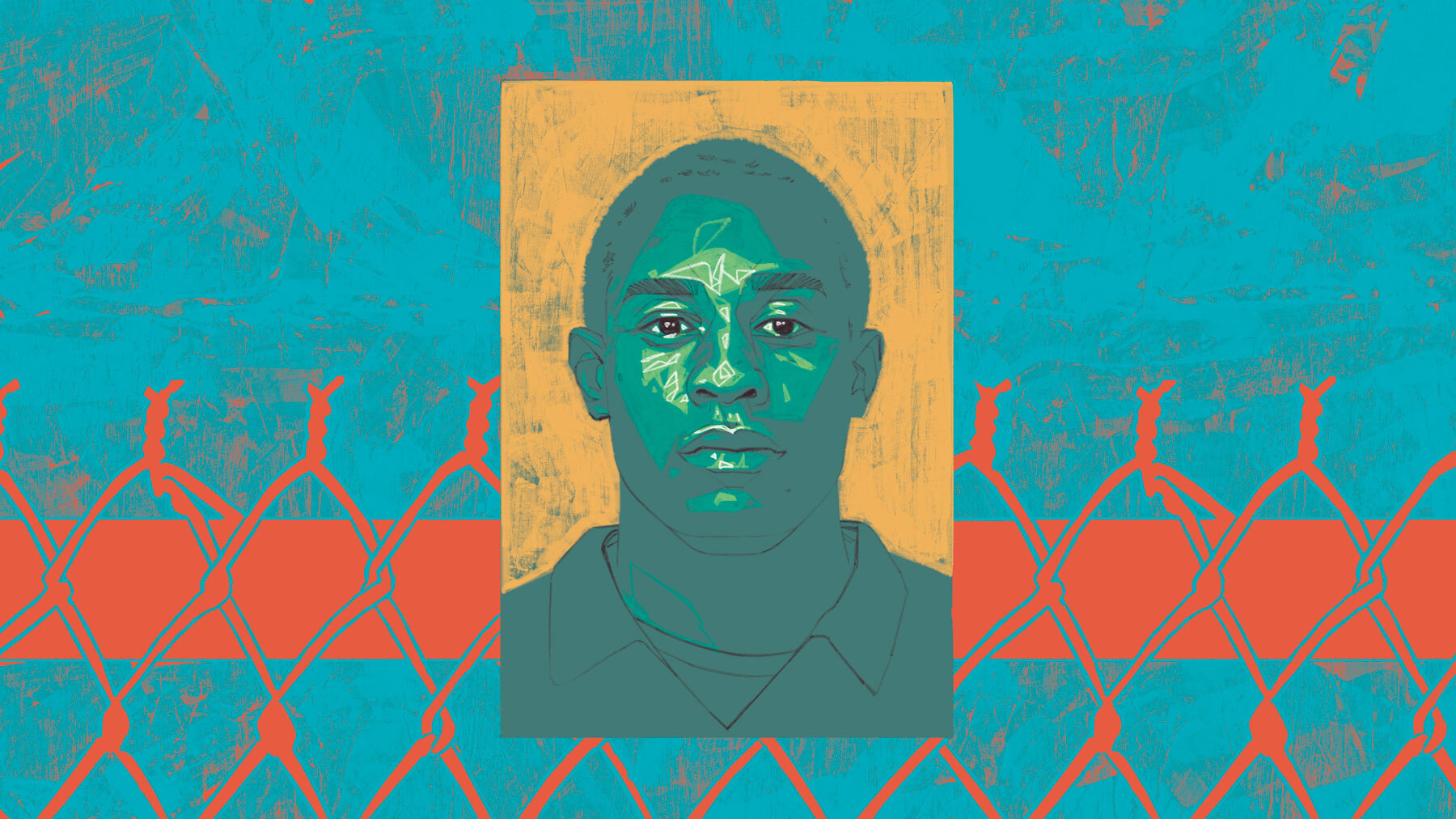

Gaaron Bethel is trapped in the revolving door of Alabama’s criminal justice system.

At 53, he is incarcerated at Childersburg Work Release, a minimum-security facility in Alpine, Alabama. He’s serving the remainder of a 35-year enhanced sentence for one count of burglary of an unoccupied store from an incident in 1994 where nothing was stolen. The rest of the sentence stems from two counts of illegal possession of a credit card from 1996, charges to which he pleaded innocent.

But these charges aren’t even the reason Bethel is currently behind bars. It was a parole violation that sent him back after being granted parole in October 2017.

His experience is an example of how even when someone is fortunate enough to be paroled in a state with a low parole grant rate, they can quickly be sent back to Alabama’s dangerously overcrowded prisons over small violations. In Bethel’s case, returning to his small town where it seems residents and police only see him as someone who has been to prison made starting over a challenge and ultimately led to his return to prison, Bethel and his older sister said.

“I paid my fees every month and I reported every month,” Bethel told the Southern Poverty Law Center in late November. “I even passed all the drug tests, I don’t do drugs anyway, but I took all the tests they wanted me to. I did everything the parole board wanted me to do upon my release, and then I get a violation.”

In May 2018, not even a year after being released from prison, Bethel was arrested in Georgiana, his small central Alabama hometown. The charge was for criminal surveillance, a misdemeanor, for allegedly looking into a resident’s window. Yet, to this day a case has never been tried, and Bethel has never been convicted of any crime related to the alleged incident. According to the Georgiana Municipal Court clerk, there is the possibility the case may be dismissed. A judge has the option to dismiss the case before it’s even tried, particularly since the case has already sparked revocation of Bethel’s parole and returned him to prison.

A small town’s memory

In Georgiana, a town of roughly 1,600 people, residents don’t forget when a member of the community goes to prison – even if they don’t remember the charge. For Bethel, it meant that people were too eager to call the police on him again, according to his sister.

“The only thing I know is that [Bethel] was walking down the road,” said Brenda Scott, his older sister and a school teacher in Georgiana. “It could have been said at any given time, if he was seen walking down the road and someone said, ‘Hey he’s peeping in my window,’ then that’s it around Georgiana.

“That’s all he needed was someone to call and report it. He didn’t even need to come near the house, he could’ve been on the other side of the street. But because people saw he was walking, that was a problem, all because he didn’t have a car or something.”

In June 2018, a month after Bethel’s initial arrest, the “peeping” allegation resulted in him charged as a parole violator. He was held in Butler County Jail until August when he was transferred back into the custody of Alabama’s Department of Corrections. He has remained there since.

Scott says she has cautioned her brother not to come back to Georgiana the next time he’s released – it appears too risky because of police and community scrutiny. Although their upbringing taught them not to question the court system, Scott’s years as a school teacher have allowed her to see other young men in Georgiana become entangled in the criminal justice system like her brother.

“It’s sort of like they’re getting stuck,” she said. “Certain people get those charges, they don’t have a problem with it” and can successfully restart their lives. But she added: “Certain Black boys get arrested with the same charges, and it’s messing them up for the rest of their lives.”

This past August, Bethel was denied parole.

Among the reasons the parole board indicated on his denial paperwork: “No reasonable effort made to complete rehabilitative programs while incarcerated, negative input from stakeholders (victim, family of victim, or law enforcement), multiple parole or other community-based supervision revocations.”

However, there’s evidence Bethel completed several programs during the years he’s been incarcerated, including the Substance Abuse Program and faith-based programs. He also received his GED diploma. Despite these efforts, Bethel has fallen into a cycle of minor parole and probation violations over the past several years that’s pulled him back into the state’s prison system again and again.

“When you’re in a situation like that, you’re basically totally helpless,” Bethel said.

‘You were supposed to trust them’

Bethel was born in Georgiana, a town in Butler County within Alabama’s Black Belt region. He was the youngest boy of eight children. Bethel said his father was a natural business owner who worked in lawn care and the logging industry during his early years. Later, his father became a licensed minister, as did his mother.

“My dad is the one who taught me how to work,” said Bethel, who wants to take courses online in business administration whenever he’s released from prison. “He taught me how to get out there and make money.”

Bethel first encountered Alabama’s criminal justice system in his early 20s, when he was just getting started in life.

He was put on probation for a theft charge in Montgomery in 1992. Court records state he was seen wearing a friend’s clothing after it was allegedly stolen at a laundromat. The real trouble, however, started when he was picked up in Butler County for a burglary charge in 1994.

According to the indictment, Bethel committed burglary in the third degree or was “unlawfully in a building,” a local grocery store in Georgiana, “with the intent to commit a crime.” Nothing was actually stolen. Still, Bethel, though initially pleading not guilty, took a guilty plea in 1995 and received a 15-year split sentence with two years to serve for the charge then three years of probation.

Bethel told the SPLC he never set foot in the store, and said he was a victim of police brutality after one of the arresting officers hit him in the head several times as he was arrested on a nearby street. He filed a civil lawsuit against the Georgiana Police Department in 2002 over the incident, but the officers named in the suit denied his claim. The statute of limitations had expired, so the case was ultimately dismissed.

“My parents … didn’t know to question anything,” said Scott, reflecting on their upbringing in Georgiana and her brother’s early cases. “The police were the best in the world, and you were supposed to be able to trust them to do the right thing.”

Today, however, her brother’s experience makes such trust in the criminal justice system difficult, if not impossible.

In October 1996, when Bethel was released on probation, he was arrested again by Georgiana police within a week for allegedly breaking into vehicles. He wasn’t charged for breaking into the vehicles, but he was eventually charged with two counts of illegal possession of a credit card that was taken from one of the cars.

This time Bethel maintained his innocence and took the case to trial, but was convicted in 1998 as a habitual offender because of his two prior felony charges. He was sentenced to 20 years for each count to run concurrently. Because he was also on probation at the time of the arrest, his probation was revoked and the original 15-year sentence for the 1995 burglary charge was applied, resulting in a 35-year sentence.

Bethel, adamant about his innocence and the unfair nature of the excessive sentence, has filed almost a dozen motions for post-conviction relief pro se, or on his own behalf, since 1998.

One of his motions holds a letter from the alleged victim in the credit card case that notes, “I was told my purse was found while the person was attempting to burn it. I don’t believe the police mentioned a name at the time. Only after I was summoned, did I see your name. And if you will read the transcripts of my testimony at the trial, or if you can remember, I never once pointed you out or said that I saw you do it. So I can not falsely accuse you, if I never accused you. I don’t know you, I don’t have anything against you, nor would I gain anything by your incarceration. … I will pray that your life will get back on track.”

One of hundreds harshly punished for violations

Still, Bethel’s motions, and opportunities for freedom, have been denied or taken away for minor missteps when he has been released over the past two decades.

Bethel was also paroled once in 2006 but, according to Scott, received a violation for sleeping over at a woman’s home he was seeing at the time while living at his mother’s house.

“His address was my mom’s and he met a young lady and would go to her place when he got off work. But they told him if he moved somewhere else he had to let his parole officer know. Well he didn’t actually move anywhere else, he just spent the night there,” Scott said. “He was being returned [to prison] on nothing. I don’t know if there were any charges each time he was returned. It was just the fact the police were called on him.”

Bethel was back in custody of the Alabama Department of Corrections in 2007.

“We have no choice but to just let them do it,” Bethel said about parole violations. “What we say ain’t gonna change nothing.”

Unfortunately, Bethel’s back and forth with the parole system is not unique.

Between May of this year, when Alabama’s parole board returned from a hiatus due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and Dec. 3, only 564 people were granted parole out of 2,669 hearings. During these parole board meetings, almost as many people – 557 – had their parole revoked, and 923 more were declared delinquent, meaning they’ve received a violation, opening the possibility of revocation at a future parole court hearing.

For Bethel, with his most recent parole denial, he most likely won’t be released until 2022 when his sentence ends. Since he’s been incarcerated his father has died and he’s lost a brother. His mother, now in her 80s, has dementia. According to his sister, the last time Bethel was home in 2017, his mother hardly recognized him due to her condition.

But Bethel stays focused on fighting his cases to this day, and starting and maintaining a business, maybe a lawn care company like his father, whenever he’s out of custody.

“I just take it one day at a time, and when I see negatives I try to veer the opposite direction,” he said. “I try to keep myself motivated, I never say, ‘I cannot’ because I know I can. It’s what keeps me going every single day.”

Read more about the Freedom Denied series here.

Illustration by Ryan Simpson