Miller's Crossing

After years of propagandizing, neo-Nazi Frazier Glenn Miller is accused of a triple murder. The violence was a long time coming.

MARIONVILLE, Mo. — The troubled Miller boys are buried side-by-side, a few yards from the two-lane blacktop that cuts through the middle of the cemetery on the edge of this small country town. Each brother met a tragic end at an early age. One perished in a ball of

flames, the other in a shootout with the law. Yet, even in death, their father, Frazier Glenn Miller, the notorious neo-Nazi and now triple-murder suspect in last spring’s Jewish community center terrorist attacks in Kansas, will not allow his sons to rest in peace. Engraved on their matching gray headstones is “88” — the numerical symbol for “Heil Hitler.”

Miller’s right-wing politics, prayers and delusions are all over the polished granite stones, which proclaim his sons to have been young “Saxon Braveheart” rebels who “Ride Now Forever” with the “Valkyrie Angels in the Heavens.”

Mike, the youngest and wildest Miller brother, the one who tried hardest to please his daddy, was the first to take the ride. He was killed in 1998 in a fiery car crash. He was just 19 and not long out of prison for committing a racially motivated arson. In the middle of a winter night, when he was 17, Mike had lobbed a Molotov cocktail into the back of a trailer home, filled with sleeping people, including, most disgustingly, according to his father’s twisted life’s lessons, a young black man and his white girlfriend.

Jesse, a year older than Mike and in possession of a calmer spirit, died a decade later in what the Lawrence County Sheriff describes as an Old West shootout. Jesse was driving with his mother to put flowers on his brother’s grave, got into a car accident, and inexplicably shot to death a man who stopped to help. He then went marching towards town, brandishing a shotgun. When a Marionville police officer arrived, Jesse shot him, too. The officer survived and returned fire, killing Jesse, who died along the side of the road.

“I think a lot of it had to do with their upbringing,” the sheriff, Brad DeLay, told the Intelligence Report. “To me they kind of appeared to be Frazier’s muscle men. If something were to happen, while we never could directly link it to him, you just had that feeling they were probably doing something that daddy wanted them to do or had talked about.”

Running his mouth and delivering hand-written letters to the Aurora Advertiser about the Jewsmedia, the invasion of America by brown-skinned immigrants and the oppression of the white man by big government is all that Miller, a once prominent Klan leader, seemed to ever do. His words were often vile, riled folks up and caused Kim McCully-Mobley, the editor, “constant headaches and angst.” But otherwise, McCully-Mobley said, “everyone thought he was harmless. He just wanted some attention.” When Miller purchased his first computer in 2004, McCully-Mobley and her colleagues were relieved and wished they had pitched in and bought him one earlier. He largely switched his ranting to the Internet and became, according to his white nationalist critics, just another all talk, no action “keyboard Nazi.”

Sheriff DeLay puts it a little differently. He has known Miller, who also goes by Frazier Glenn Cross and Frazier Glenn Mays, for about 20 years. “Other than Frazier offering lip service,” the sheriff said, “we’ve never actually known him to do anything hands on himself.” So, the sheriff was flat-out flabbergasted when the sickly, 73-year-old Miller was arrested for allegedly shooting to death three unarmed people, including a 14-year-old boy, on April 13, the day before Passover, at a Jewish community center and a nearby Jewish assisted living facility in a suburb of Kansas City, about 190 miles from his home here in Southern Missouri farm country.

But unlike his doomed sons, when Miller was confronted by police that April afternoon in Overland Park, Kan., he did not try to go out in a blaze of Saxon Braveheart glory. Instead, he put down his shotgun and surrendered. Then, safely handcuffed in the back of a squad car, he did a little more talking.

“Heil Hitler,” he shouted.

Home With the Millers

Miller was whisked away that bloody Sunday and charged with killing William Lewis Corporon, a 69-year-old physician, and his grandson, Reat Griffin Underwood, 14, in the parking lot of the Jewish Community Center of Greater Kansas City. Reat, along with hundreds of other teenage hopefuls, was at the center to audition for a singing contest. Miller was also charged with the murder of Terri LaManno, 53, as she made her weekly visit to her mother at Village Shalom, an assisted living facility a short distance from the community center.

“Frazier was more racist against Jews than he was black people,” said Connie, Mike Miller’s former girlfriend, who lived with the family for more than a year when she was a teenager. “We weren’t allowed to have cable in the house, so we weren’t exposed to the things Jews wanted us to believe. He said they ran the media and they were the reason for the white downfall.”

None of the people Miller was charged with killing that day were Jewish. But part of Miller’s grandson’s family, on his mother’s side, is from Israel, a fact kept hidden from Miller for years out of fear. Mike Miller and Connie, who asked that her last name not be used, had a son. When the elder Miller learned that she was pregnant with his grandchild, the future of the Aryan nation, he insisted Connie move in with his family. She was 17.

There were few pictures on the walls or knickknacks on the end tables in the Miller home, but there were several books about Hitler, which Miller made his sons read, Connie said. Miller also paid them $5 a day when they were boys to work out so they would grow up to be strong white men, ready at any moment to fight for the race.

“My Dad’s father, his mother, actually came over from Israel,” Connie told the Report. “It’s funny that Frazier thinks he knows so much, because he would always tell me that I was like a model white girl. I didn’t really know what he meant. But we are descendants from there, so he obviously doesn’t know what he’s talking about.”

Below the “88” Miller put on his son’s headstones, he added his grandson’s name — the next generation of Aryan warriors. But soon after Mike died Connie took her infant son and fled Miller’s home, refusing to allow Miller to spend another minute with his grandson. “I didn’t want my son to be taught all that hate,” she said. “Honestly, I feel the way that Frazier raised Mike is part of the reason Mike died.” Connie was also afraid that if Miller found out about her family’s connection to Israel, Miller might do something to harm the child, “because he’s not what Frazier calls purebred.”

Being “purebred” wasn’t always so important to Miller. When he was a “brainwashed social liberal” in the military in his 20s, Miller married a Hawaiian woman and they had a daughter, a fact his rivals in the racist movement have used to brand him as a “race mixer.” The charge has dogged Miller for decades, and came up again after word spread years ago that police had caught him in the 1980s with a black transvestite prostitute called Peaches in his car. Miller does not deny he was with Peaches, but he insists his motive wasn’t race mixing. “I was carrying him out to whip his ass,” Miller told the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) last year, boasting that he had a “violent history of going around picking up n------ and beating the hell out of them, particular n----- f------.”

‘Just a Way Out’

The Thursday before the Sunday shooting spree, Miller stopped at the Aurora, Mo., home of 55-year-old Geraldine Perry to check on their business raising and selling French bulldogs for as much as $2,000 per puppy. “He’s just been a great friend,” Perry said of Miller. “We don’t talk no politics.”

They met through Perry’s late husband, Frederick, a former Klansman. “He was racist,” Perry said. “I’ll tell you that right up front.” When he died in 2010, Perry was flat broke. The pantry was empty, the electricity shut off. Miller, she said, got her into the dog business, “which kept a roof over my head.” He bought the dogs, the food, paid the vet bills. She helped him care for the animals and kept the female at her house.

Miller stopped by that Thursday to see if the dog was ready to mate. She was and Miller said he would return in a few days. “The next thing I know I see him on the TV,” she said.

A couple of days after that, her telephone rang. It was Miller, calling her from jail. “First time he called, first thing out of his mouth was, ‘Geraldine, do you hate me?’” she recalled him asking. “What could I tell the man? He’d done me nothing but right. I told him, ‘I don’t hate you. How could I?’ I do despise what he done. How could anybody not despise that? But I love you.”

Miller also stopped by about a month before the shooting. Perry said he told her his wife’s health was failing and “he was going to have to put her in a nursing home.” His health was also in decline, she said. Miller is reportedly suffering from emphysema and when he came to check on the dogs, “he couldn’t walk from the other side of the street to inside here to the table without having to stop and sit 10 minutes so he could breathe.”

She sighed and shook her head.

“I don’t know that man that done that,” she said. “It rips me apart. But why do people do what they do? I’ve wondered myself if it was just a way out for him.”

Hitler and the Klan

At his first court hearing two days after the shootings, Miller looked like a lost old man, trying to recall where he left his teeth. Wearing a scruffy beard and a baffled expression, he sat in a wheelchair, a sleeveless anti-suicide smock draped over him like an afghan. Until the shooting spree put him back on the racist map, Miller had been largely forgotten by his fellow white nationalists. When he was remembered, it was as a snitch, a rat, a disgrace to the white race for once testifying against some of the biggest names in American hate to save his own neck.

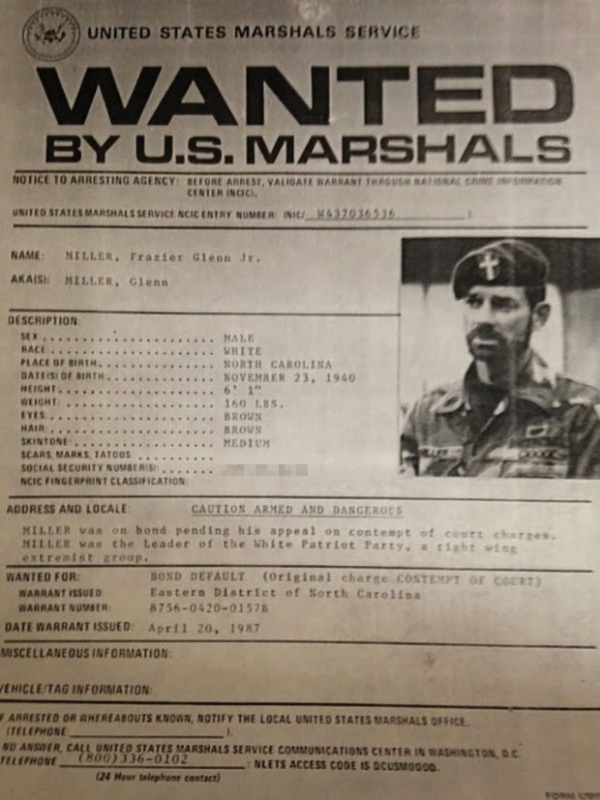

But time was when Frazier Glenn Miller was a racist superstar. A charismatic, hard-drinking — some say alcoholic — 20-year U.S. Army veteran, with two tours in Vietnam under his belt, Miller got invited onto daytime TV like “The Sally Jesse Raphael Show” to spew his bile. He ran for political office several times — getting clobbered every time — and, most chillingly, he marched through the streets of the South at the head of up to 500 Klansmen in army fatigues and combat boots, waving a sea of Confederate flags and shouting “white power!” He was tall, thin and dark-haired, more likely to be cast in a movie of the week as an Italian immigrant or Indian than the fair-haired Aryan avenger he so longed to be. “My racist and anti-Semitic thoughts consumed me every day of my life,” he wrote in his 1999 self-published autography, A White Man Speaks Out.

Miller was the Zelig of white nationalism. He was part of the nine-car caravan of Klansmen and neo-Nazis that drove through and attacked an anti-Klan rally in Greensboro, N.C., in November 1979. Miller admits to being scared and shaking. But as the protesters chanted “Death to the Klan,” Miller stuck his head out of the car window and shouted in his thick North Carolina drawl, “N------, Jew-K----, Communists bastards … you ugly Jew Yankee bastards… . Death to the Communists.”

Almost immediately, gunshots echoed through the streets of the Morningside public housing development where the rally began. The shooting lasted 88 seconds and when it was over five anti-racist demonstrators were dead or dying. Miller was never charged in what came to be known as the Greensboro Massacre.

In late 1980, after four years as a Nazi, Miller founded what grew to be the large and showy Carolina Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. While Miller had discovered calling himself a National Socialist was a hard sell in the American South, he nevertheless wanted to model his Knights after Hitler’s Nazi Party. “I would try to emulate Hitler’s methods of attracting members and supporters,” he wrote in his autobiography. “In the years to come, for example, I placed great emphasis on staging marches and rallies. It had been successful for Hitler.”

Miller’s southern-fried Reich only lasted a few years. In 1984, his “whole world,” as he put it, began to fall apart when he was sued by the SPLC for operating an illegal paramilitary organization and using intimidation tactics against African Americans. After then forming another Klan group, the White Patriot Party, he was found in criminal contempt of violating the court settlement in the SPLC case. He went underground while his conviction was under appeal. Using a rented copying machine he ran off hundreds of copies of his “Declaration of War” on “Jews and the federal government” and mailed them to racists, police and press across the country. The document exhorted Aryans to kill their enemies and awarded points according to their victims: one point for “n------,” 10 for “White race traitors” or Jews, 50 for judges and 888 for Morris Dees, co-founder of the SPLC.

He signed the declaration, “Glenn Miller, loyal member of ‘The Order.’” Although he was actually never a member of that now-defunct terrorist group, its members robbed $4.1 million from armored cars and distributed the proceeds among racist activists. Miller received at least $200,000 that year.

Within weeks of going underground, Miller, who had been hiding out in a trailer home in Missouri filled with weapons and ammunition, was captured by the FBI. He quickly flipped, cutting a deal with federal prosecutors to testify against white nationalist leaders at what became known as the Fort Smith, Ark., Sedition Trial. The trial was a disaster for the government, ending in acquittals for all 14 defendants. As for Miller, his testimony had been useless, which Miller has long contended was his plan all along. But a deal is a deal, so Miller only served three years in federal prison in upstate New York despite having been being indicted on weapons charges and for plotting robberies and the assassination of Dees.

A Legacy of Hate

Miller was released from prison in 1990, entered the federal Witness Protection Program, started driving a truck for a living and moved to Iowa with his second wife, Margaret, and their children. All told, the couple had five “younguns,” as Miller likes to say — three boys and two girls. Mike and Jesse are gone. His surviving son and namesake, Frazier III, never bought into his father’s “crap,” according to Connie, and moved away as soon as he could.

When Connie first met Mike she was just under 15, and Mike and his family used the last name Mays, not Miller or Cross. Sometime in the early 1990s, the family moved into a trailer home on about 40 acres of land between the nearly all-white towns of Aurora, population 7,500, and Marionville, with 2,200 residents, including Dan Clevenger, who ran a repair shop in Marionville and later became mayor for a short time. Clevenger and Miller became close friends, so close that two days after the shooting spree Clevenger told a Springfield, Mo., television station he “kind of agreed” with Miller “on some things, but I don’t like to express that too much.” A few days later, after a raucous City Council meeting, Clevenger was forced to resign.

When Miller wanted to build a bigger house, he sold off some of his land to a neighbor. The neighbor, Jim Carr, said Miller and his wife did some of the construction of the single-story house with a green roof and shingles themselves. That is the house Connie eventually moved into. At first, she was happy to do so. “Frazier taught me how to garden,” she said. “You’d think he was a normal guy except for the Hitler books and stuff laying around the house.” Connie had a terrible home life with her own family. Her stepfather sometimes slapped her around until one day Mike went over and beat him up. “He was the first person to ever stick up for me,” she said. “I think that’s what won me over.”

Mike not only protected her, he made her laugh. So did Jesse. The brothers, she said, had “bubbly” personalities, except when they were trying to please Miller.

Yet she wasn’t allowed to spend the night at the Miller/Mays home until, that is, she learned on her 17th birthday that she was pregnant. “I was pretty wild, I would say,” she said. “Didn’t come from a racist background at all, but Frazier and Mike’s stuff didn’t bother me. I kind of ignored it, until I had my son and then it was an issue. I started seeing the hatefulness and the hatred and it was wrong. Mike and me, we started having bad problems.”

Miller dedicates his autobiography to Mike, who he always called Michael, describing him a “Young Tarzan” and boasting that he “firebombed a Negro crack house and went to prison, and he did much, much more.”

Mike did indeed go to prison for arson. But otherwise, Connie said, Miller was lying about the incident.

“It was not a crack house at all,” she said. It was a trailer home where a black man and his white girlfriend from out of town were visiting friends. The black man’s presence around Marionville infuriated Miller and Mike, she said, so they decided to chase him out. “Everything that Mike and Jesse did or believed was encouraged by Frazier,” Connie said.

In the middle of a December night in 1995, Mike threw a Molotov cocktail into the back of the trailer home. Everyone got out uninjured, Sheriff DeLay said. Three months later, after some of his accomplices flipped, Mike was arrested. Then he was sent to a prison for young offenders for 120 days. “Frazier told him it was a badge of honor to go to prison, especially for a hate crime,” Connie said. “He was very proud of him.”

But Mike cried as he was taken away and when he returned, he had changed. “He was saved in prison,” Connie said. “He said he didn’t want to do that stuff anymore.”

Unfortunately, she said, Mike got swallowed up by drugs — meth, Valium, whatever he could get. “I remember him not sleeping, losing weight and getting into trouble with Frazier,” she said. “What did Frazier think was going to happen? Mike was encouraged to be violent and fight his whole life, so I think that was Mike’s escape route, the drugs.”

After Mike died, the family dropped the name Mays and went back to Miller. Connie packed her things and she and her son left for good. She tried to forget.

Then all the painful memories — the hate, the funerals, the lost love — came rushing back as she watched Frazier Glenn Miller on cable television, sitting in the back of a police car, shouting, “Heil Hitler.”