In Louisiana, mass incarceration takes on a different face

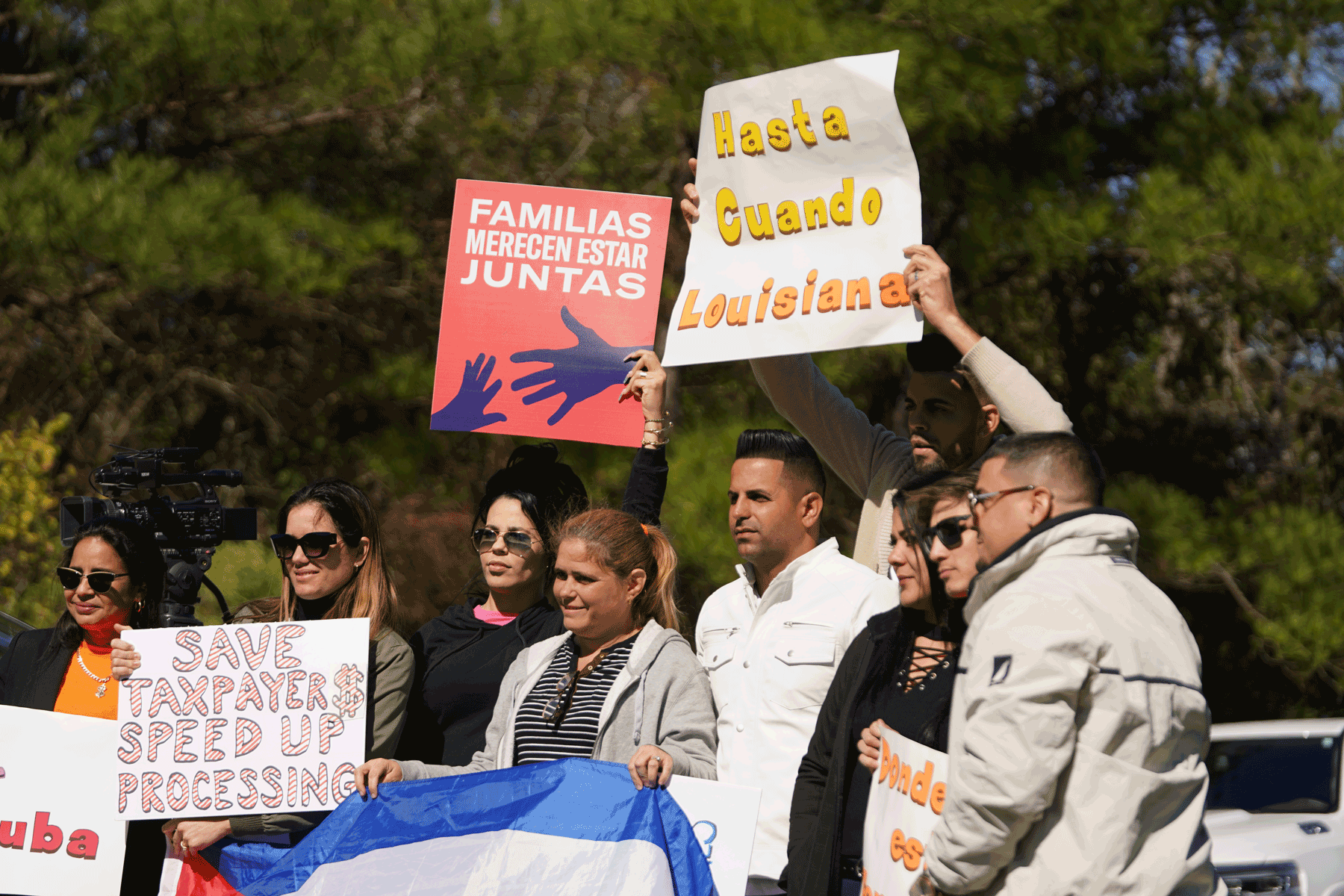

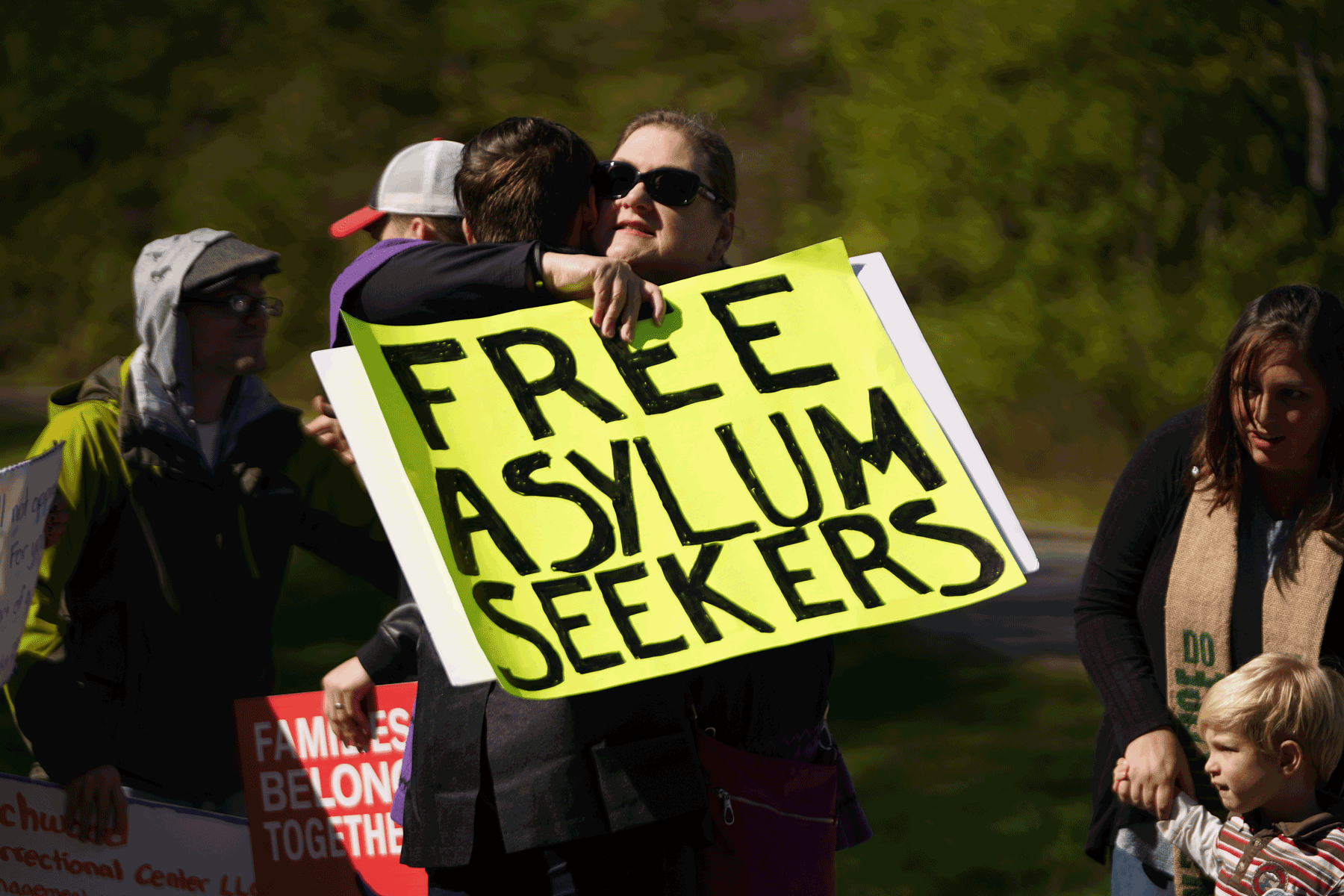

The protesters carried signs reading “Free asylum-seekers,” and “Richwood … your paychecks are covered in blood.”

They stood outside of Richwood Correctional Center near Monroe, Louisiana, where just a few weeks earlier, Cuban asylum-seeker Roylan Hernandez-Díaz, 43, became the second person to die in ICE custody since the new fiscal year began Oct. 1.

Some of the protesters, numbering about 30, had driven for hundreds of miles to protest Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s (ICE) practice of indefinitely locking up immigrants across the Southeast, often in shockingly inhumane conditions.

But, on Nov. 2, as they hoped to stand in solidarity with the men imprisoned at Richwood and to allow the men to hear their voices and shouts of support, police and prison staffers tried to prevent them from occupying a public space and getting within plain view of the immigrant prison.

“It begs the question: What are they trying to hide?” said Jared Davidson, an attorney with the SPLC. “This is all consistent with ICE’s attempt to cage immigrants in black boxes in among the most remote places in this country. It resembles a kind of rendition.”

The protest came as Louisiana is in the midst of transforming jails and prisons into detention centers for immigrants, many of whom arrived at the southern border to seek asylum, as is their legal right. In fact, the state – which until recently has been the incarceration capital of the country – is now becoming the epicenter of mass incarceration of immigrants.

Over the past 18 months, the state has more than quadrupled the number of migrants in detention, from 2,000 to nearly 9,000 at 11 facilities. Over the past year, eight jails, mostly in rural areas, have begun to accept immigrants.

It’s all about the money.

The detention centers are mostly tucked away in remote, rural communities that have long depended on incarceration for revenue and jobs. As state sentencing reforms are reducing the number of people in prisons and jails, empty beds are, in effect, being rented to ICE.

By converting former jails into prisons for immigrants, Louisiana is simply starting a new chapter in its dark past of imprisoning people of color by the masses.

“Louisiana has a long and painful history of locking up people of color in substandard and inhumane conditions,” said Lisa Graybill, SPLC deputy legal director. “While progress was made toward reversing incarceration through justice reinvestment, the decline in the state prison population has freed up beds for immigrant asylum-seekers. Real change will not come for Louisiana until our towns and our government stop relying on incarceration to drive our state and local economies. These prisons must close, not simply be repurposed.”

Profiting off brown and black people

As the national prison population exploded beginning in the early 1970s, Louisiana led the way. The state had the highest incarceration rate for decades and still ranks near the top among states. Due to recently passed legislation, however, the number of state prisoners – the majority of whom are African American – has slowly decreased.

Locking up and profiting off the bodies of black and brown people in Louisiana is a tradition as old as the state itself. The biggest change in Louisiana’s carceral system is who is making the money.

In 2018, Louisiana sheriffs were raking in $24 per day for each state inmate they housed and could garnish more than half the wages of inmates who held jobs with private companies outside of jail. And for every 100,000 people in Louisiana, 695 were state prisoners.

Locking up people in Louisiana is big business for private prison companies – like LaSalle Corrections, which owns Richwood and six of the eight newly converted jails – as well as for the local parishes where the jails are situated. Both the companies and the parishes continue to profiteer off incarcerating people of color.

With this move, sheriffs now anticipate reaping an average of $65 per day in payments from ICE for each immigrant detained. Detaining immigrants instead of state prisoners creates “an opportunity,” according to one Louisiana sheriff, and was described as “a blessing” by another.

Stuck in ‘hell’

When Hernandez-Díaz died, ICE ruled his death a suicide. His widow disagrees. She said that while her husband was frustrated when denied parole, he never expressed any suicidal ideations.

But along with the thousand other men detained at Richwood, Hernandez-Díaz had been subjected to horrific treatment since being locked up. The abuses the men suffer are now commonplace nationwide, but especially in Louisiana, where the tradition of housing people of color in horrific conditions runs deep.

Weeks before the protest, Mileydis Suarez, whose brother-in-law is detained at Richwood, told her that he was “abused all the time, psychologically.”

“The guards tell him he’s not going to get parole, that the undocumented don’t satisfy the requirements,” Suarez said. “The guards tell them they’re there to entertain them. All of the men are afraid, you can see it on their faces.”

Suarez also said that before the protest the men incarcerated at Richwood participated in a hunger strike to demand justice for Hernandez-Díaz. According to Suarez, the men wore sweatshirts with the words “Justicia para Roylan” written across their chests. When they sat down at the cafeteria table, they refused to eat.

But the peaceful protest turned violent within seconds, Suarez said.

“The guards threw men to the floor and handcuffed them,” Suarez said. “One guard smashed a man’s face into the wall. Another guard broke a man’s rib after he kneed him in the chest. The guards transported some men to solitary confinement. How can you punish them like that? It doesn’t make sense.”

The abuses at Richwood – and in immigrant prisons nationwide – have simply become routine.

In August, ICE sprayed over 100 immigrants with tear gas and left bruises on their torsos when they shot the men with rubber bullets. The agency also routinely blocks immigrants’ access to their families and attorneys, denies them their medical needs, and for little or no cause, places immigrants – some of whom suffer from severe mental illnesses – into solitary confinement.

Even more disturbing, a private autopsy revealed that a transgender woman had been physically beaten in ICE custody before she died from lack of proper medical care for HIV. In August, the SPLC and its legal partners filed a major, nationwide class action suit against ICE for failing to meet the medical, mental health and disability needs of the more than 50,000 people in its custody.

ICE has further employed a blanket policy of locking up people who have lawfully sought asylum in the Southeast.

The majority of these newly detained individuals have entered the United States legally and have sponsors ready to welcome them to the country. These immigrants have exercised their basic human right to freely seek asylum in the United States, yet they are held captive in conditions that closely mirror – or are worse than – those in prisons.

In May, the SPLC sued ICE over its illegal refusal to consider the men’s cases and grant them release to pursue their asylum claims from the safety of a sponsor’s home. A federal judge issued a preliminary injunction in September, ordering the New Orleans ICE Field Office to restore procedures for detained asylum-seekers to seek release through parole.

ICE, however, has since ignored and appealed that court order and is continuing to deny the men their release, leaving many feeling as if they are stuck in “hell.”

All the while, Louisiana sheriffs and private prison operators are raking in profits.

For Suarez – and for families and advocates like her – this money is tainted.

“I’ve been [in the United States] for a long time,” Suarez said. “They are using my money – our money – to detain my family. It’s filled with pain and stained in blood.”

Photos by Jannero Temple/Chowderjay Photography