More Harm Than Good: How Children are Unjustly Tried as Adults in New Orleans

The Orleans Parish district attorney is prosecuting children as adults in unprecedented numbers.

Editor’s note: Six months after the publication of this report, Louisiana passed legislation endorsed by the Southern Poverty Law Center that raised the age when a person can be tried as an adult to 18, though 17-year-olds charged with certain crimes are still eligible to be tried as adults. Beginning Aug. 1, 2018, the law takes effect for juveniles charged with nonviolent offenses. Two years later, the law will extend to juveniles charged with violent offenses.

The Orleans Parish district attorney is prosecuting children as adults in unprecedented numbers. Although nothing in the law requires Louisiana prosecutors to charge children as adults, District Attorney Leon Cannizzaro chooses to transfer children to adult court in almost every possible instance. He transfers children who have no prior delinquency record or played a minor role in the alleged crime. He transfers children who have a mental illness or developmental disability. He even transfers children accused of nonviolent offenses. Some of the children he transfers are found innocent of any crime – but only after enduring the stress and danger of the adult system.

Prosecuting children as adults is, in fact, Cannizzaro’s default practice. Between 2011 and 2015, his office has transferred more than 80 percent of cases involving 15- and 16-year-olds charged with certain offenses where there was an option to prosecute in either juvenile or adult court. Under state law, a judge has no say in these decisions. Discretion rests solely with each parish’s district attorney.

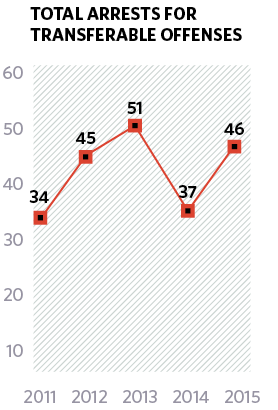

Cannizzaro has sent 200 children to adult court since assuming office in 2009, but it has not made us safer. Arrests for offenses eligible for transfer to adult court are up. Recent data also show that teenagers prosecuted in Louisiana’s juvenile justice system are less likely to reoffend than those prosecuted in the adult system. The district attorney’s practice is wrong for New Orleans’ children, their families and the community. It does more harm than good.

This report by the Southern Poverty Law Center examines the Orleans Parish district attorney’s approach to the prosecution of juveniles and the process known as juvenile transfer. It shows that Cannizzaro’s use of default transfer is unfair and ineffective – it fails to protect public safety, conserve public dollars, or respond appropriately to juvenile crime.

Experts agree that adult prosecution is often the wrong response to juvenile delinquency.

Research consistently demonstrates that prosecuting children as adults increases the likelihood that they will end up behind bars again. As a general matter, juvenile transfer also unjustly treats a child as a fully formed adult when science shows that young people’s brains – and their decision-making abilities – are still developing.

The sentences that transferred youth receive in Orleans Parish are often the same as they could have received in the juvenile justice system. But young people in the adult system will serve those sentences without the services offered by the juvenile system – services that rehabilitate, educate, and prepare them for successful re-entry into the community, even as they are held securely in a juvenile prison.

If a child is sent to adult prison, he or she faces a far greater risk than adult inmates of sexual assault, violence, and suicide. Since most of the children transferred to adult court in Orleans Parish are back in the community within five years, the district attorney’s office should be deeply concerned about how transfer affects them.

High rates of juvenile transfer also exact a great financial cost. New Orleans is currently spending $7 million to expand the juvenile detention center to hold young people transferred into the adult system – an expansion that would be unnecessary if the district attorney chose to keep more young people in juvenile court, where periods of pretrial detention are much shorter.

The difference in case-processing times means it costs more to detain a child facing transfer to the adult system. When the district attorney attempts to transfer a 14-year- old – the rare exception in which a judge is involved in the decision – that child spends an average of 409 days in pre-trial detention awaiting a transfer hearing, costing New Orleans taxpayers more than $96,000.

Choosing to prosecute a child in the juvenile system, which has a greater likelihood of diverting the child from future crime, can have significant long-term savings. Criminologists estimate that preventing just one adolescent from becoming a serial offender saves society between $2 million and $5 million over a lifetime.

While statistics demonstrate that district attorneys in other parishes often choose to keep transfer-eligible children in juvenile court, the numbers in Orleans Parish tell a very different story. Defense attorneys who negotiate with Cannizzaro’s office also indicate that offering mitigating information about their young clients very rarely results in a decision to keep them in juvenile court.

This default practice of juvenile transfer must end. Adult prosecution must be used sparingly, with consideration of the circumstances surrounding the case and the child, and deliberate thought about which justice system will better deter him from crime.

This report recommends that the district attorney’s office consider a child’s maturity, mental health, delinquency history and prospect for rehabilitation in the juvenile system before sending a child to adult court.

The City Council should create and fund a committee that allows stakeholders in the criminal justice system a process to provide information and expertise to the district attorney’s office when it considers children for adult prosecution. The district attorney’s office should also maintain statistics on its juvenile transfer practices and publicly report them every quarter to ensure transparency and accountability.

Defense attorneys and the accused child’s family members can help make this process successful by working quickly after the child’s arrest to gather records and personal information about the child to provide the district attorney’s office with a basis to keep the child in juvenile court.

The stakes for New Orleans’ children and the safety of the city’s communities couldn’t be higher.

Moving certain children from juvenile court to adult court is not a complicated process under Louisiana law. In the majority of cases, the most important factors under the law are a child’s age and his alleged offense. Very little evidence of a crime needs to be presented by the prosecution before a child can be transferred. Only 14-year-olds receive a hearing in which a judge considers the child’s individual characteristics before ruling on the district attorney’s motion to transfer.

Once a child is transferred to adult court, a judge cannot transfer the child back to juvenile court. While 24 states have a process called “reverse waiver,” allowing for a hearing before an adult court judge to determine the child’s suitability for the adult system, this important safeguard does not exist in Louisiana. Instead, in almost every instance, the law has entrusted the prosecutor with the grave responsibility of determining if a child should be in the adult system. The Orleans Parish district attorney has used his power to transfer children to adult court in the supermajority of cases.

Here is how that process works for children of different ages:

Children who are 14

Children who are 14 and charged with one of a small number of offenses – including murder, first-degree rape, aggravated kidnapping, and armed robbery – can be transferred to adult court only after an evidentiary hearing in juvenile court.

In that hearing, a judge must decide “by clear and convincing proof, [that] there is no substantial opportunity for the child’s rehabilitation” after examining the child’s alleged offense and “whether the protection of the community requires transfer.” The judge also evaluates the child’s maturity and sophistication – both physical and mental – and whether the alleged act might be related to a physical or mental problem. The judge must further consider previous acts of delinquency, past treatment efforts, and rehabilitative resources available to the child in the juvenile system. When a child is transferred under these circumstances it is known as a “judicial waiver” because the judge has waived the juvenile court’s original jurisdiction.

Children who are 15 or 16

A small number of 15- and 16-year-olds are transferred to adult court based solely on their charges. Children charged with murder, first-degree rape or aggravated kidnapping are automatically transferred after a juvenile court judge has found probable cause for arrest or after a grand jury has returned an indictment. When probable cause is found for these offenses, a child is automatically moved to “the appropriate adult facility.” This type of transfer to adult court is known as a “legislative waiver” because the legislature has determined that the specified offenses merit adult prosecution once probable cause is determined.

A greater number of children in this age group are subject to discretionary transfer by the district attorney, who may prosecute 15- or 16-year-olds as adults when they are accused of certain offenses – including armed robbery, attempted murder, and second-degree rape, and second offenses of burglary of an inhabited dwelling and distribution of controlled substances.

Although a juvenile judge holds a probable cause hearing after a child is arrested, that hearing is not a safeguard against the child being needlessly pushed into the adult system. Probable cause is a very low standard of proof – far lower than the proof needed to demonstrate guilt at trial. Moreover, even if the juvenile court judge finds that probable cause for the offense does not exist, a prosecutor may seek a grand jury indictment and transfer the child anyway. A child transferred to adult criminal court under these circumstances has been transferred under what is known as “prosecutorial waiver” because the decision to waive juvenile jurisdiction rests with the prosecutor.

Children who are 17

Children who are 17 are automatically tried as adults for any offense., Louisiana is one of only nine states where 17-year-olds are always adults under criminal law.

Louisiana’s transfer laws have not always been as broad as they are today. During the early 20th century, they included only a few offenses and almost always required an explicit list of findings before transfer could occur. The laws were significantly expanded in the 1990s, largely as a reaction to the media-fueled fear of a coming plague of “juvenile superpredators.”

Despite the now-widespread recognition that the “juvenile superpredator” phenomenon was fiction – as well as the fact that our understanding of children’s brain development has evolved significantly since the 1990s – our transfer laws still represent the reactionary, outmoded political climate that prevailed a quarter century ago.

Narrow origins

Louisiana’s juvenile court system was created in 1906 in recognition of the fact that “that the ordinary process of the criminal law does not provide such treatment and care and moral encouragement as are essential to all children in the formative period of life, but endangers their whole future.”

Children – long defined in Louisiana, for purposes of criminal law, as people under 17 – accused of murder, manslaughter and rape were statutorily exempt from the juvenile system. They were the first to be subject to legislative waiver. Over the next 70 years, the Louisiana Constitution and state laws were amended to include different legislative waiver offenses and to establish a range of ages at which children were subject to automatic transfer to the adult system. The list has always been short, limited mainly to “capital” offenses. Today, offenses carrying a potential life sentence make up the list.

In the 1970s, motivated by a desire to hold some young people accountable through a system that offered more punitive options than the juvenile system, the Louisiana Legislature created judicial waiver. Under this system, after a child was charged in juvenile court, the juvenile court judge could decide whether the case should be adjudicated in juvenile court or transferred to adult criminal court.

By 1980, the judicial waiver process required the court to consider whether there was a “substantial opportunity for rehabilitation through facilities available to the juvenile court.” To make this determination, the juvenile court judge was called upon to consider the age and maturity of the child, the child’s previous offenses, and “such other criteria as the court deems relevant.” This provision required the juvenile judge to decide what mode of prosecution would be the most appropriate given the alleged crime and the child’s circumstances.

‘Juvenile superpredator’ fears and transfer expansion

The scope of transfer laws remained largely the same until the 1990s – the height of the “juvenile superpredator” scare. During this time, a spike in juvenile crime led academics to theorize that a new type of young offender would perpetrate a crippling and violent nationwide crime wave.

In response, policymakers across the country enacted harsh sentencing laws that enabled prosecutors to transfer more children to the adult system. In Louisiana, the minimum qualifying age of judicial waiver was dropped to 14 and the list of offenses eligible for transfer was expanded again. The Legislature also created the first prosecutorial waiver system, allowing prosecutors to charge certain juveniles directly in adult court once a juvenile court judge or a grand jury in adult court found probable cause for their arrest. The list of offenses prosecutors could use to send a 15- or 16-year-old to adult court was long.

This change had an enormous impact. It essentially transferred from judges to prosecutors the decision of whether a child should be prosecuted in adult court. Where the decision to transfer a child to adult court once came after a juvenile court evaluated the child and the charges, it could now occur before the child was even charged in juvenile court. The judicial waiver system was gutted. It now effectively applies only to 14-year-olds.

As legislators debated making these changes, they focused on ensuring that children charged with certain offenses could be transferred to adult criminal court as quickly as possible. To justify the changes, they offered anecdotes of juvenile crime, some originating in other states – or even other countries – as well as the potential for some young adolescents to achieve adult physical maturity long before adult sanctions could be imposed. They also expressed fear that repeat offenders would be undeterred by juvenile punishment.

Legislators did not debate many of the points that are currently thought to be relevant to the unique nature of juvenile crime. None of the policymakers acknowledged that juveniles are more capable of rehabilitation than adults. They didn’t discuss the harm that adult convictions and incarceration can inflict on a young person, or that such penalties can increase the likelihood a young person will reoffend. They also failed to acknowledge the benefit of providing high-risk youth with age-appropriate interventions to deter them from future delinquent behavior.

In the absence of such considerations, the Louisiana Legislature adopted a law that gives prosecutors broad powers to send a child into the adult system without requiring any specific findings about the child beyond his age and offense.

Expanding transfer laws “did not flow from or build on careful research,” observes Dr. Donna Bishop, a professor of criminology and criminal justice and a leading expert on these policies. “Recent research demonstrates convincingly that if changes in transfer policy [in the 1990s] had been contingent on scientific evidence of their efficacy, they would have been rejected.”

Notably, even as the Legislature sought to expand the availability of the adult court to prosecutors, it did not eliminate the option of juvenile court. District attorneys maintained the ability to prosecute a child in the juvenile system even if he was charged with a serious crime.

A new understanding of juvenile transfer

In the decades since these expanded transfer laws were introduced, scientists and the courts have come to recognize that children accused of crimes are more capable of change than adults accused of the same crimes. Children respond to different kinds of interventions than adults and therefore should not automatically be punished in the same way.

Adolescents’ ability to make sound decisions may not solidify until they reach young adulthood because their brains are still developing. The U.S. Supreme Court has indicated that a young person’s capacity for change is a reason not to treat him or her the same as an adult in sentencing. A large body of research now shows prosecuting children as adults damages – rather than improves – public safety.

In recognition of these realities, the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, the Institute of Judicial Administration, American Psychiatric Association, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the Council of Juvenile Correctional Administrators, the National Association of Counties, and the American Bar Association all have declared that transferring juveniles to adult court, especially without consideration of each child’s individual characteristics, is wrong.

Acknowledging that prosecuting juveniles in adult court does not achieve public safety goals, 28 states have taken one or more measures to remove youths from the adult system since 2005.

-

Fourteen states have reformed their transfer laws to reduce the number of youths that end up in the adult system (Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Nevada, Indiana, Utah, Virginia, Washington, Ohio, Maryland, Nebraska, and New Jersey).

-

Twelve states have made changes to their laws that allow age to be considered at sentencing (Florida, California, Colorado, Georgia, Indiana, Texas, Missouri, Ohio, Washington, Hawaii, West Virginia, and Iowa).

-

Eleven states have enacted laws limiting the detention of youths in adult jails (Texas, Colorado, Idaho, Indiana, Maine, Nevada, Hawaii, Virginia, Pennsylvania, Oregon, and Ohio).

-

Five states have raised the age of criminal majority, increasing the number of young people eligible to stay in juvenile court (Mississippi, Connecticut, Illinois, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire).

Louisiana has not made any such changes.

Before 2009, the use of juvenile transfer in Orleans Parish was rare. However, since Leon Cannizzaro became district attorney in 2009, his administration has used juvenile transfer with an alarming frequency. He has prosecuted 200 children in adult court. Nine more are detained and awaiting a transfer decision at the time of the writing of this report. Between 2011 and 2014, the district attorney’s office prosecuted 83 percent of eligible 15- and 16-year-olds in adult court.

By contrast, when the district attorney’s office has had to seek judicial waiver for 14-year-olds accused of serious offenses a judge has approved that transfer only once since 2011. It’s reasonable to question, therefore, just how many 15- and 16-year-olds would have been transferred if those children’s individual characteristics had been examined by a neutral party.

Orleans Parish is an outlier in its default use of juvenile transfer. District attorneys of other Louisiana parishes with large urban populations use juvenile transfer only in a minority of cases. From 2010 to 2013, Orleans Parish transferred almost five times as many children as East Baton Rouge – a larger parish where more armed robberies occur per year. Caddo Parish has the highest rate of transferred youth after Orleans but still transfers only 39 percent of its eligible cases – less than half the percentage Orleans transfers. Jefferson Parish only transferred 22 percent of transfer-eligible cases in 2013 and 2014.

The outcomes of the district attorney’s transferred cases demonstrate that his default practice of juvenile transfer is neither necessary nor practical. Thirteen percent – more than 1 in 8 – of New Orleans’ transferred children are found not guilty, have their charges dismissed, or are found to be incompetent and legally ineligible to be prosecuted. These young people never should have been prosecuted at all, let alone subjected to adult criminal court or detained in Orleans Parish Prison.

^ 60% of transferred youths were

not convicted or received a sentence of

5 years or less.

Nearly 40 percent of New Orleans’ transferred children return to the community immediately after their cases are resolved – either because they are not convicted or do not receive a prison sentence. Twenty-seven percent receive credit for time served or probation. This trend undermines the District Attorney’s claims that transfer is necessary to protect the public – children who are too dangerous to be in the community would not be permitted to plead to a probated sentence.

^ Young people have been shown

overwhelmingly to accept plea

deals,even when they are

innocent to avoid the risk of

rial and longer adult sentences.

Nearly half of New Orleans’ transferred children (47 percent) have received the same sentences they could have received in the juvenile system. These are sentences of five years or less in the Department of Corrections, credit for time served, or probation. If these sentences had been imposed in the juvenile system, they would have been accompanied by age-appropriate rehabilitative services, education and psychological treatment. But none of these services are provided in the adult system, which means these young people emerge from adult facilities as convicted felons without the benefit of programs or developmental opportunities that can help them succeed when they return to the community.

Although 87 percent of New Orleans’ transferred children are convicted of some offense in criminal court, this statistic is misleading without context. Ninety-six percent of these convictions come from guilty pleas. Young people have been shown overwhelmingly to accept plea deals, even when they are innocent, to avoid the risk of trial and longer adult sentences.

^ Most youths plead to offenses that

would not have been transferrable.

Seventy-five percent of transferred youths who plead guilty plead to lesser offenses – most of which would not have been transferrable – including nonviolent offenses and even misdemeanors. In some cases, the charges pled to may be more accurate descriptions of conduct of which the young defendant was actually guilty – and where these charges were not eligible for transfer, this trend is particularly troubling. In others, especially with offers of pleas to nonviolent or misdemeanor charges, these pleas may indicate weak evidence of guilt of any offense.

The broad power granted to the district attorney throughout this process – from the decision to transfer a child to the length of a sentence received for pleas – must be wielded with extreme caution and deliberation. Since a judge will never evaluate most of these children to determine if they should be tried in the adult system, it is the ethical responsibility of the prosecutor to make specific inquiries into whether each child and the public would best be served by the juvenile system.

Despite evidence to the contrary, the district attorney has remained adamant that his use of default juvenile transfer is prudent. He cites “1,000 armed robberies a year” in New Orleans as a reason he transfers so many young people, without offering any proof that juveniles are connected to more than a few of those offenses or demonstrating that his approach to juvenile transfer has made the city safer. It hasn’t. Arrests for transfer-eligible offenses have increased during Cannizzaro’s time in office.

Statements he has made publicly, and those of defense attorneys whose young clients are prosecuted by his office, reveal that Cannizzaro’s approach is not a deliberate, individualized evaluation of children but rather one where transfer is the default outcome.

Cannizzaro recently informed the City Council that he considers two major factors when it comes to juvenile transfer: whether the child has had previous contact with the juvenile justice system, and what the alleged victim of the crime wants to happen in the case. But a closer examination of the children transferred suggests that only a minority have previous contact with the juvenile justice system.

^ Arrests for transfer-eligible offenses

have increased during Cannizzaro’s time in office.

Moreover, information beyond delinquency history and the wishes of the victim are relevant to a transfer decision. While the law does not make this information immediately available to a district attorney, Cannizzaro’s office has consistently made clear to defense attorneys that mitigating characteristics of their clients are not weighty factors in the transfer decision – even when that information is offered. Cannizzaro’s decision to transfer more than 80 percent of eligible 15- and 16-year-olds charged with certain offenses demonstrates that his inclination is to transfer children without much consideration of factors beyond the criminal allegation.

Cannizzaro’s pattern of transfer shows delinquency history is not a significant factor in transfer decisions.

Out of 107 cases of transferred children for which delinquency history was available to this report’s authors, 39 had no previous contact with the juvenile justice system, and another 19 had only one nonviolent instance of contact with the juvenile system. In other words, nearly 60 percent of the children transferred had either no or minimal delinquency history.

Corroborating this numerical evidence is Cannizzaro’s refusal to commit to the City Council not to transfer certain children: those with nonviolent offenses, those who are incompetent, or those who have no criminal record. The American Psychiatric Association explicitly calls for the prohibition of such transfers.

Cannizzaro’s remarks to The New Orleans Advocate in March 2015 also confirm that default transfer is his standard practice. He stated that for any armed robbery allegation, “adjudication in Criminal District Court is more appropriate.” Ultimately, all that is important to the district attorney is the alleged crime. When making a transfer decision, “[w]e look at the subjective evidence of the risk they pose ... based upon the acts of which they stand accused.”

This approach is completely out of step with the recommendations of the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges – a widely respected national group whose mission is to “provide all judges, courts, and related agencies handling juvenile, family, and domestic violence cases with the knowledge to improve the lives of the families and children who seek justice.” The Council has affirmed that “transfer and waiver decisions should only be made on an individual, case-by-case basis, and not on the basis of the statute allegedly violated. . . . [Waiver decisions] should be rare and only [occur] after a very thoroughly considered process.”

The district attorney does not appear to value information about the individual child in making transfer decisions

Defense attorneys who have attempted negotiations to keep their clients in juvenile court agree that transfer appears to be the default – if not the universal – practice of the district attorney’s office. These attorneys report that they regularly have offered information to the office about their clients that a judge would find relevant to a transfer decision – a disability, severe trauma, psychiatric medications taken by the child, a minor role in the alleged offense, a lack of previous contact with the justice system – but that information very rarely prevents the district attorney’s office from sending a child into adult court.

Cannizzaro’s default approach to juvenile transfer conflicts with the National District Attorneys Association’s National Prosecution Standards. These standards insist that “the screening decisions [about whether to prosecute a person and for what] are the most important made by prosecutors in the exercise of their discretion in the search for justice.”

The standards lay out 13 relevant considerations in screening, which include “the characteristics of the accused that are relevant to his or her blameworthiness or responsibility ... the defendant’s relative level of culpability in the criminal activity ... [and] any other aggravating or mitigating circumstances,” such as the maturity, mental health, and personal circumstance of the defendant.

Quite simply, it is an abdication of a district attorney’s ethical responsibility to fail to consider the child’s circumstances that may have led him or her to be arrested. A district attorney should be concerned with the same facts about a child as a judge making a decision to transfer. If this information is not independently available to a district attorney, he should solicit it from the defense attorney. At the very least, when it is presented to him, he should seriously consider it. Cannizzaro’s practices make clear that he does not take this approach.

The district attorney must balance society’s interests

Cannizzaro has repeatedly said that his decision to transfer youths accused of transfer-eligible offenses is motivated by the desires of victims to whom he feels accountable. While a district attorney should take the desires of victims into consideration, it is a violation of prosecutorial ethics to allow victims to dictate prosecutorial decisions.

As the National District Attorneys Association has explained, “a prosecutor does not represent individuals or entities, but society as a whole. In that capacity, a prosecutor must exercise independent judgment in reaching decisions, while taking into account the interest of victims, witnesses, law enforcement officers, suspects, defendants and those members of society who have no direct interest in a particular case, but who are nonetheless affected by its outcome.”

By failing to objectively consider what approach to prosecuting a child will balance the interests of all of those entities, the district attorney ignores his responsibilities as the city’s chief elected law enforcement officer.

Cannizzaro’s statements demonstrate that he is out of touch with the community he serves and indifferent to the standards and best practices of his profession.

The district attorney claims that children arrested for serious offenses in New Orleans have been given every chance to succeed, demonstrating a disconnection from the community he serves

The district attorney has said, “It is the job and purpose of a juvenile’s family, community, church, school, and psychologist to prevent the individual from resorting to violent crime. The district attorney’s office comes to the table when these institutions have already failed.”

His attitude is dangerously out of touch with the reality of New Orleans, where 39 percent of children live in poverty. Many of the children accused of serious crimes don’t have access to any of the resources that Cannizzaro presumes are at their disposal. And, as discussed above, many of the children he transfers have had no previous contact with the juvenile system or any other system that might have provided therapeutic or rehabilitative services.

By focusing on the failure of families, service providers and religious leaders to prevent crime, Cannizzaro is missing an opportunity and a responsibility to intervene on behalf of children who are at a crossroads. This intervention is the express purpose of the juvenile justice system. The district attorney’s abdication of responsibility is especially troublesome given that all but one of the children he has sent into the adult system are black, because research has proven that children in this demographic are wrongly perceived as more adult, more responsible for their actions, and are more easily dehumanized than white children.

The district attorney’s attitude toward juvenile transfer ignores the science of adolescent development and wrongly presumes that public safety and rehabilitation are mutually exclusive goals.

Cannizzaro has said that his reason for treating transfer-eligible children as adults is that “their lack of higher order decision-making skills” makes them “dangerous” and therefore more deserving of harsh punishment. “These offenders are far more impulsive and far less concerned about the consequences of their decisions on others,” making them appropriate for adult treatment, he told the Advocate.

But this outmoded attitude is in direct conflict with U.S. Supreme Court case law, scientific research and the philosophy that justifies the need for a juvenile justice system. To the extent that impulsivity significantly contributes to criminal behavior in young people, fundamental fairness requires that their youthfulness be considered in determining the punishment they deserve.

Cannizzaro also misunderstands the trajectory of young people accused of serious offenses. Research shows that most adolescents, even those who commit serious offenses, outgrow criminal behavior as they transition to adulthood. While accountability is vital in teaching young people to behave within the bounds of the law, treating them as adults and as the “worst of the worst” ignores the fact that their illegal behavior is likely to stop as they grow up, whether through active rehabilitation or simply maturity gained through age.

Default juvenile transfer endangers public safety by encouraging recidivism

Despite the district attorney’s claims that concerns for public safety motivate his transfer practices, experts assert that public safety is not served by transferring a lot of children to adult court. “To run transfer as a program to achieve crime-control objectives, it’s a mistake,” said Columbia Law School Professor Jeffrey Fagan, a renowned authority on adolescent crime. “It actually does more harm than good.”

No studies in New Orleans have compared rates of recidivism for transferred youth with eligible youth who were not transferred. The authors of this report were unable to obtain the data necessary for such a study. However, a 2016 report by the Institute for Public Health and Justice at Louisiana State University found that young people sentenced to Louisiana’s adult criminal system at age 17 appeared to recidivate at a 20 percent greater rate than those arrested as juveniles and sentenced to the state’s juvenile justice system at 17. Research from across the country published over the last decade also overwhelmingly shows that juvenile transfer does not stem crime and actually increases it in some cases.

State and national studies demonstrate juvenile transfer tends to increase recidivism

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) sponsored an independent review of all of the studies related to youth transfer to the adult system. Its 2007 report found that transfer increases violence, causes harm to young people and threatens public safety.

The CDC’s review examined every study on transfer policies that had been published in an academic journal or conducted by a government agency and compared outcomes for children in the juvenile system with those transferred to the adult system. The studies compared children charged with similar offenses and with similar background characteristics.

The CDC’s review concluded that four of the six studies “found an undesirable effect in which transferred juveniles committed more subsequent violent or general crime than retained juveniles.” One study indicated that transfer did not reduce recidivism any better than the juvenile system.

Overall, the studies showed a relative 34 percent increase in subsequent crimes for transferred youths. The CDC task force recommended “against laws or policies facilitating the transfer of juveniles from the juvenile to the adult judicial system.” It found that “to the extent that transfer policies are implemented to reduce violent or other criminal behavior, available evidence indicates that they do more harm than good,” and that “the use of transfer laws and strengthened transfer policies is counterproductive to reducing juvenile violence and enhancing public safety.”

A subsequent report by the U.S. Department of Justice Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention mirrored the CDC’s findings. The 2010 report concluded that transfer laws have little or no specific deterrent effect. The report cited six major studies showing that youths convicted in criminal court have higher recidivism rates than their counterparts in juvenile court.

Studies from several states also show that default juvenile transfer practices do not deter young people from running afoul of the law again – and even increase those chances. These studies provide no reason to suspect that such policies have a different outcome in Orleans Parish.

The Illinois-based Juvenile Justice Initiative highlighted in a 2014 report the findings of several Illinois studies conducted after the state’s “automatic transfer” laws were enacted in 1982. The laws expanded the scope of criminal jurisdiction to include children under the age of 17 charged with certain crimes. These children were automatically charged in the criminal system without regard for the child’s circumstances.

The report’s review of the various studies found that pushing young people into the adult system without any examination of their individual qualities failed to control serious juvenile crime. A 1988 study by the Chicago Law Enforcement Study Group, which sought to evaluate the impact of the Illinois “automatic transfer” laws, concluded that they had not decreased juvenile offending.

The Illinois Supreme Court Special Commission on the Administration of Justice also found that from the early 1980s to the early 1990s, as the number of juveniles tried in adult court increased, no deterrent effects increased along with it. It recommended that the Illinois Legislature consider changes to the transfer statutes. The legislature responded with changes to the law in 2005.

An inquiry in California reached similar conclusions. That state passed Proposition 21 in 2000, which provided for the transfer of juveniles into the adult system by prosecutors. The Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice studied the practices of prosecutors throughout the state from 2003 to 2010 to determine whether the use of this power increased.

The study, which analyzed data from the 35 California counties that make up 97 percent of prosecutorial waiver cases, found that there was an inconsistent use of this power across the counties, producing mixed results. Thirteen percent of all such cases came out of Orange County, but this county saw an increase in juvenile felony arrests. In San Francisco, however, where only seven cases were transferred, there was a decrease in juvenile felony arrests. The researchers determined that there was no relation between the use of this power and a reduction in youth crime. Moreover, from 2003 to 2012, there was no evidence of any additional safety benefit as a result of Proposition 21.

The Washington State Institute for Public Policy also examined practices in Washington, a state where more than 1,300 youths have been processed in the adult system since 1994 – the year the state legislature enacted an “automatic decline” law. Under the law, certain juvenile cases are automatically “declined” by juvenile court and transferred to criminal court.

In a 2013 report the Institute compared the recidivism rates of youths “automatically declined” after 1994 with the recidivism rates of youths, pre-1994, who would have been eligible under the law. Researchers studied the youths for 36 months after their sanctions. The results showed that the “automatic decline” group had higher recidivism rates than that of the pre-1994 group.

These studies show that the adult prosecution of children does not decrease recidivism, but instead tends to increase the likelihood of young people reoffending. This should not surprise us. Youths convicted criminally are unable to access most or all youth-focused rehabilitative programs, treatments and re-entry resources that help children succeed as they mature into adulthood. They are also exposed to adult offenders in prison from whom they are likely to learn criminal behaviors. The punitive adult criminal justice system doesn’t scare kids into good behavior. It fundamentally undermines the possibility that they will ever become stable and productive.

Adult convictions set young people up to fail again

Once they return to their families and communities, young people with adult convictions find immediate obstacles to achieving stability. Youth who have been involved with the adult criminal justice system often lack important vocational and job-readiness skills necessary to secure and maintain employment. For young adults, these deficits are particularly acute. They have few vocational skills and most have little or no job experience, making it even more difficult to find and retain employment.

Housing can be another challenge. The Housing Authority of New Orleans broadly denies housing to any person who has a criminal record “involving drug related, violent or other criminal activity which present [sic] a threat to the health, safety, or right to peaceful enjoyment of the premises by other residents.” A convicted person may also be permanently excluded from even visiting a friend or family member living in public housing. Predictably, homelessness is a frequent consequence of an adult conviction, which only puts young people at a greater risk of another encounter with the justice system.

Adult convictions also can undermine eligibility for student loans and employment. In Louisiana, people with criminal convictions may not obtain student loans from the Louisiana Office of Student Financial Assistance. A felony record limits the eligibility of ex-offenders for certain jobs, such as employment in Louisiana’s oil and gas, shipping and chemical industries. Workers in this industry must have a Transportation Worker Identification Credential (TWIC card), but people are barred from applying for a TWIC card for seven years after some convictions.

Some licensing boards won’t issue licenses to people with adult convictions, which also makes it difficult for young people with adult records to obtain jobs. Furthermore, adult arrests and convictions are public records and must be disclosed if requested by potential employers, which may prevent youths from obtaining employment in any field – making it more likely they will recidivate. Unemployed ex-offenders are three times more likely to reoffend than employed ex-offenders.

With so many of New Orleans’ children returning to our communities after an adult conviction while they are still young, we have a vested interest in their success after release. The district attorney should always consider how to achieve the best outcome for all New Orleanians when deciding whether to prosecute children criminally or in the juvenile system.

Default juvenile transfer wastes taxpayer dollars

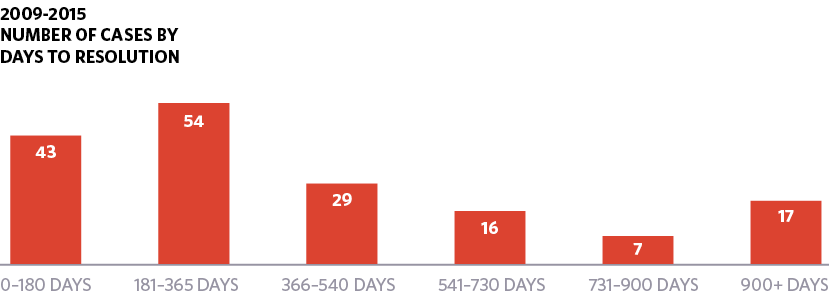

The district attorney’s use of default transfer has come at great expense to taxpayers. It costs more to detain children being tried as adults than those facing the same charges in the juvenile system, because they are held before trial for much longer in the adult system. In Louisiana, children detained while awaiting trial in juvenile court cannot be held for longer than 60 days. The adult system, however, allows for up to two years – 730 days – to bring a case to trial.

In Orleans Parish, the average period of pretrial detention for all children being tried as adults is 414 days. That’s more than a year of taxpayer-provided food, housing and medical expenses. This expense becomes even more questionable when one considers that 14-year-olds in Orleans Parish awaiting a transfer hearing spend such a long time in pretrial detention yet are almost never transferred. At the cost of approximately $236 per day, a 14-year-old detained in the Youth Study Center awaiting an unlikely transfer costs taxpayers an average of $96,524. Of the 14-year-olds currently being detained, only one is charged with a homicide.

There is yet another cost associated with juvenile transfer in New Orleans – the cost of construction. The district attorney’s default transfer practice has pushed New Orleans to commit $7 million dollars to expand the juvenile detention facility, a facility that wouldn’t be necessary if the same children were prosecuted in the juvenile system. That system’s faster case-processing time would have meant that the original Youth Study Center could have accommodated them.

Criminologists also have determined that preventing just a single adolescent from becoming a serial offender saves society between $2 million and $5 million in “victim costs, criminal justice costs (police, courts, and prisons), and lost productivity of offenders who are incarcerated.” Under the current practices of the district attorney’s office, New Orleans taxpayers could be expected to foot that bill as well.

Default transfer ignores scientific truths about children

The District Attorney’s practice overlooks fundamental realities about young people that science and the law recognize as fact. As outlined above, a youth’s brain is physiologically different than an adult brain.

Young people have a significantly higher capacity for rehabilitation than adults, which must be a factor in decisions about their prosecution. Prosecuting children as adults, particularly without examination of their individual characteristics, ignores this reality. In a system of default juvenile transfer, where mitigating factors affecting these youth are ignored, unjust outcomes are inevitable.

The district attorney’s use of default transfer ignores the following truths:

Adolescents’ capacity to change

Recent research shows adolescents think differently than adults. While a person’s intelligence and ability to reason is largely set by age 16, a person’s ability to make decisions in emotionally charged moments is heavily affected by short-sightedness, impulsiveness and peer influence well into early adulthood.

These differences were acknowledged by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2005, when it found that executing people convicted of crimes committed before they were 18 is unconstitutionally cruel and unusual. Roper v. Simmons identified three significant differences between children and adults relevant to their culpability. First, “[a] lack of maturity and an underdeveloped sense of responsibility are found in youth more often than in adults and are more understandable among the young. These qualities often result in impetuous and ill-considered actions and decisions.”

Second, “[j]uveniles are more vulnerable or susceptible to negative influences and outside pressures, including peer pressure.” Finally, “[t]he character of a juvenile is not as well formed as that of an adult. The personality traits of juveniles are more transitory, less fixed.” These differences, the court summarized, “render suspect any conclusion that a juvenile falls among the worst offenders.”

The court later expanded its reasoning, in Graham v. Florida, to juveniles charged with non-homicide offenses, holding that they could not be given a sentence of life without parole. Most recently, the court held that a life sentence could not be imposed on a person convicted of a homicide committed before he or she was 18 without a hearing to address the individual characteristics of the convicted person. “Because juveniles have diminished culpability and greater prospects for reform,” the court declared in Miller v. Alabama, “they are less deserving of the most severe punishments.”

Variations in culpability

Given the nature of adolescent brains, a young person who commits a serious offense is less culpable than an adult who commits the same offense. Juveniles also tend to offend in groups, rather than as individuals, at much higher rates than adults. Group offending has even been called an “essential feature” of juvenile crime. This tendency reflects their greater susceptibility to peer pressure and poor decision-making.

Yet under Louisiana law, a young person can be arrested and held equally accountable for an offense like armed robbery even if someone else in the group of arrestees was the one with the gun. The law therefore allows young people who may not have had serious involvement in a crime to be transferred into the adult system. This is especially troubling given the district attorney’s practice of default transfer.

The connection between trauma and arrest

Default juvenile transfer does not take into account the prevalence of trauma in young people who have been arrested and the role that trauma can play in causing criminal behavior. As much as 80 percent of young people who have been arrested report exposure to at least one traumatic incident. The majority report having been exposed to multiple types of trauma. Post-traumatic stress disorder is prevalent in justice-involved youth.

Trauma is pervasive among children in New Orleans. In a recent survey of black adolescents in New Orleans, 39 percent reported that they had witnessed domestic violence, 20 percent reported post-traumatic stress disorder and suicidal thoughts, 17 percent worried about not having enough food or adequate housing, and 30 percent worried that they are not loved.

With these kinds of statistics in mind, the U.S. Attorney General’s Task Force on Children Exposed to Violence explicitly declared that “[l]aws and regulations prosecuting [juveniles] as adults in adult courts, incarcerating them as adults, and sentencing them to harsh punishments … must be replaced or abandoned.”

Developmental immaturity and mental illness

Transferring juveniles to adult court without any inquiry into their developmental maturity ignores the fact that adolescents have a lower capability to understand and participate in legal proceedings against them, undermining the fairness of the justice process. Unlike proceedings in juvenile court, proceedings in adult criminal court are not tailored to a young person’s level of understanding, nor managed by professionals familiar with juvenile needs, comprehension and communication abilities.

Developmental immaturity can impede a young defendant’s ability to make decisions in his or her best interest during the criminal process. For example, adolescents accused of committing a crime with co-defendants may be influenced by a desire for peer approval when determining trial strategy, particularly when deciding whether to indicate that a co-defendant was more criminally responsible.

Adolescents may have difficulty assisting their attorneys because court procedures can lead children to believe that the judge, prosecutor and defense attorney are all on the same side (against the adolescent). In fact, research indicates that many children believe their attorneys will share private information with the judge or police, and that their rights are revocable by adults involved in the proceedings (such as the police, prosecutor or judge). As a result, they may choose not to share information with their attorneys – even if it could help their cases.

Children may also be at a disadvantage in the plea bargaining process in criminal court. This is deeply significant in New Orleans because 96 percent of transferred children who are convicted plead guilty. The characteristic failure of adolescents to anticipate future consequences may make young defendants more likely to accept plea deals, even if they have a chance of a better outcome at a trial. They are likely to focus on a plea deal’s short-term benefits (avoiding trial, getting out of pre-trial detention, avoiding a maximum sentence regardless of the strength of the evidence) rather than its possible long-term consequences (a criminal record, incarceration in an adult facility, the responsibilities and restrictions of probation or parole).

While in many states the competency evaluation process would protect a developmentally immature child against prosecution in adult court, Louisiana’s competency laws only allow for a child with a “mental illness or developmental disability,” to be found incompetent. Even children found to be at such a disadvantage are not fully protected from transfer: State law allows district attorneys to transfer a child to adult court even after the child’s attorney has asked the juvenile court to examine the child’s competence to stand trial.

Remarkably, the Orleans Parish district attorney has refused to promise to halt the transfer of youths once the possibility of incompetency is raised in juvenile court. In fact, Cannizzaro declared to the City Council that he would charge as adults children who were legally incompetent to stand trial.

Putting children in the adult correctional system doesn’t prepare them to re-enter society

The New Orleans City Council, to its credit, has resolved to remove all children in Orleans Parish currently housed in pre-trial detention facilities shared with adults. Those plans, however, will not be fully implemented until 2018. Meanwhile, unless current practices change, the district attorney’s office will continue to seek to transfer children, some of whom will be detained in Orleans Parish Prison for months – if not years.

Regardless of where they are held before trial, many of New Orleans’ transferred youth will end up in adult prisons. Because the experience of being imprisoned in the adult correctional system can make it even more difficult for children to re-enter society, the district attorney’s failure to carefully consider whether children can be better served in the juvenile system is also dangerous and counterproductive.

Adult correctional facilities endanger young people

Children in adult facilities face significant dangers due to their status as minors and their physical vulnerability. The risk of sexual assault for children in adult facilities is five times greater than it is for children in juvenile detention.

Research has also found that while children under 18 were just 1 percent of the prison population in 2005 and 2006, they accounted for 21 percent and 13 percent of the victims of inmate-on-inmate sexual violence in jails in those years, respectively. They are also twice as likely as young people in juvenile detention to be physically assaulted by staff. They are eight times as likely to commit suicide as those detained in juvenile facilities.

The view that adult institutions endanger children is endorsed by the American Jail Association; American Psychiatric Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics; the National Association of Counties; the American Bar Association; and the National Commission on Correctional Healthcare, all of which oppose holding juveniles in adult facilities.

The adult correctional system negatively influences youth and harms development

Beyond dangers to their physical safety, children are vulnerable to the negative influences that surround them in adult facilities. They are “likely to learn social rules and norms that legitimate domination, exploitation, and retaliation.” A young person who spends his transition to adulthood in a prison with adult inmates misses critical developmental opportunities – including the assumption of adult social roles, improving one’s prospects for employment and seeking financial stability through work and education. These factors contribute to an overall mortality rate for people who were transferred to the adult system as teens that is nearly 50 percent higher than for people who were prosecuted in the juvenile system.

Louisiana’s adult facilities do not set children up to succeed

The U.S. Department of Justice Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention recently found that “transferred youth sentenced to prison have not only greater needs for behavioral rehabilitation to address disruptive behavior and substance use disorders than transferred youth who receive less severe sentences but also greater needs for psychiatric treatment of major affective and anxiety disorders.” But access to resources necessary to address these needs is minimal in the adult system.

The Research Network on Transitions to Adulthood describes programs that reduce recidivism as programs that emphasize “interpersonal skill-building and cognitive-behavioral counseling. Such programs develop positive social patterns of reasoning by maintaining a focus on managing anger, assuming personal responsibility, taking an empathetic perspective, solving programs, setting goals, and acquiring life skills.”

Yet Louisiana Department of Corrections (DOC) programming is largely focused on vocational training and GED programs. These programs have not been shown to be effective interventions in criminal behavior, especially for youths with serious offenses. Furthermore, the DOC’s programs have a limited capacity, and only half of Louisiana’s state inmates are housed in DOC facilities at all; the other half held in parish jails where programming is often nonexistent.

The DOC has a “youthful offender program” at Dixon Correctional Facility in Jackson. It offers some age-appropriate programming to youth under 19, but the program has significant limitations. It does not comply with federal laws that require “sight and sound” separation of children under 18 from older inmates. Young people housed there have reported arbitrary and violent disciplinary tactics. These tactics include the use of pepper spray and segregated placement in a cell block on the main compound with adults in plain sight. When they are held in these cells, youth receive no programming at all. Children are frequently ejected from the program, and completion rates are exceedingly low.

Effective juvenile justice systems do not coddle young offenders. They maintain facilities with the capacity to safely house children convicted of violent offenses. They rely on evidence-based practices to effectively encourage positive behavior and prevent recidivism while teaching accountability for one’s actions. They also produce better outcomes for children, their families and the community than the adult system.

Louisiana’s Office of Juvenile Justice (OJJ) is better-suited to address the needs of serious young offenders. Louisiana’s juvenile prisons – known as “secure care” facilities – are made of cement and surrounded by barbed wire, just like adult prisons. Sentencing schemes in the juvenile system are similar to those in the adult system. Serious, violent offenses require incarceration in juvenile facilities just as they do in the Department of Corrections. In the juvenile system, young people may be incarcerated until their 21st birthdays, which could mean years in prison for some.

Unlike the DOC, the Office of Juvenile Justice is explicitly bound to “protect the public by providing safe and effective individualized services to youth, who will become productive, law-abiding citizens.” It uses treatment techniques known to result in the most successful outcomes: smaller facilities, keeping young people closer to their homes, and following a model of programming called the Louisiana Model for Secure Care, or LAMOD.

This model, based on the nationally recognized model of youth corrections from Missouri, “focuses on a therapeutic, child-centered environment versus a traditional adult correctional/custodial model.” It places an emphasis on “relationship-building that affords youth the opportunity to belong and contribute to a group, make meaningful choices, develop transferable skills and mentor their peers.” While in custody, young people take part in group therapy. The staff, who are arranged in teams, conduct regular meetings to “discuss progress and ways to support the youth.”

OJJ’s juvenile probation and parole department is charged with helping young people succeed when they return to their communities. OJJ officers are responsible for fulfilling more than 40 functions, including collecting health and school records; developing an individual services plan; building a relationship with the youth’s family; coordinating educational, vocational, and health-related services the youth needs; and “serv[ing] as the link between home, community, school and the juvenile justice system.”

In contrast, a DOC probation and parole officer monitors the probationer’s behavior, enforces the rules and laws against her, and ensures she is returned to custody if she violates those rules or laws. A child whose supervisor is dedicated to helping him or her navigate life outside the system is far more likely to succeed than a child whose supervisor is simply waiting to lock him up again.

There are additional advantages to supervising children through the juvenile system. Children in that system are entitled to representation by attorneys while they serve their sentences – the “post-disposition” phase of the case; children processed through the adult system are not. Attorneys in the post-disposition phase can ensure the OJJ is providing court-ordered services and that children are making progress in custody.

Juvenile judges also maintain jurisdiction over cases while children are in the post-disposition phase. This means they can ensure the programming and duration of the sentences are tailored to the needs of the children and the interests of public safety – the kind of vital attention to each individual person that does not happen for children in the adult system.

As this report has illustrated, the Orleans Parish district attorney has adopted an expensive, ineffective, and misguided practice of default juvenile transfer that has pushed far too many children into the adult justice system. He has prosecuted children as adults without evidence that it makes our communities safer or will help children to contribute positively to society.

In fact, all available evidence indicates that default juvenile transfer has the opposite effect.

As a result of adult prosecution, many young people have lost opportunities that could help them get their lives on a productive course. Those who return to the community are far less likely to avoid reoffending. They’re casualties of an adult justice system that was never intended to rehabilitate a young person who has made a mistake. The district attorney must end the practice of routinely sending young people to adult court without real inquiry into whether it is the right decision for the child.

The following recommendations are intended to ensure reasonable, just and effective prosecution policies for children eligible for adult prosecution in Orleans Parish.

For the New Orleans District Attorney:

Evaluate cases for transfer according to specific criteria

The district attorney’s office should always consider:

-

The age, mental and physical maturity, and sophistication of the child.

-

The nature and seriousness of the alleged offense to the community and whether the protection of the community requires transfer.

-

The child’s prior acts of delinquency, if any, and their nature and seriousness.

-

Past efforts at rehabilitation and treatment, if any, and the child’s response.

-

Whether the child’s behavior might be related to physical or mental problems.

-

Techniques, programs, personnel, and facilities available to the juvenile court which might be competent to deal with the child’s particular problems.

These findings – the same ones that judges in transfer hearings are legally required to make – are central to a transfer decision, whether it is made by a judge or by a prosecutor.

While the law in Louisiana does not create a formal opportunity to present all of the relevant individual circumstances of each transfer-eligible child, as the law in other states does, the district attorney should always give this information due weight when it is presented to him by assistant district attorneys, defense attorneys or other concerned parties.

If, according to these factors, there appears to be a reasonable opportunity for rehabilitation in the juvenile system, the district attorney should not transfer the child.

Nonviolent offenders, first-time offenders and children who are incompetent or whose competency has been called into question should never be transferred to adult court. The district attorney’s office should not attempt to transfer 14-year-olds except in the most extraordinary cases – and never in cases that do not involve homicide.

Collect outcome data and make it easily accessible to the public

The district attorney and the public have a vested interest in the outcome of the cases his office prosecutes. Prosecutors and the public would benefit from access to data about New Orleans’ transfer-eligible young people and the public safety consequences of the decision where to prosecute them.

The district attorney should collect and track information about the children he decides to transfer as well as the transfer-eligible children he prosecutes in juvenile court. For each transfer-eligible youth the office elects to prosecute, the following information should be retained and made available to the public:

-

The youth’s age, gender and race;

-

Whether the youth was ultimately transferred;

-

Offense for which the youth was arrested;

-

Offense with which the youth was charged;

-

Offense for which the youth was convicted (or, in juvenile court, adjudicated delinquent), and whether that conviction is the result of a plea or a trial;

-

If the youth was not convicted (or adjudicated), whether he was found not guilty, incompetent, or his charges were dismissed or refused;

-

If the youth was convicted (or adjudicated), the sentence imposed; and,

-

Information about the youth’s prior and subsequent arrests or convictions, if any.

Be an advocate for Louisiana’s juvenile justice system

A prosecutor should view the juvenile justice system as an important tool in the fair administration of justice. The juvenile justice system works best when the prosecutor supports its methods and goals. The district attorney for Orleans Parish has substantial influence with state government entities to ensure that the resources necessary to help him effectively prosecute children through the juvenile system are available. The district attorney should encourage the Office of Juvenile Justice, the Louisiana Juvenile Detention Association, and the Legislature to do everything possible to serve children in the juvenile system well and ensure they emerge ready to succeed.

For the New Orleans City Council:

Require accountability from the district attorney’s office for juvenile transfer policies

As the elected body that controls the allocation of tax dollars in New Orleans, the City Council should demand that the district attorney’s policies are effective and reflect the community’s values. It should adopt a resolution requiring this district attorney to be more judicious in his use of juvenile transfer.

The resolution should call for specific criteria to be considered in a transfer decision; recommend the transfer of fewer children to adult court; and call for an end to the transfer of children charged with nonviolent offenses, those without any criminal history, or those whose competency is questioned. The Council should require the district attorney’s office to report detailed information about transfer decisions and be prepared to account for its decision-making process.

Create a committee to ensure sound transfer decisions

The Council can help ensure that the district attorney’s office has as much information as possible to make sound transfer decisions. The Council should fill the gap in state law that does not require a formal hearing by funding the creation of a Juvenile Transfer Committee to promote cooperation between the district attorney’s office, child welfare advocates, and representatives of the juvenile and criminal justice systems. Committee members will convene privately, under an agreement of confidentiality, to provide the district attorney’s office with critical expertise and information about the children who may be transferred to adult court.

Recommended committee members include an assistant district attorney, a current or former juvenile judge who will not otherwise review the child’s case, a current or former adult court judge who will not otherwise review the child’s case, a board-certified child psychologist, an expert on juvenile risk and recidivism, a juvenile mitigation specialist, and the defense attorney representing the child in question. The defense attorney should be relied upon, with the client’s permission, to present information relevant for evaluation by the task force.

As each transfer arises, committee members should review materials about each child and make recommendations to the district attorney about that child’s case. The committee should be required to report its activities to the Council annually while keeping identifying information about the children confidential.

For Defense Attorneys:

Gather records and other information early

Defense attorneys and their client advocates are well positioned to help the district attorney make the decision to keep a child in juvenile court. They should make their best effort to collect medical and school records and gather any relevant personal information from clients as soon as possible after arrest. This practice will help ensure that defense attorneys are armed with valuable information when negotiating for their clients to stay in juvenile court.

For Families of Children Facing Transfer:

Assist the defense team with putting together a full picture of the child

The defense attorney is likely to be the person communicating directly with the screening district attorney about the child. But family members of the arrested child can also play an important role in whether their loved one is transferred to adult court. Families can assist defense attorneys in gathering records and can also offer to the attorney valuable personal information about the child that might affect the decision to transfer.

Family members can also collect letters of support for the child from teachers, pastors, and community members who can attest to his or her character. Family members are in the best position to put together a full picture of the child, which can help the prosecutor see more than the crime of which the child is accused.

Make your voice heard

Our policymakers are concerned about the issue of juvenile transfer in New Orleans. It is important that the City Council hear directly from families affected by the process. If your family member has been arrested for a transfer-eligible offense, and you want your councilmember to know about that experience, you should contact his or her office directly. If your family member’s case is still moving through the court system you should always consult his or her attorney before speaking to outside parties about the case.