Neo-Confederate Activists Pressure Museum Officials to Distort History

Interviews with four history professionals who have faced neo-Confederate activism reveal that these radicals are pressuring history professionals to adopt distorted historical perspectives.

This August, the executive director of the Alabama Historical Commission, which owns and oversees major historic sites in the state, was forced to resign his position after what were described as conflicts with commissioners and Gov. Bob Riley over the director's support for civil rights preservation projects.

The episode was only the latest of the last several years in which museum professionals and preservation officials from around the South have come under sometimes severe pressure from neo-Confederate activists and their sympathizers, occasionally including harassment and various kinds of threats.

In case after case, members of groups like the League of the South and the Sons of Confederate Veterans have agitated against these professionals in a bid to push versions of history that mainstream curators and historians agree are bunk.

In North Carolina, the League of the South hate group attacked the Charlotte Museum of History because it was displaying a copy of the Declaration of Independence owned by television producer Norman Lear, saying that Lear had turned the declaration into "an instrument for liberal activism."

In Richmond, Va., a member of the board of the Museum of the Confederacy personally cut down a U.S. flag in the museum shop. And in Alabama, Lee Warner, the former Alabama Historical Commission executive director, told a reporter that many of Riley's appointees to the commission had opposed his plans to create a museum at the old Greyhound bus station, where Freedom Riders were badly beaten in 1961, and to memorialize the 1965 Selma-to-Montgomery civil rights march.

What follows are similar accounts from four others who have faced neo-Confederate activism.

Molly Hutton

Director of Schmucker Art Gallery, Gettysburg College // GETTYSBURG, Pa.

John Haley

Former Vice Chairman, Cape Fear Museum Board of Trustees // WILMINGTON, N.C.

Jean Martin

Curator of Old Depot Museum and Member, City Council // SELMA, Ala.

George Ewert

Director of Museum of Mobile // MOBILE, Ala.

Molly Hutton

Director of Schmucker Art Gallery

Gettysburg College · GETTYSBURG, Pa.

A planned 2004 art show, featuring criticism of the Confederate battle flag by a black artist, brought a deluge of neo-Confederate attacks on a small college gallery in Gettysburg, scene of a major Civil War battle. In the end, the show went forward, but not before the FBI and local police were called in because of death threats.

My situation was at least a year in the making. Late last year, I was planning an exhibition called "Art of the African Diaspora in the Age of Globalization," and my research led me to the artist John Sims. Although his work was not appropriate to a show on globalization, I showed John's work to the chairs of the college's Visual Arts and African-American Studies departments.

As I talked to more people about it, particularly the African-American community, it became clear that the Confederate [battle] flag was an issue for many people here.

Faculty members told me about being confronted by that flag when interviewing for their jobs — Gettysburg has tons of both Confederate flags and American flags. There are many, many tourist shops that sell memorabilia from both sides [in the Civil War]. The college does not have many students of color, and we're just north of the Mason-Dixon line.

It seemed like a really interesting environment to initiate a dialogue about some of the problematic issues that the Confederate flag brings up. And I still think that's important.

John Sims had an interesting story. He was a Detroit native, an artist and a filmmaker who took a job teaching in Sarasota [Fla.] and was struck by the ubiquity of the flag there. That's how he came up with the idea for the show we wanted to put on, called "Recoloration Proclamation: The Gettysburg Redress: A John Sims Project."

It involved recoloring the Confederate flag and enacting what he called "The Proper Way to Hang a Confederate Flag" — on a set of gallows. His idea was not so much about reconciliation as an exploration of the fact that this symbol is one of fear and oppression for many people.

As summer approached, John visited the campus and met with the PR department. In August, the department sent out a press release with a headline that said something like "Artist to Lynch Confederate Flag." Both the artist and I were a little worried that this was stressing this one piece in the exhibit too much. He called me right after that and said, "What are they trying to do, get me killed?"

Very quickly, groups like the SCV and others started responding. The Southern Poverty Law Center E-mailed me to give me a heads up on the widespread anger the exhibition was causing in neo-Confederate groups, including one E-mail that suggested blowing the gallery up.

We had just started to get E-mail on the show, and soon we were inundated. They got to everybody, the president, the provost, the pr department, John Sims, myself. They E-mailed the Gettysburg Chamber of Commerce and the merchants' organizations. And we got phone calls.

Ultimately, the SCV threatened to boycott the town of Gettysburg for a year. It was kind of misguided — the town had nothing to do with the gallery's decision to do this exhibition. Interestingly, early on we met with representatives of government and local merchants, and they seemed very supportive.

But once the boycott was threatened, we started hearing other things. From there, it just snowballed.

The pressure from the neo-Confederate groups was strong and threatening enough to make the college administration wonder if we should go ahead with it. The faculty for the most part was really supportive, and we got lots of letters of support.

But the threats did become more serious. Apparently, there were a couple of death threats against the college president, Katherine Will, and she has not even been inaugurated yet.

As our security became more and more involved, and then the FBI and the Borough of Gettysburg police, it became more and more clear that we potentially could have a major problem here. We heard about protests planned by the Council of Conservative Citizens [a white supremacist hate group], a Klan group, something called the Rebel Bikers and individuals, too. It was very scary. Multiple consulting firms were brought in, security and PR firms.

Ultimately, they suggested bringing what they called the "flash point" — the gallows — inside the gallery. But the artist said no. He had already agreed to leave the gallows up only for a few hours, rather than the three-week run of the exhibition that we'd planned. He did create an alternative piece that was an adaptation of the outdoor piece, and that was still quite effective. But he chose not to come to Gettysburg in protest.

This was all before the exhibition even opened. It was almost conceptual art in the making. On opening night, we had over 900 people in a 1,600-square-foot gallery. It was a huge crowd, an amazing crowd, of both locals and students. It was daily news in the local newspapers, and it spread to the Pittsburgh paper, Harrisburg — even the Washington Post did a story. It was quite a to-do.

The day before the opening there was a protest by about 30 people. On opening night, we were expecting hundreds, but only six or seven SCV members showed up. And for the most part, the people who have showed up have been very peaceful.

That was a very different tone from the E-mails. It's wearing to be called basically a piece of shit for two weeks straight. John got radically racist E-mails.

I collected all those E-mails and filled two huge binders with them. I thought part of this is about dialogue on the subject, and people should be able to read what was being said. Interestingly, the binders have really been the draw of the exhibition. The text that's been generated is almost like another work of art.

I came away surprised at the level of racism we'd seen in the E-mail responses. We know we live in a country with a history of racism, and that it's alive and well in many homes. But to see it and have it come directly at you was very surprising, as were the numbers. It was a shock to people. It was much more widespread than we had thought.

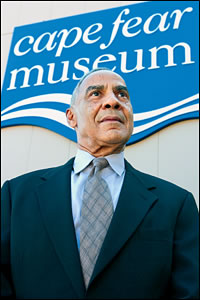

John Haley

Professor Emeritus, University of North Carolina at Wilmington;

Former Vice Chairman

Cape Fear Museum Board of Trustees · WILMINGTON, N.C.

John Haley, who served seven years on the Cape Fear Museum board, was the only professional historian on that body when it came under the sway of neo-Confederate activists or their sympathizers led by Bernhard Thuersam.

Thuersam, a native New Yorker who later rose to board chairman, joined the League of the South (LOS) hate group in 2001, becoming a local LOS leader and growing increasingly vocal on the board. Thuersam moderated a 2001 Lincoln-bashing forum at the museum that was addressed by LOS North Carolina chapter head Mike Tuggle; helped win board approval for a 2003 forum where a top LOS "scholar," Donald Livingston, spoke; and criticized efforts to investigate an 1898 race riot.

In the end, stymied by a move to rein in his board, Thuersam left. But so did a frustrated John Haley.

At the time that I was a member of the Cape Fear Museum Board of Trustees, there was a very vocal part of the board who were members of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, the League of the South, and even the United Daughters of the Confederacy. It seemed to me that there was an agenda to try to make the museum, a county-funded public museum, into an arm of these organizations, and also to make the museum's programming conform to the Southern version of the so-called Lost Cause.

While I was on the board [in 2001], there was an effort to actually erect a Confederate flag as part of a museum flag exhibit. It was supposed to go outside the building, on the main thoroughfare in Wilmington. This was in the aftermath of the flag struggle in South Carolina [where the NAACP boycotted the state because it flew the Confederate battle flag over its Capitol dome].

My question was, why did we as museum trustees want to use public money to erect something that obviously was going to be the source of controversy?

After the debate, I was the subject of several letters to the editor demanding that I apologize. But I decided not to get into a public debate. There were a lot of people who called expressing support, and I told them that the best thing to do was to quietly send letters or E-mails to the county commissioners [who, unlike the board, had managerial authority over the museum].

At around that time, somehow or other, a lot of museum "associates" — basically, financial supporters of the museum — were put on the E-mail list advertising activities and events of the League of the South, which was kind of strange. Evidently, someone on the board had taken it upon themselves to disseminate this information. A number of associates complained to me that they were going to withdraw their support from the museum entirely after reading this material.

Another incident occurred when the [Civil War] movie "Gods and Generals" was showing here in Wilmington. According to the local newspaper, the chairman of the board of trustees, Bernie Thuersam, was putting stickers on car windshields in the theater parking lot. Basically, they said if you want the real story, come to some of [the League of the South's] lectures and symposiums.

They have regular lectures. Of course, these people pass themselves off as historians, but I don't think any of them are really trained professionally. Basically, their tack is that the South went to war over values — not slavery — and to preserve a system of culture that the South felt was threatened.

Their history is grounded in the writings of the first wave of Southern historians after the war, who essentially said that the Civil War could be justified, that it was fought valiantly, that Reconstruction was an unacceptable thing. It's a history that among other things portrays all blacks in Reconstruction as crooks and incompetents. That's the version of history that they're frozen in.

There was another occasion where three members of the board, Bernie among them, made a trip to Raleigh to try to prevent the naming of a parkway here in Wilmington after Martin Luther King Jr. They announced in Raleigh that they were members of the board of trustees, which was right, but they also tried to lead some to believe that that was the museum's position. Of course, that was wrong.

It's hard to identify these people, but I think members of the League of the South have wormed their way into local government, boards and commissions, and I wouldn't be surprised if they're running for public office.

Here in Wilmington, I think those on the museum board were recognized as a potential problem for the county commissioners. Eventually, the commissioners changed the charter so that the board of trustees was reconstituted as a board of advisors, which is the right way.

Under the old system, the board wanted almost complete censorship over what was programmed and displayed at the museum. While technically it could not hire and fire, it could do almost everything else.

And if it wasn't about the Civil War, they were not enthused. They had to have major programming during Confederate History Month. And they used museum staff to work on these things. Now, since the charter change, Bernie has resigned — I guess the board could no longer be a platform for him.

As a professional historian, I have absolutely nothing against groups and individuals remembering history and heritage, as long as it's factual.

The greatest problem I had with the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the League of the South while on the museum board is they embraced a skewed and flawed version of history and they were attempting to use public facilities and public money to propagate the old Lost Cause.

In the end, I got tired of coming to meetings and not getting beyond the Civil War, or listening to Bernie giving some report about a Civil War museum he'd visited. It was like spinning my wheels. I felt I couldn't accomplish anything, and I decided not to continue. But now, the museum is doing great things. It's really beginning to realize its potential as a great county-owned museum.

Jean Martin

Curator of Old Depot Museum

Member, City Council · SELMA, Ala.

At age 81, long-time Selma resident Jean Martin was overwhelmingly reelected to the City Council this September. The vote was a moral victory for Martin, a white woman who came under bitter attack from neo-Confederate activists for providing the 2001 swing vote that resulted in moving a bust of Nathan Bedford Forrest — a slave trader and Confederate cavalry general who later became the first national leader of the Ku Klux Klan — away from the courtyard of a public building, where it had been erected by a group called Friends of Forrest a short time before, to a city cemetery. Two white and two black council members voted against her.

The first I recall hearing about the Forrest statue was at City Council. I was under the impression that it was going to be a finely done bust that would go on a pedestal inside the Smitherman Museum [a former Confederate hospital named after a long-time Selma mayor], which was all right with me.

I'm no admirer of Forrest's, but it is a museum and, of course, he was a part of Selma's history. [In 1865, Forrest led an unsuccessful defense of Selma, which was partly sacked.]

I really didn't think any more about it until the week [in October 2000] that Selma's first black mayor was to take office, when we learned that it would be placed outside the Smitherman building, which is in a predominantly black neighborhood. I felt that was wrong.

There was a lot of discussion at council meetings. It made all the newspapers. At one time, the council voted to leave the statue alone. But then all the disturbance began. There were attempts to topple it, attempts to protect it, and constant newspaper coverage, negative for the most part. And truly, Selma needs no negative newspaper coverage. It's had enough.

I began to think very deeply about it, because this is my town and I love it. I talked to a businessman I know very well, and he said, "Jeannie, put it in Old Live Oak Cemetery. If he has to be here, that's where he belongs."

Our cemetery is beautiful, a National Trust, and we have a Confederate Circle there. I thought that made sense. I contacted other people and began to talk to them about it.

During this time, my youngest sister died in Houston and I flew out for the funeral. And bless me if the headlines in the Houston papers were not all about that statue. Pat would have been so angry about all that mess!

I prayed about it, and I thought, "All right, no matter what it takes, this is what I have to do because it is the right thing to do." And I caught hell, although my mother would not have liked me to say that!

It took almost no time for Mrs. [Pat] Godwin and the Friends of Forrest to start. [Friends of Forrest, in which Godwin is a principal, owns the bust.] They came to council meetings. They wrote letters to the paper. She conducted an E-mail campaign, and I don't need to tell you what she said. I was shocked at the E-mails. It was very unpleasant. I received ugly phone calls — you know how they act. I received anonymous letters at home, too.

I also heard frequently from [neo-Confederate activist] Ellen Williams. It was mean, mean, I don't have to tell you. Still, I thought what's happening to me is nothing compared to what happened to the families of my Jewish friends.

But it got to me, and I talked to my rector several times. Sometimes, you begin to think you've lost your mind. To make such a fuss over the man who founded the Klan!

We have his portrait here in this museum [Martin is the curator of Selma's Old Depot Museum] and I will not deny that he had his place in history. But history is past. You don't try to live in the middle of it, at least I don't think you do.

This so-called romantic view of the Old South — if these people were suddenly picked up and placed in the Old South, they wouldn't find it so romantic. It [the Civil War] was a war that shouldn't have happened. But it did, and parts of the South have never recovered economically from that.

I also received an E-mail from someone I had grown up with, who was a very close friend in the years after my husband died. His E-mail said simply, "What are you going to do with your thirty pieces of silver?" I think that was the angriest I felt during the whole episode.

Also, after we moved the statue and we were being sued by Friends of Forrest, a complaint was made to the ethics commission saying that I received a pay raise from the city of Selma at the museum because I had helped the mayor move the statue. Now, that's ridiculous.

Some things got to be funny. For instance, I received a good deal of criticism because we had not placed the general facing north — so he could combat his enemies! That one got to me. I mean, really.

Pretty soon, it finally began to calm down. I had been assured that if and when he was placed in the cemetery, there would be no vandalism, and there has not been, not one bit. Life went on, and the old boy's still in the cemetery.

Now, I've just been reelected to the City Council. But on the weekend prior to the election I received a phone call from someone who told me that yard signs had been placed all over my ward saying, "Remember Forrest, Martin's Got To Go." There was a funny sidebar.

I later had an anonymous phone call from someone who said more than 40 signs had just disappeared from my ward. I said, "You mean my signs?" He said, "No, no, they were the signs saying 'Martin's Got To Go.'" I don't who it was, but wasn't that wonderful? I also received endorsements from ADC [Alabama Democratic Conference] and the New South Coalition [the state's two largest black political groups].

I am so delighted to tell you that in the end, I won by a very large margin, which tells you that a lot of people are finally beginning to grow up. I hope so. We need to all go together.

George Ewert

Director of Museum Of Mobile

MOBILE, Ala.

For several years, Mobile has been roiled by a small but very active group of neo-Confederate activists who have managed to push city officials into accepting a number of their demands. The conflict came to a head in 2003, when museum director George Ewert was attacked by these activists and threatened with firing.

In the last five years or so, there has been in Mobile, as in other parts of the South, an increase in political activism by the so-called heritage and neo-Confederate movements.

Locally, it's revolved around two issues. The first was the question of which of the Confederate flags was the appropriate one to fly on city property in Mobile. The second came about as a consequence of my writing a negative review of the movie "Gods and Generals."

Since the early 20th century, Mobile has used "the city of five flags" as one of its slogans and has flown flags including what is typically called the Confederate battle flag. A few years ago, after a complaint from an African-American gentleman about that flag, the mayor of Mobile, Michael Dow, appointed a blue-ribbon committee of concerned people and public and academic historians.

The committee ended up recommending that we fly the first national flag of the Confederacy. But members of the Sons of Confederate Veterans [SCV] and other activists took grave exception to that and recommended the third national flag instead, since it has a small battle flag in one corner and so would still be present. After a stirring debate on the City Council, it was that flag that was adopted.

This episode encouraged and emboldened the local SCV and neo-Confederates and helped to show them that they had political clout in the city of Mobile. That realization helped them decide to mount a political campaign against me last year, after I wrote a review of "Gods and Generals" [a major feature film about the Civil War] that was published in the Intelligence Report of the Southern Poverty Law Center. (See Whitewashing the Confederacy in Intelligence Report issue 110, Summer 2004.)

It was a very negative review and pointed out the fact that the movie was a rehashed version of praise for the myth of the Lost Cause, a view that is very well documented as a myth, but that is nonetheless very near and dear to these heritage organizations.

Their campaign took a variety of forms, including a great many E-mails to the mayor and council members and personal meetings with these officials as well. They wanted me terminated as a "cultural bigot" against Southern history and said that I was disqualified as caretaker of the city's history. They asked for time to denounce me in public City Council meetings, as well as before the Museum Board, which operates the Museum of Mobile.

There were also a variety of postings on neo-Confederate Web sites and blogs that very strongly denounced me and mischaracterized what I had done, primarily by claiming that I wrote the review as director of the museum, not as a private individual.

At the conclusion of one of the City Council meetings where I was denounced, the chairman of the council, Reggie Copeland, demanded that the mayor make me apologize. That afternoon, in a closed-door session, Mayor Dow asked me to write a formal apology or receive a written reprimand, and I was threatened with termination if I wrote similar articles.

Naturally, I was distressed about this. I felt it was a violation of my rights and an unwarranted intrusion of politics into my personal and professional life, and also into what I did as director of the museum. I began to communicate with a variety of my colleagues, historians and museum professionals, who began an ardent campaign in support of me, sending E-mails and letters to the mayor and council defending my right to speak freely on a matter of history.

The mayor then changed his approach and asked that anything I might write personally that would be controversial be reviewed before publication by him or the chairman of the Museum Board for their pre-approval. This effort at political censorship was as egregious as the threat to terminate me if I didn't cease writing "controversial" articles. When this was communicated to my colleagues, an even greater flood of letters and E-mails began to flow in.

At this point, the mayor did not communicate with me any further for a number of weeks, nor did I hear anything from any City Council people. In the interim, I attended the Southern Historical Association's annual meeting in November of 2003 and was asked to give an impromptu session along with some other historians on the growing influence of the neo-Confederate movement. I was very gratified to receive an enormous amount of support from my colleagues.

Since that time, the mayor has acknowledged to me, no doubt as a result of the E-mails and other comments from historians from all across the United States and as far away as Japan, that had he the opportunity to do this all over again, he would do it very differently. Apparently, he felt the incident had been poorly managed, and I agree.

The whole affair reflected the fact that a small, energetic group of individuals can unduly influence political decisions. This movement is far more widespread than the public knows. It currently operates below the radar of national attention.

And you never know what you might say that will be seen as a neo-Confederate "heritage violation" that will bring you under attack and may quickly escalate into something that threatens your whole life.

Here in Mobile, some on the council and the mayor initially gave in to the "heritage violation" accusation because they sought, in part, to minimize a local controversy — it was seen as a distraction from other pressing matters. But this effort to silence or punish me for my views fortunately failed.

Until public officials, educators, and others in authority realize that efforts to hurt people for criticizing the myth of the Lost Cause are wrong, and that that myth does not represent mainstream scholarly history or broad public opinion, others will likely repeat the kind of episode I experienced.