The Biggest Lie in the White Supremacist Propaganda Playbook: Unraveling the Truth About ‘Black-on-White Crime'

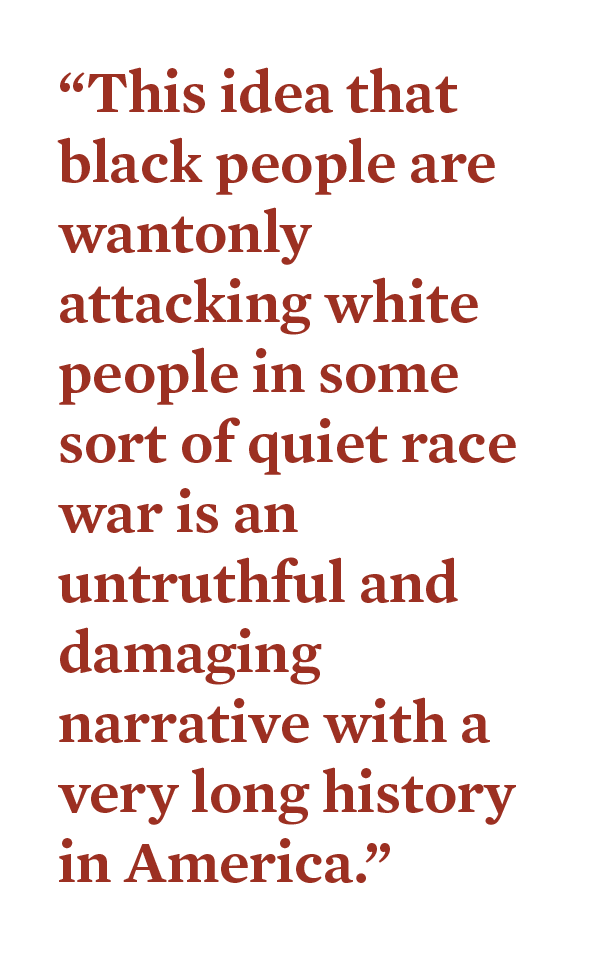

The idea that black people are wantonly attacking white people in some sort of quiet race war is an untruthful and damaging narrative with a very long history in America.

On a Wednesday night in June 2015, a 21-year-old white man walked into a black church in Charleston, South Carolina, and gunned down nine black parishioners taking part in a weekly Bible study group. Dylann Storm Roof sat quietly with the group for about an hour before taking out his Glock pistol and firing 70 rounds, stopping five times to reload. Court testimony revealed that during the shooting Roof said, “Y’all are raping our white women. Y’all are taking over the world.”

How this horrific violence came to take place traces back to a particularly destructive idea, one as old as the United States itself and rooted in the country’s white supremacy: that black men are a physical threat to white people. The narrative that black men are inherently violent and prone to rape white women, as Roof said during his rampage, has been prevalent for centuries. This idea has served as the primary justification for the need to oppress black people to protect the common — meaning white — good.

Roof saw himself as a victim standing up for oppressed whites, not as an aggressor. He had a racist “awakening” spurred by online research he did about the 2012 murder of the black high-school student Trayvon Martin. As he wrote in his manifesto, the Martin killing “prompted me to type in the words ‘black on white crime’ into Google, and I have never been the same since that day.”

Roof’s internet search quickly led him to the website of the white supremacist Council of Conservative Citizens, a group that claims to document an ignored war against whites being waged by violent black people. Google led Roof down a rabbit hole of hate, leaping from one hate site to the next, many filled with “evidence” that black people are pillaging, raping and murdering white people.

“There were pages and pages of these brutal black on White murders,” Roof wrote in his manifesto. “I was in disbelief. At this moment I realized that something was very wrong. How could the news be blowing up the Trayvon Martin case while hundreds of these black on White murders got ignored.”

It’s not surprising that a fragile-minded young man who swallowed hate material whole came to see this so-called problem of black-on-white crime as something he had to personally confront. But the resonance of these ideas goes much deeper, infecting the thinking of many prominent people, including public policymakers to this day.

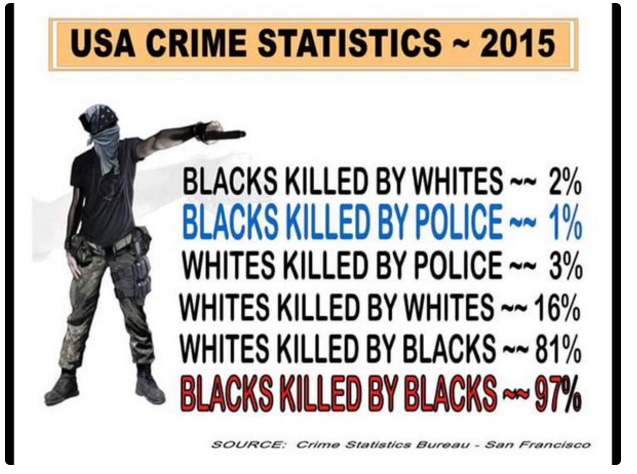

Take then-Presidential Candidate Donald Trump, who in November 2015 tweeted an image that originated from a neo-Nazi account that made exactly the same point as the hate sites Roof was reading. Filled with bogus crime statistics, the graphic Trump tweeted supposedly showed that black people are uniquely violent. The Washington Post found that the data in Trump’s tweet to be false. One of the most exaggerated statistics was about the number of white people killed by other white people. Trump’s tweet claimed the number was 16 percent, while the FBI’s data shows it is 82 percent. The tweet also asserted that 81 percent of whites are killed by black people; the FBI number is 15 percent. As the Post concluded, “Trump cast blacks as the primary killers of whites, but the exact opposite is true. By overwhelming percentages, whites tend to kill other whites. Similarly, blacks tend to kill other blacks. These trends have been observed for decades.”

It’s not just Trump. The far-right ecosystem repeats versions of these ideas ad nauseum. Relying on “statistics” found in a white supremacist tract, the paleoconservative one-time presidential candidate Pat Buchanan wrote in 2007: “The real repository of racism in America — manifest in violent interracial assault, rape and murder — is to be found not in the white community, but the African-American community.” Until very recently, Breitbart news used a “black crime” story tag.

Misrepresented crime statistics are a main propaganda point of America’s hate movement, and a pillar of white supremacist thinking in the United States. Stormfront, the oldest hate site on the internet, has thousands of pages devoted to the “issue” of black-on-white crime.

The idea that black people are wantonly attacking white people in some sort of quiet race war is an untruthful and damaging narrative with a very long history in America. White Americans’ unsubstantiated views about the potential of violence from black people was the number one excuse they used to justify slavery, lynching, Jim Crow and various forms of mass incarceration. Never was Klan violence or the lynching of black people by white people ascribed to an inherent white trait. Without the ability to claim oppression of black people as a form of self-defense, racial segregation and white supremacy would be seen for what they are: rank oppression of other people for financial or other benefit.

The maze of online white supremacist propaganda that Roof entered into is largely no more. Google cleaned up its search results after the Southern Poverty Law Center publicly exposed the problem in a January 2017 video. When black on white crime is typed into a Google search now, the results return legitimate sources of information, such as the FBI’s crime statistics, mainstream news and academic research.

But the idea of out-of-control black violence continues to motivate white supremacist propagandists and remains a main recruiting tool for the hate movement and its wish for a genetically pure white ethnostate. Because this narrative of black criminality is so central to American history — the foundation upon which discrimination has long been justified — it persists as white supremacy’s enduring siren song.

This report examines the origins and evolution of this propaganda from the mid-1800s to the current day.

Emancipation brought freedom to four million enslaved men and women, dismantling the codified racial hierarchy that much of white society believed to be natural. Most Southerners saw chattel slavery as rational, often drawing on the Old Testament to justify the institution. With its abolishment in 1865, white Americans had to adapt their ideas to the new legal regime and created new means of reinforcing the racial hierarchy where they sat at the top.

An early attempt to use “science” to preserve white supremacy

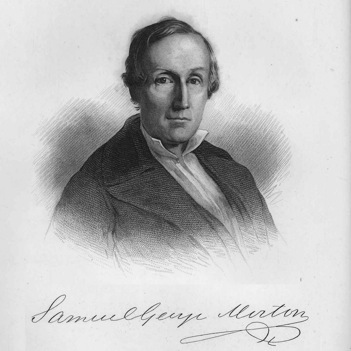

Attempting to address what came to be known as the “Negro Problem,” American scientists and other intellectuals created a new body of knowledge that they could use to justify white supremacy by scientifically “proving” black inferiority. Men like Samuel George Morton (1799 -1851), who is considered the originator of scientific racism, relied on anecdotal observations and physical measurements.

Morton built on a racial classification system first created by the Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus, which placed people in one of four groups:

- Americanus,

- Asiaticus,

- Africanus and

- Europeaeus.

In Linnaeus’ original work, Americanus were “obstinate, merry, free” and “regulated by customs,” while Africanus were “crafty, indolent, negligent” and “governed by caprice.”[1] Rather than simply ascribing characteristics to each race, Morton added a physiological layer to this racial taxonomy by measuring cranial capacity — studies he conducted using his personal collection of skulls, which was reputedly the world’s largest.[2]

Using buckshot and peppercorns to measure the volume of the skulls in his possession, Morton argued that Caucasians had the largest skulls and were, therefore, the most intelligent race.[3] Other thinkers ran with Morton’s ideas, especially after Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection gained widespread attention with its publication in 1859. Alabama physician Josiah Nott (1804 -1873), for instance, drew on patient observations and religious theory to argue that blacks and whites were, in fact, different species.[4]

From pseudo-science to lying with statistics

Craniometry was eventually replaced by a different kind of “proof” of black inferiority: crime statistics. Whereas the idea of racial difference was once perpetuated by pseudo-biological evidence, by the late-1800s new forms of statistical data — including datasets with a nationwide scope and new sampling techniques – became widely available. This new statistically based brand of social science seemed to provide a way to objectively measure how well black people had adjusted to life outside of slavery. The numbers showing that African Americans committed a disproportionate number of crimes appeared to affirm what many social scientists already believed to be true.

In his book The Condemnation of Blackness, historian Khalil Gibran Muhammad argues that this “racial data revolution” created a permanent linkage between blackness and criminality.[5] The myth that black people possessed a unique proclivity for violence became the most enduring way of communicating black inferiority and justifying continued discrimination.

The influential German-born statistician Frederick L. Hoffman, who would go on to serve as president of the American Statistical Association in 1911, played a crucial role in embedding the narrative of black criminality when he published the first book-length study of racial crime statistics. Hoffman trained in the American South and thoroughly absorbed the deeply racist culture that surrounded him. His interest in statistics developed as he read literature on “black disappearance” — the idea that the black race, through their own self-destructive behavior, would eventually vanish.

The release of the 1890 census afforded him the opportunity to test his theory that black people’s violent proclivities were contributing to high rates of black mortality. The census data he used in Race Traits and the Tendencies of the American Negro came 25 years after the end of slavery — enough time, Hoffman believed, that the conditions under which black people lived reflected only on black people themselves.[6]

Of course, black people at the turn of the century did not live under the same conditions as people who were white. After the Civil War, southern states were able to perpetuate the racial hierarchy and coerced labor that existed under slavery by making them central features of their judicial systems. As Douglas Blackmon documents in Slavery by Another Name, statutes criminalizing minor and subjective crimes allowed law enforcement to easily arrest black men, who were then leased to farmers and private industry as laborers to the financial benefit of the state.

For example, among the county convicts working in the Pratt Mines of Birmingham, Alabama in 1890:

- 24 men were incarcerated for using “obscene language,”

- Another 24 for “false pretense” — a statute used to punish black men who changed employers before the end of the farming season, and

- Seven for vagrancy, another ill-defined charge that left any unemployed black person vulnerable to arrest.[7]

In Alabama, the convict-leasing system remained on the books until 1928.

This context mattered little to Hoffman, who took crime statistics at face value, insisting they showed “without exception that the criminality of the negro exceeds that of other races of any numerical importance in this country.”[8] Environmental factors — including access to the most low-paying and dangerous jobs, segregation, exclusion from unions, discriminatory policing and other social and economic factors that might influence crime rates — were brushed aside. “It is not at all ‘the conditions of life,’” he wrote.[9]

Additionally, the fact that Irish and Italian immigrants also had disproportionately high crime rates received little notice. Hoffman quoted an academic who praised these immigrants for their ability to “melt like sugar in a cup of tea” when they came to the United States, while criticizing black people for remaining “distinctly African in their physical and mental characteristics.”[10] Like the other social scientists of his day, he wrote off higher crime rates among immigrant groups as a passing consequence of adjusting to the industrial city. In other words, it was temporary and environmental — an interpretation not afforded to African Americans.

The power of Hoffman’s interpretation lay in the fact that he argued with “data and reason, rather than passion and emotion,” giving a scientific veneer to racist ideas. Relying on dry and seemingly objective government reports, rather than the usual racist tropes, helped obscure the fact that his narrative was crafted to discredit claims of black equality. Hoffman’s “innovative and enduring significance,” Muhammad argued, “was not only in presenting the data for the first time, but also in setting the terms and shaping the frame of analysis.”[11]

By the turn of the century, the “Negro Problem” was a crime problem.

The real threat at the time: White on black crime

If anything, white people represented a far larger threat to black people than the reverse, and whites frequently employed the myth of black criminality to justify their own violence. The Klan represented an especial threat, and in their campaign of terror against newly freed African Americans they beat, whipped, kidnapped, and even killed men and women they believed had transgressed racial boundaries.

Often, it was the supposed sexual threat that black men posed to white women that elicited a violent response. Whites, especially in the South, cited rape and an alleged need to protect white women as a chief justification for the thousands of lynchings perpetrated against African Americans between Reconstruction and the Second World War.

Alleged sexual violence also sparked outbreaks of mass violence against black communities, including the 1908 Springfield, Illinois race riot and the 1921 Tulsa, Oklahoma race riot. Even the most well-to-do whites rationalized their own violence as necessary in order to defend their own racial purity and protect themselves against black barbarism.

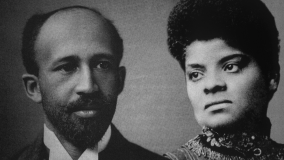

At the turn of the century, a cohort of black academics and activist journalists pushed back against the accusations that black people were uniquely criminal and their culture hopelessly dysfunctional. Most prominent among them were the sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois and investigative journalist Ida B. Wells.

In both his works The Philadelphia Negro (1899) and The Health and Physique of the Negro American (1906), Du Bois recontextualized statistical data to show that social and economic conditions were responsible for higher rates of black crime, disease and morbidity.

For her part, Wells disproved the widely accepted belief that lynching occurred in response to sexual violence committed by black men. Instead, she showed, lynching was a strategy for whites to maintain social control of black people through fear. She also cast white men as the perpetrators of sexual violence, describing the very real threat they posed to black women who had essentially no access to social or legal recourse.[12] The public failed to take the intellectual work of black men and women seriously, and it would be decades before their research reached the mainstream.

White supremacy is stubbornly resistant and adaptable. Indisputable racial progress was made during the mid-twentieth century, yet racists found new strategies to justify their ideology, defend racist policies and blame racial inequality on black pathology.

During the most active years of the Civil Rights Movement — as white supremacists watched their efforts to maintain segregation fail with the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and Voting Rights Acts in 1965 — they found a new way to demonstrate that black people were, in fact, inferior: the language of genetics.

“Advances in genetics, particularly the discovery of the double helix [structure of DNA] in 1953, confirmed the complexity of human heredity and continued to undercut the simplistic theories of eugenicists and other racial scientists who advanced the idea of a fixed racial taxonomy,” Michael Yudell, a scholar of bioethics and public health, explained in 2011. Yet, he continued, it also introduced language and methodology that could be “exploited and manipulated” by racists.[13]

Genetics provided white supremacists with a potent tool to argue that racial differences were scientifically based, inherited and thus immutable. Factors as far ranging as intelligence, health, impulsivity and criminality, racist academics argued, were based on genetic markers that varied by race.

The Pioneer Fund’s destructive enterprise

Academic racism in this vein was largely sustained by a single institution: The Pioneer Fund. According to William H. Tucker — whose 2002 book The Funding of Scientific Racism remains the definitive history of the organization — Pioneer bankrolled “almost every social scientist who has concluded that Blacks are genetically less intelligent than Whites.”[14]

The Fund’s overarching goal was to finance research that proved black genetic inferiority, which could then be cited as evidence that the low economic and social status of black Americans was “natural.” By extension, policy interventions — in the form of welfare or affirmative action, for example — could be written off as impotent and unnecessary.

These studies existed well outside of the scientific mainstream.

By 1972 leading genetic scholar Richard Lewontin concluded that race had “virtually no genetic…significance.”[15] Nevertheless, scientists funded by Pioneer — nearly all of whom were in fields other than the biological sciences — used the language of genetics to help maintain a biological argument for white supremacy, repackaging old white nationalist ideas in order to lend them a respectable and scholarly edge.

Founded in 1937 by Wickliffe Draper, a Massachusetts textile magnate who used his multimillion-dollar fortune to endow the project, the Pioneer Fund aimed to ensure “race betterment” through “study and research into the problems of heredity and genetics.”[16] It came into being when eugenic-thought was still prominent in American culture (the 1930s saw more legal sterilizations committed for eugenic purposes than any other decade), and when many Americans connected societal problems stemming from the Great Depression to genetic factors and cultural “disease.”[17]

The politics of the Pioneer Fund

Draper’s fervent belief in eugenics was matched by those of the Fund’s first president, Harry Laughlin, a legal scholar whose work inspired Nazi sterilization programs.[18]

Though Harry F. Weyher, Jr., a New York attorney who became the Pioneer Fund’s president in 1958, claimed the fund’s “sole activity” was to conduct disinterested scholarly research, it was a political project from the outset.[19]

After the Brown v. Board of Education decision outlawed school segregation, Draper began quietly funding efforts to fight subsequent civil rights legislation. By 1964, he anonymously donated nearly $215,000 (more than $1.7 million in 2018 dollars) to the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, a state-run agency created to oppose federal civil rights legislation, counter the work of anti-racist activists and preserve segregation.[20]

From the Sovereignty Commission, Draper’s donations were moved into the coffers of the Coordinating Committee for Fundamental American Freedoms, a nationwide initiative aimed at countering federal civil rights initiatives, which it called “$100 Billion Blackjack” in one newspaper ad.[21] Media campaigns were needed, Pioneer Fund associate John Satterfield explained, to demonstrate that African Americans’ position in society was due to genetic inferiority and not “environmental factors, particularly to mistreatment and ‘discrimination.’”[22] By the late 1970s, the Pioneer Fund was financing symposiums aimed at dismantling busing programs designed to desegregate schools.[23]

Funding racism through scholarship

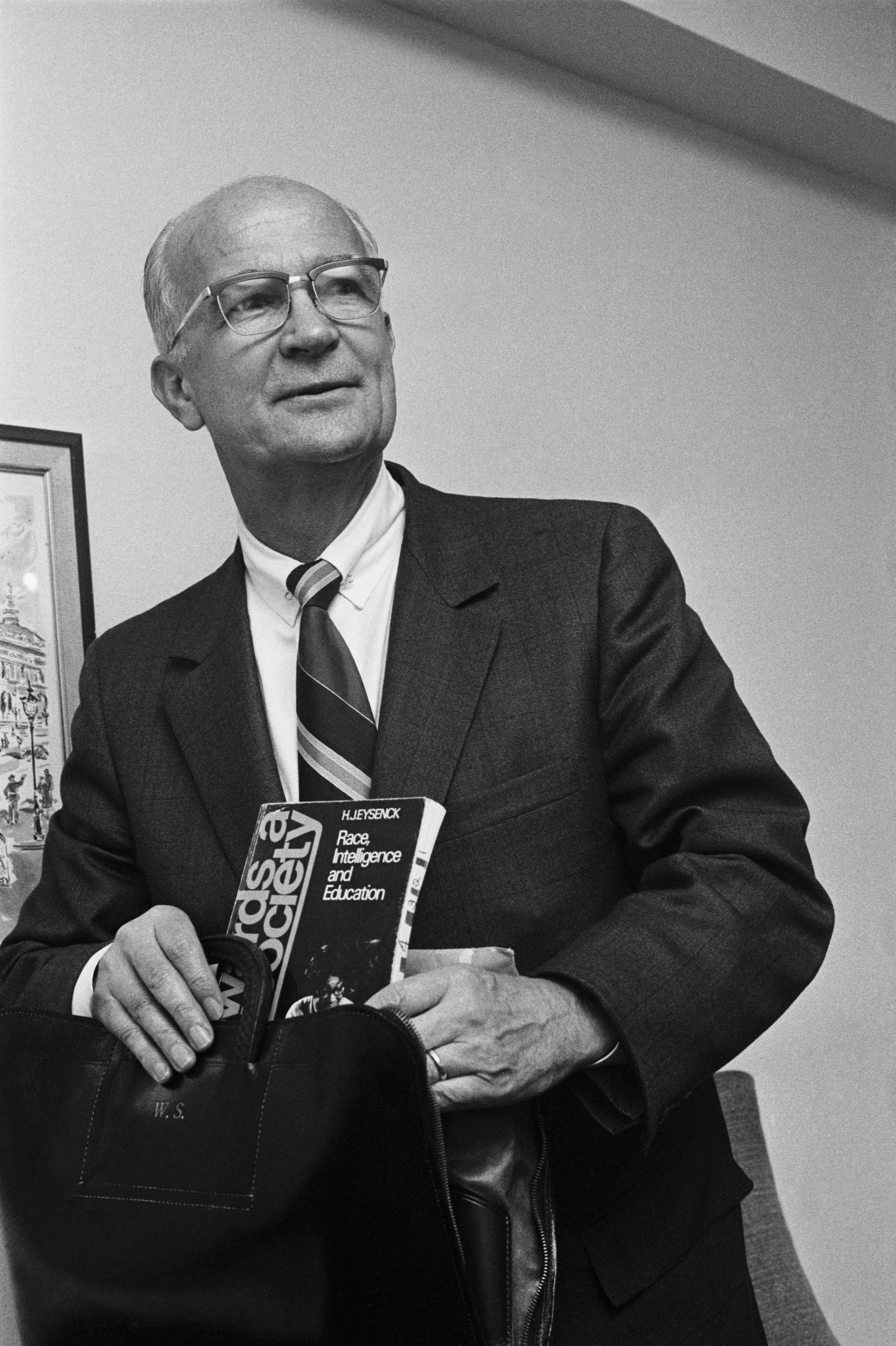

While the Pioneer Fund was privately operating in the political realm, its main project was to support the work of academics who focused on the intersection of race, genetics and public policy. The fund’s academic recipients worked in some of the nation’s premier research universities. Many of the main purveyors of racism in America were not men in hoods or mobs of angry Southerners blocking the entrances to schools, but well-educated professionals who were the epitome of middle-class respectability.

One of those men was Stanford professor William Shockley, who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1956 for his work on the transistor only to later become an ardent and outspoken eugenicist.

Shockley began his descent into scientific racism in 1965 with a lecture at that year’s Nobel conference on “Genetics and the Future of Man,” which argued that black Americans were suffering from “dysgenesis” — the theory that reproduction among those with substandard genetic makeup would eventually lead to the cognitive decline of an entire population.

Two years later he supplied a glowing review of a book called Race and Reality, which argued that allowing universal suffrage “to states or communities with high percentages of a retarded race is suicidal.”[24] Between 1968 and 1976 The Pioneer Fund granted Shockley the equivalent of nearly $1.5 million in 2018 dollars. With little to no training in biology or genetics Shockley never conducted original studies on intelligence, but still felt qualified to argue in 1980 that “The major cause of the US negro’s intellectual and social deficits are hereditary and racially genetic in origin and thus not remediable to a major degree by any practical improvements in environment.”[25]

Shockley spent most of his “research” money on a pseudo-academic, pro-eugenics media campaign, mailing lawmakers, writers, scientists and journalists bulging packets containing articles and his own racist dispatches.[26]

Shockley also made his own public policy proposals. His main target was welfare programs, which had grown in the 1960s thanks to a movement — led predominantly by black women — to organize the urban poor around the issues of public assistance. But their progress also brought increased scrutiny, especially toward black female welfare recipients.

These women, Shockley insisted, were having too many children and burdening society with an increasing number of genetically undesirable individuals. Welfare, he proposed in 1973, should be replaced by a “Voluntary Sterilization Bonus Plan” wherein women could elect to undergo sterilization and, for every point their IQ fell below the white mean of 100, they would receive $1,000.[27]

Other Pioneer recipients, like Johns Hopkins University sociology professor Robert Gordon, supported similar policies well into the 1990s. When a Columbia University student asked him whether black people should electively undergo sterilization, he replied: “If they care about the future of their race, they might be willing to go to some trouble to accomplish that. I think it's right to give them the proper information in order for them to do that.”[28]

Shockley’s biggest public relations campaign was not based on his own work, but that of his protégé Arthur Jensen, an education psychology professor at the University of California, Berkeley, whose infamous 1969 article in the Harvard Educational Review argued that black children were not genetically equipped to learn the same abstract concepts as white children.

The policy implications were clear, he insisted: social programs meant to improve the educational outlook for black students — specifically War on Poverty programs like Head Start — were useless and should be replaced by those with “eugenic foresight” like vocational training.

The article was roundly criticized by the emerging group of black activist-academics, including Angela Davis, but their critiques were drowned out by Shockley’s determined effort to spread Jensen’s findings to the media. Publications responded with dramatic headlines, like one in Newsweek that read “Born Dumb?”[29] Even the Regents at the University of California issued support for Jensen when they cited Davis’s criticisms of his article as one of the reasons she was fired from her post at UCLA.[30]

Two of the men who would eventually serve as presidents of the Pioneer Fund produced some of its most outlandish research. Psychologist J. Philippe Rushton, who managed the Fund between 2002 and 2012, argued in his work that black men had smaller brains, which was inversely correlated with the size of their genitals (his department at the University of Western Ontario reprimanded him in 1988 for conducting a survey in which he asked 150 men questions like “How large is your penis?” and “How far can you ejaculate?” at a shopping mall).[31]

Richard Lynn, a professor at the University of Ulster in Northern Ireland who took over the Pioneer Fund after Rushton’s death, wrote in 1974 that “If the evolutionary process is to bring its benefits, it has to be allowed to operate effectively. This means that incompetent societies have to be allowed to go to the wall… What is called for here is not genocide, the killing off of the populations of incompetent cultures. But we do need to think realistically in terms of ‘phasing out’ of such peoples.”[32]

The Pioneer Fund also bankrolled Mankind Quarterly, a pseudo-academic journal established by anthropologists in 1961 to promote studies exploring racial dissimilarities. Its founders included a proponent of South African apartheid, a Columbia professor who defended segregation in expert testimony for Brown v. Board of Education and a pro-Mussolini Italian eugenicist.[33] Between 1978 and 2015, the journal was published by the Pioneer-funded Institute for the Study of Man, founded by British anthropologist Richard Pearson, who in his own work warned that race mixing amounted to “racial suicide.”[34]

Mankind Quarterly took eugenicist thinking and flavored it with academic jargon to provide a veneer of legitimacy. This helped to enforce a self-referential “scientific” community among academic racists: they had a platform for their more outlandish work and could cite one another to create the appearance of scholarly consensus. Nevermind that the journal’s articles on the inherited mental capacities of different races were far outside the scientific mainstream.

The publication of political scientist Charles Murray and psychologist Richard J. Herrnstein’s bestselling book The Bell Curve in 1994 took the ideas about the genetics of race, intelligence, behavior and crime held by Pioneer Fund recipients and Mankind Quarterly contributors from the outskirts of public debate to the mainstream.

The nearly 1,000-page tome — built on the scholarship of race scientists supported by the Pioneer Fund — introduced the broader public to the ideas circulating in racist academic circles. And, because they presented their work as mainstream scientific consensus, the book lent white supremacists a hand in their quest to change the way Americans discussed the issue of race.

In The Bell Curve, Herrnstein, a Harvard professor who first broached the issue of race and IQ in a 1971 article in The Atlantic, teamed up with Murray, a fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, to examine racial and social stratification in America. The two social scientists argued that those who made up the American “underclass” were there not because of racial or socioeconomic disadvantage, but because of genetic deficiencies passed down through generations. The gap between the underclass and the “cognitive elite,” they insisted, was growing, and soon the problems posed by those who occupied the bottom of the intellectual ladder would worsen because “addiction, violence, unavailability of work, child abuse, and family disorganization will keep most members of the underclass from fending for themselves.”[35]

Who made up this underclass? The unemployed, welfare dependents, and, most controversially, African Americans who, due to a mix of genetic and environmental factors, had an average IQ 15 points lower than that of whites, the authors claimed.[36] Poor black people, they argued, fell into their low social and economic position because of differences in IQ.

All of this rested on scientifically questionable research. As Charles Lane pointed out in his critique of The Bell Curve for The New York Review of Books, “No fewer than seventeen researchers cited in the bibliography of The Bell Curve have contributed to Mankind Quarterly.”[37] In all, 13 scholars cited in the book received support from the Pioneer Fund, including Rushton, Lynn, Gordon and Jensen. It was thus, unsurprisingly, welcomed warmly by academic racists. Linda Gottfredson — a Pioneer Fund recipient cited by Herrnstein and Murray whose work on race and intelligence won praise from David Duke’s National Association for the Advancement of White People — penned a statement in support of the two social scientists in The Wall Street Journal. “We’d have funded Murray at the drop of a hat. But he never asked,” Pioneer Fund president Harry Weyher told GQ.[38]

Scholarly reviews of The Bell Curve were overwhelmingly negative. One critique, from three researchers at Carnegie Mellon University, plainly pointed to its central flaw: “Herrnstein and Murray give the impression that IQ is highly ‘heritable,’ but it is not.”[39] Instead, as researchers explained, IQ is not solely or even predominantly biologically determined, but shaped by a number of variables including education and environment. Critics noted that the book failed to mention the contextual factors that contributed to the growing ranks of the black underclass, including deindustrialization and the flight of jobs from American cities, the quality of education and the lack of wealth and resources black parents could pass on to their children.[40]

The Bell Curve’s Political Impact

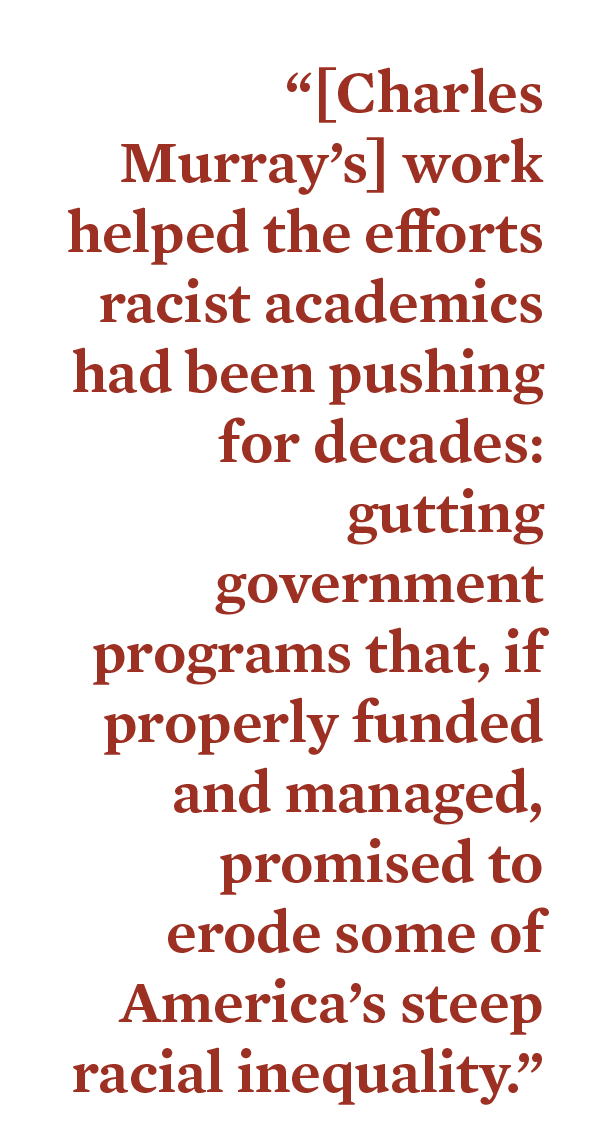

Despite its negative reception among scholars, The Bell Curve had enormous political implications. At the time of its publication, reforming the welfare system had become a top priority for lawmakers across the political spectrum — a movement to which Murray himself provided fuel. His earlier work, the 1984 book Losing Ground: American Social Policy, 1950-1980 argued that the welfare state bred dependency and crime and, in fact, harmed the poor by disincentivizing work. If you pay people not to work, he insisted, they will logically elect to stay unemployed and draw on as many benefits as are available. Though Murray’s assertion that welfare dependence was growing proved false (since 1975, the number of recipients had grown at roughly the same rate as the population), the book provided grounding for conservative politicians looking to justify reducing the social safety net.[41]The New York Times even called it the “budget-cutters’ Bible.”[42]

The public tended to blame women, and particularly mythical black “welfare queens” who committed fraud or had multiple out-of-wedlock births, for abusing the welfare system to gain generous government benefits. This belief was also reflected in the policy recommendations made in The Bell Curve. Echoing an idea frequently touted by eugenicist and Pioneer Fund recipient William Shockley, Herrnstein and Murray argued that welfare effectively “subsidize[d] births among poor women,” in effect increasing “dysgenic pressure” on American society. In other words, “unmarried mothers who are below average in intelligence” were having too many children, and thus lowering the nation’s intellectual potential, producing children with behavioral problems, and increasing the criminal population[43]

In testimony to the Senate Finance Committee in 1995, Murray drew on his research to urge lawmakers to make the “necessary brutal calculation” to reform welfare — something they would do the following year with a dramatic cut to the availability of cash benefits.[44]

Murray provided ideological underpinnings for welfare reform and helped elevate eugenicist thought into the world of mainstream political debate. His work helped the efforts racist academics had been pushing for decades: gutting government programs that, if properly funded and managed, promised to erode some of America’s steep racial inequality.

As The Bell Curve was making its way through the nation’s political circles, it was also making waves in the white nationalist movement. Members of the movement saw it as a legitimation of their long-held ideas. They took the reception of Murray and Herrnstein’s research as a cue that they could safely broach the topic of genetic differences in order to change public discussion of race. As Leonard Zeskind, an expert on white nationalism, recounts in his book Blood and Politics, the longtime Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke openly celebrated the ideas contained in The Bell Curve. The “scientific community is moving in our direction,” he told a room of white nationalists in 1994, “The ideas of The Bell Curve can’t be suppressed anymore.”[45]

Murray also received praise from American Renaissance (AR), a publication and website supported by the self-styled think tank the New Century Foundation. According to American Renaissance editor Jared Taylor, The Bell Curve said “something AR has been saying for years: The races do not have the same average intelligence.” “[T]he rules of dialogue in America may have finally changed,” he wrote hopefully. Maybe, people could now openly admit to their neighbors, “No, I don’t want blacks moving into the neighborhood because they are not like us.” The book, he concluded, had “done the country an enormous service.”[46]

The problematic publication American Renaissance

Taylor founded American Renaissance and the New Century Foundation in 1990, two years before the Yale-educated writer began to make a name for himself in conservative circles with the publication of his book Paved with Good Intentions: The Failure of Race Relations in Contemporary America. At the time, conservative consensus assumed that the problems plaguing many black communities in American stemmed from a dysfunctional black culture, but Taylor echoed the biological frame by placing the blame squarely on black people themselves. He laid out his argument in a debate about the “black-crime problem” in a 1994 issue of National Review: “the United States has neither a unique ‘culture of violence’ nor inadequate gun laws,” he concluded simply, “It has a high rate of violent crime because it has a large number of violent black criminals.”[47]

While the book earned him space in the foundational publication of conservative thought, Taylor turned his attention more fully toward American Renaissance, which promised to be a “literate, undeceived journal of race, immigration, and the decline of civility.” With the help of a large cadre of racist intellectuals, the publication presented white nationalist ideas in a disinterested, journalistic style, and no idea received more space on its pages than black crime.

American Renaissance’s inaugural issue warned white people not to be “silent accomplices” to their own “dispossession.” He told readers that white people should not be ashamed to discuss their group interests. “Others—sincere, thoughtful, concerned Americans—have been convinced that it is improper, even immoral, for white people to think of themselves as a group or to speak out as white people,” Taylor wrote, “We believe that in the pages of American Renaissance these people will find reasons to think that it is not only moral but necessary.” He included a note of caution: “If we continue to permit the erosion of the essential conditions of nationhood, and indeed, of any healthy sense of neighborhood and community, the frictions that torment us today will be as nothing compared to the chaos that will come. The squalor of Detroit, the violence of Washington (DC), and the savagery of New York City must not mark the way to the future.”[48]

The list of contributors at American Renaissance overlapped considerably with that of Mankind Quarterly, and both publications contained many of the same “race realist” arguments. Richard Lynn, for instance, wrote a 2002 cover story arguing that black people were “more psychopathic than whites,” rendering them unable to control their own impulses. As a result, African Americans engaged in reckless sexual behavior, had unstable relationships, committed more crimes and had lower credit scores.[49]

Taylor’s cohort of professional racists repeated these same fallacies at American Renaissance conferences, faux-academic affairs held biannually beginning in 1994 that have attracted a wide variety of characters from the racist far right. At a 1998 meeting, Glayde Whitney, a behavioral psychologist at Florida State University, gave a presentation in which he argued that black women developed larger buttocks — the “human equivalent of a camel’s hump” — to survive in harsh African climates. He also stated that black people possess an innate tribal tendency, and that the “many rapes of white women by blacks is a typical expression of dominance.”[50]

American Renaissance uses Hurricane Katrina to push its narrative

Hurricane Katrina, which decimated the majority-black city of New Orleans in 2005, seemed to confirm all that American Renaissance had purported to be true about African Americans, namely that they would resort to “barbaric behavior” if removed from the protective rails of white society.

In his longform essay “Africa in Our Midst,” Taylor described the city as a “jungle.” “[T]he most serious damage,” he wrote, “was done not by nature but by man.” The hurricane provided an excuse for the city’s black residents to “loot, rob, rape and kill” — alleged actions he described in graphic detail. The lesson? “Blacks and whites are different. When blacks are left entirely to their own devices, Western Civilization—any kind of civilization—disappears.”[51]

Taylor’s accounting of events turned out to be false. “It now appears that press reports on the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina exaggerated the mayhem in the New Orleans Convention Center and at the Superdome,” he conceded in a second piece. He nevertheless defended his original conclusions, insisting that the chaos he described easily could have taken place. News outlets reported gruesome accounts because they seemed “entirely plausible.” “In their bones, even writers for the New York Times believe crowds of blacks can easily descend into anarchy,” Taylor wrote.[52]

Taylor’s pieces on Katrina were emblematic of the way his outlet discussed the issue of black crime. But perhaps no other American Renaissance contributor and conference mainstay more fully explored the issue of race and criminality than Michael Levin, a philosophy professor at City University of New York since 1969. While his early work focused on the philosophy of mathematics, by the 1980s he was predominantly interested in writing philosophical critiques of feminism and affirmative action (he argued in an Australian publication that the most troubling aspect of the American educational system was “the staggering energy expended to bring American Negroes into the educational mainstream”).[53]

The question of race and intelligence came to dominate his work, leading to widely publicized showdowns between Levin and his university and, eventually, to CUNY offering students alternatives to Levin’s classes.[54]

Michael Levin, with Pioneer Fund backing, pushes his ideas on race

In 1997, with the financial support of the Pioneer Fund, Levin published Why Race Matters, a treatise against government efforts to remedy racial inequality. Levin argued that “race differences, far from being neutral, undermine almost everything that has been said about race for the past 60 years, and the many policies based on this conventional wisdom.” Whites, he insisted, “owe blacks no compensation in any form because the limitations of blacks are byproducts of genetic differences, not injuries done by whites.” Even vastly higher rates of black infant mortality, Levin wrote, could be explained as a biological phenomenon.[55]

A great percentage of the material appearing in Why Race Matters was recycled from other Pioneer Fund grantees, including Richard Lynn and J. Philippe Rushton. However, Levin’s condemnations of black character, morality and values were considerably more overt, and he linked these shortcomings to a propensity to commit crime. White people, he argued, were wasting energy on “white guilt” over social conditions that could not be remedied and should forgive themselves for harboring a “rational” fear of black violence.[56]

Through statistics and lists of crimes, Levin insisted that whites should be “alarmed not only by the frequency of black crime, but by the extremes of depravity and indifference to human life.” As a remedy, he proposed harsher systems of punishment — corporal punishment, the death penalty and chain gangs — as well as race-conscious policing and the use of technology that could identify potential criminals.[57]

The book sold poorly in its first printing, but Taylor swooped in to improve its sales, republishing it in 2005. Taylor, Jensen and Rushton supplied blurbs on the book’s back cover to give it the appearance of scholastic respectability and support.[58]

With its scientific jargon and lengthy footnotes, Levin’s book provided scholarly heft to the racist argument that black people were natural-born criminals. It was, however, an unwieldy volume for the average reader to wade through.

Spinning crime statistics

To reach a wider audience, Taylor produced The Color of Crime: Race, Crime and Violence in America, a brief 1999 report that relied on a sloppy interpretation of crime statistics linking race and IQ, and thus claiming that crime has a racial and biological basis. It purported to provide indisputable proof that not only did black people commit more crimes, but also that there was an epidemic of black-on-white violent crime that went unreported.

The findings of the report drew on an authoritative source: the “1994 Crime Victimization Survey” released by the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics. While Taylor’s reporting of the statistics was accurate — there were, in fact, higher rates of violent crime committed by black people, and crimes committed by blacks against whites than the reverse — his interpretation of the data was flawed.

By taking crime statistics at face value, Taylor made the same mistake Frederick Hoffman did in 1896: blaming higher rates of black crime on an innate black criminality, when in fact those disproportionate crime rates could be explained by poverty and related structural disadvantages. On average, African Americans were — and remain — far poorer and more likely to live in disadvantaged neighborhoods than whites. Concentrated poverty has a criminogenic effect: lack of access to jobs, increased idle time and poorer educational opportunities all increase one’s chances of engaging in criminal behavior, and the effect is the same for black and white people. One study, released three years before The Color of Crime, found that when sociologists controlled for structural disadvantages, there were no significant differences between crime rates in black and white communities.[59]

A 2014 Bureau of Justice Statistics study showed that persons from poor households experienced the highest rates of violent victimization, and that rates were consistent for both blacks and whites.[60] When sociologists asked “Is Poverty’s Detrimental Effect Race-Specific?” they found the answer was no: policies aimed at reducing poverty effectively reduced violent crime and the crime reduction rates were similar in both black and white neighborhoods, meaning it was poverty — rather than race — that contributed to the violent crime rate in the first place.[61]

Taylor’s claim that blacks consciously targeted whites and were, in fact, committing “hate crimes,” presupposed that all interracial crimes were acts of racial malice. While Taylor suggested interracial crime was a rampant problem, the vast majority of violent crimes are intraracial, meaning victims and perpetrators are far likelier to be of the same race. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics report from 2000, among white victims of violent crime, 73 percent were attacked by other whites. Among black victims, 80 percent were victimized at the hands of another black person.

The argument that black people who commit crimes are specifically seeking out white victims is simply not true. In an article in the American Journal of Sociology, for example, sociologist Robert M. O’Brien pointed out that population size and the impact of segregation help explain why overall rates of black-on-white crimes are higher than white-on-black crimes. Essentially, black people are far more likely to come into contact with white people in the course of their daily life than the other way around.[62]

Despite its many methodological errors, Taylor released updated versions of The Color of Crime in 2005 and 2016, which feature new sections on discriminatory policing. It continues to be a standard text within white nationalist circles.

Like many budding white supremacists, Dylann Roof immersed himself in black-on-white crime propaganda before unleashing his anger on innocent black people in a Charleston church in 2015. Roof’s heinous act was just one flashpoint in a long history of white supremacy, scientific racism and the demonization of black people as biologically criminal. Ideas that the Pioneer Fund lent scientific credence to and American Renaissance helped propagate were absorbed by racist organizations like the Council of Conservative Citizens (CCC), and the internet made their ideas accessible to anyone with access to the internet. Roof’s blatant racism was at once outmoded and entirely present: Its roots lie centuries in the past, but its main thrust has been carried through with the help of patrons and propagandists.

The CCC, which played a decisive role in Roof’s radicalization, originated in the Jim Crow South. It is the modern reincarnation of the White Citizens’ Council, an organization that formed in southern states following the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education expressly to oppose desegregation. Local Councils tended to be populated by business elites, bankers and the well-to-do. Historian Charles Payne described them as “pursuing the agenda of the Klan with the demeanor of the Rotary Club.”[63]

Though membership in the CCC declined in the decades following the passage of federal civil rights legislation, it was revived in 1985 by Gordon Baum, a workers’ compensation attorney who used the old Citizens’ Council mailing list to recruit members. Scandal erupted in 1998 when it was revealed that former Congressman Bob Barr (R-Ga.) and then-Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott (R-Miss.) had ties to the hate group. Barr had spoken at that the CCC’s convention that year, and Lott had addressed the group on five separate occasions.[64]

They were not alone: a 2004 Intelligence Report investigation revealed that, between 2000 and 2004, 38 U.S. elected officials who were then in office had attended CCC events.[65] After Roof’s actions brought renewed scrutiny to the CCC in 2015, The Guardian reported that the white supremacist organization was still making large contributions to top Republican officeholders like Texas Senator Ted Cruz, who promised to return the donation after the news outlet approached him with questions.[66]

The CCC and like groups rely on the web to spread dangerous ideas

Since its height in the late 1990s, the CCC has abandoned much of its respectable veneer and, at the same time, moved its presence predominantly into online spaces. Its website now exists to “educate” white Americans about the dangers of black criminality and, at the time Roof came across it, the CCC hosted what it called a “memorial wall” to white victims of black criminals whose deaths went “unnoticed by the national media.”

New Nation, the first website devoted entirely to the issue of black-on-white crime, is organized similarly. Headlines like “(White) North Fort Myers man hospitalized after group beating at party by pack of savage jungle blacks” dominate the page, alongside mugshots and depictions of African Americans as apes. Like Taylor in The Color of Crime, many of these kinds of websites explicitly refer to interracial crimes as “hate crimes,” but few would meet the FBI’s hate crime definition of an “offense against a person or property motivated in whole or in part by an offender’s bias against a race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, ethnicity, gender, or gender identity.”[67]

Included in the CCC list, for instance, is the 2014 death of Anita Walters of Vancouver, Washington, a white woman killed in a hit-and-run by Matthew Purifoy, a black man who had a long history of reckless driving.[68] There is no evidence to suggest the vehicular homicide was motivated by hate. Many of the crimes listed on CCC’s list are domestic disputes, home invasions and robberies. While these crimes are often brutal, there is no evidence to suggest offenders targeted their victims because of their race and the “hate crime” designation is merely used to perpetuate the myth that black people pose a particular threat to white Americans.

After Roof’s manifesto was made public, even the CCC’s president, Earl P. Holt III, conceded that he was unsurprised to see his organization cited. “The CofCC is one of perhaps three websites in the world that accurately and honestly report black-on-white violent crime, and in particular, the seemingly endless incidents involving black-on-white murder,” he said in a statement. He noted that they should not be held responsible for a “deranged individual” gaining “accurate information from our website.”[69]

The prosecutors in Roof’s case claimed that he “self-radicalized,” but this phrase fails to capture the online milieu in which Roof developed his views — where those who hold white supremacist beliefs are constantly trying to convert others.[70]

“The internet gives millions access to the truth that many didn’t even know existed,” David Duke observed in 2007. “Never in the history of man can powerful information travel so fast and so far. I believe that the Internet will begin a chain reaction of racial enlightenment that will shake the world by the speed of its intellectual conquest.”[71]

The internet has made it immeasurably easier for white nationalists to gather, publish articles, discuss ideas and reach out to those like Roof who might be amenable to their messages. Their methods might be new, but the arguments they make with the hopes of perpetuating and codifying racial oppression have thrived for centuries.

[1] Audrey Smedley and Brian D. Smedley,Race in North America: Origin and Evolution of a Worldview, 4 th ed. (Philadelphia: Westview Press, 2012), 218-219. Back to report.

[2] Ann Fabian, The Skull Collectors: Race, Science, and America’s Unburied Dead (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 1. Back to report.

[3] Ibid., 15-16. Back to report.

[4] Khalil Gibran Muhammad, The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010), 22-23. Back to report.

[5] Ibid., 33. Back to report.

[6] Ibid., 32-37. Back to report.

[7] Douglas Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Reenslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War Two (New York: Anchor Books, 2008), 99-100. Back to report.

[8] Frederick L. Hoffman, Race Traits and the Tendencies of the American Negro (New York: American Economic Association, 1896), 228. Back to report.

[9] Ibid., 224. Back to report.

[10] Ibid., 195. Back to report.

[11] Muhammad, 53, 51. Back to report.

[12]Ida B. Wells, “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases,” 1892. Back to report.

[13] Michael Yudell, “A Short History of the Race Concept,” in Race and the Genetic Revolution: Science, Myth, and Culture, eds. Sheldon Krimsky and Kathleen Sloan (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011), 20-21. Back to report.

[14] William H. Tucker, “To Win the War: Racial Research and the Pioneer Fund,” in White Logic, White Methods: Racism and Methodology, eds. Tukufu Zuberi and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2008), 285-286. Back to report.

[15] Quoted in Yudell, “A Short History of the Race Concept,” 23. Back to report.

[16] Tucker, The Funding of Scientific Racism: Wickliffe Draper and the Pioneer Fund (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2002), 6-7. Back to report.

[17] Susan Currell and Christina Cogdell, eds., Popular Eugenics: National Efficiency and American Mass Culture in the 1930s (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2006), 1-3. Back to report.

[18] Adam Miller, “The Pioneer Fund: Bankrolling the Professors of Hate,” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no, 6, (Winter 1994-1995): 58. Back to report.

[19] Tucker, “To Win the War,” 286. Back to report.

[20] Tucker, The Funding of Scientific Racism, 122-123. Back to report.

[21] Joseph Crespino, In Search of Another Country: Mississippi and the Conservative Counterrevolution (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007), 93. Back to report.

[22] Tucker, “To Win the War,” 290. Back to report.

[23] Dick Kaukas, “Fund Aids Race-Based Intelligence Studies, Busing Foes,” The Courier-Journal, October 16, 1977. Back to report.

[24] Tucker, The Funding of Scientific Racism, 140-142. Back to report.

[25] Ibid., 144-145; “Playboy Interview: William Shockley,” Playboy Magazine, April 1980, 69. Back to report.

[26] Tucker, The Funding of Scientific Racism, 147. Back to report.

[27] Ibid,, 145-146. Back to report.

[28] “The Racial Genetics of Intelligence: The Gadfly Interview with Dr. Robert Gordon,” The Gadfly, n.d. [1995?], http://psych.utoronto.ca/users/reingold/courses/intelligence/cache/eugenics2.html (accessed May 24, 2018). Back to report.

[29] Tucker, The Funding of Scientific Racism, 148-149. Back to report.

[30] Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America (New York: Nation Books, 2016), 412. Back to report.

[31] Extremist profile: Jean-Phillipe Rushton, Southern Poverty Law Center, https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/individual/jean-philippe-rushton , accessed May 16, 2018; Miller, “The Pioneer Fund,” 60. Back to report.

[32] Barry Mehler, “Academia at Forefront of Racist Ideals, White Supremacy,” The Intelligence Report. March 15, 1999. Back to report.

[33] Charles Lane, “The Tainted Sources of the Bell Curve,” The New York Review of Books, December 1, 1994. Back to report.

[34] Roger Pearson, Eugenics and Race (London: Clair Press, 1966), 26. Back to report.

[35] Richard J. Herrnstein and Charles Murray, The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (New York: Free Press, 1994), 523. Back to report.

[36] Ibid., 308. Back to report.

[37] Lane, “Tainted Sources.” Back to report.

[38] Miller, “The Pioneer Fund,” 61; “Mainstream Science on Intelligence,” The Wall Street Journal, December 13, 1994. Back to report.

[39] Quoted by Nicholas Lemann, “The Bell Curve Flattened,” Slate, January 18, 1997. Back to report.

[40] See Nina J. Easton, “Book That Links Low IQ to Race, Poverty Fuels Debate,” L.A. Times, October 30, 1994. For a robust analysis of the black “underclass,” see William Julius Wilson, When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor (New York: Vintage Books, 1996). Back to report.

[41] Edward Mattison, “Stop Making Sense: Charles Murray and the Reagan Perspective on Social Welfare Policy and the Poor,” Yale Law & Policy Review, Vol. 4, no 4 (1985), 94; For a comprehensive critique, see Sara McLanahan et al., “Are We Losing Ground?” Focus 8, no. 3 (1985), http://www.irp.wisc.edu/publications/focus/pdfs/foc83a.pdf (accessed May 25, 2018). Back to report.

[42] “Losing More Ground,” The New York Times, February 3, 1985. Back to report.

[43] Herrnstein and Murray, The Bell Curve, 548, 519. Back to report.

[44]Judith Havemann, “Bell Curve Author Addresses Welfare,” The Washington Post, April 28, 1995. Back to report.

[45] Leonard Zeskind, Blood and Politics: The History of the White Nationalist Movement from the Margins to the Mainstream (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009), 395. Back to report.

[46] “O Tempora, O Mores! Breakthrough on Race?” American Renaissance, December 1994. Back to report.

[47] Jared Taylor, response to “Blacks, Jews, Liberals, and Crime,” National Review, May 16, 1994, 45. Back to report.

[48] “Who Speaks For Us?” American Renaissance, November 1990. Back to report.

[49] Richard Lynn, “Race and the Psychopathic Personality,” American Renaissance, July 2002. Back to report.

[50] “The Tenures Professor Who Teaches Black Biological Inferiority at Florida State University,” The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, no. 24 (1999), 84-85. Back to report.

[51] Taylor, “Africa in Our Midst,” American Renaissance, vol. 16, no. 10, October 2005. Back to report.

[52] Taylor, “Postscript on Katrina,” December 2005. Back to report.

[53] Joseph Berger, “Professors’ Theories on Race Stir Turmoil at City College,” April 20, 1990; quoted in Richard Brookhiser, “Fear and Loathing at City College,” National Review, June 11, 1990, 21. Back to report.

[54] Extremist profile: Michael Levin, Southern Poverty Law Center, https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/individual/michael-levin (accessed May 26, 2018). Back to report.

[55] Michael Levin, Why Race Matters: Race Differences and What They Mean (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger Publishers, 1997; reprint, New Century Foundation, 2005), 2, 10, 13. Back to report.

[56] Ibid., 10. Back to report.

[57] Ibid., 291, 359. Back to report.

[58] Though his book can still be purchased through the American Renaissance website, Levin, along with several other Jewish participants, severed ties with the organization in 2006 after an eruption of anti-Semitism at that year’s conference. Taylor has tried to suppress the “Jewish question” on the pages of American Renaissance and within the halls of its conferences, but the issue is too prevalent in white nationalist circles to be successfully cordoned off. Back to report.

[59] Lauren J. Krivo and Ruth D. Peterson, “Extremely Disadvantaged Neighborhoods and Urban Crime,” Social Forces, Vol. 74, no. 2 (December 1996): 619-650. Back to report.

[60] U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Household Poverty and Nonfatal Violent Victimization, 2008-2012,” November 2014, 4. Back to report.

[61] Lance Hannon and Robert DeFina, “Violent Crime in African American and White Neighborhoods: Is Poverty’s Detrimental Effect Race Specific?” Journal of Poverty, Vol. 9 (2005): 49-67. Back to report.

[62] Robert M. O’Brien, “The Interracial Nature of Violent Crimes: A Reexamination,” American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 93, no. 4 (Jan., 1987): 817-835. On black rapists seeking out white victims, see Larry Koch, “Interracial Rape: Examining the Increasing Frequency Argument,” The American Sociologist, Vol. 26, no. 1 (1995): 76-86. Back to report.

[63] Charles Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 34-35. Back to report.

[64] Extremist profile: Council of Conservative Citizens, Southern Poverty Law Center, https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/group/council-conservative-citizens (accessed May 26, 2018). Back to report.

[65] “Dozens of Politicians Attend Council of Conservative Citizens Events,” Intelligence Report, October 14, 2004. Back to report.

[66] Jon Swaine, “Leader of Group Cited in ‘Dylann Roof Manifesto’ Donated to Top Republicans,” The Guardian, June 22, 2015. Back to report.

[67] “Hate Crimes,” https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/civil-rights/hate-crimes (accessed May 26, 2018). Back to report.

[68] “DUI Driver Who Hit and Killed Woman in Vancouver Sentenced to Prison,” KPTV.com, March 30, 2015. Back to report.

[69] Lindsey Bever, “‘Supremacist’ Earl Holt III and His Donations to Republicans,” The Washington Post, June 23, 2015. Back to report.

[70]Mark Berman, “Prosecutors Say Dylann Roof ‘Self-Radicalized’ Online, Wrote Another Manifesto in Jail,” August 22, 2016. Back to report.

[71] Quoted in Jessie Daniels, Cyber Racism: White Supremacy Online and the New Attack on Civil Rights (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2009), 3. Back to report.