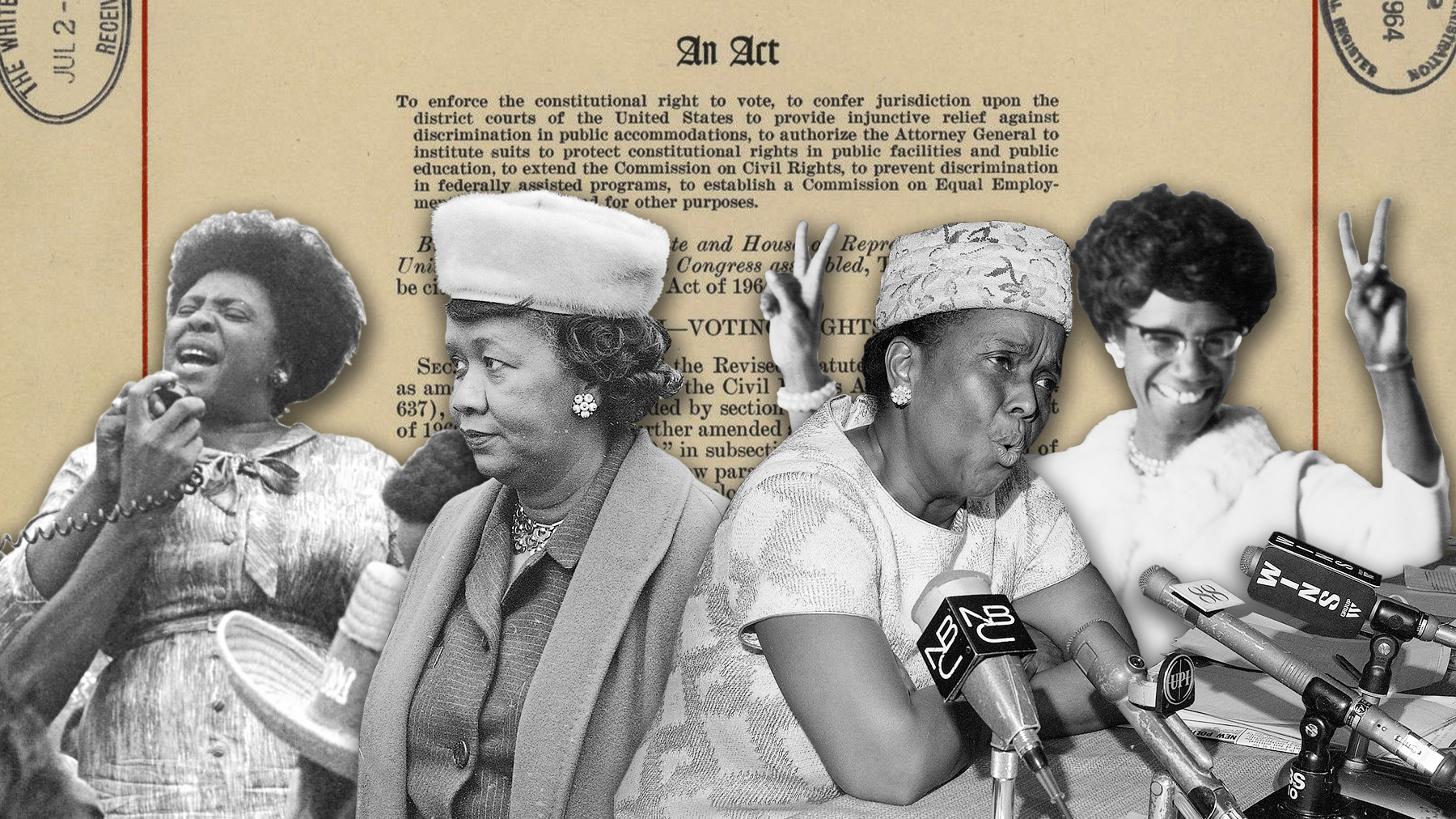

Women of the civil rights movement

The history of the fight for racial equality has often centered on men like King, Kennedy, Johnson and Evers. But far less attention has been paid to the women who made the civil rights movement possible.

They are women like Ella Baker, a former NAACP national director who worked to integrate schools in New York and improve the quality of education for Black children. Inspired by the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Baker co-founded the organization In Friendship to raise money for the civil rights movement in the South.

In conjunction with a group of Southern Black ministers, Baker helped form the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), with King as its first president and Baker as its director. She left the SCLC in 1960 to help organize the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which became one of the foremost advocates for human rights in the country. She also did much of the behind-the-scenes work for the protests that led to the Civil Rights Act’s passage.

Fannie Lou Hamer is another heroine of the era. Fighting against efforts to deny Black people the right to vote in her home state of Mississippi, she became an organizer for the SNCC. On Aug. 31, 1962, she led 17 volunteers to register to vote at the Indianola, Mississippi, courthouse. Instead of being allowed to vote, the group was forced to take a literacy test, harassed on their way home by police, and fined $100 on the bogus charge that their bus was too yellow.

After at last being allowed to register to vote, Hamer and other Black women were arrested in June 1963 for sitting in a “whites-only” restaurant in Charleston, South Carolina. At the jailhouse, several of them were brutally beaten. Hamer suffered lifelong injuries, including a blood clot in her eye and damage to her kidney and leg.

In 1964, soon after the Civil Rights Act was signed into law, Hamer co-founded the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), which challenged the local Democratic Party’s efforts to keep Black people from participating. Representing the MFDP, Hamer delivered a fiery speech to the convention with poignant descriptions of racial prejudice in the South.

While seeking reelection, Johnson – needing the support of Southern Democrats who opposed integration – tried to block attention to Hamer’s speech with a hastily called, televised press conference. But the move backfired: Hamer’s speech was shown in its entirety on primetime TV later that day. By 1968, Hamer had become a member of Mississippi’s first integrated delegation to the Democratic National Convention.

“Women like Ella Baker and Fannie Lou Hamer are often overlooked, but by recognizing their contributions we can more fully understand how the civil rights movement succeeded,” English said. “They largely operated behind the scenes, but their courage and conviction ensured that people like Martin Luther King Jr. and even President Johnson maintained their focus on racial justice.”

Another stalwart was Dorothy Height. After some time as a social worker, she joined the staff of the Harlem YWCA in 1937. One of her major accomplishments was integrating all of the YWCA’s centers in 1946. She later established the organization’s Center for Racial Justice.

Height became the president of the National Council of Negro Women in 1957, where she worked on various initiatives and campaigns with King, A. Philip Randolph, Roy Wilkins, Whitney Young, John Lewis and James Farmer, who were known as the “Big Six” of the civil rights movement.

Towards the end of the era in 1968, Shirley Chisholm became the first Black congresswoman. Four years later, she became the first Black candidate from a major party to make a bid for the U.S. presidency. Throughout her political career, she fought for educational opportunities and social justice.

Today, many Black women across the country are honoring Chisholm’s legacy by seeking – and holding – prominent positions of leadership.

Black Lives Matter

Washington, D.C., Mayor Muriel Bowser recently made headlines when, in the midst of a feud with President Trump over the use of federal force in the city, she had the “Black Lives Matter” slogan painted on the street in front of the White House in colossal yellow letters. The dispute followed the Trump administration’s decision to forcefully remove peaceful protesters so the president could have a photo op while holding a Bible in front of a historic church.

Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot, the first Black woman and the first lesbian elected to that post, has responded to recent calls for defunding the police by supporting reforms that would direct more resources to communities of color.

Several Black women are being evaluated as Joe Biden’s potential running mate, a move that could put one of them a heartbeat away from the presidency. Among them are Karen Bass, chairwoman of the Congressional Black Caucus; U.S. Sen. Kamala Harris of California; former Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams, U.S. Rep. Val Demings of Florida, and Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms, who has become a leading voice in the national debate over race and policing.

And the current nationwide struggle against police brutality was inspired by three Black women, Patrisse Khan-Cullors, Alicia Garza and Opal Tometi, who co-founded the Black Lives Matter movement following the 2012 killing of Trayvon Martin.

“Black women were the backbone of the movement that produced the Civil Rights Act of 1964,” English said. “After years of continued oppression, the march for justice has reached another historic inflection point, and Black women are once again leading the way.”

Illustration by Sunny Paulk

Credit Khalid Naji-Allah/AP

Credit Bettmann/Getty Images