The Year in Hate & Extremism Report 2021

In this section

• Meeting the challenge of the hard right

• Where extreme meets mainstream

• The right’s embrace of violence

• Proud Boys membership spikes

• White Nationalist and Neo-Nazi groups continue to adapt

• The Antigovernment Movement takes a hit, but gets back up bruised and battered

• Mainstream hate reorients without the White House in its pocket

• History tells us that the threat is real

By Cassie Miller and Rachel Carroll Rivas

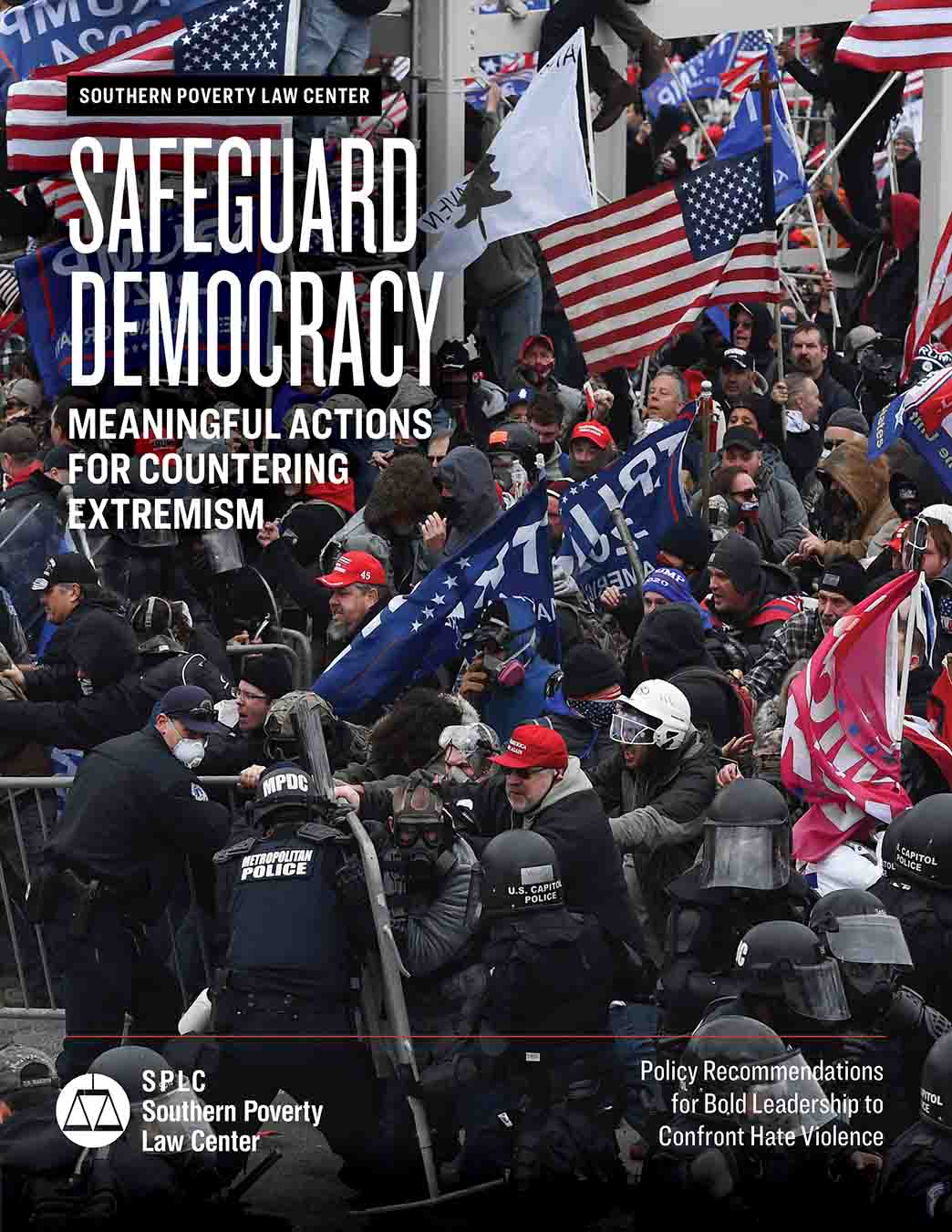

The storming of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 exposed an alarming reality: that extremist leaders can mobilize large groups of Americans to use force and intimidation to impose their political will. The reactionary and racist beliefs that propelled a mob into the Capitol that day have not dissipated. Instead, they’ve coalesced into a political movement that is now one of the most powerful forces shaping politics in the United States.

In the year since the insurrection, this hard-right movement — made up of hate and extremist groups, Trump loyalists, right-wing think tanks, media organizations and committed activists with institutional power — has worked feverishly to undermine democracy, with real-world consequences for the people and groups they target. Within the GOP, a radical faction is attempting to rout the few remaining moderates unless there is a robust counter-effort from democracy supporters.

Many Republicans and a monied network of ally groups have exploited the “Big Lie” of a stolen election in 2020 to enact a historic number of voter-suppression bills that disproportionately disenfranchise voters of color and people in poverty. They have rallied their base against inclusive and anti-racist education and introduced a slew of bills that would allow discrimination against transgender people and gut the teaching of Black history. Attempts to ban books are on the rise, targeting materials that discuss race, sexuality and gender. Some Republican members of Congress have worked together with open white nationalists and promoted the racist “great replacement” conspiracy theory that has inspired numerous deadly terror attacks. They have scapegoated the Asian American community for COVID-19, harassed public health officials and election administrators, celebrated a vigilante who killed two protesters at a Black Lives Matter demonstration, and defended insurrectionists.

These actions discourage and even prevent people from marginalized groups from fully participating in the political sphere and normalize the use of intimidation, force and violence against people the right deems threatening to their agenda. In many instances — especially the assault on education — they are designed to chill any discussion of racism and other forms of discrimination.

Extremist groups have also found ways to insert themselves into mainstream politics. In the aftermath of Jan. 6, they shifted their efforts to local politics, focusing especially on COVID safety protocols and school curricula. Hard-right organizations disrupted school board and city council meetings around the country and, in the process, created space for more extreme and bigoted voices. As a result, public servants have experienced a wave of threats that will likely continue as the country heads toward the 2022 midterms.

Meeting the challenge of the hard right

The antidemocratic hard right described in this report is a social and political movement that rejects equality and pluralism, and through its actions seeks to build a hierarchically ordered society in which certain groups of people hold more political, social and economic power than others. The hard right is authoritarian and reactionary, and very often conspiratorial, racist and nationalistic. Not all the groups and individuals that make up the hard right hold the same beliefs or embrace the same political strategies. But all espouse a view of society that is exclusionary, and generally target people of color, women, LGBTQ people, religious minorities, immigrants and non-Christians.

The SPLC tracks both hate groups and antigovernment extremist groups – which, combined, make up some of the most extreme elements of the hard right. Hate groups vilify others based on such immutable characteristics as race, religion and gender identity, while groups in the antigovernment movement believe that the federal government is tyrannical, and traffic in conspiracy theories that often malign the same marginalized communities that hate groups target. These groups often overlap and work alongside one another. Over the past year, they have converged around a willingness to engage in political violence, either inflict or accept harm, and deny legally established rights to historically oppressed groups of people.

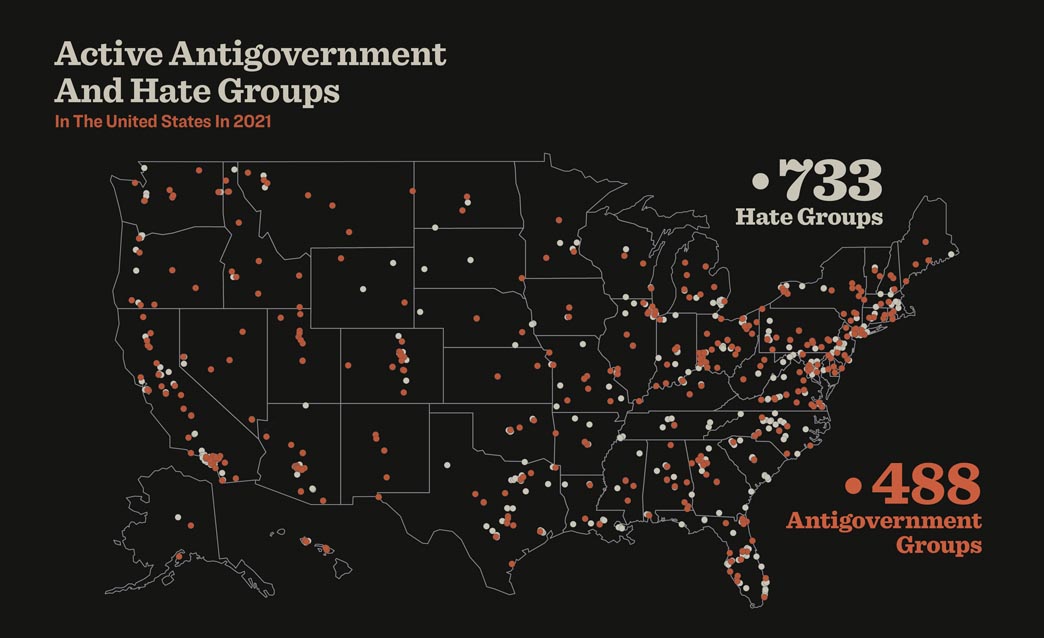

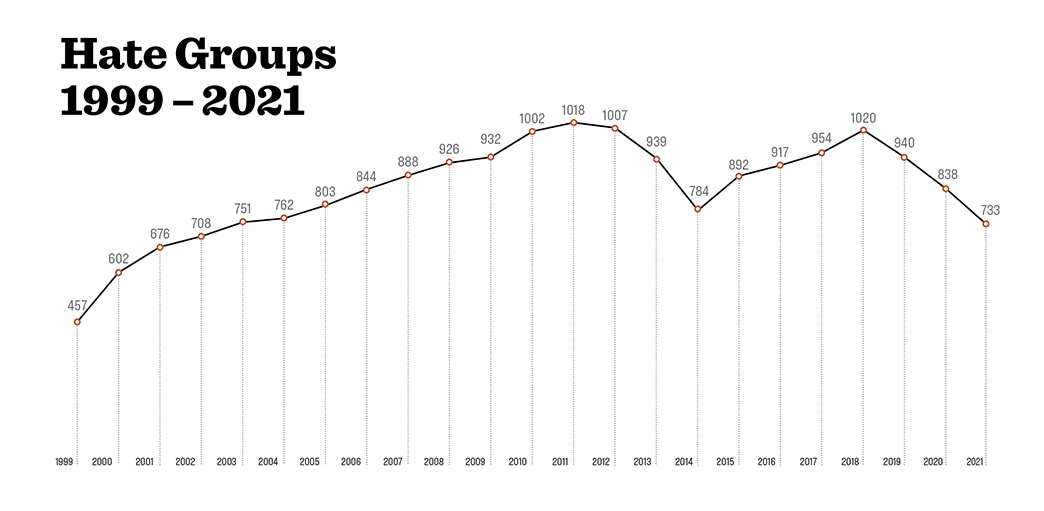

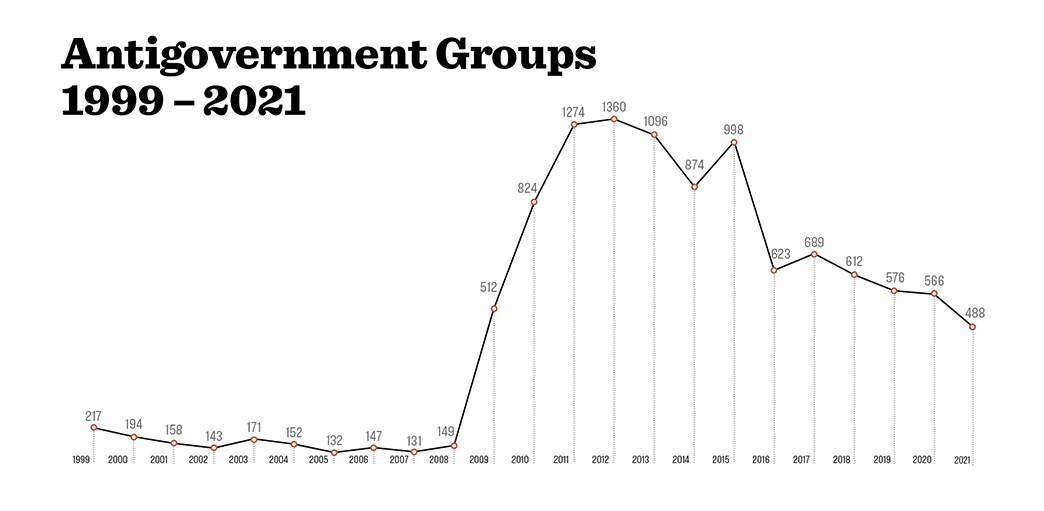

In 2021, the SPLC documented 1,221 active hate and antigovernment extremist groups across the United States. After reaching a historic high of 1,020 in 2018, hate group numbers have fallen for the third year in a row, to 733 in 2021. The number of antigovernment groups, too, has fallen from 566 in 2020 to 488 in 2021. Rather than demonstrating a decline in the power of the far right, the dropping numbers of organized hate and antigovernment groups suggest that the extremist ideas that mobilize them now operate more openly in the political mainstream. Roughly half of likely voters, for instance, believe that the Jan. 6 insurrectionists who were arrested and jailed are “political prisoners” — an idea that was promoted by such groups as the Proud Boys in the months following the siege and was then advanced by some Republican elected officials and conservative media pundits. Extremist organizing doesn’t need to take place in fringe hate groups when right-wing extremist narratives circulate widely, and their proponents hold real institutional and social power.

This does not mean the continued ascent of the hard right is inevitable. In 2020, the country gathered to protest in the name of racial justice in what, in terms of participants, was possibly the largest political mobilization the country has ever seen. The pandemic has wreaked havoc on communities vulnerable to health and economic instability, but people have also used the crisis as an opportunity to organize and build solidarity. Workers across the country and a variety of employment sectors are unionizing to improve pay and working conditions, and communities have organized to provide mutual aid. People, especially in the Deep South, are working to expand and protect voting rights, despite an onslaught of voter-suppression laws.

Pushing back against rising authoritarianism will require a holistic approach. To stop a movement that openly decries democracy, lawmakers need to reinforce democratic institutions — most immediately by protecting voting rights. The hard right is now a mainstream political movement, and traditional counterterror tools — including increasing law enforcement agencies’ surveillance and intelligence gathering capabilities — are not suited for blunting the movement’s growth. In addition, history shows they would likely lead to violations of Americans’ civil liberties. The country needs to address the threat of extremism as a social problem, which requires investment in social programs and public health-inspired prevention measures. With good public policy, significant investment from government and business, and on-the-ground community organizing, the tide can be turned.

Where extreme meets mainstream

The growth of a mainstream reactionary right-wing movement in 2021 is inextricably linked to the powerful racial justice movement that mobilized Americans in 2020. The movement for Black lives forced the country to reckon with the realities of systemic anti-Black racism and police violence. Its widespread resonance also ignited fear in the hard right, which mounted counter-efforts to maintain and strengthen white supremacy. Trump and other reactionaries demonized the movement, and painted Black Lives Matter activists, Democrats and the left broadly as an existential threat to the country. “The left-wing cultural revolution,” Trump said in a September 2020 speech, “is designed to overthrow the American Revolution.”

This backlash has historical precedent. During Reconstruction, whites who wanted to maintain their supremacy founded the Klan to intimidate newly emancipated Black people and violently perpetuate a system of racial subjugation rooted in slavery. In the civil rights era, white citizens, politicians and law enforcement worked together to fight the freedom movement with violence and an organized campaign of “massive resistance” to school desegregation. Repressive right-wing movements like this emerge during moments of social change and are, according to Chip Berlet and Matthew Lyons, two prominent scholars of the far right, “motivated or defined centrally by backlash against liberation movements, social reform, or revolution.” Or, as the historian Carol Anderson put it, “The trigger for white rage, inevitably, is Black advancement.”

The overwhelming majority of people arrested for their role in the insurrection had no formal ties to right-wing groups. They came from all over the country. The majority were employed. Most were in their 40s and 50s, and they mostly get their news from mainstream media. Among middle-aged, middle- and upper-class people, this illiberal political movement has found its footing and become thoroughly mainstream.

Another factor tied together the people who took part in the Capitol siege: “Counties with the most significant declines in the non-Hispanic White population,” a University of Chicago study found, were “the most likely to produce insurrectionists.” Later polling conducted by the same University of Chicago researchers found that, among Americans who believe the use of violence is justified to restore Trump to the presidency, almost two-thirds also believed that Black and Hispanic people in the United States “will eventually have more rights than whites.” Put another way, the hard-right movement that supports the insurrection is motivated in large part by a desire to maintain white political hegemony.

Fear of changes to the social status quo, in which white people hold a privileged place, has helped fuel the mainstreaming of the “great replacement” myth — a conspiracy in which white people are being systematically replaced by non-white immigrants at the hands of leftists, Democrats, “multiculturalists,” Jewish people and others. The myth is central to the white nationalist movement, which in 2021 included 98 hate groups. Since 2018, extremists inspired by the great replacement theory have committed terror attacks in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Christchurch, New Zealand; Poway, California; and El Paso, Texas. But as hard-right actors weaponize America’s demographic changes to instill fear and resentment, the myth has spread beyond terrorist manifestos and into American living rooms.

In 2021, Tucker Carlson, whose Fox News show is the most-viewed cable news program in the country, openly promoted the great replacement conspiracy. “In political terms, this policy is called the great replacement, the replacement of legacy Americans with more obedient people from faraway countries,” he said on air in September. His words opened space for others, including elected officials such as Rep. Matt Gaetz of Florida, who tweeted that Carlson was “CORRECT about Replacement Theory as he explains what is happening to America.” Officials in border states, where white nationalist and antigovernment groups have “intercepted” and interrogated migrants, have especially tried to ramp up fear of white replacement to undercut their political opposition. Democrats, Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick said on Fox News, are using immigration to “take over our country without firing a shot.”

In response to the elected officials and other public figures citing the great replacement theory, Vincent James Foxx, a white nationalist who helped organize the “Stop the Steal” movement, wrote on Telegram: “We are the mainstream now. Our message and worldview are inevitably the conclusions every conservative in the country will come to.”

The right’s embrace of violence

In February, the Arizona congressman Rep. Paul Gosar addressed a crowd at the America First Political Action Conference (AFPAC). The event, held annually, is hosted by white nationalist streamer Nick Fuentes, who stationed himself outside the Capitol on Jan. 6 and told his followers to “break down the barriers and disregard the police.”

“White people founded this country. This country wouldn’t exist without white people. And white people are done being bullied,” Fuentes told AFPAC attendees in his speech, immediately after the sitting Republican congressman spoke.

Gosar made news again later in the year when he posted a video to Twitter of an anime version of himself killing Democratic Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and attacking President Joe Biden. While Gosar was eventually censured by the House of Representatives for the tweet, his Republican colleagues shied away from condemning his actions. Only two voted in favor of the censure.

Gosar’s tweet and the Republican failure to respond are but one illustration of how much violent rhetoric and threats have been normalized on the right. Political scientists and historians have noted that, although political violence is certainly not absent in America’s history, this moment is unique because of the legitimacy that elected officials, as well as the former president, have lent to using violence as a political tool. “The elite endorsement of political violence from factions of the Republican Party is distinct for me from what we saw in the 1960s,” Pomona College political scientist Omar Wasow told The New York Times. “Then, you didn’t have — from a president on down — politicians calling citizens to engage in violent resistance.”

At his speech on Jan. 6, 2021, then-President Trump told his followers and the members of his party, “Our country has been under siege for a long time.” He said, “If you don’t fight like hell, we’re not going to have a country anymore.” Other Republicans have followed suit, suggesting only extraordinary solutions, outside the normal political process, are fit to meet the threat. Officials, including Rep. Madison Cawthorn, have cited the election fraud myth as evidence that violence could become inevitable: “You know, if our election systems continue to be rigged, and continue to be stolen, then it’s going to lead to one place, and it’s bloodshed,” he said at a North Carolina GOP event in August.

Republican voters, too, are shifting toward a greater acceptance of political violence. According to research conducted by the Public Religion Research Institute, 30% of Republicans, and 39% of those who believe the 2020 election was stolen from Trump, agree that “true American patriots might have to resort to violence in order to save our country.”

Perhaps no moment better illustrated the extent to which some Republicans tolerate and even encourage violence than the way the party celebrated the acquittal of Kyle Rittenhouse. The teenager, who was not known to have extremist ties at the time, but whom far-right extremists like the Proud Boys have since exalted as a “hero” and “saint,” killed two protesters and maimed a third at a 2020 racial justice protest in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Rittenhouse was acquitted after testifying that he fired in self-defense. “There is hope for this country,” Rep. Thomas Massie tweeted after learning the verdict. Others have made a show of vying to hire Rittenhouse as their intern, while the right-wing campus organization Turning Point USA treated him like a celebrity at their America Fest 2021 event. In a bizarre carnival-like atmosphere, Rittenhouse received a standing ovation as he strolled onstage for a panel discussion accompanied by pyrotechnics and his own theme song.

Proud Boys membership spikes

While the overall number of hate groups declined in 2021, some groups experienced rapid growth, as well as increased influence and access to the political mainstream. The most dramatic rise happened within the Proud Boys, a “Western chauvinist” men’s organization with a long history of violence. In 2021, the SPLC documented 72 active Proud Boys chapters across the country, up from 43 the year before. The rise in Proud Boys chapters is especially remarkable considering that at least 40 members of the group have been charged in relation to their role in the Jan. 6 insurrection. Their growth suggests the country has become alarmingly fertile ground for their brand of authoritarian politics.

The Proud Boys spent the Trump years hosting rallies around the country that often descended into violent riots. With a handful of exceptions, they faced little interference from law enforcement, giving the impression that they had the tacit approval of police. They built a vast organizational network and, when Trump told the group to “stand back and stand by” during the first presidential debate in 2020, they became a household name. Acting as Trump’s foot soldiers, roughly 100 Proud Boys descended on the Capitol on Jan. 6, and members of the group were among the first to enter the building during the siege.

Like other far-right extremists, the Proud Boys have shied away from large-scale protests in the aftermath of the Jan. 6 insurrection, especially those held in Washington, D.C., out of fear of attracting law enforcement attention. The group has continued to organize, however. According to research from VICE reporter Tess Owens, the Proud Boys attended at least 114 public events in 2021, largely targeting local governments and community institutions such as public schools.

As the larger political right riled up their base over issues including masking, vaccines and inclusive curriculums in schools, groups like the Proud Boys have latched on, winning supporters, building alliances across different interest groups and normalizing their place within mainstream right-wing spaces by entwining themselves in local political battles. They have attended and hosted rallies, menaced people at school board meetings and provided security at right-wing events. “Oh my goodness, thank God for the Proud Boys,” said a pastor whose anti-abortion event in Salem, Oregon, was guarded by members of the group.

This kind of local-level organizing has real impacts on communities and local officials, who are subjected to threats and harassment. While the Proud Boys have run a handful of candidates for local elected office, they primarily want to use their presence as a tool of intimidation. Explaining why the Cape Fear Proud Boys were attending a school board meeting in North Carolina, a member told a reporter, “If our presence escalates that pressure and makes it to the point where we become a distraction to conducting business and they just change the mask mandate so we go away, that’s a win.” Students are also targets of right-wing mobilization. In a suburb of Chicago, Proud Boys attended a November school board meeting to express their opposition to the school library’s inclusion of Gender Queer, a memoir written by a non-binary author. Members of the group taunted students who defended the book and accused one of being a pedophile. Students told a reporter at the Chicago Sun-Times that the Proud Boys’ actions were “unnerving” and “intimidating.”

In Nashua, New Hampshire, the school board began stationing police at its meetings after Proud Boys and members of the neo-Nazi group NSC-131 began to attend. “This is my fourth year on the board,” one member said, “and this is the first time we’ve needed to do this. It’s not good for our community.”

White Nationalist and Neo-Nazi groups continue to adapt

Even as the ideas that propel the white power movement gain more purchase among an increasingly authoritarian Republican Party, its constituent groups have faced organizational challenges, due in part to law enforcement pressure and civil suits.

After a series of deadly far-right attacks during the Trump presidency, the Department of Homeland Security recognized in a 2020 threat assessment that white supremacist extremists are, and will remain, “the most persistent and lethal threat to the Homeland.” The report, along with later statements by the Biden administration, marked a larger shift within law enforcement and intelligence agencies away from foreign terrorist groups, which became the single-minded focus of federal counter-extremism efforts following the 9/11 attacks.

As a result of the renewed focus on domestic extremism — which accelerated after the insurrection — the white power movement experienced a slew of arrests in the last two years. In fall 2021, two members of the white nationalist group The Base were sentenced to nine years in prison after they received a terrorism enhancement to gun charges stemming from 2020. Another was sentenced to 20 years for his role in a conspiracy to murder a couple involved in antifascist activism.

Partially as an attempt to evade authorities and antifascist infiltrators, neo-Nazi groups, whose numbers dipped from 63 groups in 2020 to 54 in 2021, organized in more decentralized fashion. Prominent voices in the movement now encourage members of neo-Nazi online communities to maintain anonymity and congregate in diffuse online communities rather than join public-facing groups with names and membership vetting procedures. Extremists not associated with a defined group have still been arrested, showing the strategy has returned mixed results.

In addition to attracting attention from law enforcement, the energy of the white power movement was dampened by the outcome of the Sines v. Kessler trial, a civil suit brought by Integrity First for America against the organizers of the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. On Nov. 23, 2021, jurors found all the defendants liable on a number of charges, including civil conspiracy, under Virginia state law. Combined, they face $25 million in damages.

Though the increased attention of civil authorities has created major challenges to the white power movement, it’s clear that the criminal legal system, on its own, cannot adequately address the problem of far-right extremism. A large subset of the movement remains concentrated on influencing mainstream politics, and nearly every indicator suggests the political ground is fertile to their appeals unless diverse communities working together build resiliency through prevention, organizing and education.

Some white nationalist organizations, such as Nick Fuentes’ America First Foundation, want to exert power over the GOP and convince its members to openly embrace white nationalism. Others are attempting to build infrastructure to challenge mainstream institutions, including the National Justice Party (NJP). Founded in 2020 by several longtime activists in the white power movement, NJP has become a hub for the movement. The group hosts meetings throughout the year where representatives from a number of white nationalist groups can come together and collectively organize. An October 2021 meeting gathered about 150 attendees.

One of those groups is Patriot Front, which has 42 chapters nationwide. In 2021, Patriot Front held multiple “flash” demonstrations around the country and, according to leaked internal communications, defaced George Floyd and Black Lives Matter murals. Patriot Front, like many extremist groups, at times uses mainstream social media to spread their propaganda. During a December demonstration in Washington, D.C., that included about 100 members marching through the National Mall, a Patriot Front member created a fake Twitter account to bring their action to mainstream attention: “HAPPENING NOW: About 500 men with riot shields are marching in #WashingtonDC,” the account tweeted, gaining more than 1,000 retweets.

Extremists easily get around bans on social media platforms, often simply creating new usernames and continuing to post. They also find ways to make algorithms work to amplify their content, including using specific words or hashtags repeatedly to make them appear under the “Trending on Twitter” section. During the Jan. 6 insurrection, for instance, members of the far right used Twitter to spread the lie that antifa attacked the Capitol — a conspiracy later repeated on the House floor. More broadly, platforms such as Twitter and Facebook have failed for years to adequately enforce their own terms of service. Both companies operate under a libertarian ethos, allowing white supremacist and other hateful and dangerous content on their platforms. They have invested inadequate resources into meaningful content moderation despite repeated promises to do so, and they tend to remove extremist content or individuals only after heavy public pressure.

Hate groups and other extremists do not solely rely on mainstream social media platforms to spread their message — they are increasingly using “alt-tech” platforms that are often advertised as “free speech” alternatives to places like Twitter and Facebook. On these platforms, users don’t have to worry about content moderation. These include video platforms like Bitchute and Odysee and social media sites like Gab. The startup Chthonic Software helped create a monetized streaming site for Nick Fuentes and other extremist livestreamers after many were banned from other sites in the aftermath of Jan. 6.

Gab has for years been a haven for racist and antisemites. The man who is charged with killing 11 people at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 2018 was a user and posted on the site immediately before the attack. In the past year, Gab CEO Andrew Torba has expanded the services offered on the platform to create what he calls a “parallel society.” “At Gab when we recognize a problem in the world, like Big Tech censorship and the anti-White, anti-Christian, and anti-American woke economy, we don’t just sit around and complain about it like our useless politicians do,” Torba posted to Gab’s website in June. “We take action and start building.” The company recently launched an ad platform and says it will soon offer a payment processor. The services Gab, Chthonic and others offer suggest that the white power movement is building increasingly resilient online services, which can allow extremists to spread and monetize their content while remaining impervious to public pressure or government regulation.

The Antigovernment Movement takes a hit, but gets back up bruised and battered

The number of antigovernment groups decreased in 2021, down by 79 from 2020 for a total of 488 in 2021. This trend has held fast since antigovernment group numbers peaked in the 2010s with the rise of the tea party movement. Like hate groups, the current decrease in organizational numbers does not reflect a lack of popularity of antigovernment ideology, nor a significant decrease in the level of supporters and participation in movement activities. The primary grievances that underpin the movement – in particular, distrust of the federal government and an absolutist take on gun rights – are widespread within the United States. Trust in the federal government has been declining over the last two decades and, in 2021, only 39% of Americans said they trusted the federal government to handle domestic issues. While Americans support passing stricter gun laws, a powerful minority has pushed states to continue easing restrictions on firearms and sowed the conspiratorial belief that the government could someday confiscate Americans’ guns. Gun sales in 2020 and 2021 reached historic levels, further setting the stage for political violence.

While the antigovernment movement has always maintained some national communications infrastructure, including online forums, social media helped build national organizations like the Oath Keepers and helped to popularize antigovernment imagery like the Gadsden Flag. During his presidency, Trump further legitimized the movements, particularly as states around the country implemented public health measures in the first months of the pandemic. “LIBERATE MINNESOTA!,” “LIBERATE MICHIGAN!” and “LIBERATE VIRGINIA,” he tweeted in 2020, adding to the last tweet: “And save your great 2nd Amendment. It is under siege!” This kind of rhetoric bolstered the power of the movement and read like a call to arms for extremists.

The Jan. 6 attack was the most public moment for the antigovernment movement since the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995. Like Oklahoma City, the violence of Jan. 6 has brought new pressure on the movement, but that pressure has not necessarily reduced its influence. Over 700 individuals have been charged with a variety of crimes for their participation in the insurrection, including 22 members of the Oath Keepers and at least four members of the Three Percenters. Eleven Oath Keepers and the group’s founder, Stewart Rhodes, have been charged with seditious conspiracy for their role, a rare and notably serious charge.

Following Jan. 6, the antigovernment movement has faced greater scrutiny by the public, media, law enforcement, policy makers, tech and social media companies, and lawmakers. That scrutiny, along with the deplatforming on Facebook of some 2,000 antigovernment associated pages in fall 2020, has forced groups in the movement to reorganize. As a result, their activity has become more dispersed and focused on localized activities. After the insurrection, Oath Keeper chapter head Doug Smith said, “As far as Jan. 6, I will never attach my name or the men in this state to Oath Keepers again.” The North Carolina chapter voted to unaffiliate and break with the national organization.

Since the insurrection, factions of the far right have coalesced around several hot-button issues with widespread right-wing support, including refusing to acknowledge Biden’s win. Issues fueling antigovernment extremists include organizing against what they perceive to be adoption of critical race theory (CRT) in public schools, against vaccine and mask mandates, and in opposition to immigration.

The antigovernment movement couches its extremist ideas under the language of patriotism. Ammon Bundy’s People’s Rights, in particular, has made use of this rhetoric. Bundy is well known for engineering armed standoffs in 2016 at the Malheur Refuge in Oregon and, in 2014, on federally leased lands in Nevada. In 2021, People’s Rights activists held a variety of small-scale demonstrations for individual grievances over taxes, property rights and natural resource availability. Throughout 2020 and 2021, Bundy organized a series of stunts and acts of political intimidation while purposefully disobeying COVID-19 public health measures that resulted in his arrest. Bundy, like several antigovernment activists in the second half of 2021, also began a campaign for political office in Idaho for the 2022 midterm elections.

In the Southwest, militias and other extremists have collaborated to set up camps in the desert targeting migrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. During 2021, hard-right extremists continued to harass humanitarian aid groups, some using their relationships with border patrol agents to circumvent and legitimize their vigilante activities. The activities of militia groups have gone unchecked, and groups continue to illegally detain migrants.

After four years of national alignment with the Trump administration, antigovernment extremists have returned to their bread-and-butter focus on attacking local democratic institutions and rallying against the U.S. Federal Government and tribal governments at the local level. The focus has heavily targeted local public health boards, school boards and elections administration officials.

The John Birch Society and QAnon enthusiasts have also peddled anti-vaccine misinformation and anti-mask propaganda, formed protests and rallies, and caused disturbances in front of hospitals and public officials’ homes. Conspiracy propagandists have found a niche audience with COVID-19 vaccine skeptics, using existing antigovernment mistrust, corporate skepticism and a long historical relationship with a growing natural-health sector to push the false ideas of vaccine danger. Other COVID-19 conspiracy theories are extensions of previous iterations of falsities about government population control, often rooted in fears of demographic shifts, and coded antisemitic conspiracies about a vaccine push by a cabal of nefarious actors.

Organized by the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association (CSPOA) and Protect America Now (PAN), many constitutional sheriffs have promoted COVID-19 conspiracy theories and refused to enforce health guidelines enacted by their lawmakers. More than 40 sheriffs attended a CSPOA event in Texas in February, and three county commissions purchased lifetime memberships in the association. CSPOA leader Richard Mack spent 2021 touring the country recruiting sheriffs and speaking at events, alongside QAnon adherents, antisemites and sovereign citizens. PAN also signed onto a letter to the president about the border promoted by SPLC designated anti-immigrant hate group Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR).

On many occasions, promoters of a wide variety of conspiracy theories and antigovernment ideologies have converged on single events to network. This has included the Reawaken America and Arise USA event tours featuring a mix of known antigovernment extremists, alternative health leaders, politicians and political advisors, and activists in the Patriot movement associated with the religious right. Many of the hallmark antigovernment events and tours featured Jan. 6 participants and organizers and perpetuated the “Big Lie” of a stolen election. These events supported the many regressive policy changes to voting rights that stained state Houses around the country in 2021.

The coalescing of QAnon adherents with sovereign citizens, constitutional sheriffs and militia members, along with conspiracy-minded anti-maskers and anti-vaxxers, has produced an environment where groups can openly recruit and market their ideas to each other and the general public.

Mainstream hate reorients without the White House in its pocket

Hate groups continue to permeate mainstream society and politics with bigoted anti-LGBTQ, anti-immigrant, and anti-Muslim ideas and policies. These groups were in recovery mode following Trump’s loss, as they saw some rollbacks by the Biden administration of the most flagrantly anti-immigrant Trump policies, such as the attempt to restrict entry into the U.S. from a range of majority-Muslim countries.

SPLC documented 50 anti-Muslim groups active in the U.S. in 2021. They represent a sophisticated, well-funded network dedicated to vilifying Muslims and their faith. This network spans from more established anti-Muslim think tanks operating inside the Beltway to localized groups focusing on state and county issues. Key figures in the network, such as Brigitte Gabriel and Frank Gaffney, remain politically connected and influential. One of the largest anti-Muslim organizations, ACT for America, decreased its chapters numbers once again. Many of the group’s chapters have broken off to form independent organizations, such as AlertAmerica.News, Last Chance Patriots, Red-Green Axis Exposed and G416 Patriots.

Some groups moved from focused anti-Muslim ideology to more generalized hate issues and conspiracies about inclusive education, the Black Lives Matter movement and COVID-19. In the last quarter of 2021, anti-Muslim groups leaned into their bigotry as the U.S. troop withdrawal from Afghanistan resulted in a new round of refugee resettlement in communities around the U.S.

The LGBTQ rights movement gained an ally in the Biden-Harris administration and continues to see positive movement at the local and business level, but hate groups mobilized in 2021 to push back and attempt to advance anti-LGBTQ bigotry. SPLC documented 65 groups in 2021 that were focused on regressive state legislative policies, pushing harmful conversion “therapy,” vilifying trans people, banning books that were LGBTQ-welcoming, and taking on school boards on anti-LGBTQ topics. Many new locally focused “parent” organizations leaned into segregationist language of “parent choice” to oppose masking, vaccination and LGBTQ rights. Groups like Mass Resistance coordinated local action targeting school boards and libraries in anti-transgender attacks.

These modern reactionary campaigns are modeled on efforts from the 1980s and 1990s, when the right used fear of the HIV epidemic to demonize the LGBTQ community in an attempt to kneecap their movement for equal rights. In the previous decades they passed anti-LGBTQ public school curriculum laws, and today these groups are advocating book bans and attacking LGBTQ educators. Likewise, the John Birch Society, which opposed school desegregation, continues with the same antigovernment communist conspiracies, this time using them to oppose COVID-19 masking and other “culture war” issues to mobilize parents into hard-right political action. John Birch Society founding board member Fred Koch’s legacy continues, with his descendants’ philanthropic organizations engaging in astroturfing anti-CRT campaigns across the country and trying to hide their national agenda and make it look like it originated locally.

Anti-immigrant hate groups also reoriented their strategy to state government and local elected officials, with a focus on attorneys general and sheriffs in U.S. Southern border states. Dan Stein, president of FAIR, stated it clearly: “In this environment, our state legislatures and governors are the last line of defense.” Ken Cuccinelli, a former Virginia Attorney General and Trump Homeland Security official, recently published a policy brief at the Center for Renewing America on the strategy and concluded, “Given the federal government’s dereliction of duty, it is now incumbent on governors and states to fill the void and do what federal officials and lawmakers refuse to do: end the invasion at the U.S. southern border and restore both order and sovereignty.”

Several high-ranking Trump administration officials filled staff positions at various anti-immigrant hate groups. For example, Tom Homan, Trump’s acting director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement from 2017 to 2018, and Mark Morgan, Trump’s acting director of ICE and U.S. Customs and Border Protection, are both senior fellows at FAIR.

The implications of these hard-right activities are grave. White supremacy perpetuates systemic racism. As a result, communities of color, LGBTQ people, immigrants and refugees, and religious minorities face continued threats, intimidation, violence and bias. Nearly one out of every four Jewish people in the U.S. reported experiencing being a target of antisemitism in the past year. Advocacy groups for both Muslim and Jewish American people reported a spike in hate crimes, harassment, bullying and discrimination. In New York, reports of subway bias incidents that targeted Asian Americans increased 233% from 2020. The Human Rights Campaign called 2021 the deadliest year on record, documenting that at least 57 transgender and gender non-conforming people were killed in the U.S.

Conclusion

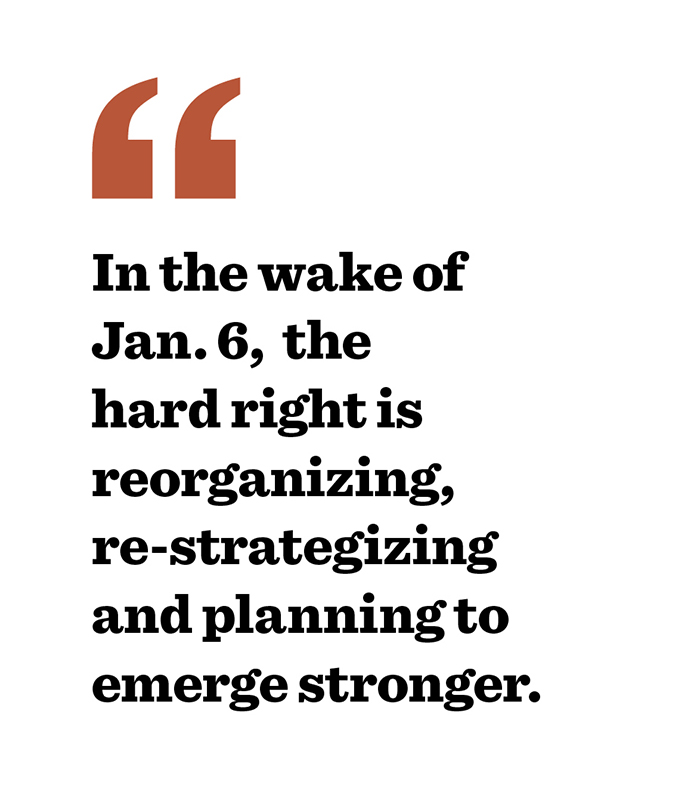

Jan. 6 should be recognized for what it was: a full-on violent assault on democracy that showcased the strength of the hard right. In the wake of that day, the hard right is reorganizing, re-strategizing and planning to emerge stronger. Throughout 2021, the hard right hit the streets across the U.S., blocked important policy, attacked democratic institutions, engaged in violence and energized their base of supporters. The 12 months that followed Jan. 6 showed beyond a doubt that they will not go quietly.

Such institutions as SPLC, the media, Congress, the Justice Department and law enforcement are working to hold accountable the actors and instigators of Jan. 6 and those that continue to perpetrate harm to communities and democracy. This accountability is incredibly important and can have a real impact, but it will be only temporary if it becomes too focused on individual criminal acts. The problems are societal and require holistic solutions.

Historically, the United States has relied heavily on law enforcement, intelligence agencies and the criminal legal system to address social problems. That power has repeatedly been abused and disproportionately wielded against progressive activists, immigrant communities, communities of color and religious minority groups. After the Sept. 11 attacks, intelligence and law enforcement agencies engaged in racial profiling, spying on Muslim communities in the name of national security. Now, there are calls to use the same set of tools against white supremacists, and even to expand counterterrorism tools by creating a domestic terrorism statute. In fact, the government already has the power to effectively prosecute extremists, a fact supported by recent convictions against white supremacists and the charges brought against more than 700 people connected to the insurrection.

A national security-centric approach will never be able to blunt a mainstream authoritarian political movement. Accountability matters, and there will be legal consequences for those that attempt to overthrow the government, threaten democratic institutions and inflict harm on others. But the United States must also look for ways to build a more resilient democracy. Communities and governments need to adopt a public health approach to preventing extremism by engaging communities, mental health experts, social workers and, especially, people involved in the day-to-day lives of young people.

Even more, a reinvigorated vision of a more inclusive democracy is necessary, one that creates a stark alternative away from the destructive path of the hard right. That means expanding and protecting access to voting, creating legislation to protect people who face discrimination, promoting civics education and teaching students an anti-racist curriculum, and ensuring all Americans have healthcare, housing and other vital services so they can lead safe and dignified lives.

History tells us that the threat is real, but it also reminds us that we can turn the tide.

In this section

• ‘YouTube as we know it is over’

• Funding hate by going live

• Livestreaming’s role in community building

• ‘Where things fall through the cracks’

By Hannah Gais

Throughout 2021, right-wing extremists increasingly embraced livestreaming technologies as their preferred tool for organization, fundraising and propaganda.

The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) has tracked extremists from a range of far-right ideologies gravitating toward a plethora of livestreaming video platforms. In part, this pivot to live video content mirrors the medium’s popularity among mainstream social media users, many of whom have turned to livestreaming platforms for entertainment. But it also reflects a tactical shift among extremists toward sites that provide an infrastructure for fundraising, promoting in-person events and preserving an archive of their work.

“Extremists and hate groups are typically early adopters of new technology, particularly anything that can be used for propagandizing, recruitment or harassment. With video livestreaming, they have found a low-cost, engaging way to get their message out, and unfortunately, they are making money at it too,” Megan Squire, an Elon University professor and SPLC senior fellow, said in an interview.

Livestreaming content presents challenges to stopping the spread of hateful content online. It is ephemeral – meaning content is not always automatically saved on a site, so a streamer may choose to remove a stream with content that violates a platform’s terms of service after a broadcast and before site moderators can act. In addition, some sites rely on users to report egregious live content. In other words, even if a video is flagged for review, moderation teams may not act until a livestream has already concluded. Finally, a constellation of “alt-tech” sites, some of which were built by and for the far right, operate with minimal or no content moderation, ensuring that extremists can continue to raise money and promote their activities unimpeded.

‘YouTube as we know it is over’

While people have been broadcasting live video content over the internet since the 1990s, today’s decentralized right-wing extremist livestreaming ecosystem is a reaction to policy changes on mainstream platforms such as YouTube and Twitch.

In late 2019, in response to real-world violence and charges that YouTube’s recommendation algorithm was propping up extremist content, the popular video streaming site began taking a more systematic approach to cracking down on violent content and hate speech on the platform. Far-right extremists began gravitating toward so-called “alt-tech” sites. While the “alt-tech” ecosystem is not exclusive to the radical right, in this case the term refers to platforms that provide a haven through limited or no content moderation for those users who have been, or at least risk being, locked out of mainstream social media sites for violating their terms of service, usually on hate speech.

“YouTube as we know it is over. They will burn themselves to the ground to ruin alt voices from getting out. Go to alt sources now,” Red Ice TV, a prominent white nationalist site, tweeted on Dec. 3, 2019, less than two months after YouTube banned the show permanently.

If someone is looking for a substitute for YouTube, they can turn to a variety of alternative platforms, some of which have explicitly marketed themselves as “free speech” havens. There’s DLive, a youth-targeted gaming site; Rumble, the Peter Thiel-funded video streaming site popular with pro-Trump conservatives; Trovo, another gaming-focused video platform; Brighteon, one of the platforms that a coalition of state attorneys general listed in early 2021 in a letter for its wealth of medical disinformation around the COVID-19 pandemic; or Odysee, a video streaming site that allows creators to monetize their content through cryptocurrency. For more options for monetization, creators can turn to SubscribeStar, a clone of the subscription service Patreon, or Entropy, a software that works in conjunction with YouTube or other livestreaming platforms to provide an alternative space for livestreamers to raise money off their work and interact with viewers. A handful of extremist creators have launched their own platforms as well.

Among the broader far right, the popularity of livestreaming is reflected in its presence at events. SPLC reviewed criminal complaints against alleged participants in the Jan. 6 insurrection and found references to a variety of platforms with livestreaming capabilities, including Periscope, DLive, Twitch, YouTube, Odysee and others. Hatewatch, the publishing arm of SPLC’s Intelligence Project, documented at least five DLive accounts streaming from the Jan. 6 “Stop the Steal” rally-turned-insurrection.

“Every large-scale or even medium-scale [demonstration]: political events, anti-lockdown demonstrations – they’re all going to have a livestreaming element,” Ciaran O’Connor, an analyst at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, told SPLC in an interview.

“Content is king for these people. That’s what drives a lot this: they just want to create content that they can share online, they can get donations and views off of, [and] they can share later on as clips,” he said.

Funding hate by going live

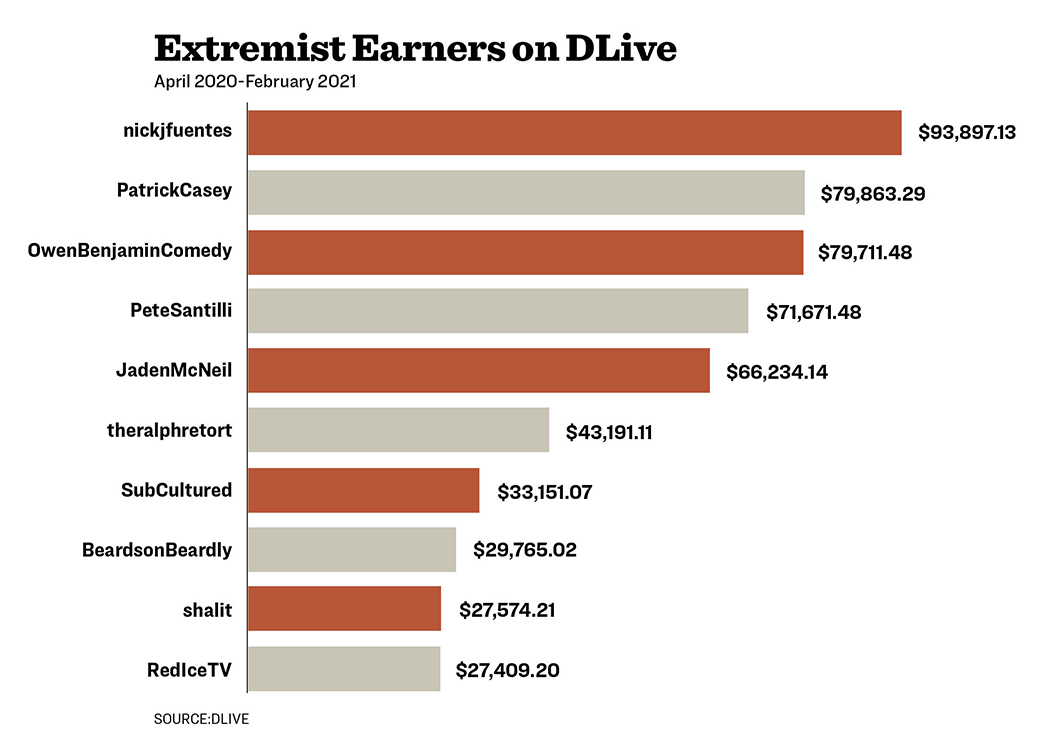

“Alt-tech” platforms generally don’t command the same audience size – and, thus, the same access to possible donors – as YouTube and Twitch. Still, they have provided a fruitful fundraising outlet for extremists, some of whom have netted annual earnings in the low six figures off streaming alone.

One of these is Nick Fuentes, a white nationalist livestreamer and “Stop the Steal” proponent whose “America First” show has aired on a variety of platforms since fall 2017. As Hatewatch reported in late 2020, Fuentes was one of the top earners among a pool of 56 right-wing extremists on the youth-targeted platform DLive, yielding an average of $326 per day – an amount equal to a yearly salary of $119,000 – between April and October of 2020. Following Trump’s electoral loss and Fuentes’ involvement in the “Stop the Steal” movement, Fuentes increased his average to $600 per day on DLive, according to data from SPLC senior fellow Squire. On Jan. 9, 2021, DLive banned him from the site, along with several other users who either entered or were outside the Capitol during the insurrection.

Other right-wing extremist livestreamers have turned to SubscribeStar, a subscription-based site. Alex Kaplan, a senior researcher at Media Matters for America and the author of a December 2021 report examining 19 SubscribeStar accounts associated with far-right extremists, told SPLC in an email that the platform “has allowed [the far right] to raise significant amounts of money – while also profiting off of their content.” (SubscribeStar takes a 5% cut, at least, of users’ earnings.) In total, Kaplan found that these 19 accounts raked in nearly $29,000 a month. The group’s top earner, the QAnon-supporting video show SGT Report, made at least $4,472 a month through the site, roughly equivalent to a $54,000 yearly salary. Others included multimillionaire conspiracy theorist and Infowars founder Alex Jones ($4,261 per month); Red Ice TV ($3,910 per month); Vincent James Foxx, a Fuentes associate and former propagandist for the white nationalist street-fighting club Rise Above Movement ($3,346 per month); and Owen Shroyer, an Infowars host who was arrested on charges related to his alleged participation in the Capitol insurrection ($1,950 per month).

Unlike buying merchandise or a subscription, livestreaming platforms encourage engagement between donors and creators. On YouTube, DLive, Trovo, Odysee, Entropy and the like, users can comment and donate in real time during a stream. Scholars have pointed to a reciprocal relationship between donors and content creators, particularly regarding the role donations can play in influencing content. Becca Lewis, author of a 2018 report on right-wing networks on YouTube, noted that audience feedback through the site’s “super chats” – where viewers could comment on streams and donate in real time – could encourage content creators to read shocking or offensive statements on screen. Likewise, Squire observed in a 2021 paper focused on DLive that large-scale donors could take on a reputation of their own within a particular livestreamer’s fanbase. For instance, donors may be granted chat moderation privileges or unique shoutouts on a particular stream.

Livestreaming’s role in community building

As with podcasts, the extreme right has used livestreaming to promote events, propagate new ideas, network across and within ideologies, and above all, build a community. Researchers pointed to the intimacy livestreaming allows as crucial to its appeal.

“Creators get to speak to audience members in real time, over great spans of time, and audiences frequently get to interact directly with the creators,” Lewis, the author of the 2018 report on YouTube and a Ph.D. candidate at Stanford University whose work focuses on online political communities, told SPLC in an email. “This close dynamic is important for all creators trying to make a living from audience subscriptions and donations, but it’s especially important for white and male supremacist creators, who are also trying to impart their extremist messaging to their audiences.”

These close-knit communities can, in turn, ensure that a livestreamer’s messaging proliferates across platforms. O’Connor pointed to Paul Miller, a neo-Nazi known as “Gypsy Crusader” online, who recorded himself threatening and spewing racist slurs at users on the video chat app Omegle. Even though Miller’s career as a livestreamer spanned less than a year, O’Connor noted, his fans continue to share clips of his material on a slew of social media sites, including mainstream ones like TikTok.

These flourishing fanbases not only benefit extremists in terms of their reach, but they also make it possible for some to harness their own e-celebrity to hold real-world events or launch their own organizations.

In spring 2021, livestreamer Owen Benjamin, a self-styled antisemitic comedian who once claimed the Holocaust was Hitler’s effort to “clean [Germany] of parasites,” purchased a 10-acre lot of land in rural Idaho that he’s pitched as a “refuge” for his fans. Benjamin began fundraising for the compound in 2020, according to The Daily Beast, at which point he encouraged his supporters, who call themselves “bears,” to donate to the cause in exchange for camping rights. Had Benjamin been able to secure funds for a 200-acre piece of land, he told Lana Lokteff of Red Ice TV on Jan. 4, he had discussed doing “tactical training courses for donors.”

Likewise, Fuentes used his livestream fandom to publicly launch his own nonprofit political organization in early 2021. In the days before his annual America First Political Action Conference (AFPAC) – which is held each year alongside the more mainstream Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) – Fuentes announced that he would be spearheading the America First Foundation, a 501(c)4 organization. Such groups collect donations like a traditional nonprofit, but they have a wider latitude to engage in political activity such as lobbying and electioneering.

‘Where things fall through the cracks’

The prevalence of livestreaming comes with its own set of unique challenges to researchers, journalists and the tech companies responsible for moderating hateful content.

Researchers pointed to the challenges of moderating and monitoring livestreaming content. These ranged from the length of broadcasts – some of which can be upwards of three hours long – to the technical shortcomings of the platforms involved. Jared Holt, a resident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab whose work focuses on domestic extremism, told SPLC that livestreaming has long been “a place where things fall through the cracks.”

“Moderating live video content has often proved challenging for social media platforms since the content is being produced in near-real-time and can often be changed or removed after a stream to try to avoid would-be automated moderation against their channels. This content strategy also creates additional, though not impossible, challenges for researchers focused on hate movements,” Holt said.

Most platforms also depend on users to report egregious content in livestreams. This reliance on user-generated reports has already had disastrous consequences. In 2019, white supremacist terrorists in Christchurch, New Zealand, and Halle, Germany, used Facebook Live and Twitch, respectively, to broadcast their attacks in real time and rack up thousands of views. In the case of Christchurch, Facebook said in a statement posted March 18, 2019, that it received its first user report 29 minutes after the attacker, Brenton Tarrant, began livestreaming. Before Facebook took down the original video, it was viewed around 4,000 times.

Certain “alt-tech” platforms may not even offer a mechanism for reporting content – and even if they do, they may choose to overlook extremist activity. In May, The Guardian reported that an executive at Odysee told moderators that a “Nazi that makes videos about the superiority of the white race” was not enough to warrant removing content from the site. And some tech platforms even, directly or indirectly, encourage or facilitate extremism. As Hatewatch reported in December, an executive from Entropy announced he had constructed a custom piece of software for Fuentes, the white nationalist “Stop the Steal” proponent, after Entropy’s payment processor requested the company cut ties with him.

“As long as there are platforms that allow some form of monetization and either refuse to enforce their rules or do not care about who is using their platforms, white nationalists and other extremists will continue to have homes to fund their hate and conspiracy theories,” Alex Kaplan, the author of the Media Matters report on SubscribeStar, told SPLC.

But even with mainstream tech companies that have been receptive to criticisms of their handling of extremist content, researchers suggested that platforms’ moderation policies should be considered dynamic.

“We need to view tech company content policies as an ongoing, evolving process. That is, there will never be a point where companies reach a ‘sufficient’ policy approach and can rest on their laurels,” Lewis told the SPLC.

“Online extremists are constantly changing tactics, and tech companies will have to constantly keep up,” she added.

By Hannah Gais

Nick Fuentes, a white nationalist livestreamer and proponent of the anti-democratic “Stop the Steal” movement, spent much of 2021 jumping from one streaming platform to another following a ban from the youth-targeted streaming platform DLive in the wake of the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol.

On Jan. 9, 2021, three days after Fuentes told insurrectionists to “keep moving towards the Capitol” and “break down the barriers and disregard the police,” DLive announced it had banned Fuentes, and several others, from the platform on the basis of “inciting violent and illegal activities.” Prior to his DLive ban, the Southern Poverty Law Center Intelligence Project’s publishing arm, Hatewatch, reported that Fuentes was one of the top earners on the platform, on track to earn a salary of $118,000 per year. During the “Stop the Steal” protests in late 2020 and early 2021, Hatewatch learned that Fuentes received $43,822.86 in donations on DLive.

Fuentes’ efforts to construct a viable alternative platform following his DLive ban illustrates the hurdles right-wing extremists face after deplatforming. (“Deplatforming” refers to the action of tech companies stopping a person or group, particularly extremists, from using their services.)

“This has been the hardest year of my entire life,” Fuentes said on a Dec. 23, 2021, livestream, referencing these struggles. “We started out the year with everything I had built totally destroyed – the financial aspect of it, the streaming aspect of it, and even the infrastructure on the business side.”

SPLC tracked Fuentes’ activities after DLive banned him from the platform and found that he used a variety of tactics to keep his weeknight show, “America First,” up and running.

• On Jan. 11, 2021, Fuentes announced on Telegram that he had been working “around the clock” to launch his own streaming site in the immediate aftermath of the DLive ban. Due to technical issues, Fuentes and his team were unable to stream his show on the new platform until Jan. 15.

• The independent platform didn’t last, however. On Jan. 18, SPLC identified that Fuentes was using YouTube to stream his show, even though the video streaming site had banned him on Feb. 14, 2020. Through its examination of his site’s source code, SPLC determined that Fuentes had managed to return to YouTube. When SPLC reached out to YouTube on Jan. 20, 2021, a representative said they had terminated multiple channels for attempting to circumvent Fuentes’ ban from the platform.

• That same day, Fuentes gave a special shout-out to members of the tech team that had supported him through his efforts to find an alternative to DLive. As Hatewatch reported in November, among those Fuentes credited with providing technical support were, according to Hatewatch research and analysis, Simon Dickerman, who appears to have longstanding ties to white power circles online, and Michael Zimmermann, the then-information technology director of the Trump-tied conspiracy site Infowars.

• By mid-February, Fuentes’ team announced they were beta testing his new streaming platform. Though he remained the sole user of the site for several months, Fuentes rebranded his custom livestreaming platform as cozy.tv in mid-October.

• Fuentes continued to rely on an external platform, Entropy, to process donations and provide a chat for users during his livestreams. But as Hatewatch reported in December, Fuentes announced during a Nov. 29 broadcast of “America First” that Entropy’s payment processer forced the company to drop him as a client. Emmanuel Constantinidis, founder and CEO of Chthonic, the company that owns Entropy, reassured users of his software that they had “built [Fuentes] a replacement.” In a statement posted on the messaging app Discord, Constantinidis added, “It’s a complicated story, but sufficed to say we won’t leave anyone out to dry.”

Fuentes’ journey reflects the hurdles many right-wing extremists face when it comes to navigating the “alt-tech” ecosystem. As his brief return to YouTube demonstrates, deplatformed extremists still favor mainstream social media sites for their ease of use and audience. Above all, Fuentes’ month-and-a-half-long struggle to set up a viable long-term streaming alternative demonstrates the real costs of deplatforming, in that it not only strips them of their ability to fundraise but forces them to redirect income to find new ways to keep hate online.

In this section

• ‘Lemons to Lemonade’ with the BTV Clean Up Crew

• ‘Voices of Love and Unity’ for Afghan Refugees

• Seeding Freedom in the Mississippi Delta

• ‘We have to mobilize together’

• Next steps

Despite its challenges and tumult, 2021 was also a year marked by the actions and strength of individuals, organizations and communities across the United States who met the moment. Whether they’ve been working towards progress for decades or have recently organized to confront new manifestations of hardship and bigotry, their resilience remains steadfast. As we enter 2022, with political division and public health concerns at the forefront of our collective conscious, we’re seeking to highlight some of those individuals and organizations, as well as the coalitions they have helped build to support their communities. While those featured below continue to carry imperative work forward, we also aim to elevate the need for the equitable dissemination of support and resources.

Direct Grassroots Action: ‘Lemons to Lemonade’ with the BTV Clean Up Crew

By Lydia Bates

“If we believe in a community at all … [we] have to believe that our neighbors feel loved and welcomed,” explained a founding member of the BTV Clean Up Crew, based in Burlington, Vermont. This belief is what keeps the Clean Up Crew motivated as they confront hate and extremism in their community.

Founded in July 2019, the BTV Clean Up Crew works to remove bigoted stickers and flyers posted around the area by hate groups. Communicating via encrypted and secure messaging platforms, the grassroots coalition of community members identifies areas where hateful messages have been posted and organizes expedient removal.

Prior to COVID-19 precautions, group members spent weekends removing hateful material and picking up roadside trash. Since the onset of the pandemic, their activities have become more ad hoc, resulting in the removal of over 230 hate stickers and flyers in 2021.

The hate group that most frequently posts flyers and stickers in the Burlington area is a white nationalist group called Patriot Front. In a year when the flyering efforts of Patriot Front have increased elsewhere in the country, the Clean Up Crew reports that “in the aggregate, [the number of incidents] has gone down” in the Burlington area.

The group’s fundraising model has much to do with that decline. Each month, the Clean Up Crew tallies the number of hate stickers they’ve removed. They then crowdsource donations from Facebook followers who pledge a monetary amount per sticker to a local nonprofit of the Crew’s choosing. The more stickers hate groups post in the Burlington area, the larger the donation to local progressive organizations.

“We try to donate money directly to whatever group that was most targeted that month,” a Clean Up Crew member explained. Recently, due to a spate of transphobic flyering incidents, the BTV Clean Up Crew has been funneling donations to Outright Vermont, a local organization aimed at building an equitable and inclusive society for all LGBTQ+ young people. The Clean Up Crew has also donated to local organizations such as Migrant Justice and Black Lives Matter of Greater Burlington.

“It adds some levity to something that is so dire. It’s lemons to lemonade” said Rachel Frida Siegel, co-coordinator of the Old North End Mutual Aid (ONEMA), a local organization that was recently the recipient of BTV Clean Up Crew’s crowdfunded donations. “That money enabled us to make our community stronger by supporting people who needed resources that they couldn’t get otherwise.”

Part of the Clean Up Crew’s success in confronting hate in their community stems from their focus on preventing the amplification of extremist rhetoric and narratives. Group members do not alert the police or local media to the flyers and stickers but quietly remove them along with other types of trash.

For those interested in creating similar efforts in their community, the BTV Clean Up Crew recommends making a strong distinction between the bigotry espoused by hate groups and what might be considered differing politics. “Make it clear that what you’re trying to do is counter hate against neighbors” explained a Crew member. “These people are trying to attack your neighbors. These aren’t people who are trying to express their political beliefs.”

To support the BTV Clean Up Crew and learn more about their efforts to make “every neighbor feel loved and welcomed,” visit their Facebook page.

Community Coalition-Building: ‘Voices of Love and Unity’ for Afghan Refugees

By Caleb Kieffer

In the state of Washington, the American Muslim Empowerment Network at the Muslim Association of Puget Sound is leading a campaign to welcome refugees from Afghanistan.

“There's so much noise, and we need have our voices of love and unity to be louder than the haters that are always going to be there,” said Aneelah Afzali, executive director of MAPS-AMEN. “That's the approach we have to take.”

The United States has taken in around 75,000 Afghans since the chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021. As of Dec. 31, 2021, 52,000 have been resettled in communities across the U.S. Another 22,500 remain in temporary housing facilities awaiting completion of the process, according to the Department of Defense. Efforts to safely resettle Afghan refugees received bipartisan support from many lawmakers and the public, but the effort has not been without politicization. Anti-Muslim hate groups and some right-wing lawmakers used the opportunity to spread divisive rhetoric and bigotry.

Afzali and MAPS-AMEN sought to get ahead of the hate and send a welcoming message to arriving Afghan refugees. “We're likely going to see, and we've already seen, a spike in xenophobia and Islamophobia with a number of new Brown Muslims arriving in different parts of the state,” she said. “So, what we created are these welcome signs that just say we welcome our Afghan neighbors.” The signs feature a message flanked by colors of the U.S. and Afghanistan flags. She said the goal was to “distribute these welcome signs to really try to get ahead of the narrative and try to have public officials, leaders, and others step up and create that welcoming environment and try to maximize the kind of bi-partisan support [for refugees].”

In October 2021, Afzali joined Washington Gov. Jay Inslee, corporate partners and other community leaders at a press conference at the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport’s Welcome Center for Afghans to greet those arriving from Afghanistan and to speak out against recent violence against immigrant and Muslim communities. MAPS-AMEN is also partnering with the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services to provide support for refugees. This effort includes coordination between the government, resettlement agencies and community-based organizations, as well as the Afghan American community. Afzali said various working groups have been established to address housing, employment, health, legal services, donations, food and more.

Washington is one of the top 10 states taking in refugees, according to data from the U.S. State Department. The Southern Poverty Law Center tracked 50 anti-Muslim hate groups in 2021, including three in Washington. Anti-Muslim hate groups coalesced around anti-refugee sentiment in 2021. This rhetoric is likely to carry over into 2022 as the Biden administration announced plans last year to increase the United States’ refugee cap to 125,000. This is set to reverse Trump’s historically low cap of 18,000.

Afzali said she plans to continue the welcoming campaign through the next few months as more refugees arrive. “We're also helping make sure that families do not fall through the cracks. And it's so hard to do that because you have such an influx. Both the pace and the number of arrivals is significant.” She also stressed the importance of people showing up for the Afghan community. “That kind of welcoming message is not only important for the Afghan arrivals themselves to feel that support from the community, but again, also to help ensure that any of those voices that might otherwise want to thrive, those ugly voices of hate, that we nip them in the bud in advance. We cannot allow that hateful messaging to gain any kind of momentum.”

Liberation Through Education: Seeding Freedom in the Mississippi Delta

By Lydia Bates

Liberation education is premised on the idea “that you have the tools, knowledge, skills and resources to lead the life that you want to live,” explained Ki Harris, Executive Director of the Freedom Project Network.

Composed of three individual Freedom Projects in Sunflower County, Meridian, and Rosedale, Mississippi, each project supplements student education with programming geared toward agency and empowerment. The overarching Freedom Project Network was developed in 2016 to sustain each of the existing sites and grow the reach of the organization.

As Harris detailed, the organization’s work and goals are reflective of the traditions of the 1964 Freedom Summer Schools. Carrying the spirit of those schools forward, the Freedom Project Network seeks “to create a type of educational movement where students [are] taught to question, students [are] taught to interrogate, and students [are] taught to challenge oppressive systems in their community and the society at large.”

Having come to Mississippi with Teach for America in 2014, Harris knows the challenges that public-school teachers face in supporting students who are underserved and historically marginalized. “We’re taught [this is] an achievement gap” Harris explained, “but if we actually interrogate that further … that’s not true. It’s not an achievement gap, but an opportunity gap.”

As the Freedom Project Network seeks to bridge that gap with liberation education, students and staff are grounded in Love, Education, Action and Discipline – the LEAD Principles. Despite the instability of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, each Freedom Project has continued to provide LEAD-guided programming that goes well beyond the conventional bounds of after school extracurriculars.

In Love, Rosedale Freedom Project students established the Gender-Sexuality Alliance to support LGTBQ+ individuals in partnership with the LGBTQ Fund of Mississippi in 2021. Love also inspired the Freedom Project’s staff to adapt to changing public health conditions with “porch-visits” – meetings between staff and students on family home porches.

As the core of each Freedom Project’s mission, Education was the driving force behind reading, conversations and a speaker series centered on abolition at the Rosedale Freedom Project. Similarly, interactive education was the impetus for a summer trip to the Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, and the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute and 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham.

Throughout 2021, Freedom Project students harnessed Love and Education to guide their Action. Following research into food deserts – urban areas where fresh, affordable food is scarce – students in Meridian planted seven community gardens at senior living facilities, public housing complexes and churches. Meanwhile, Sunflower County Freedom Project students spent over 200 hours writing and editing their annual literary magazine, The Chapters of Life.

With Discipline, all Freedom Project students in Meridian maintained an above 3.0 GPA. Rosedale students visited four colleges and universities, and all senior Freedom Project students in Sunflower County were accepted to college.

According to Jalaya Liles Dunn, Director of SPLC’s Learning for Justice, “there’s a great deal of crossover between the LEAD Principles and the four domains of Learning for Justice’s Social Justice Standards — identity, diversity, justice and action — which LFJ hopes will contribute to more liberation in schools and communities as well.”

Similar to Learning for Justice, as the Freedom Project Network continues to plant the seeds of freedom through education, they are playing a crucial role “in shaping an inclusive, multiracial and multiethnic democracy,” Liles Dunn explained.

“An education for freedom provokes questions, ignites wonder and promotes critical thinking,” Liles Dunn said. “Ensuring that the next generation of leaders embraces identity and diversity and wields collective power and action to champion justice is a fundamental step to disrupting hate at its core.”

In the view of Harris and the Freedom Project Network, such questions and critical thinking form the educational foundation from which “blossoms all freedoms.”

To learn more about the Freedom Project Network and support them in their mission to seed freedom through education, visit their website.

Representation in Office: ‘We have to mobilize together’

By Jason Wilson

Before she became the first indigenous transgender woman elected to a state house in the United States, Kansas state Rep. Stephanie Byers spent 32 years teaching music to high school students.

During Byers’ own high school days at a public school in Oklahoma, an inspirational teacher opened her eyes to the fact that “music was available to everyone” regardless of their origins or income status.

This made her want to awaken others to the same possibilities.

“I wanted to use music to touch people's hearts, including in class,” Byers said. “I wanted to make it a joy.”

She taught first at a private school, and then a small rural school in Colorado.

“I understand the challenges faced by rural schools, and suburban schools, and inner-city schools,” she said. She now employs her firsthand experience in her service on the Kansas House Committee on Education.

Finally, she arrived at North Wichita High School, where, for over two decades, she was part of a community that offered inspiration, support and safety to its members.

“Inside that building there's a bubble of protection,” she said.

And that protection is extended not only to students.

In the years leading up to her retirement, Byers’s gender transition renewed her sense of the resilience that arises from tightly bonded school communities.

“I began living authentically in 2014 without knowing how my colleagues would respond,” she said. "But the faculty wrapped themselves around me and said, ‘We love you — how can we help you?”

This, and her intimate understanding of the challenges faced by LGBTQ students, led her to activism as anti-LGBTQ legislators around the country began pushing so-called “bathroom bills.”

“My activism on LGBTQ issues geared up after I began living authentically,” she said, and her skilled advocacy led to her achieving local and even national prominence as a transgender rights campaigner.

Friends and allies began encouraging her to run for office, and when the incumbent Democrat retired as representative of Kansas’s 86th District, Byers ran in the 2020 election, and won by 11 votes.

She has not forgotten her former colleagues and students, however. Indeed, she thinks the far right has chosen to highlight issues like so-called “critical race theory” precisely because they see schools as a place that promotes resilience in the communities they wish to scapegoat and target.

“That’s why we’re seeing the right-wing push on school boards,” she said, adding, "They see there’s a structure of safety there, and they want to tear that structure down.”

The outgrowths of the assault on schools are as apparent in Kansas as they are in the rest of the country, according to Byers.

“The screaming matches at school boards — that's happening in Kansas,” she said.

And in turn, this has affected teachers, who are also struggling to navigate educating during a pandemic.

“My friends who are still teaching are heartbroken,” she said. “They’re no longer seen as professionals by some of the parents of the students they teach.”

For now, in the legislature, that means her agenda is, first, to protect existing structures of resilience and safety.

“We’re still on the defensive,” she said of the Democrat “super-minority” that is contending with GOP efforts to enact bills that would, in one example, ban transgender girls from participating in girls’ sports.

On that specific issue, Byers said progressive activists around the country should “look past the shiny object,” and not be distracted by the anti-LGBTQ framing of the issue.

“It’s not about fairness in sports,” she said. “It’s about putting kids in closets.”

“We need to call it out for what it is: bullying,” Byers adds.

In other advice to those pushing back on hate, she said progress will not be piecemeal.

“We have got to unite together across this country,” Byers said. “We have got to realize that we have to mobilize together.”

Conclusion