Leaving the Neo-nazi Lifestyle, and Tattoos, Behind

Bryon and Julie Widner decided to quit the world of hate. But former comrades, and Bryon’s tattoos, made it an uphill struggle

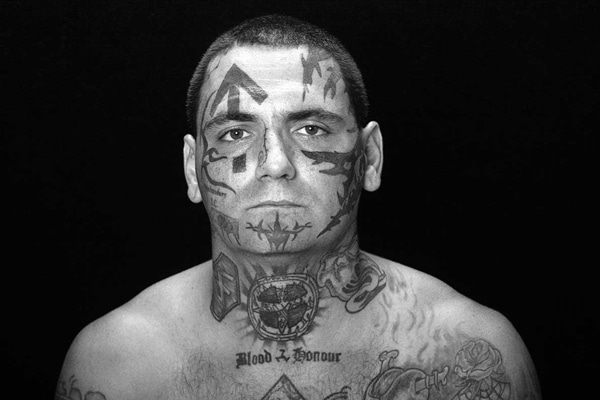

Bryon and Julie Widner were hard-core racists. Bryon, nicknamed “Babs,” was so committed to the cause that he tattooed his body with racist emblems, including his face, which depicted a bloody straight razor, his weapon of choice. Now 34, Bryon co-founded the Vinlanders Social Club, once one of the most notorious and violent racist skinhead outfits in the country. Julie, now 40, became a leader in the neo-Nazi National Alliance during approximately the same period.

In 2005, Bryon and Julie met at a hate music event and it changed their lives. They married later that year and had a son (they also are raising Julie’s other four children together). After spending 16 years as a vicious brawler and razor-carrying skinhead enforcer, Bryon realized he didn’t want to raise his family in the hostile culture he once embraced. But he knew that his marked face would forever frustrate his efforts to rejoin the respectable world. In a courageous move, the Widners reached out to the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), their longtime enemies, for help.

Against daunting odds, both Widners made a permanent break with their pasts. Bryon’s path entailed excruciating physical pain, as he underwent some two dozen laser treatments to remove the tattoos from his face and neck that made it impossible for him to find work. The treatments, which were documented in the recently aired MSNBC film, “Erasing Hate,” were made possible by a generous donor to the SPLC, which had long tracked the Widners. Bryon and Julie Widner spoke to the Intelligence Report in September about the white supremacist movement and why they left it.

What first drew you to the movement?

BRYON WIDNER: I first became a skinhead at 14. We lived in Albuquerque, N.M., in the predominantly Mexican North Valley. When I was young, I didn’t like white people. I learned about skinheads from a relative who was one in the late 1980s. He didn’t indoctrinate me; he just gave me a taste of the lifestyle. To impress him, I shaved my head and drew swastikas and upside-down crosses on my jacket. I got beat up a lot for this. Any normal person would have grown their hair out and quit. I decided to stick with it, probably because in that area white kids got jumped a lot.

But I didn’t meet any serious white power skinheads for some time; there weren’t many in Albuquerque. I met my first white power skinhead when I was about 17, when a whole crop just came out of nowhere. This was long before the Internet. There was no way of getting information easily. If you wanted to hear racist music, you had to mix a tape. We had to do it old school.

JULIE WIDNER: My parents divorced when I was about 9 and my mom ended up a single parent. She worked all the time. When I was 13, I had a mohawk, a swastika shaved on one side of my head, and an anarchy sign on the other. Even though I was living in a very nice part of Arizona, I would tell people Hitler wasn’t that bad of a person. I didn’t think of myself as a racist. I was just rebelling against society. But I know now that I was raised in a family with racist beliefs. My father raised us in that environment, in the Detroit area. You kept to yourself, didn’t intermingle, didn’t date someone not of your race.

I got pregnant with my first son at 17 and dropped out of high school. I had two kids by 19 and a failed relationship, but it wasn’t until my late 20s that I actually found the movement. I met some skins from Tempe, Ariz., and they thought since I was new I should take baby steps. And baby steps meant joining the National Alliance [NA].

What about the racist scene appealed to you?

BRYON: It was a family thing. I was a street kid, a chronic runaway. It got to the point that my dad told me to call every couple of weeks to let him know I was alive. So I didn’t have any family but my new family, a small skin group we called the Soldiers of the New Reich. I found out later that my family really did care about me.

JULIE: For me, it was the excitement, because I had been a single mom for so long. All I did was work and take care of kids. And one of the skins I met from NA meetings, I ended up marrying him. I joined the NA in 2002 or 2003. After my husband died in a car crash in 2003, I became even more active after moving to Michigan. I was alone with the kids and they took me in as family. And I was really active on [the racist Web forum] Stormfront.org. I even ended up moving some prominent racists to my town and some stayed in my house. I traveled with a bunch to EURO [European American Unity and Rights conference, a gathering of white supremacists held near New Orleans by former Klansman David Duke’s organization] in 2005. The nametags had your name and your Stormfront screen name, so we got to know each other.

Tell me about your time in the movement.

BRYON: After the Soldiers [of the New Reich] fell apart, we went our separate ways. I got into some legal trouble, bounced around and landed in Indiana. In 1999, I met the guys from the Northern Hammerskins [a racist skinhead group]. They were all huge body builders. They were completely covered in tattoos, frightening looking and a solid unit. Their leader, Jeremy Robinson, was really charismatic. He was the kind of guy you would follow to the gates of hell. But I never got my patch because of legal trouble — I would get in bar fights. I always had anger issues.

Once I cleared up my legal problems, the Outlaw Hammerskins [OHS] had formed. Jeremy [Robinson] remembered me from the parties that I went to, but I didn’t see him for a couple years because I was in and out of jail. I brought [future Vinlanders Social Club (VSC) co-founder] Brien James to meet Jeremy, and we got drunk. Our claim to fame as OHS was the fact that we basically took on the Hammerskin Nation [then a dominant racist skinhead federation that included the Northern Hammerskins] and showed they were too chicken shit to shoot us. All the other skinhead crews saw that the Hammers were a joke. Our tattoos and Web presence made us look like a very, very extreme group. For the most part, we just kept to ourselves, and it was very rare if anyone was shot or stabbed. But OHS fell apart after Jeremy left around 2002 or 2003. He was paranoid and scared and just gave up.

JULIE: I was a loyal NA activist for years. Things changed after I found out that [NA Chairman] Erich Gliebe was dating a stripper. I have always been anti-smut. I didn’t even know he had a girlfriend, because he would call me and say, “What are you wearing?” I would say, “What do you mean what am I wearing? I’m in my pajamas, let’s talk business.” I talked to Gliebe a lot on the phone and all of a sudden I find out that he’s marrying a stripper? Even worse, in 2002, when Gliebe told me [NA founder and longtime leader] William Pierce died, he said Pierce had a huge pornography collection. So when I found out, it was an easy decision to make, I was gone. I joined [the racist skinhead outfit] American Front, but I never got my patch.

How did the Vinlanders Social Club come about?

BRYON: I was basically the last man in OHS. The day after I turned in my patch, Brien James started talking to me about forming the Hoosier State Skins. A bunch from OHS jumped on board, Eric [“The Butcher”] Fairburn, Jon Carr. We were blackballed from the movement because of OHS’s threats against the Hammers. We really didn’t care. We told everyone on the Net that we were a white power group and if they didn’t like it, they could f--- off.

But Brien had delusions of grandeur that he was the next führer and would take over the white power movement. Even so, I jumped on board because it gave me a chance to beat up some Hammerskins. I was an enforcer, after all. If another crew was worth a damn, I would bring them on board and run off all their buddies. But the ego battles between Brien and Eric started to really hurt VSC. Everybody thought Eric was the VSC “president” because he was loudest on the Internet. And he loved it. But Brien didn’t.

When did things start to go sour?

BRYON: My doubts started even in OHS. My brothers abused women. I had always been very adamant about not kicking the crap out of girls. My image of a skinhead was basically a guy who worked hard and took care of his business. Your work and family comes first and after that you make time for the guys. But apparently that just wasn’t the deal. I was preaching white women are the holiest things in the world, but they thought they looked better with black eyes. I didn’t want to say anything because I was afraid they’d shoot me. The OHS guys were pretty scary, so I just keep my mouth shut. One of the crutches I used was alcohol.

What hypocrites! I mean, nobody cared about their kids, or their family. They had bastard children all across the country. They didn’t pay child support. All they cared about was drinking and committing felonies.

JULIE: It started for me at Nordic Fest [a major white power concert in Kentucky May 2005], where I first met Bryon. Nordic Fest reconfirmed concerns I already had. None of the women I’d met had their children. It seems like all the skinhead chicks had their kids taken away or their parents were raising them. It’s about drinking and partying — not about furthering any agenda.

And then at Nordic Fest, there was a 17-year-old girl and she was in a tent having guys go back and forth. I put an end to that. But there was another tent with another girl that the guys were taking turns with, too. It was supposed to be a family event! By the time Bryon and I started talking after Nordic Fest, we had so much to talk about and we were on the same page. And six or seven months after that, we got married and Bryon came to live with me in Michigan.

And then it got worse because Bryon’s buddies were mad that he was closer to his family than them. Here we are trying to make a life — we’re married and having a child — and everybody is turning against us. Then Eric [Fairburn] came to see what we were up to. They were partying every day. One night we were at a lake and the guys were trying to get Bryon to come with them. They were all hell-bent on kicking some guy’s ass, some Klan member. I leave, go home and I get a phone call asking what medications is Bryon on—he’s at the hospital and the doctor wants to know.

Here we are trying be a family and they come out and they start drinking and Bryon is at the hospital. They’re trying to tell me that it’s none of my business as his wife. After that, Bryon decided no more drinking, because we fought, too, when he drank. And that’s also when the phone calls started, around the middle of the summer of 2006. They were calling at 3:30 a.m. and hanging up or saying, “You’re going to die.”

How did you actually leave the movement?

BRYON: There wasn’t any kind of definitive moment when I just said, “I’m done.” It was the culmination of a lot of things as I slowly opened my eyes. Once the death threats started happening… It was the most ridiculous, unbrotherly thing in the world. That’s when I hung up my boots. Julie was done long before that. I contacted [black anti-racist activist] Daryl Jenkins and we became friends. Then I reached out to former skinhead T.J. Leyden, whom I’d been following on the Web. He told me to call the SPLC. That was February 2006.

What was it like sitting down with your mortal enemies?

BRYON: It was incredibly strange. I mean, [SPLC co-founder] Morris Dees? He was the guy that hid under your bed and shut down your crews, Public Enemy Number One. I was nervous.

How did your tattoos affect your life at this point?

BRYON: I couldn’t get any decent jobs. Half of the people wouldn’t give me an application because of the way I looked. It sucked and I needed to feed my family. I even talked to Julie about getting some dermal acid on eBay. I was going to test it out on my hands first and see how it worked and I was going to douse my face in it. I figured if I did that enough times the tattoos would come off.

Tell us about why the film, “Erasing Hate,” was so important to you?

BRYON: I agreed to do the first couple of laser treatments without anesthesia. It was one of the most excruciating things that I’ve done in my life. But I felt like I deserved it. It was penance.

It took 24 separate treatments to get the tattoos off. But if I can prevent one other kid from making the same mistakes I did, if I can prevent one other family from having to go through what I put my family through, maybe I can redeem myself. And it’s really amazing. People have said that I have touched their life in positive ways. I never once thought I would ever touch anyone’s life — except maybe by punching them.

Related Profile: