Roots of the ARA

Before Anti-Racist Action, a small group in Minneapolis called the Baldies laid the groundwork for bare-fisted anti-fascism

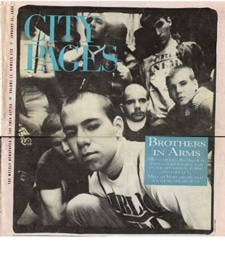

Before there was an Anti-Racist Action there were the Baldies, a now legendary multiracial band of seven teenagers looking for adventure in 1980s Minneapolis, Minn. There was Mic Crenshaw, a black kid originally from Chicago, Gator, a mix of Native American and Latino, and five working-class white kids. They hung out together, skateboarding, drinking beer, listening to Public Enemy and punk music. They passed around copies of The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Seize the Time by Bobby Seale and Nick Knight’s book of photographs, Skinhead.

They saw themselves as skinheads — real skinheads — the true descendants of the tough white and black working-class kids who together created the skinhead style and substance in the streets of England in the late 1960s. But in the States, says the now 42-year-old Crenshaw, the media fixated on the heretics, the fake skins, the snarling Nazis who broke Geraldo’s nose with a flying chair on national television. The Nazi skins and their adult Svengalis like Tom Metzger, the former California Klan leader, were hijacking the culture. The Baldies were determined to take it back. “We knew we had to assert we were skinheads and we were not racists,” he says.

Vicious brawls broke out at punk rock shows, house parties and other youth hangouts in Minneapolis when a racist skinhead crew from across the Mississippi River in St. Paul, the White Knights, began appearing on the scene, shouting “White Power!” as they beat up people of color and anti-racists. If they had the slightest inkling that someone was gay, that person got stomped too. Harder. That’s when, Crenshaw says, “We decided it was our responsibility to organize ourselves into a fighting force to make sure they didn’t feel comfortable coming around and acting like Nazis in our city.”

Anywhere the White Knights showed up, the Baldies followed. As the violence increased, so too did the pressure on the young antis from teachers and older political activists they looked up to. “They would pull us aside and ask us what was going on and tell us we were being stupid, macho, suicidal and that no good end would come out of retaliation or vengeance,” Crenshaw says. “We felt a moral obligation to meet violence with violence at the time.’’

Similar struggles and debates were taking place across the country as racist skinheads began appearing in significant numbers. In 1988, racist skinhead violence erupted across the United States, with scores of violent attacks and murders over the next four years.

Still, says Kathleen Blee, a professor of sociology at the University of Pittsburgh and author of Inside Organized Racism: Women in the Hate Movement, in the early days at least, ideology and politics had little to do with the conflict for most of the warring skins. They were more like street gang members, lost and lonely youth, attracted to the excitement, the violence, the sound of sirens, the sight of blood. They were the Sharks and the Jets, the Antis and the Boneheads. Which side someone belonged to often depended on who their friends were or the parties they attended. Blee says the boundary between racist skinheads and anti-racist skinheads was “often permeable.”

“Political commitment for these young kids was really paper-thin,” she says.

By 1989, the Baldies had declared Minneapolis a Nazi-free zone and put the word out to anti-racist skins and their allies throughout the Midwest to come to Minneapolis to party and organize. “There was a lot of debate,” Crenshaw says. “We were very self-critical every step of the way. But we were very clear we were a political force and organization that was very consciously anti-racist.”

Even though it was January in Minnesota, more than 100 people from Chicago, Detroit, Milwaukee and other cities showed up and agreed to form a new anti-racist movement that would share information and ideas, and put boots on the ground in places battling the Nazi surge. They also agreed the movement would be, as Crenshaw says “rooted in action, not theory.”

“It wasn’t just skinheads any longer,” says Crenshaw, now working as a musician and labor organizer on the West Coast. “Once we started to branch out beyond Minneapolis we ran into all kinds of different people who wanted to work with us. There were anarchists and communists and people who thought they were patriots, almost right-wing. But the common thread was a commitment to anti-racism.”

Thus ARA was born.