Civil asset forfeiture: Unfair, undemocratic, and un-American

Since the advent of the War on Drugs, law enforcement agencies have used civil asset forfeiture laws to strip Americans of billions of dollars in cash, cars, real estate, and other assets. Under these state and federal laws, officers are legally empowered to seize property they believe is connected to criminal activity – even if the owner is never charged with a crime. In most states, the agencies are entitled to keep the property or, more typically, the proceeds from its sale.

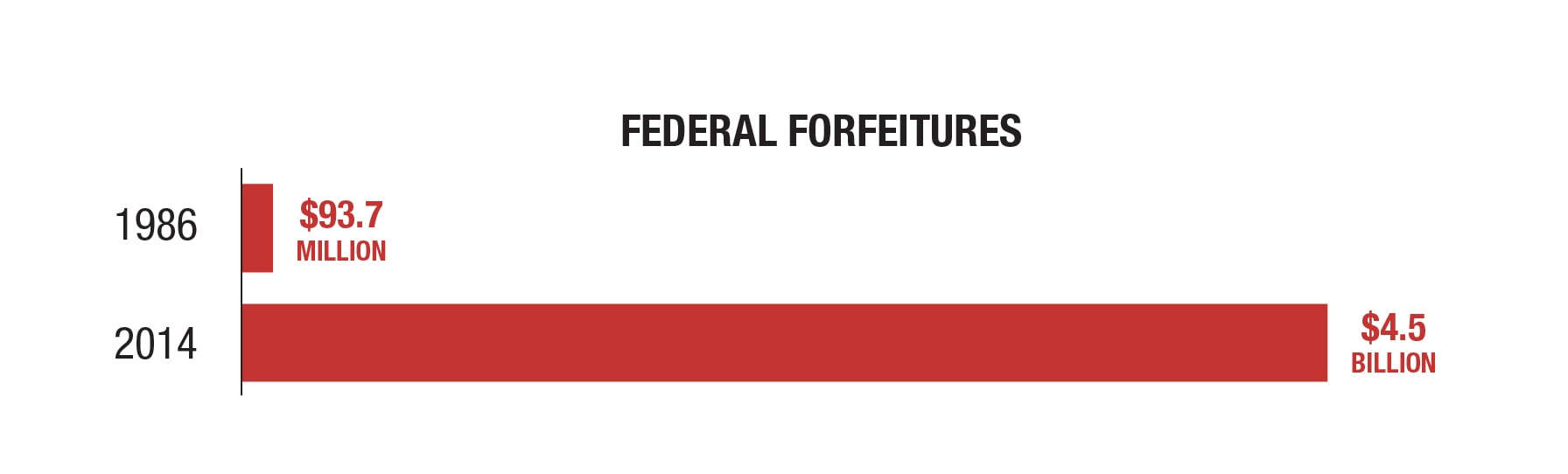

While federal forfeitures totaled $93.7 million in 1986, this revenue grew by more than 4,600% – to $4.5 billion a year – by 2014. Forfeitures handled by states have also poured millions, perhaps billions, of dollars into law enforcement agencies. As a result, there has been a massive transfer of wealth and assets from American citizens – and especially the most economically vulnerable – to police, who can largely use the funds however they see fit. Many states do not even require local agencies to track or report seized property. Though proponents of civil asset forfeiture claim that its revenue helps to fund more effective policing, evidence shows it has little impact on efforts to stop crime. Instead, it perverts the incentives of law enforcement, encouraging agencies to pursue strategies that maximize profit rather than ensure public safety.

In civil forfeiture cases, as many as 80% of people who have their assets seized are never charged with a crime. In most state and federal courts, the government is only required to show there is a “preponderance of evidence” (i.e., more likely than not) that the property abetted a criminal act. Proceedings are brought against the property, rather than the individual. These actions result in bizarre case names, such as State of Alabama v. One 2003 Toyota Corolla and United States of America v. $124,700 in U.S. Currency.

Without the need to issue a warrant or criminal charge, police are able to seize private property based on unsubstantiated claims. Using highway interdiction, for example, police can set up checkpoints, pull over motorists for minor violations, and seize their assets (usually cash) based on “indicators” of criminal activity. According to The Washington Post, these indicators can include signs as minor as “trash on the floor of a vehicle, abundant energy drinks or air fresheners hanging from rearview mirrors.” Law enforcement is also empowered to seize large assets, like a Massachusetts motel – frequently used as shelter for homeless families through Catholic Charities – that police insisted abetted drug activity. Homes have been seized from owners whose children or grandchildren were accused of committing drug crimes, even though the owners themselves were never implicated. In one money-laundering case in Florida, law enforcement seized approximately $49 million but did not bring a single indictment.

As a further complicating factor, in civil asset forfeiture cases the burden of proof in many states is placed on the property’s owner, who must prove that their property is unconnected to a crime. The costs associated with hiring a lawyer and paying court fees, especially in comparison to the value of the seized property, make forfeiture cases too costly and complicated for most people to defend. In an investigation into civil forfeiture in Philadelphia, for instance, half of all seizures of cash were in amounts less than $192, but taking off the four days required, on average, to attend court to resolve a case would cost a minimum wage-earning person $232 in lost income. Another investigative report found it took motorists an average of one year to resolve challenges to cash seizures. At the federal level, 88% of forfeitures go uncontested.

Modern civil asset forfeiture laws, created with the intent to incapacitate drug traffickers, were introduced by Congress as one component of the larger War on Drugs. The first drug-related civil asset forfeiture provisions appeared under the 1970 Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act and allowed law enforcement to seize drugs and all equipment used in their manufacture and transit. In the following years, Congress expanded the kinds of assets subject to forfeiture through civil action, rendering some assets’ connection to an alleged crime increasingly dubious. Civil forfeiture was also boosted under the 1984 Comprehensive Crime Control Act (CCCA). Unlike the 1970 law that had channeled revenue into the General Fund of the U.S. Treasury, the CCCA earmarked all forfeiture profits for law enforcement purposes. State civil forfeiture bills creating similar funding mechanisms followed. In effect, lawmakers created a financial incentive for policing agencies to prioritize anti-drug law enforcement.

Given civil forfeiture's lucrative ends, police departments have become heavily reliant on it. More than 60% of the 1,400 municipal and county law enforcement agencies surveyed in one study reported that forfeiture profits were a necessary part of their budget, leading the study’s author to conclude that departments were “addicted to the drug war.” In the nation’s capital, police even incorporated future seizures into their operating budget years in advance.

The drug war has unduly harmed racial minorities, and its civil forfeiture provisions are no different. Because of racial profiling, black and Hispanic motorists are disproportionately searched and put at risk of having their cash assets seized, even though black and white drivers are equally likely to be found with narcotics. A 1993 investigation by The Orlando Sentinel revealed that nine of every 10 motorists who were stopped and stripped of their cash by police in Volusia County, Florida, were either black or Hispanic, and three out of four were never charged with a crime. In Philadelphia, where nearly 300 houses are seized annually, African Americans make up 44% of the population but 63% of house seizures and 71% of cash forfeitures unaccompanied by a conviction. Forfeiture is also most likely to affect economically disadvantaged communities: One study found that areas with high income inequality were targeted for civil forfeiture operations, likely because these police departments have limited funding and are inclined to use forfeiture to secure needed revenue. The profile of suspects who have their as- sets seized, a researcher observed, “differ greatly from those of the drug lords, for whom asset forfeiture strategies were designed.”

Despite its initial aims, civil forfeiture has done little to aid the War on Drugs. Drugs are widely available at cheaper prices and higher potency than when the “war” began, and the most recent drug policy report from the Government Accountability Office, subtitled “Lack of Progress on Achieving National Strategy Goals,” points to its failures. Researchers have quantified civil forfeiture’s impact and found that, while there is small statistical support for the assertion that forfeiture leads to increased crime clearances, these effects are so small as to be immaterial. “The results,” they conclude, “undercut the argument that police retention of forfeiture funds is an essential element in the fight against crime.” In a March 2017 report, the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) Office of the Inspector General found that in 56 of 100 Drug Enforcement Administration forfeiture cases it examined, “there was no discernible connection between the seizure and the advancement of law enforcement efforts.”

What civil forfeiture has achieved, though, is a fundamental restructuring of law enforcement priorities. Rather than pursuing the most dangerous criminals, policing agencies and prosecutors target assets that promise the most lucrative returns.

One researcher, for example, noted that police commonly ran license plate numbers to determine the ownership status of vehicles. Did the suspect own the vehicle outright or was there a lien on the title? Cars with clear titles promised a larger profit when forfeited, making police more likely to pursue these cases.

Police also deploy strategies designed to generate cash revenue. The “reverse sting” is the preeminent example of policing’s shift from crime control to profit-making venture. In this type of operation, police act as drug dealers and make an exchange with a buyer, who is then arrested. In the end, cash and any assets associated with the transaction are seized, but no drugs are taken out of circulation. Patrick Murphy, the former police commissioner of New York City, described similar reasoning behind traffic checkpoints established outside the city. Police, he explained, have “a financial incentive to impose roadblocks on the southbound lanes of I-95, which carry the cash to make drug buys, rather than the northbound lanes, which carry the drugs. After all, seized cash will end up forfeited to the police department, while seized drugs can only be destroyed.”

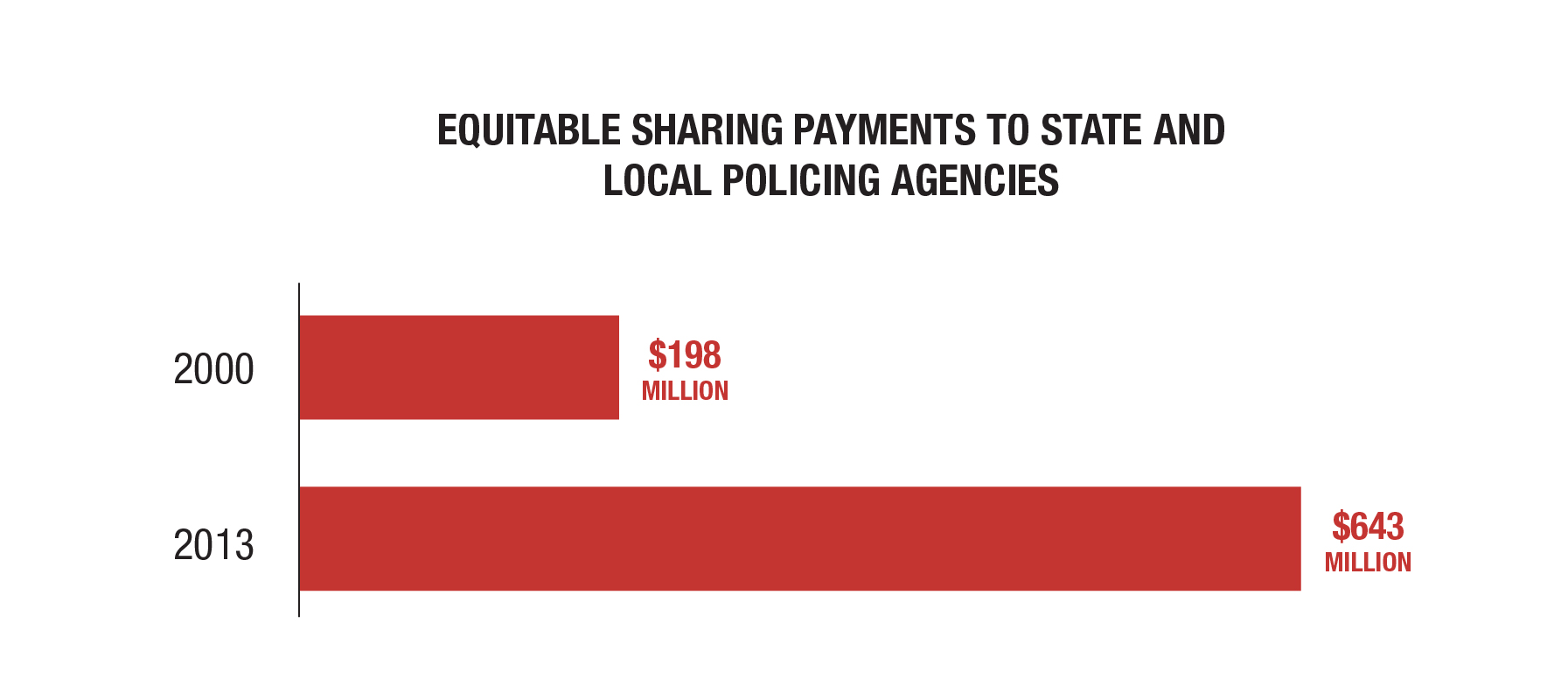

Police agencies also engage in an administrative procedure called “equitable sharing” that allows them to maximize forfeiture profits. Equitable sharing, introduced in the 1984 CCCA, allows federal “adoption” of seized assets, which the federal government rewards by giving local agencies up to 80% of the forfeiture revenue. Law enforcement agencies are thus authorized to circumvent more restrictive state forfeiture laws that might earmark revenue for social services or a general fund.

Studies have found that police agencies in states with restrictive forfeiture laws are far more likely to take advantage of equitable sharing, leaving social services shortchanged and police budgets bloated. In Missouri, for instance, state forfeiture proceeds were reserved “for school purposes only,” but, because the U.S. government’s equitable sharing program allowed policing agencies to sidestep these restrictions, only $12 million of the $41 million gained from forfeitures between 1993 and 2001 went to schools. Though Missouri instituted reforms to close this loophole, the vast majority of states continue to take advantage of the federal program: Equitable sharing payments to state and local policing agencies grew from $198 million to $643 million between 2000 and 2013. Equitable sharing undermines states’ attempts to regulate forfeiture, and its extensive use, according to criminologists, shows that police agencies “engage in forfeiture practices that maximize their potential for revenue generation.”

Since 2015, the equitable sharing program has been the subject of shifting policy within the DOJ. That year, Attorney General Eric Holder issued an order that limited its scope. Absent a federal seizure warrant or approval of the assistant attorney general overseeing the criminal division, the DOJ would no longer adopt and forfeit state-seized property unless it “directly relates to public safety concerns, including firearms, ammunition, explosives, and property associated with child pornography.” The DOJ suspended payments to law enforcement agencies in December 2015 but resumed them the following March. Then, more than a year later – and six months into the Trump administration – Attorney General Jeff Sessions re- versed Holder’s reforms altogether. Sessions in July 2017 announced a return to the “longstanding DOJ policy” of a more expansive program, with minimal additional procedural changes, including expediting federal notice of seizure to owners and requiring state or local law enforcement to provide more information about the probable cause for the seizure. In sum, while there has been a recognized need for reform within the DOJ, equitable sharing continues to provide an avenue for local and state law enforcement agencies to maximize their returns on forfeited property. Indeed, in its March 2017 report, the DOJ’s inspector general noted that more than $6 billion in forfeited funds had been shared with state and local law enforcement since fiscal year 2000.

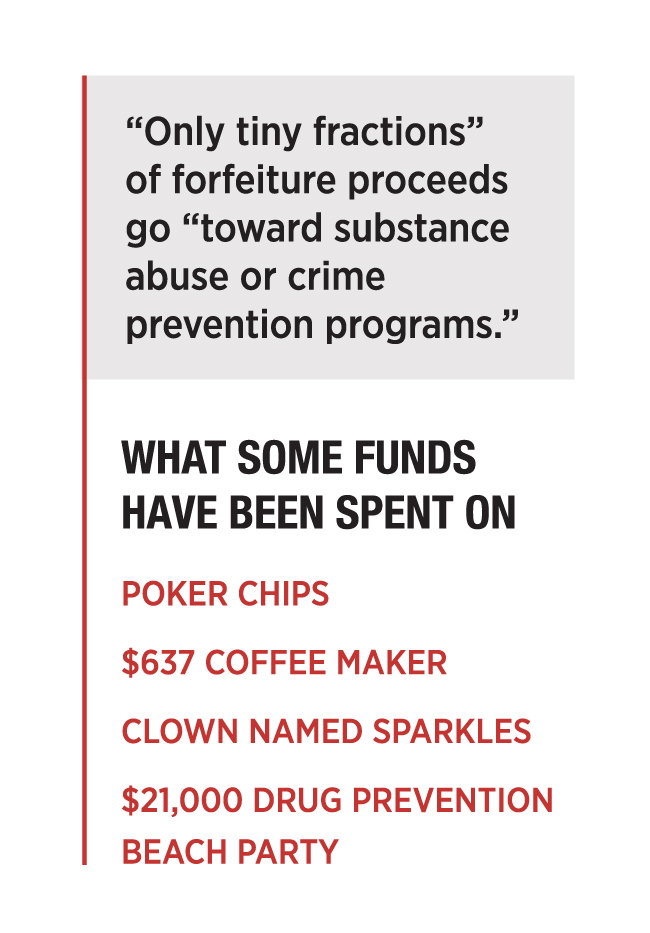

The ability to self-finance through civil forfeiture allows police departments to sidestep the usual appropriations channels, making them less accountable to the elected officials to whom they answer. They get to decide for themselves how forfeiture revenue is spent. While the income is regularly used to fund purchases like guns, cars, surveillance equipment, and training, these funds have also been spent on poker chips, a $637 coffee maker, a clown named Sparkles, and a $21,000 drug-prevention beach party. “Only tiny fractions” of forfeiture proceeds, an Institute for Justice report concluded, go “toward substance abuse or crime prevention programs.”

Much of this information is hidden from the public. There are no uniform reporting requirements for forfeiture data, and many of the state standards that do exist tend to be incomplete and vague. Without examining records in each case, it is often impossible to tell whether forfeiture was accompanied by a conviction, what kind of property was seized, or how proceeds were spent.

What is clear about civil forfeiture, though, is that it encourages policing for profit rather than the pursuit of justice. It does so by targeting and stripping the property and due process protections of vulnerable citizens, many of whom may be innocent of any wrongdoing and without the financial means to defend against the forfeiture. The system is badly in need of reform.

CONVICTION BEFORE FORFEITURE

Property should never be forfeited to the government without first obtaining a conviction of the underlying crime that is subjecting the property to forfeiture.

BURDEN OF PROOF

The government should bear the burden of proof, by clear and convincing evidence (not the lower civil standard of preponderance of the evidence), that an owner either knew that his property was being used for an illicit purpose or was otherwise willfully blind to the use of his property in criminal activity.

PROCEEDS

To remove the profit incentive of civil forfeiture, proceeds from forfeited property should be placed in neutral accounts, such as a state’s general fund – not in a local or state budget designated for a specific law enforcement agency.

EQUITABLE SHARING

Reforms should prohibit state and local law enforcement from sharing proceeds from forfeitures litigated in federal court, un- der the federal government’s equitable sharing program, as a way of by- passing state reforms.

PUBLIC REPORTING REQUIREMENT

Reform should require law enforcement agencies to account for what they seize and how they spend the proceeds.