Seeing Evil: A Scholar Discusses Conspiracy Theories in America

Scholar Michael Barkun discusses conspiracy theories and the dangers they pose to the political process

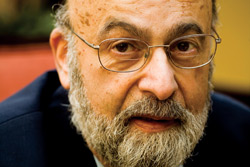

Michael Barkun is a professor emeritus of political science at the Maxwell School, Syracuse University. A leading expert specializing in political extremism and the relationship between religion and violence, Barkun is the author of numerous books, including Religion and The Racist Right: The Origins of the Christian Identity Movement and A Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America. The Intelligence Report interviewed him about conspiracy culture in the United States and how it flourishes.

Why does the American far right provide such fertile soil for conspiracy theories?

One reason is that those on the far right need an explanation for their continued lack of power and success. One way to do that is to create a vision of politics dominated by an invisible but immensely powerful evil force pulling the strings. According to that conspiracist view, the political leaders we see are only the "front men" for the real power-holders operating behind the scenes, the ones keeping the far right from gaining what it wants.

What has changed over the years, and what remains the same?

Clearly, the Internet allows ideas to spread and become "mainstreamed" much more easily and quickly. Notions that once would have remained within isolated subcultures can now spread to the larger society with astonishing speed. Just think of the "birther" phenomenon. On the other hand, there are certainly continuities — for example, hostility toward financial institutions and immigration, both of which were common among conspiracists in the 19th and 20th centuries.

What's the most striking aspect of today's resurgence in conspiracy culture?

I think it's the way conspiracism has blended into popular culture. That is, it's become an element in mass popular entertainment. We see it in popular literature, television programs and films. One need only point to the novels of Dan Brown or "The X-Files." Now, it might be said that such treatments trivialize the ideas and sanitize them, in the sense that they separate the ideas from some of their more sinister political implications. But conspiracy beliefs have now become so common in popular entertainment that they have been legitimized.

Is it possible to convince conspiracists that they are wrong through the use of sound logic and copious evidence?

Yes and no. If the conspiracy idea involves a single, limited event — say, the 9/11 attacks — it may well be possible to convince a believer that he or she is wrong based on a marshalling of evidence. On the other hand, if the conspiracy idea is more sweeping — say, the belief that the Illuminati or the Trilateral Commission or some other cabal controls world politics — then the likelihood is that attempts will fail, for two reasons. First, believers in these kinds of sweeping conspiracy theories often believe that seemingly contradictory evidence has been cunningly planted by the conspiracy itself to mislead the unwary. Second, believers often think that those trying to debunk conspiracy theories are allies of the conspirators. This is especially true if the critics are, say, academics or journalists.

Why are conspiracy theories dangerous?

The danger of conspiracy theories lies, first, in their oversimplification of the political process; second, in their tendency to look for scapegoats upon whom blame might be heaped; and, third, in the likelihood that they will push believers entirely out of the political process, since many conspiracy theories assert that political institutions are irrelevant. This last danger is the most serious, since those alienated from the political process may choose violence rather than the ballot box.

Interview conducted by Alexander Zaitchik