The afternoon was warm and sunny on April 7, 1964, when Joanne Klunder took her two young children to the Cleveland zoo. Her husband, the Rev. Bruce Klunder, set out in the opposite direction, to protest an evil that he and his wife deeply opposed – school segregation.

Before the day was out the white minister, just 26, would be dead. His body, which he had thrown down behind a bulldozer wielded to build a school explicitly designed to keep Black and white children from taking classes together, would be crushed. Joanne Klunder would be a widow. Her children, Janice, 6, and Douglas, 3, would be fatherless. And in the days and months that followed, the path of the civil rights movement in Cleveland and beyond would be forever changed.

As grief and rage over Klunder’s death spread, first locally and then nationally, the snuffing out of a young activist’s life would help galvanize a shift in the civil rights movement from trying to sway hearts through nonviolent protest to growing Black power and transforming racist systems through political action.

This weekend, the legacy of Bruce Klunder’s death, along with the life of activism, sacrifice and teaching that his widow – who changed her name to Joanne Klunder Hardy when she remarried – has carried on in the six decades since, are being honored anew by the Southern Poverty Law Center. At a private ceremony April 22, a wreath will be laid in Bruce Klunder’s memory at the Civil Rights Memorial across from the SPLC’s headquarters in Montgomery, Alabama.

At the same time, the SPLC will announce the establishment of the Klunder Social Justice Fellowship, a new initiative funded by Janice Klunder and her husband, Kollol Pal, to advance systemic change and justice through engagement in schools and community organizations.

“The movement that the Klunders led in Cleveland was not about accommodation, it was not about assimilation, it was about radical change,” said Jalaya Liles Dunn, director of the SPLC’s Learning for Justice program, which will shepherd the fellowship. “It was about uprooting the causes of white supremacy, about calling it out and naming it and really getting at the root of it.

“This was a family that, back in 1964, was radical in the very best sense of the word. This fellowship can remind us that the work has not changed and that we are also part of a larger fight. It is a reminder that we have so much work to do and such big footsteps to follow. We are standing on the shoulders of greatness, on the shoulders of boldness and courage. We are here on the battlefield of justice where people laid down their lives.”

A ‘mighty stream’

Since 1989, when the Civil Rights Memorial designed by Vietnam Veterans Memorial architect Maya Lin was installed, Klunder’s name has been among the 40 civil rights martyrs carved into it. Klunder Hardy was at the dedication. By that time, 25 years removed from the trauma of her husband’s death, she was a seasoned activist and teacher.

Even before Klunder died, his young wife had partnered with her husband in the civil rights movement to an extent unusual for women at the time. She had been at an overnight sit-in at the Board of Education the previous month and at the site of the school construction protest the day before her husband died – with the couple’s two young children.

In the aftermath, she became, overnight, both a working mother and a widow living a very public, painful grief. Undeterred, she moved her family into a majority-Black neighborhood in Cleveland – and then out again when her children’s needs required a new school – working in needy parishes and embarking on a series of teaching jobs while earning a master’s degree and shepherding her children to civil rights demonstrations and protests against the Vietnam War.

This weekend, Klunder Hardy, now an 87-year-old grandmother, will again be at the Memorial, where a film of water flows across the black granite like the “mighty stream” in Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Her children and other family members will join her. They say they are not there to remember a martyr – they insist Klunder did not want to be one – but to do their part to help push toward the dream of achieving a more just society.

That dream led to her father’s death, Janice Klunder said. And it became her mother’s life’s work.

“We’ll never get there completely, it is an ongoing process,” Joanne Klunder Hardy said. “It’s not like you can be involved and everything will be OK, because it’s not.”

Inspired by John Lewis

Joanne Lehman and Bruce Klunder met at Oregon State College, where Klunder, as an 18-year-old student in 1955, started raising money to support the Montgomery Bus Boycott. After Klunder graduated from Yale Divinity School in 1961, the young married couple moved to Cleveland, where Bruce Klunder became associate director of the Student Christian Union of the YMCA.

Ordained in 1962, Klunder became a leader in the civil rights movement in Cleveland. Believing that his religious calling demanded social activism, he was a founding member of the Cleveland-area Congress of Racial Equality, or CORE, demonstrating regularly for fair housing and against segregated public facilities and discrimination in hiring.

Joanne Klunder Hardy said that she and her husband were deeply inspired by the young John Lewis. In 1962, she said, they took a group of college students through the South to expose them to the realities of segregation. One night in Nashville, Tennessee, they had dinner with Lewis, then a student leader himself. As Klunder Hardy recalled the conversation, Lewis was recounting stories about the brutalities heaped on people participating in Freedom Rides and one student asked Lewis how he could say he didn’t hate the people responsible.

“He said, ‘Would you hate a blind man for stepping on your foot?’” Klunder Hardy said. “We were totally taken aback. People are blind, they just don’t understand, he was saying. That was the moment that got us started, seeing how he just kept moving forward. You know, what he taught us was, you can’t stop. You make a little progress and sometimes you take steps backwards, but gradually things are not the same.

“And things are not the same as they were in 1962 or 1964. Schools have been desegregated. Progress has been made.”

The protests by CORE that the Klunders joined came against a backdrop of a bitter fight by members of Cleveland’s white elite against integrating city schools in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education. Under pressure from civil rights groups and Black parents to integrate schools and to relieve severe overcrowding in substandard majority-Black schools in Cleveland’s urban core, district officials had begun to bus Black students to majority-white schools. However, officials made matters worse by segregating Black children within the schools – denying them access to the playground, lunchroom and recreational facilities, and cordoning them off from schoolwide events.

“In one school we saw,” Klunder Hardy said, “they propped the classroom door open so the Black children could listen to the sounds of the Christmas pageant.”

Under pressure, the Cleveland City School District opted, instead of promoting a policy of true integration, to build three new schools in majority-Black areas, which would have reinforced the pattern of segregated neighborhood enrollment.

CORE took the lead in attempting to stop the construction. On April 7, 1964, Bruce Klunder and about 150 protesters gathered at the construction site for the Stephen E. Howe Elementary School. Klunder lay down behind a bulldozer while three others blocked its forward path. The operator, who told police he was seeking to avoid the protesters in front of him, backed over Klunder, killing him instantly.

A transformation

The death of the young minister set off violence across the city, as protesters clashed with police. The next day, 150 people marched in silent memorial in front of the Board of Education building. More than 1,500 attended the funeral service. The death generated stories in newspapers and magazines in the U.S. and abroad.

The schools whose construction Klunder opposed were eventually built. Their establishment hardened racial segregation in the district and was used as evidence in a lawsuit – Reed v. Rhodes – brought in 1973 by the NAACP against the school district. In that case, U.S. District Judge Frank J. Battisti found that school officials in Cleveland had maintained a “dual system” based on race. In response to the opinion, the school district was forced to desegregate the schools, instituting cross-town busing and improving academics across the board. The school system remained under court supervision until July 2000.

Nishani Frazier, associate professor of history and American studies at the University of Kansas, is the author of a book about the role activists in Cleveland played in the civil rights movement. She calls Klunder’s death “a pivot point.” The activism that followed is among the major factors that led, Frazier said, to the election in 1967 of Carl Burton Stokes as mayor of Cleveland. Stokes, the first Black mayor of a major American city, became an inspiration to other Black leaders and was an important figure in early environmental protection efforts.

“Bruce Klunder is among the people, he is with the people, and when he is literally crushed into the ground, when people believe that this was intentional, whether or not it was, this transforms the movement,” Frazier said.

“The thinking is, if they would rather roll over a minister than do something as simple as desegregate, then it really does bring up the same fundamental question as did the death of Medgar Evers, and later of Malcolm X, which is whether it is really possible to sway the heart of the oppressor through nonviolent protest.

“So when Bruce Klunder is killed, the understanding begins to permeate the movement that racism is so intertwined with political and social structures that protest just isn’t going to be enough.”

‘A bridge to future leaders’

Today, as young leaders in social justice movements across the U.S. are echoing that driving force – seeking to tackle systems of racial oppression at their core – leaders at the SPLC say they derive inspiration from the story of Bruce Klunder and his family. Through the fellowship that will be established in the Klunder name, new young leaders will go into classrooms and work in institutions tackling racism at the ground level, said Tafeni English-Relf, director of the SPLC’s Alabama state office, which oversees the Civil Rights Memorial Center.

“We have an opportunity through this to really educate not just young people, but their parents,” English-Relf said. “The heroism of this mother and father is very much what this family centers, that this was their life’s calling. They were doing what they knew to be right. We can amplify that.”

Janice Klunder said she and her family have been longtime supporters of the SPLC’s work. Its mission to bring attention to injustice and work to improve the law resonates with the values she grew up with. It honors the legacy of her parents, who were always motivated, she said, by “an intensity on pursuing justice.”

“The driving force in their story has never been anger or hatred against individuals or a desire for revenge,” Klunder said. “It is about an ongoing fight against an unjust system. For us, this fellowship is a really great way to recognize the memory of my father and the life’s work of my mother and to sort of build a bridge to future leaders.”

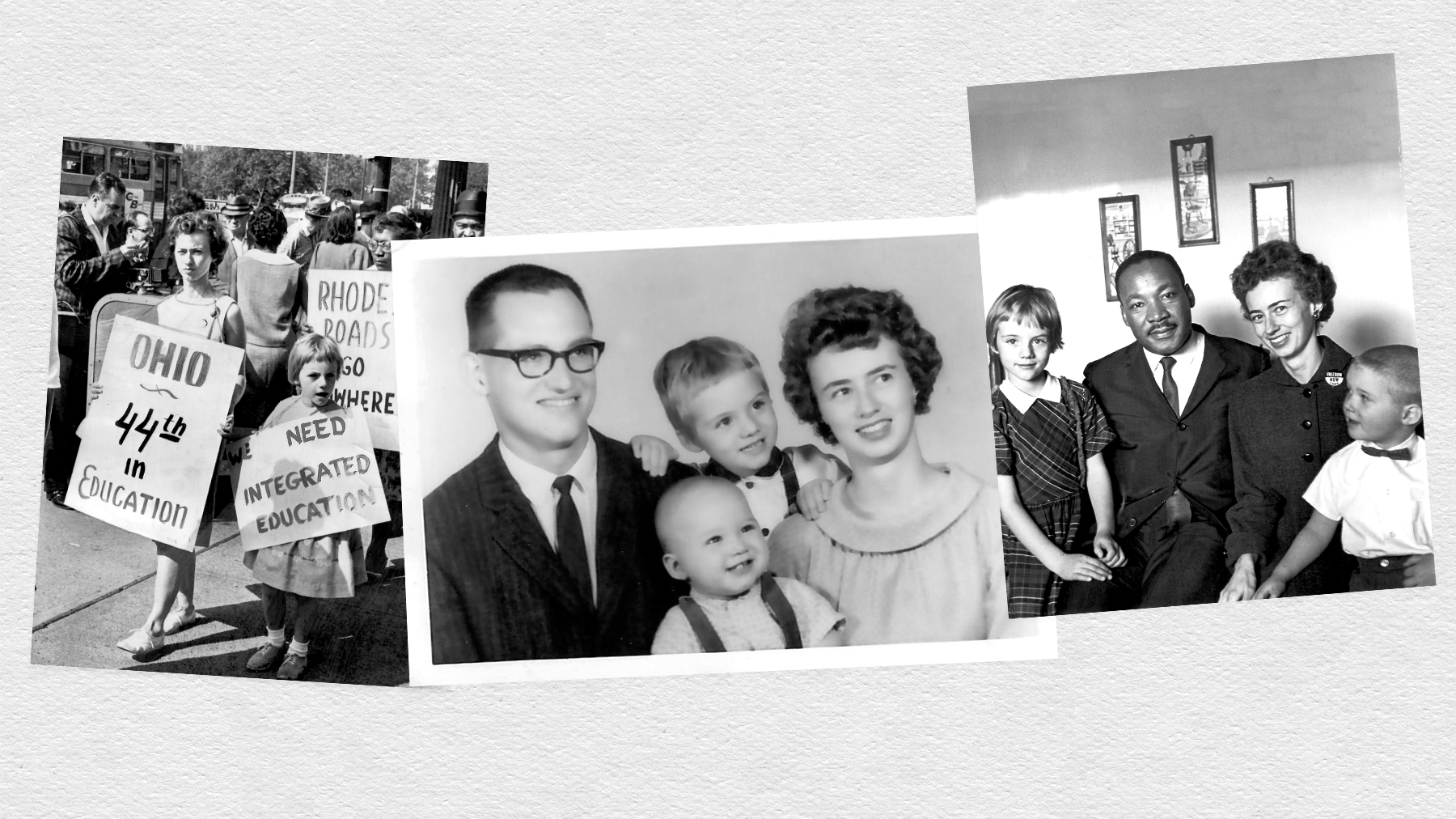

Pictures at top: The SPLC has announced the establishment of the Klunder Social Justice Fellowship, an initiative to advance systemic change and justice through engagement in schools and community organizations. The death of the Rev. Bruce Klunder in 1964 during a protest against school segregation marked a turning point in the civil rights movement. (Photo illustration by SPLC)