With the new presidential administration’s hard stance on immigration, many school officials are anxious about visits from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and uncertain about what to do should such a visit occur. While enforcement action by ICE has always been possible and does happen on occasion, the chances of such an event occurring at a school have historically been low. Moreover, for many years schools have enjoyed some protection in accordance with the “protected areas” policy issued by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). This policy provided that DHS generally should not take an enforcement action in or near a location that would restrain access to essential services or engagement in essential activities, such as a school, health care facility, or social services establishment.

However, DHS rescinded the protected areas policy on Inauguration Day (Jan. 20, 2025), leaving these institutions at greater risk of DHS enforcement action. While the risk of ICE activity at schools may still be relatively low, it is best to be prepared because such activity is more likely now than it has been in the past.

For Public Areas

- Anyone — including ICE agents — can enter public areas of the university without permission.

- Public areas include a dining hall or restaurant; parking lot; lobby; building hallway or foyer, etc.

- Being in a public area does NOT give ICE the authority to stop, question or arrest just anyone.

- No one can enter a private area of campus without the university’s permission or a judicial warrant.

TIP: To show that some areas are private (like classrooms or student lounges), mark them with a “Private” sign, keep the doors closed or locked, and have a policy that visitors and the public cannot enter those areas if not enrolled in classes or employed by the university.

For Private Areas

- Immigration agents can enter a private area ONLY IF they have a judicial warrant.

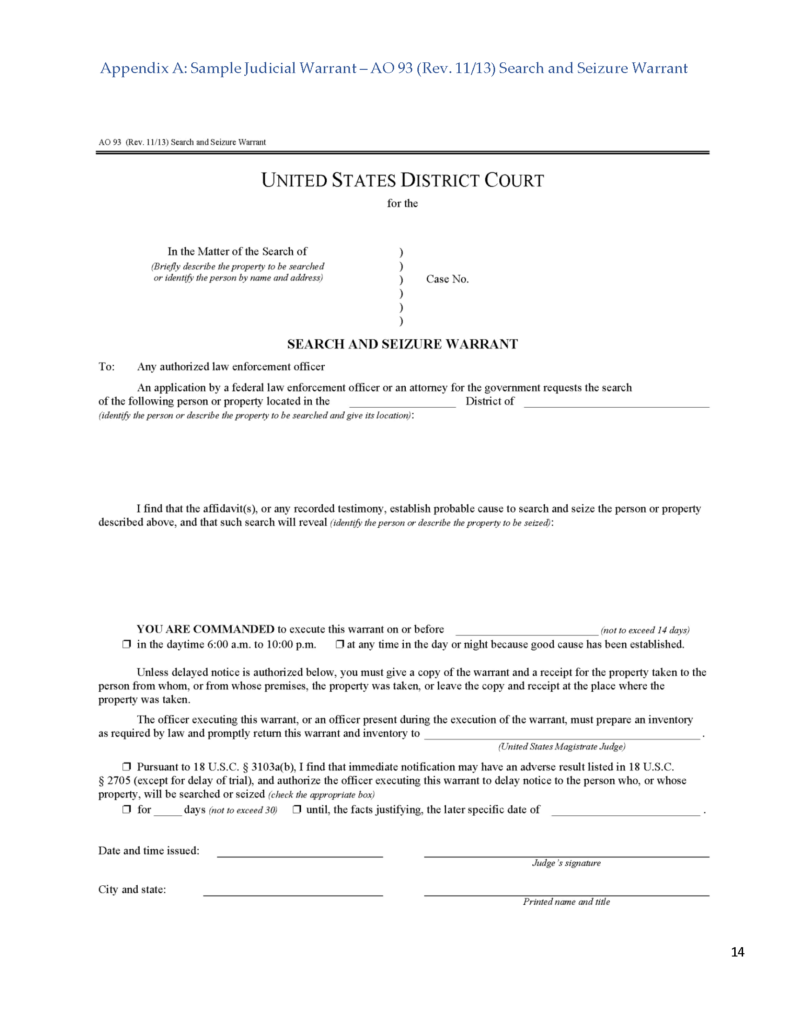

- A judicial warrant must be signed by a judge and say “U.S. District Court” or the name of a state court at the top and will include a time frame within which the search must be conducted, a description of the premises to be searched, and a list of items to be searched for and seized.

- Without a judicial warrant, ICE agents need official consent (from school authority) to enter private areas.

If ICE agents try to enter a private area, you should say: “This is a private area. You cannot enter without a judicial warrant signed by a judge. Do you have a judicial warrant?”

- If ICE agents tell you that they have a judicial warrant, ask for a copy and read it. If it is a valid judicial warrant, ICE has the right to gain access to the private area. In these instances, do not hide or assist employees, students or families in leaving school premises, provide false or misleading information, or discard any important documents or information. Obstructing or otherwise interfering with certain ICE activities can be a crime, and anyone involved may be subject to prosecution under federal law. That being said, you may (and should) still make efforts to ensure that any search or seizure is carried out lawfully.

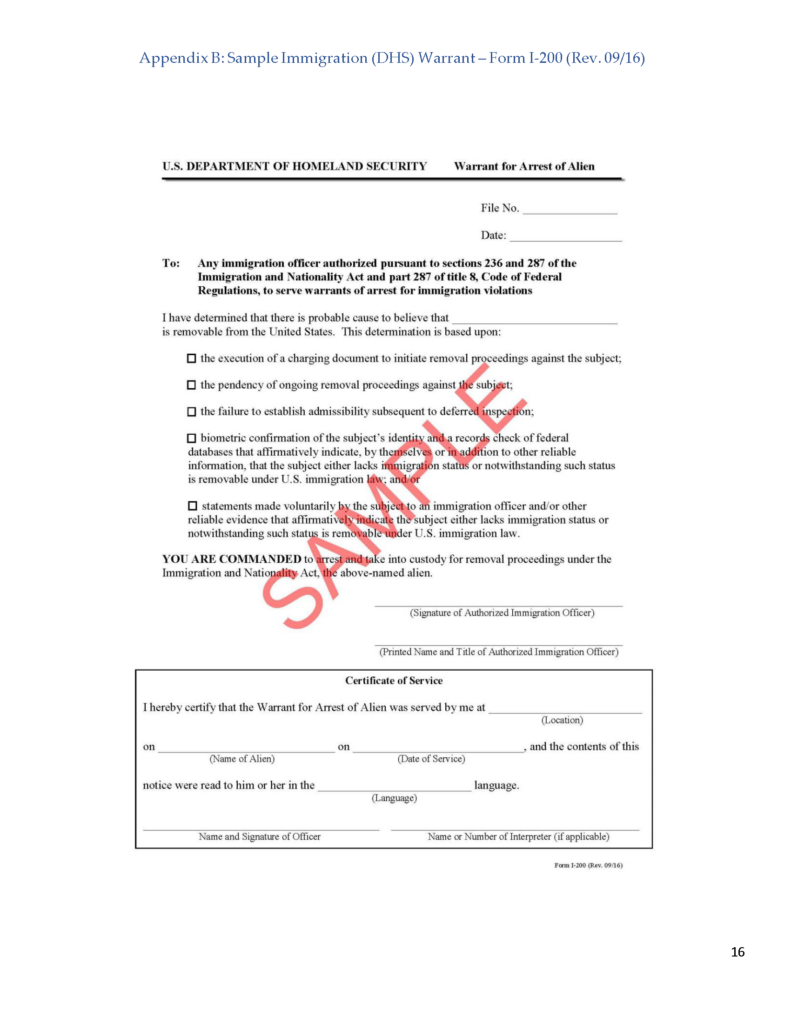

- Sometimes, ICE agents try to use an administrative warrant to enter. But an administrative warrant does NOT allow agents to enter private areas without your permission. Administrative warrants are not from a court. They say “Department of Homeland Security” and are on Forms I-200 or I-205.

Judicial warrant

Administrative warrant

During a raid

How do I know if a warrant is valid?

An immigration officer from ICE or CBP may not enter any nonpublic areas — or areas that are not freely accessible to the public and hence carry a higher expectation of privacy — without a valid judicial warrant or consent to enter. An immigration warrant is not the same as a judicial warrant; an immigration warrant does not authorize a search of nonpublic areas. If an ICE or any other immigration agency officer comes to your address demanding entry to search your premises or seeking to obtain evidence, and the officer has only an immigration warrant, you may refuse the officer entry and refuse to comply with the warrant because it does not grant the officer authority to enter or conduct a search.

Thus, if immigration authorities or other law enforcement agents present you with a warrant, it is crucial to check for the following:

Judicial Warrant

To be valid, a judicial warrant must:

- Be issued by a judicial court.

- Be signed by a state or federal judge or magistrate.

- State the address of the premises to be searched — make sure the stated address is their address or specifically pertains to them.

- Be executed within the time period specified on the warrant.

If the warrant includes all the above, then it is a valid judicial warrant, and you must comply.

However, if the judicial warrant is missing any of the above, lists a different address, or is being executed after the date specified on the warrant, then it likely isnot valid, and you may (a) refuse to comply and (b) ask the agents to leave.

Immigration Warrant

In contrast, an immigration warrant:

- Is issued by a DHS agency (look for a DHS seal, label, and/or the actual form number, i.e., DHS Form I-200, “Warrant for Arrest”; or Form I-205, “Warrant of Removal/Deportation”).

- Is signed by an immigration officer or immigration judge.

- Bears a title that will contain the word “Alien.”

- States that the authority to issue the warrant comes from immigration law, such as the Immigration and Nationality Act — and does not state that the issuing authority is a court.

If the warrant has any of the above characteristics, it likely is an immigration warrant and thus does not authorize the agent(s) to enter the premises. You may (a) refuse to comply with the warrant and (b) ask the agents to leave.

To determine what type of document you received, first scan the document for the word “warrant” or “subpoena”; usually, the document will be titled or labeled as one or the other. Also, skim through the document to confirm whether its content matches what the document claims to be in its title. If the document seems to generally authorize the officer or agent from ICE or CBP to conduct a search or make an arrest, the document is likely a warrant. If the document says that a person must appear in court at some later date to give testimony as a witness or that a person must produce or hand over certain papers, forms, materials, information, etc., then the document is likely a subpoena.

What do I do?

- Upon the arrival of ICE agents, request their names, badge or ID numbers, telephone numbers and business cards.

- Watch the agents carefully. Keep track of what they do. See if they are following what is written on the warrant. For example, the warrant may limit the areas the agents can search.

- Keep detailed records of the encounter. Make and keep copies of all documents given to the agent(s), as you are able. Take photographs or videos of the search, as you are able/comfortable. Prepare summary documentation of what happened.

- The best way for people to protect their rights is to exercise their right to stay silent and ask for an attorney. (Your school can inform employees, students or families that they have the right to remain silent and do not need to answer any questions, but do not direct them to refuse to speak to the agent(s)).

- If ICE agents ask for student records, remember that FERPA only permits school officials to disclose educational records without prior written consent pursuant to a court order or subpoena or a health or safety emergency. If the agents do not have a court order or subpoena, then FERPA prohibits you from disclosing these records without prior written consent from the student’s parents (or, if over 18 years old, the student). If the agent(s) do have a court order or subpoena, then the school must make a reasonable effort to notify the parent or eligible student of that court order or subpoena before disclosing the records (unless ICE or other federal officials are investigating an act of terrorism).