Xenophobic Hatred Grows with Latino Population in Georgia

In Canton, Georgia, Guatemalan worker Domingo Lopez Vargas was brutally beaten by local teens looking for fun — a crime emblematic of racial tension and xenophobic violence on the rise in the region.

For the first time since the African slave trade closed down, the South experienced large-scale immigration by a "non-traditional" population in the 1990s.

Six of the seven states with the nation's fastest-growing Hispanic populations from 1990 to 2000 were in the South — including Georgia, where the number of legal Hispanic immigrants swelled by 300%. And demographers estimate that the total number of Hispanic immigrants, including those who are undocumented, is one and a half to two times that number.

A telling statistic: Hispanic babies now account for 12.6% of all births in Georgia, where the official percentage of Hispanics was 5.3% in 2000.

The growth is only accelerating. In the first few years of the new millennium, Georgia's Hispanic population grew faster than any other state's, and U.S. Census figures indicate that 102 Hispanics are moving there legally every day.

CANTON, Ga. -- On a frigid afternoon last February, Domingo Lopez Vargas decided to call it a day. A diminutive 54-year-old with bowl-cut hair and a gold tooth that gleams when he smiles, Lopez had left his dirt-poor Guatemalan farm village 15 years before, determined to earn some decent money for his wife and nine children.

After picking oranges in Tampa, Fla. — "too hot!" Lopez says — he'd joined a mid-1990s wave of immigrants heading for the piney hills and exploding exurbs of North Georgia. Lopez settled in Canton, a former mill village 35 miles north of Atlanta.

With the construction boom spreading ever northward from Atlanta, the area was fast becoming one of the most popular — and lucrative — U.S. destinations for immigrant workers.

Unlike many of his compadres, Lopez had legal status, which helped him find steady work hanging doors and windows. But last February, the work dried up and Lopez joined the more than 100,000 jornaleros — day laborers — who wait for landscaping and construction jobs on street corners and in front of 7-Elevens and other tiendas all across North Georgia.

Usually there are plenty of pickup trucks that swing by, offering $8 to $12 an hour for digging, planting, painting or hammering. But this day, nada. By late afternoon, Lopez had had enough of standing on Main Street waiting with others in the cold. He gave up and walked up the street to McFarland's, a grocery store in a beat-up shopping center.

"I got milk, shampoo and toothpaste," he recalls through an interpreter. "When I was leaving the store, this truck stopped right in front of me and said, 'Do you want to work?'" Lopez hasn't picked up much English in 15 years, but he knew what that meant. "I said, yes, how much? They said nine dollars an hour. I didn't ask what kind of job. I just wanted to work, so I said yes."

Until that afternoon, Lopez says, "Americans had always been very nice to me." Which might explain why he wasn't concerned that the guys in the green pickup — all four of them — looked awfully young to be contractors. Or why he didn't think twice about being picked up so close to sunset. "I took the offer because I know sometimes people don't stop working until 9 at night," he says.

The four young men, all students at Cherokee High School, drove Lopez to a remote spot strewn with trash. "They told me to pick up some plastic bags that were on the ground. I thought that was my job, to clean up the trash. But when I bent over to pick it up, I felt somebody hit me from behind with a piece of wood, on my back."

It was just the start of a 30-minute pummeling that left Lopez bruised and blooded from his thighs to his neck.

"I thought I was dying," he says. "I tried to stand up but I couldn't. I couldn't understand what they were saying." Finally, after he handed over all the cash in his wallet, $260, along with his Virgin Mary pendant, the teenagers sped away.

Hotbed of Hate

Lopez, it turned out, was only the latest victim in a series of robberies and assaults on Hispanic day laborers in Canton. The first report had come on Nov. 15, 2003, when 22-year-old immigrant Elias Tíu was jumped, robbed and beaten near the old mills in downtown Canton.

The most recent had been just one day before Lopez landed in the hospital, when 22-year-old Carlos Perez had been offered work by three teenagers — including two of those accused of assaulting Lopez.

The script was much the same: Perez had been driven to an abandoned house, punched with fists and clobbered with a metal pipe. He threw his wallet at the teenagers during the beating; they extracted his $300 in cash and tossed it back at him.

After reports of Lopez and Perez' assaults hit the news, it was just a matter of days before seven Cherokee High School students were under arrest. "At least one of them was going around school bragging about robbing and beating up Mexicans," says Canton's assistant police chief, Jeff Lance.

"They were looking for easy prey."

Police can't say how much "easy prey" the Cherokee students might have found between November and February. According to Lance, "a number" of day laborers reported similar robberies and assaults — highly unusual, he notes, because immigrants normally "don't want to deal with us."

Tíu was the only previous victim detectives were able to locate. "They tend to move from one house to another," Lance says, "so it's hard to find the victims."

Three solved cases were enough to send a jolt through Cherokee County. True, like most of North Georgia, Cherokee is about as conservative as it gets.

Conservative enough that not one single Democrat ran for election this year in the entire county. Conservative enough that a paper copy of the Ten Commandments was recently displayed on the second floor of Canton's Cherokee Justice Center.

Conservative enough that in 2002, when Cherokee High School Principal Bill Sebring banned t-shirts with rebel-flag imagery after black students complained, 150 white students showed up the next day defiantly clad in Dixie Outfitters shirt and caps with rebel flags and cheered on by adult protesters from the Sons of Confederate Veterans and other "heritage" groups.

But hate crimes? That's a different story.

"It just floored everybody," says Lance. "These good old boys from Cherokee High School doing this?" It's not clear whether these "good old boys" were involved in the rebel-flag protests, which forced the high school to close down for an entire day. (Principal Sebring declined to be interviewed for this story.)

But one of those charged with armed robbery, aggravated assault and abduction was 18-year-old Ben Cagle, an heir to one of the county's most powerful families; his grandparents founded the Cherokee Republican Party, which so dominates local politics that not a single Democrat ran for office this year in the county. Cagle was president of Cherokee High's agricultural club.

Eighteen-year-old Devin Wheeling, the only teenager charged in all three incidents, was a JROTC cadet. Another of the alleged perpetrators was an Explorer Scout planning to become a firefighter. They'd known each other since middle school, played Dizzy Dean baseball and gone to church together.

Nobody was more floored than Lopez, of course. His injuries kept him out of work for four months, and left him with more than $4,500 in medical bills. Sometimes he still puzzles over his attackers' motives.

"They were young," he speculates, "and maybe they didn't have enough education. Or maybe their families are murderers who taught them to kill people, and that is what they have learned."

Or maybe they grew up in America's latest hotbed of anti-immigrant hate.

Hispanic immigrants started arriving here in big numbers in the early 1990s, many helping to build venues for the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta. Others headed north for Dalton's carpet factories and Gainesville's poultry plants. Some took to the street corners and started working day labor in Atlanta's booming suburbs, where cheap landscaping and construction help was — and is — in constant demand.

Coming to America

Day laborers are the most visible — and vulnerable — faces of a phenomenon that is rapidly transforming North Georgia into a diverse, multilingual place that one anti-immigration activist calls "Georgiafornia."

The official census numbers say Georgia's Hispanic population climbed 300% in the 1990s, adding up to 435,000 newcomers; demographers say the real number, counting illegal immigrants, is probably twice as high, and climbing. And like California before it, the state has become an epicenter for radical anti-immigration activism.

Immigration into other Southeastern states has generated low-level controversy and occasional outbursts of anti-immigrant rhetoric. In Georgia, many of the allegations are familiar: higher crime rates, littered streets, gang activity, millions spent on health care and education for "illegals."

But the backlash here has been unusually fierce. At first, the resistance was scattered, mostly taking the form of police crackdowns — arresting day laborers for loitering — and old-fashioned racial rhetoric.

In the formerly homogenous town of Chamblee, just north of Atlanta, white residents began complaining as early as 1992 about the "terrible, filthy people" standing on their street corners. At a town council meeting, one official infamously suggested that residents set bear traps in their yards to keep the Hispanics at bay. Another councilman wondered aloud whether Chamblee whites should form a vigilante group to scare off the immigrants.

Familiarity seems only to have bred contempt. Nine years after the infamous council meeting in Chamblee, Police Commander Wayne Kennedy, just down the road in Marietta, told a reporter his department had cracked down on day laborers because of residents' complaints about trash and urine in their yards.

"I guess it's a cultural thing," Kennedy said. "Probably in Mexico urinating on the sidewalk is perfectly normal."

The culture clash was predictable enough, says Remedios Gomez Arnau, Atlanta's consul general of Mexico.

"We're talking about a very new migration wave into Georgia," she says. "These are mostly people who have not been involved in traditional migrant work in the past. They're from the poorest, most rural and impoverished places in Mexico and Guatemala. And they are coming to a place where people are not familiar with migrant laborers, or with Hispanics.

A place where, in the words of Republican state Rep. Chip Rogers, "Everybody had a Southern accent when I was growing up. We were part of the Old South, for better or worse. We were all the same."

During the days of Jim Crow, some North Georgia towns enforced that sameness with a heavy hand. Signs warning black people to be out of town by sunset, some erected by local officials and others by Ku Klux Klan klaverns and White Citizens Councils, were familiar fixtures in the hills stretching north from Atlanta to the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Those signs are long gone, but the mindset lingers. "Prejudice is an old, old habit to break in Georgia," says Pilar Verdes, local news editor for Atlanta's Mundo Hispánico newspaper.

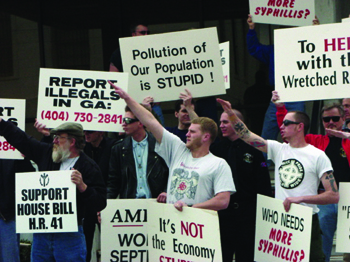

In every part of the U.S. where large numbers of Hispanic immigrants have moved, anti-immigration groups have sprung up in protest. But the backlash in Georgia has been fueled not only by these "mainstream" groups, but also by hardcore neo-Nazis, Southern "heritage" activists and white-supremacist hate groups — all of them saying strikingly similar things about the "Mexican invasion."

To immigrant-rights activists like Tisha Tillman, Southeast regional director for the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF), the hate crimes in Canton show just how deep a chord these groups' messages are striking.

"The kids who committed these crimes had grown up listening to people saying that Hispanic people were lower forms of life," she says. "We know what kind of effect that rhetoric has. Day laborers are the canaries in the coal mines for immigrant communities — they're out there, exposed, as visible symbols of the community. When they're being targeted, you know there's something seriously wrong."

Stage Right: Enter the Klan

One of the first signs that Georgians' anti-Hispanic prejudice was hardening into hate came in 1998, courtesy of the Klan. In Gainesville, the self-proclaimed "poultry capital of the world," the American Knights of the KKK held a Halloween rally on the steps of the Hall County Courthouse, followed by a cross-burning in nearby Winder. As in much of North Georgia, the sight of angry men in white hoods was old news in Hall County. But the message was new.

"They screamed their disapproval of the recent Hispanic influx into the Gainesville community," wrote Kathleen Cole, who photographed the rally for Flagpole, an alternative paper based in Athens. Blacks, Jews, Catholics, gay men and lesbians — the Klan's traditional targets seemed forgotten.

Now, Cole said, "preaching against illegal immigrants" was the topic of the day.

After a turbulent backlash against the African-American civil rights movement of the 1950s and '60s, Gainesville's white and black communities had settled into an uneasy, largely segregated coexistence before their new Hispanic neighbors began to arrive. But remnants of the old white resistance had lingered all along.

Like everywhere else, the Klan has shrunk in size over the years. But the white-supremacist Council of Conservative Citizens — successor to the old White Citizens Councils — has a thriving chapter in Hall County, spreading the CCC's message that "the United States is not only ceasing to be a majority white nation but is also ceasing to be a nation that is culturally part of Western civilization."

Gainesville is also home to the Georgia Heritage Coalition, which — when it's not defending the Confederate battle flag — spreads the word that "Immigration is out of control — and you are being lied to."

And in 2001, the nation's largest neo-Nazi organization, the National Alliance, announced its presence in Hall County with a rally organized to protest a proposed work center for local day laborers.

Fearing violence, immigrants and their allies steered clear of the rally, where between 30 and 40 National Alliance members carried signs with messages like "The U.S. is the world's septic tank" and "Full!"

But Pilar Verdes of Mundo Hispánico decided to see what the neo-Nazis had to say. She got an earful — especially after she attended a private rally held afterward at the Dahlonega home of National Alliance organizer Chester Doles, a former Klan grand dragon himself.

"This has nothing to do with hate," Doles told Verdes, who immigrated from Venezuela in 1989. "Hispanics are going to take America. We are going to be the minority."

Thomas Chittum, ex-mercenary in Croatia and Rhodesia and author of an anti-immigration tome called Civil War II: the Coming Breakup of America, picked up on Doles' theme. "The Southeast is going to be occupied by Mexicans, and this is going to create the beginning of a second Civil War here," he said.

"This is going to be an ethnic war."

"I was having an out-of-body experience," Verdes says. "I kept having to pinch myself. I never thought they would be so stupid to say those things. I was not hiding my tape recorder. They're very exhibitionist. And scary."

"This nation was founded by white men," Steven Barry, editor of the neo-Nazi Resister magazine and then an Alliance principal, told Verdes. "We don't need colors." Barry went on to talk about his models for resisting the Hispanic influx.

"Three of my heroes are Pinochet, Franco and the junta militar" — the notorious military board of Argentina. "Pinochet should come to the U.S. and solve our problems," Barry told Verdes. "It's good to torture people who deserve it."

Verdes was finally chased off — as fast as she could run — by a neo-Nazi who didn't like her questions. But Doles' National Alliance chapter, one of the nation's first organized around immigration issues, was just getting warmed up.

Three months after the rally, flyers began showing up on windshields in Metro Atlanta proclaiming, "Missing: A Future for White Children." Doles told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution his group would "blanket" the state to "raise awareness of the immigration issue."

A year later, the National Alliance held another rally in Gainesville to protest what it called "the brown tide ... turning Hall County into just another Third World cesspool." Despite a drizzling rain, the neo-Nazis drew twice as many supporters as they had in 2001.

Doles led a march around the blooming crepe myrtles of Gainesville's town square, bellowing: "What do we want?"

"Mexicans out!" came the answer.

"When do we want it?"

"Now!"

The neo-Nazis' momentum was slowed last year when Doles landed in prison on firearms charges. But to Greg Bautista, who runs El Puente Community Action in Gainesville, their fiery rhetoric had already done its work. "Those rallies were when people really started to profess their hate openly," he says. "They created a public space for that kind of message, that kind of talk."

Organizing the Resistance

Nobody has talked more about the perils of immigration in Georgia than D.A. King. An ex-Marine from Marietta, a white-flight suburb just outside of Atlanta, King regularly contributes dispatches from "Georgiafornia" to the anti-immigration Web hate site, VDARE.com.

In the late 1990s, he worked with the Georgia Coalition for Immigration Reduction. Allied with the nation's largest anti-immigration group, the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), the coalition has organized protests and filled its Web site with facts and figures about the impact of immigration on Georgia taxpayers.

Last fall, King decided that wasn't cutting it. He took early retirement from his insurance agency to launch a far more ambitious effort: American Resistance, a national "coalition of immigration crime fighters."

"Immigration reform is a dead issue to me," says King. "I don't want to talk about cutting the numbers of legal immigrants. I want to put a stop to the crime of illegal immigration."

Three days after he announced American Resistance on VDARE and www.michnews.com, King says he'd already gotten 630 E-mails from folks interested in paying the $39 membership fee.

Almost a year later, he'll only say that he has "fewer than 5,000" paying members nationally and "fewer than 1,000 in Georgia." But King vows that he "won't stop until I have 1 million members" — hopefully in time for the 2006 elections — and offices with full-time staff in all 50 states.

"The NRA is an excellent business model," he says, referring to the powerful National Rifle Association, and his goal is to exert the same kind of influence on American politics.

Other than that, King is a bit vague about the kind of "resistance" he aims to spread. He urges members to report illegal immigrants to Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (BICE) offices when they see them — something King did in September 2003, after spotting a photograph of three illegal immigrants on the front page of the Marietta newspaper. King took their names and addresses to the bice agents in Atlanta. Two months later, he was furious to discover two of them still free on the streets of Marietta, walking "symbols of the anarchy that is destroying the American nation." His conclusion: "Adios, law — hola, anarchy."

This September, when a rally supporting driver's licenses for immigrants took place at the state capitol, King encouraged BICE agents to arrest those carrying signs, explaining to a local paper, "If I hold up a sign that says I want to rob banks legally, I think it's safe to say I'm a bank robber."

In the absence of la migra, King organizes counter-protests. About 50 American Resisters showed up to protest the driver's license rally. They carried signs like "Gringos for America" and chanted such slogans as "You Cannot Have My Country!" and "Enforce the Law!" — despite often being drowned out by what King described as "a crowd of 800-1500 screaming illegal aliens and their enablers."

Those "enablers" — groups like MALDEF and the National Council of La Raza — are the real bigots in this debate, King insists. "The racist forces that would take our country have made their intentions clear," he declares on the American Resistance Web site.

"The days of illegal aliens threatening and intimidating American citizens who show the courage to protest their national dispossession must, and will, end."

'I Want You to Suffer'

D.A. King's white-victimhood theme was memorably expressed after he protested the Freedom Ride for Immigrant Workers when it rolled through the Atlanta suburb of Doraville in the fall of 2003.

Seeing upwards of 2,000 Hispanics marching through the formerly homogenous little town, King wrote on VDARE, "I got the sense that I had left the country of my birth and been transported to some Mexican village, completely taken over by an angry, barely restrained mob. ... My first act on a safe return home was to take a shower."

Asked what percentage of Georgia citizens agree with his sentiments, King doesn't hesitate. "Probably 95," he says.

Certainly, he has some powerful political allies. Three North Georgia congressmen, Republicans Charlie Norwood, Nathan Deal and Phil Gingrey, belong to the controversial Congressional Immigration Reform Caucus, led by anti-immigration rabble-rouser Tom Tancredo, a Colorado congressman.

In the Georgia General Assembly, State Rep. Chip Rogers of Cherokee County has sponsored three anti-immigration bills, one of which would cut off all state services to illegal immigrants. "I don't think these folks are coming to America so they can make use of our social services, our schools and hospitals," Rogers says.

"They're coming for work. But we can't fail to recognize what it's doing to our health-care system, our prisons and our schools. One study showed that the state of Georgia spent $260 million to educate illegal immigrants last year."

Rogers acknowledges that "some people are beginning to target people for hatred," but he lays the blame largely on the immigrants themselves. "I truly believe that if it weren't for the high levels of illegal immigration, we wouldn't have the targeting, the prejudice, even if there were still high numbers of Hispanic people in Georgia.

"With so many people illegal, people tend to assume they are all illegal, and it becomes, 'Yeah, I couldn't get into the emergency room because of all those illegals there.' It feeds the prejudice."

Rogers admires King's efforts with American Resistance, which he believes produces "great research." But he keeps a distance, he says, because, "some of his associates are on the radical side."

Even though they're usually on opposite ends of legislative issues, Rogers wouldn't get any argument from Democratic state Sen. Sam Zamarripa about that.

"If American Resistance was really genuine about immigration reduction, they'd be protesting the big employers in America," says Zamarripa, one of the state's most outspoken proponents of immigrants' rights.

"The big companies are the ones who want cheap labor, and real enforcement of immigration laws would have to start with workplace enforcement. But they won't call for that, because that's not what their issue is. Their issue is ethnic. Their issue is that they don't want America to have any more color. They represent the worst of this anti-immigration theme that outsiders destroy America."

Zamarripa has paid a price for talking back to anti-immigration activists, and for sponsoring bills like the drivers' license proposal in the state Senate. "I'm watched and I'm tracked," says Zamarripa, who indeed is the subject of a "Zamarripa Watch" on American Border Patrol, an anti-immigrant hate site that often runs King's dispatches from Georgia.

American Border Patrol has called Zamarripa a "Mexican agent" and "Reconquista" (meaning that he's a part of the Mexican government's supposed plot to "reconquer" parts of the U.S.). Every time he's featured on VDARE or American Border Patrol, Zamarripa says, he starts getting E-mail messages — "love letters," he calls them — from anti-immigration zealots.

On the heels of King's "Zamarripa Watch" story about the drivers-license issue this summer, the senator received an e-mail message that particularly disturbed him. "My hope is that when the next terrorist act takes place in the United States ... your children will be the recipients of that terror. Yes, your children. I want you to suffer."

"These messages are directly correlated to the attention I get from American Resistance," says Zamarripa. "I think these people are operating just barely north of vigilante. They might not be traditional 'hate' groups, like the Klan, but that's part of the appeal. They provide a safe, so-called respectable haven for hatred and bigotry."

Official Bigotry

In the charged atmosphere of North Georgia, bigotry tends to bubble up in surprising settings — like city council chambers. This September, 12 years after a Chamblee councilman recommended catching immigrants in bear traps, a verbal melee broke out at what was supposed to be a routine city council meeting in neighboring Doraville.

Once an overwhelmingly white suburb of 10,000, celebrated in pop song by the Atlanta Rhythm Section as "a touch of country in the city," Doraville is now 43% Hispanic officially — and perhaps 60% unofficially.

The city has seen some "white flight" in response, but not by its elected officials: Until this January, Doraville's mayor and six council members were all white men between the ages of 60 and 73 who'd been in office for more than two decades. The council now has a Hispanic member and a woman. But the old regime made itself heard on Sept. 20.

Doraville had decided to charge sponsors of an Oct. 12 "Festival de la Raza" (raza means "race") march $2,000 for police security — an unprecedented fee with no basis in local law.

When members of the march's sponsoring group, the Coordinating Council of Latino Community Leaders of Atlanta, decided to attend the Sept. 20 council meeting to protest, state Sen. Vincent Fort of Atlanta went with them.

Fort, a history professor at Morris Brown College who represents a predominantly African-American district in the city, believed that charging for security "was a violation of free speech. It was clear to me that they were being treated differently because of who they are."

As a civil-rights activist and a student of civil-rights history, Fort felt compelled to stand with the protesters. In fact, he was the first to speak. But almost as soon as he began, Lamar Lang, a former Doraville mayor who now sits on the council, interrupted to question Fort's right to address the council.

"Being a senator doesn't cut any ice with me," Lang said. "I'm going to call a spade a spade."

After a brief but heated exchange, Fort resumed reading his statement in support of the marchers. And then Lang got really cranked up. "Latinos are freeloaders," he declared. "The city doesn't have to pay for charges incurred by the undocumented."

A couple of weeks later, Lang issued an apology of sorts, saying, "Maybe I shouldn't have made that statement." After some negotiations with the Doraville police chief, the Festival de la Raza went off without a hitch. Of course, D.A. King and a band of American Resistance members were part of the crowd.

In the wake of the city council meeting, Fort couldn't help being struck by the parallels between the backlash against black civil rights and the current anti-immigration movement.

"Ultimately, Lang was saying what many people in Doraville — and this whole area — believe. As their numbers increase, you're going to see more and more resentment against Latinos in Georgia, not less.

"And especially as they start to assert themselves and defend their rights, it won't be pleasant. We know that from the civil-rights movement.

"Take the hate crimes in Canton. People usually don't report those kinds of incidents, because many of them are undocumented and fear the police. If one or two are reported, you know there are a lot more of those crimes happening. And we won't see an end of them any time soon."

Life and Death in Georgia

While Georgia's immigration debate heats to a boiling point, Domingo Lopez Vargas waits for justice — justice, and a ticket home. Having sworn off day labor, he works night shifts now, cutting up chickens at the nearby Tyson plant, wincing through the pain that shoots up his right arm when he lowers the boom on a bird.

But it's only temporary, he says. "I called my wife and told her what happened. She told me to move back to Guatemala. I wanted to, but I didn't have enough money to go back and the police officers told me not to go out of the country because they will still need me to work on the case. After the case is finished, I want to go back to my family."

It could take a while. At press time, no trial date had been set for Lopez' assailants. The delay is not particularly surprising, since Cherokee County's district attorney and both its Superior Court judges removed themselves from the case, citing their ties to defendant Ben Cagle's prominent Republican family. The prosecution had to be shifted to neighboring Cobb County, home base of American Resistance.

Until Oct. 25, when Georgia's hate-crime law was declared unconstitutional because of vague wording, activists were pressing the Cobb County district attorney to bring hate crime charges against Lopez' assailants — and those of Carlos Perez and Elias Tíu.

"These victims were chosen, clearly, because they were Latino day laborers," says MALDEF's Tisha Tillman. "And if you're going to say that robbery was the motive, why were these men beaten with fists and sticks and pipes?"

Because so few atrocities committed against Hispanics are ever reported — much less brought to trial — Angela Arboleda, civil-rights analyst for the National Council of La Raza, says justice is especially important in this case, hate crimes or no hate crimes.

"The message sent by these assaults is already bad enough," she says. "If you wake up at 5 a.m. and want to work hard in Georgia, you're putting your life at risk."

Every weekday morning, just down the hill from the old mill house where Lopez lives, scores of laborers still gather to take that risk.

On a misty morning in late September, a couple of dozen have assembled at MUST Ministries, a two-story brick storefront converted into one of Georgia's few job centers for day laborers. MUST provides a measure of safety, taking contractors' names and license-plate numbers in case there's trouble.

But many contractors prefer to stop up the street, where dozens more men wait in front of Tienda Guatemalteca and La Luna Panadería, a bakery — and where no ID is required.

"Everyone knows it's dangerous," says Manolo, an ebullient 22-year-old from Chiapas, in southern Mexico, who's volunteering at MUST on a late September morning.

"American men — they don't like to pay. That's usually the trouble. But some people have been robbed and beaten — right up there." He points up the street toward one of the unofficial work sites, where dozens of jornaleros have crowded around a contractor's truck, clamoring for work.

A few blocks up the street at La Luna Panadería, Antonio (who doesn't want to give his last name) believes things have gotten a little better since he arrived in Canton four years ago.

Back then, "Americans would throw things out their cars at me when I would walk down this street to lunch." On one memorable occasion, as he walked through the local park with friends, he says a group of black and white men drove by and opened fire on them with pellet guns.

That hasn't happened in a while, Antonio says. But there was that day last year when he came to work to find a dead man out front on the sidewalk. "He had bruises all over like he was beaten," Antonio says.

The police came, the body was taken away, and "The Latino community still has no idea what happened." Nor do Canton police. But since the Cherokee High School students were rounded up, says Assistant Police Chief Jeff Lance, no more bruised Hispanic bodies have been reported in Canton.

"It's been real quiet," Lance says. "Knock on wood."