Check for updates: This story will be updated throughout the day with reports from the Southern Poverty Law Center following the events marking one year since the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol.

Alabama democracy advocates gather at site of famous King speech after Selma march

By Liz Vinson

5:30 p.m.

As President Joe Biden and others in Washington, D.C., condemned those who encouraged and participated in the Jan. 6 insurrection, pro-democracy advocates across the country staged vigils to promote voting rights and remember those who died and were injured during the assault on the U.S. Capitol.

In Montgomery, Alabama, a small but energized crowd gathered at the state Capitol, where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “How Long, Not Long” speech on March 25, 1965, at the culmination of the Selma-to-Montgomery voting rights march.

Demonstrators held signs reading “Fight poverty, not the poor” and “Votes not violence,” even as rain threatened to cancel the event.

“Over the course of the last year, we’ve seen further assaults on voting rights and elections,” said Kathleen Kirkpatrick, an organizer of the vigil hosted by the Hometown Organizing Project. “We want to preserve democracy and promote calling on elected officials and the White House to protect [voting rights].”

Mike Kane, a resident of Richmond, Virginia, who was in Montgomery visiting famous civil rights sites, said he attended the vigil because it was not only about protecting voting rights but also to recall how the insurrection represented an ongoing attack on democracy.

“Until we defend democracy with voting rights, the insurrection will start to grow and become bolder,” Kane said. “I think what happened last year was a tragic practice session. For some of these militias, I believe they will be back and try harder to end democracy.”

The event concluded with a prayer by the Rev. Carolyn Foster of Greater Birmingham Ministries, asking God to keep our democracy intact and to promote the voting rights of people of color, elderly people and people with disabilities.

As demonstrators departed, many left chanting, “This is what democracy looks like.”

The scene in D.C.

Updated 8:20 p.m.

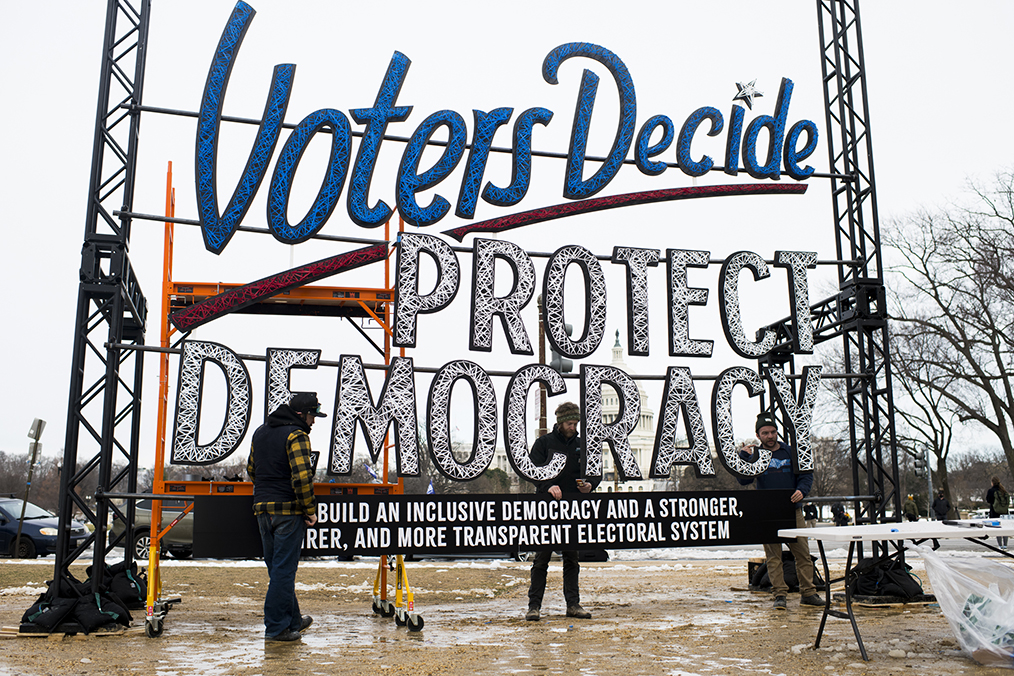

Photographer Pete Kiehart documents the events in Washington, D.C., on the one-year anniversary of the January 6 insurrection.

The battle for social justice and voting rights continues in the shadow of Jan. 6

by Dwayne Fatherree

When an armed mob of then-President Donald Trump’s supporters attacked the U.S. Capitol to prevent the transfer of power to then-President-elect Joe Biden, Susan Corke had not yet assumed her new role as director of the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Intelligence Project.

“I started at the SPLC on Jan. 19,” Corke said. “I was sitting at home preparing for the job and watching the horror of that day unfold. I knew that this changed everything.”

Like most Americans that day, she was also aware that the damage done was more than physical.

“It created this existential crisis for our democracy that we would be dealing with, and fighting against,” Corke said. “And the danger to our democracy has never been more grave.”

That sense of gravity has not diminished since the failed coup attempt, the violent insurrection that left five dead and more than 140 police officers injured. Time has also failed to bring an end to the efforts to subvert our democracy, with more than 400 state legislative proposals to restrict voting rights and, in some cases, allow partisan politicians to overturn election results.

Invariably these actions seek to restrict access to the polls for voters of color. Additionally, the once-a-decade reapportionment process has seen new voting district maps drawn across the South that underrepresent Black and Brown voters, ensuring that Congress, legislatures and local governmental bodies will be far less likely to match the demographic makeup of their constituencies.

Caren Short, a senior supervising attorney with the SPLC’s Voting Rights Practice Group, said serving as a watchdog during the current push to dilute the political power of Black and Brown residents is a top priority as redistricting maps make their way through state legislatures and local governments.

“As 2022 begins, we’re focusing on one of the foundations of democracy: redistricting,” Short said. “We are working to ensure that everyone has fair and transparent representation in their cities, counties, state and federal representatives.”

Corke and Short are not alone.

“Jan. 6 has had a lasting impact for so many of us fighting for democracy and racial justice,” said Margaret Huang, president and CEO of the SPLC. “It clarified the larger societal schism in our country. We witnessed that day, and for the last several months, that a significant number of Americans believe that the use of force was justified in overturning the 2020 elections.”

As the nation marks the first year in a post-Jan. 6 world, the key question raised that day remains: Can the American experiment in democracy survive an assault from within?

“Emotionally, it has sparked fear and anxiety for many Americans,” Huang said. “For others, it has provoked anger and resentment. We seem to be at a pivotal crossroads where the future identity of our nation is at stake, and that challenges everyone, regardless of ideology.”

‘I became angry’

For Lecia Brooks, chief of staff at the SPLC, the sight of the Capitol being desecrated is still fresh in her mind.

“One year later, I can vividly recall the feelings I had watching the takeover of the Capitol building on Jan. 6,” Brooks said. “It was a mix of shock, foreboding.”

The contrast between the extreme military presence during the protests outside the White House in the wake of George Floyd’s death the previous summer and the comparatively deferential treatment given to the Jan. 6 insurrectionists was not lost on Brooks.

“As throngs of angry, mostly white Trump supporters forced their way into the building, I became angry,” she said. “I kept thinking, this would not happen if these were Black folks. They would have been stopped long before breaching the door. Seeing mobs of people carrying Confederate flags and donning antisemitic messages mixed with Trump signs and the American flag was terrifying. I kept waiting for them to be stopped.”

But they weren’t, not for hours. After swarming the Capitol Police, the rioters took to the halls of Congress, rifling through offices and desks as they sought members of Congress who had already been evacuated from the building. Finally, Trump issued a video expressing his love for the invaders. He told them to go home, with no mention of arrest or repercussions. And they did.

“More disconcerting was the way in which some law enforcement officers charged with protecting and defending the Capitol were accommodating the rioters,” Brooks said. “I’ve never seen anything like it. I’m still haunted by what I witnessed on the livestream. I’m even more angry that, a year later, the coordinated incursion on our democracy has been minimized. I know it can happen again. Next time, they may be successful. I truly believe our democracy is at great risk of being overthrown.”

It is the specter of a next attempt to subvert democracy that keeps Eric K. Ward, executive director of the Western States Center and a senior fellow with the SPLC, moving forward. A former punk rocker from Los Angeles, Ward has seen violence at the hands of white nationalists as well as the police who were supposed to protect the public.

“In the 1980s, it was volatile,” Ward said. “The counterculture in L.A. was super-volatile. There were neo-Nazis who just came to beat up on people. There were police who would be waiting for us outside to beat up on anyone.”

Those intense moments served as a crucible, forming Ward’s desire to fight for justice. And, although not a direct correlation, he said he can see the same divide, the same divisions facing youth today.

“In this moment, the question isn’t going to be called on democracy,” Ward said. “The question has already been called. The white nationalist movement and its coalition is declaring that democracy has no place in the trajectory of America. We have to show that it does work, and it is true. There is no neutral position on that, either. You participate in democracy, or you are handing America over to the white nationalist movement at this point.”

Finding a cure

Corke points to the work of the SPLC’s Intelligence Project as one way to stem the growth of the extremism that is infecting American politics. The group of investigators and analysts monitors hate and extremism – the groups, the movements, the extremist and white supremacist leaders – exposing them to the public and, in doing so, holding them accountable.

“We also are looking to better understand hate and extremism as a danger to democracy and inform Congress, the administration, the media and the American people on the digital and financial landscapes of hate,” Corke said. “So, we’re providing a fuller picture of what is happening, and providing some actionable recommendations for what can be done.”

One aspect of that effort is to focus on preventing hate before it becomes a hate crime. The SPLC’s partnership with the Polarization and Extremism Research and Innovation Lab (PERIL) at American University seeks to identify those who might be vulnerable to radicalization “farther upstream” and put effective resources in the hands of teachers, parents and other caregivers who can head off the radicalization process.

The research so far has found that parents or teachers who spent only seven minutes reading the SPLC/PERIL guide were more than 80% more likely to recognize the signs of radicalization. Additionally, more than 80% felt they were prepared to intervene effectively with their child or student.

“The SPLC is seeking to address these conflicts and tensions with practical solutions,” Huang said. “First, we create educational resources that help people understand these threats to our democracy and the importance of standing up in its defense. Second, we are monitoring and disseminating information about the actors who threaten communities of color, the LGBTQ community and others by tracking hate and extremist groups. We are working with partners to create tools that help young people, their families and communities prevent radicalization. And, of course, we are suing state legislatures that are seeking to limit voting rights and to discourage civic engagement. The SPLC is deeply committed to protecting the institutions of our democracy and to strengthening the practices that enable everyone to participate and vote.”

Seeking justice

The fight for accountability in the wake of the attempted coup of Jan. 6 is ongoing. More than 700 people have been criminally charged, with about 50 of those cases already adjudicated.

The biggest legal splash thus far, however, is not a criminal case. In addition to handling those criminal prosecutions, Washington, D.C. Attorney General Karl Racine’s office filed a civil suit last month naming the Proud Boys and the Oath Keepers, as well as more than 30 individuals, as defendants. The suit is seeking unspecified damages for the harm, destruction and death during and after the Jan. 6 attack.

The lawsuit is in keeping with Racine’s initiative as president of the National Association of Attorneys General, where he has focused on the fight against hate and extremist groups.

“In leading up to my presidency, I focused on what I thought was the single most important issue in the United States of America,” Racine said. “And that’s the actions of domestic terrorists and those who would support them, all around hate. So the initiative certainly informed me a lot about what needed to be done in order to deter hateful groups from feeling as though they could act in any unlawful and violent way that they chose.”

Racine said that criminal charges would be filed where appropriate, but he discovered over the years that the most efficient way to shut down an organization that espouses hate is to hit it in the pocketbook. Previously, the D.C. police chief testified before Congress that the physical damage from the attack would cost about $8.8 million – not counting injuries, deaths or other trauma inflicted on that day. Beyond that, holding the groups identified as leading the most violent portions of the failed coup accountable is Racine’s first and largest concern.

“Subsequent to the Jan. 6 event, three police officers died by suicide and dozens more are suffering significant mental health trauma,” he said. “(That includes) former Metropolitan Police Officer Michael Fanone, who bravely fought off the insurrectionists even as they were yelling, ‘Take his own gun and shoot him.’ They beat him with flagpoles. They stun-gunned him with a Taser or some other shock gun. He had a heart attack and a concussion. He is a father of three. And can I tell you in 2016 he voted for Donald Trump, as if that matters.

“He was fighting for democracy that day,” Racine said. “That’s what this lawsuit is all about – our freedom.”

Faith

The solutions to these monumental challenges lie with each and every citizen, Ward said.

“I think I would first make sure I belong to an organization in my community,” Ward said. “It doesn’t have to be a political organization. But within that organization you have to bring this topic, the insurgency, up for conversation. Maybe this article is the article you use to have that discussion. And that organization you belong to has to do one thing. It doesn’t have to do everything right, but it has to figure out one thing it can do.”

On a more basic level, Ward said that one of the strongest defenses against extremist thought is community.

“You don’t have to have political conversations with your neighbors, but get to know them and get to know your block,” Ward said, “One of the ways that these types of authoritarian insurgencies make breakthroughs is they convince us that we are divided, right? They use ideology, because it’s easy to show ideological divide in any situation. But what we forget is, beyond our ideology, it’s likely that most of our values are very much aligned and we don’t know that.”

The third key Ward offered is to persevere.

“We have to prepare ourselves mentally for a hard time, but we can’t get into the despair. We’re going to see lots of highs and lows in this period, just like in the midst of the civil rights movement. We think about the civil rights movement as a period of moral clarity and high energy, but it was a very hard period in American history. This will be, too. So I guess the third thing I’ll come back to is that despair is the only unforgivable sin.”

Brooks summed up her approach to fighting the current social and political battles in two points.

“Professionally, I’m working with my colleagues at the SPLC to ensure that the insurrectionists are held accountable and that the record of what really happened is not lost to a disinformation and denial campaign being pushed out by the former president and his supporters,” Brooks said.

“Personally, I pray.”

Photo at top: Barricades surround the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., one year following the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection. (Credit: Pete Kiehart)

More on Jan. 6

To read SPLC’s complete coverage of the January 6 insurrection, visit The Long Path to Insurrection.