Looming over the heart of downtown, a statue of Confederate Brigadier General J.J. Alfred A. Mouton stands austerely on its pedestal, his arms folded stiffly across his chest, his hardened expression etched in stone and locked on the city of Lafayette, Louisiana, as if he’s still at war.

The memorial to Mouton has loomed over the grounds of what used to be city hall for nearly a century in this Deep South parish, where, in the days before the Civil War, the number of enslaved people who were forced to work on the sugarcane plantations nearly equaled the population of free people.

Now, in a moment of national reckoning over the painful reality of Confederate memorials, Mouton’s symbolic reign might be finally coming to an end.

After a four-year battle, community activists are pinning their hopes on litigation that could result in an order allowing city officials to take down the statue of Mouton, ridding Lafayette of its public display of white supremacy. A judge is expected to rule on the issue following a Jan. 11 hearing.

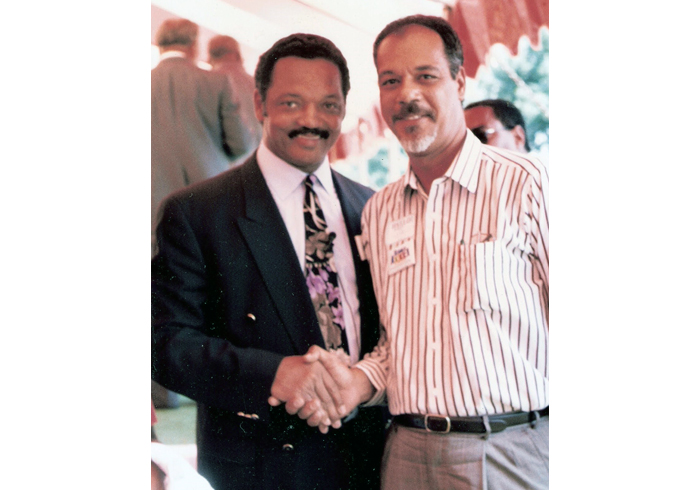

That moment can’t come soon enough for Fred Prejean, who has long been a leader in the movement to educate local residents and overcome legal roadblocks to the statue’s removal. Like other activists engaged in similar battles across the South, he and his allies have met fierce resistance in Lafayette, where about a third of the 135,000 residents are Black.

“There are people who have a cultural attachment to Alfred Mouton,” Prejean said. “They don’t want to see the statue moved. They say, ‘Hey, this guy represents part of our heritage.’ But the heritage he represents is of a slave master – a kind of person who would lead vigilantes. They don’t think of that when they talk about their heritage.”

A ‘bad guy’

Prejean, 74, has felt Mouton’s foreboding presence since, as a child in the 1950s, he would go with his mother to pay the utility bill at city hall. He recalls asking about the statue, but his mother wouldn’t say much, only that Mouton was a “bad guy.”

As he grew older, Prejean realized why his mother didn’t say more. Though change was on the horizon, the oppressive codes of Jim Crow segregation in the Deep South were still in full force, and it was dangerous to speak ill of white people.

As an adult, Prejean became involved in the civil rights movement. He was inspired by the late Congressman John Lewis, a longtime family acquaintance, and by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1963 “I Have A Dream” speech, which he witnessed in Washington, D.C. Later, he worked to organize cooperatively owned businesses to encourage economic development in the town’s Black community.

Through his work and having lived in Lafayette his entire life, Prejean knew that many Black residents felt the same way his mother did about the Mouton statue.

So in early 2016, he began doing something about it.

The moment had arrived. Less than a year before, on June 15, 2015, a young white supremacist had murdered nine Black worshippers during a prayer meeting at the iconic “Mother Emanuel” AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina. Afterward, the emergence of social media photos of the attacker with a Confederate flag sparked a nationwide movement to remove Confederate symbols from public spaces.

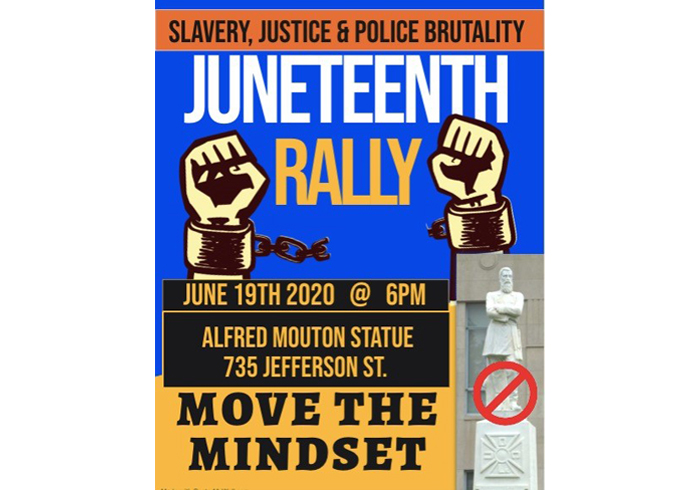

In May 2016, Prejean and fellow community members formed Move the Mindset (MTM) – a nonprofit organization committed to addressing discrimination and other social injustices.

Above all, its mission was to educate and advocate for the truth. It’s first target: Mouton.

“Lafayette now had to face up to its history,” said Greg Davis, 65, a retired public assembly facility manager and MTM founding member. “It had to decide what it wanted to be going forward and how it wanted to be remembered, especially the city council. There was massive momentum [for Lafayette] to admit to its history of white supremacy and to declare that it needed to end, and that all of this [Confederate] symbolism needed to be destroyed or removed.”

A false history

Educating the people of Lafayette was an important first step. And to do that, Prejean and others had to conduct their own research.

They knew, of course, about the region’s white supremacist history, its early economy based on brutal sugarcane plantations that flourished with slave labor. Mouton was very much a part of that history – a member of the city’s founding family and as close to royalty as it gets in Lafayette Parish. His father, who became a Louisiana governor, was born into a wealthy, plantation-owning Acadian family (in what later became Lafayette Parish) in 1804, just a year after Napoleon sold the territory to the United States.

Mouton, a West Point graduate, was himself a sugarcane grower in the parish and also the leader of the Lafayette Vigilante Committee. In 1864, he was killed while leading a Confederate cavalry charge against Union troops in the Battle of Mansfield.

But it wasn’t just the reality of who Mouton was – it was also about what his statue represents today. It was erected in 1922 by the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) as part of a decades-long propaganda campaign aimed at keeping alive the myth of the “lost cause,” a false version of history that glorifies the Confederacy and its leaders as fighting for something other than to preserve white supremacy and the enslavement of millions of Black people. Since the 1890s, the UDC has been responsible for erecting more than 700 memorials honoring Confederate soldiers across the country.

In its 2016 Whose Heritage? report, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) found that most public symbols of the Confederacy were put in place during two distinct periods: first, during the early days of Jim Crow, when millions of Americans belonged to the Ku Klux Klan, and then during the white supremacist backlash to the civil rights movement in the 1950s and early 1960s. The SPLC identified more than 1,700 monuments and other Confederate symbols nationwide, many of them occupying prominent positions in towns and cities across the Deep South. As of Oct. 15, the SPLC has documented 171 such symbols that had been removed, renamed or relocated since the Charleston attack.

Dr. Rick Swanson, a professor of political science at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette and an expert on civil rights law, said Lafayette’s history has been thoroughly mythologized – or “whitewashed” – much like that of the wider South. After spending nearly four years combing through old census data, election reports, faded newspapers dating back to the 1800s and official archives, he found a “gaping hole” in the widely accepted, sanitized version of the city’s past.

“I wasn’t surprised by the general theme of oppression, I was surprised by how bad it was,” Swanson said. “Up through the late 1800s, racism was as bad or worse in Lafayette parish than it was [anywhere in] the South. Forty-nine percent of the population was enslaved, and exactly half of the white households owned slaves. There was such widespread, systematic terrorism. I wasn’t surprised why [the city] hid it.”

When the Mouton statue was erected, Swanson said, Black people weren’t allowed to vote. There were no Black elected officials, no Black police officers, no Black lawyers and only a handful of Black-owned businesses. To this day, residential patterns still reflect a 1923 zoning ordinance that required Black people to live only in a certain part of town.

“You need to tell the whole history,” said Patricia Colbert, a 76-year-old retired educator and MTM member. “Show the entire history, what happened to Blacks, what happened to whites, everything. Show all of that, not just the Confederacy.”

Changing the mindset

To win over local residents, MTM mounted a multifaceted campaign that included panel discussions, documentary film screenings, appeals to the city council, presentations at the public library and peaceful demonstrations at the statue itself.

In the beginning, about half the speakers at a city council meeting, all white, opposed removing the statue, said Swanson, who is white and supports the movement.

“Several older white speakers said [people] were ‘just causing trouble’ and that ‘we’ve never had a race problem,’” Swanson said. “But we still have mostly segregated schools and segregated neighborhoods. Black incomes are still less, and Black wealth is still less.”

Many white people in the city clung to the very narrative promoted by Mouton’s statue and groups like the UDC.

“They know the ‘lost cause,’” Swanson said. “They say the Confederacy is not about slavery or white supremacy. And then there are others who are apathetic. [A]nd then others don’t care if [Mouton] fought for white supremacy.”

But, over time, many people began to rethink their attachment to the statue.

“About six months ago, [we] sat at the base of the statue every day for about a week,” said Colbert. “We prayed and read, so it attracted a lot of attention. People asked us, ‘Why are you doing this? What’s it all about?’”

Finally, there came a significant breakthrough last summer.

In May, the death of George Floyd at the hands of white police officers in Minneapolis sparked mass demonstrations for racial justice across the country. Like the 2015 attack on the church in Charleston, the watershed moment fueled the push to remove Confederate symbols from public spaces. As of Oct. 15, the SPLC documented the removal or renaming of 102 such symbols since Floyd’s death.

On June 19 – four weeks after Floyd’s death – Prejean spoke to a crowd at the Mouton statue. It was Juneteenth. “Deaths by racial violence have often served as a catalyst for demands for justice,” he said. “Yet this time feels different. … A tipping point has been reached. We have united in solidarity to say enough is enough. The time has come for deep change below the surface. … This statue must come down.”

Lafayette Mayor-President Josh Guillory announced his support for the removal on July 1 and, after a nine-hour meeting three weeks later, the city council unanimously endorsed it during a 2 a.m. vote.

Still, the movement faced one more hurdle – a 40-year-old court order.

The order has been in place since 1980, when the city wanted to relocate the statue to a new city hall. The UDC filed suit to stop the move, and a settlement was enshrined in a permanent injunction that locked Mouton in place.

By the time city officials agreed to remove the monument this past summer, Prejean together with 15 Lafayette citizens had already filed a court motion seeking to lift the injunction, claiming the UDC did not have legal standing to sue the city because it had donated the statue. Now, absent any appeals, a final court ruling in January seems likely.

Reconciliation

The success of MTM’s campaign, though it took four years, has taken founding member Davis – who is old enough to remember separate water fountains for Black people – by surprise.

“I told Fred [Prejean] that we will go to our graves, and this monument will remain standing,” Davis said. “I thought there was going to have to be an emergence of a new generation. Louisiana is a very red state, and Lafayette seems to be the center of it all. But there has been some movement of the mind.”

Prejean hopes the city will consider moving the Mouton statue to a museum, so that people can learn the truth of the Confederacy and the centuries-long oppression of Black people that continues to this day. Davis and other MTM members agree.

“The history needs to be told, but it need not be a reconstructed history … and we certainly should not be using public places and public dollars to promote a false history,” Davis said.

When and if the statue is taken down, reconciliation is the next, most pivotal step toward erasing the lasting effects of Jim Crow and putting the city on a path toward racial equity.

“We were brave enough to confront the fears that people were reluctant to talk about or express,” Prejean said. “We want to use the statue as a teaching tool. That’s the reason we want it preserved. That opens the doors to reconciliation. That is what we hope will follow. Then we’ll be able to feel some sense of peace and go to our citizens and say the truth has prevailed.”

Learn more about Move the Mindset and support its mission here.

Image at top by Collin Richie.