The Year in Hate & Extremism, 2010

Led by the antigovernment ‘Patriot’ movement, the American radical right is continuing to expand rapidly

Editor's note: Since the article below was published, authorities have changed their view of an incident in Dearborn, Mich., that is mentioned. Initially, it was believed that the Michigan suspect was planning an attack based on hatred of Muslims. In fact, it turns out that Roger Stockham is an American convert to Sunni Islam, and reportedly was angry at the mosque in question because it was Shi'ite.

For the second year in a row, the radical right in America expanded explosively in 2010, driven by resentment over the changing racial demographics of the country, frustration over the government’s handling of the economy, and the mainstreaming of conspiracy theories and other demonizing propaganda aimed at various minorities. For many on the radical right, anger is focusing on President Obama, who is seen as embodying everything that’s wrong with the country.

Hate groups topped 1,000 for the first time since the Southern Poverty Law Center began counting such groups in the 1980s. Anti-immigrant vigilante groups, despite having some of the political wind taken out of their sails by the adoption of hard-line anti-immigration laws around the country, continued to rise slowly. But by far the most dramatic growth came in the antigovernment “Patriot” movement — conspiracy-minded organizations that see the federal government as their primary enemy — which gained more than 300 new groups, a jump of over 60%.

Taken together, these three strands of the radical right — the hatemongers, the nativists and the antigovernment zealots — increased from 1,753 groups in 2009 to 2,145 in 2010, a 22% rise. That followed a 2008-2009 increase of 40%.

What may be most remarkable is that this growth of right-wing extremism came even as politicians around the country, blown by gusts from the Tea Parties and other conservative formations, tacked hard to the right, co-opting many of the issues important to extremists. Last April, for instance, Arizona Gov. Jan Brewer signed S.B. 1070, the harshest anti-immigrant law in memory, setting off a tsunami of proposals for similar laws across the country. Continuing growth of the radical right could be curtailed as a result of this shift, especially since Republicans, many of them highly conservative, recaptured the U.S. House last fall.

But despite those historic Republican gains, the early signs suggest that even as the more mainstream political right strengthens, the radical right has remained highly energized. In an 11-day period this January, a neo-Nazi was arrested headed for the Arizona border with a dozen homemade grenades; a terrorist bomb attack on a Martin Luther King Jr. Day parade in Spokane, Wash., was averted after police dismantled a sophisticated anti-personnel weapon; and a man who officials said had a long history of antigovernment activities was arrested outside a packed mosque in Dearborn, Mich., and charged with possessing explosives with unlawful intent. That’s in addition, the same month, to the shooting of U.S. Rep. Gabrielle Giffords in Arizona, an attack that left six dead and may have had a political dimension.

It’s also clear that other kinds of radical activity are on the rise. Since the murder last May 20 of two West Memphis, Ark., police officers by two members of the so-called “sovereign citizens” movement, police from around the country have contacted the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) to report what one detective in Kentucky described as a “dramatic increase” in sovereign activity. Sovereign citizens, who, like militias, are part of the larger Patriot movement, believe that the federal government has no right to tax or regulate them and, as a result, often come into conflict with police and tax authorities. Another sign of their increased activity came early this year, when the Treasury Department, in a report assessing what the IRS faces in 2011, said its biggest challenge will be the “attacks and threats against IRS employees and facilities [that] have risen steadily in recent years.”

Extremist ideas have not been limited to the radical right; already this year, state legislators have offered up a raft of proposals influenced by such ideas. In Arizona, the author of the S.B. 1070 law — a man who just became Senate president on the basis of his harshly nativist rhetoric — proposed a law this January that would allow his state to refuse to obey any federal law or regulation it cared to. In Virginia, a state legislator wants to pass a law aimed at creating an alternative currency “in the event of the destruction of the Federal Reserve System’s currency” — a longstanding fear of right-wing extremists. And in Montana, a state senator is working to pass a statute called the “Sheriffs First Act” that would require federal law enforcement to ask local sheriffs’ permission to act in their counties or face jail. All three laws are almost certainly unconstitutional, legal experts say, and they all originate in ideas that first came from ideologues of the radical right.

There also are new attempts by nativist forces to roll back birthright citizenship, which makes all children born in the U.S. citizens. Such laws have been introduced this year in Congress, and a coalition of state legislators is promising to do the same in their states. And then there’s Oklahoma, where 70% of voters last November approved a measure to forbid judges to consider Islamic law in the state’s courtrooms — a completely groundless fear, but one pushed nonetheless by Islamophobes. Since then, lawmakers have promised to pass similar laws in Arizona, Florida, Louisiana, South Carolina, Tennessee and Utah.

After the Giffords assassination attempt, a kind of national dialogue began about the political vitriol that increasingly passes for “mainstream” political debate. But it didn’t seem to get very far. Four days after the shooting, a campaign called the Civility Project — a two-year effort led by an evangelical conservative tied to top Republicans — said it was shutting down because of a lack of interest and furious opposition. “The worst E-mails I received about the Civility Project were from conservatives with just unbelievable language about communists and some words I wouldn’t use in this phone call,” director Mark DeMoss told The New York Times. “This political divide has become so sharp that everything is black and white, and too many conservatives can see no redeeming value in any” opponent.

A Washington Post/ABC News poll this January captured the atmosphere well. It found that 82% of Americans saw their country’s political discourse as “negative.” Even more remarkably, the poll determined that 49% thought that negative tone could or already had encouraged political violence.

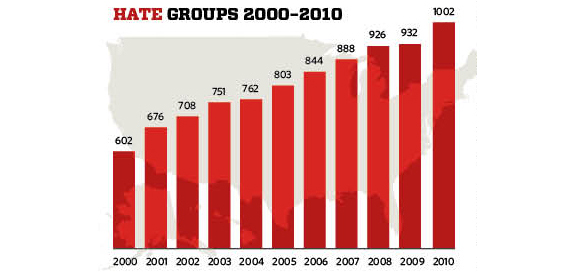

Last year’s rise in hate groups was the latest in a trend stretching all the way back to the year 2000, when the SPLC counted 602 such groups. Since then, they have risen steadily, mainly on the basis of exploiting the issue of undocumented immigration from Mexico and Central America. Last year, the number of hate groups rose to 1,002 from 932, a 7.5% increase over the previous year and a 66% rise since 2000.

At the same time, what the SPLC defines as “nativist extremist” groups — organizations that go beyond mere advocacy of restrictive immigration policy to actually confront or harass suspected immigrants or their employers — rose slightly, despite the fact that most of their key issues had been taken up by mainstream politicians. There were 319 such groups in 2010, up 3% from 309 in 2009.

But like the year before, it was the antigovernment Patriot groups that grew most dramatically, at least partly on the basis of furious rhetoric from the right aimed at the nation’s first black president — a man who has come to represent to at least some Americans ongoing changes in the racial makeup of the country. The Patriot groups, which had risen and fallen once before during the militia movement of the 1990s, first came roaring back in 2009, when they rose 244% to 512 from 149 a year earlier. In 2010, they rose again sharply, adding 312 new groups to reach 824, a 61% increase. The highest prior count of Patriot groups came in 1996, when the SPLC found 858 (see also chart, above).

It’s hard to predict where this volatile situation will lead. Conservatives last November made great gains and some of them are championing a surprising number of the issues pushed by the radical right — a fact that could help deflate some of the even more extreme political forces. But those GOP electoral advances also left the Congress divided and increasingly lined up against the Democratic president, which is likely to paralyze the country on such key issues as immigration reform.

What seems certain is that President Obama will continue to serve as a lightning rod for many on the political right, a man who represents both the federal government and the fact that the racial make-up of the United States is changing, something that upsets a significant number of white Americans. And that suggests that the polarized politics of this country could get worse before they get better.