The Year in Hate and Extremism

The radical right was more successful in entering the political mainstream last year than in half a century. How did it happen?

After half a century of being increasingly relegated to the margins of society, the radical right entered the political mainstream last year in a way that had seemed virtually unimaginable since George Wallace ran for president in 1968.

A surge in right-wing populism, stemming from the long-unfolding effects of globalization and the movements of capital and labor that it spawned, brought a man many considered to be a racist, misogynist and xenophobe into the most powerful political office in the world. Donald Trump’s election as president mirrored similar currents in Europe, where globalization energized an array of extreme-right political movements and the United Kingdom’s decision to quit the European Union.

Trump’s run for office electrified the radical right, which saw in him a champion of the idea that America is fundamentally a white man’s country.

He kicked off the campaign with a speech vilifying Mexican immigrants as rapists and drug dealers. He retweeted white supremacist messages, including one that falsely claimed that black people were responsible for 80% of the murders of whites. He credentialed racist media personalities even while barring a serious outlet like The Washington Post, went on a radio show hosted by a rabid conspiracy theorist named Alex Jones, and said that Muslims should be banned from entering the country. He seemed to encourage violence against black protesters at his rallies, suggesting that he would pay the legal fees of anyone charged as a result.

The reaction to Trump’s victory by the radical right was ecstatic. “Our Glorious Leader has ascended to God Emperor,” wrote Andrew Anglin, who runs the neo-Nazi Daily Stormer website. “Make no mistake about it: we did this. If it were not for us, it wouldn’t have been possible.” Jared Taylor, a white nationalist who edits a racist journal, said that “overwhelmingly white Americans” had shown they were not “obedient zombies” by choosing to vote “for America as a distinct nation with a distinct people who deserve a government devoted to that people.”

Richard Spencer, who leads a racist “think tank” called the National Policy Institute, exulted that “Trump’s victory was, at its root, a victory of identity politics.”

Trump’s election, as startling to extremists as it was to the political establishment, was followed by his selection of appointees with anti-Muslim, anti-LGBT and white nationalist sympathies. To lead his domestic transition team, he chose Kenneth Blackwell, an official of the virulently anti-LGBT Family Research Council. As national security adviser, he selected retired Gen. Mike Flynn, who has described Islam as a “malignant cancer” and tweeted that “[f]ear of Muslims is RATIONAL.” His designated CIA director was U.S. Rep. Mike Pompeo (R-Kan.), who is close to some of the country’s most rabid anti-Muslim extremists.

Most remarkable of all was his choice as chief strategic adviser of Stephen Bannon, the former head of Breitbart News, a far-right media outlet known for promoting the so-called “alternative right” — fundamentally, a recent rebranding of white supremacy for public relations purposes, albeit one that de-emphasizes Klan robes and Nazi symbols in favor of a more “intellectual” approach. With Bannon’s appointment, white nationalists felt they had a man inside the White House.

That wasn’t all. In the immediate aftermath of Election Day, a wave of hate crimes and lesser hate incidents swept the country — 1,094 bias incidents in the first 34 days, according to a count by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC). The hate was clearly tied directly to Trump’s victory. The highest count came on the first day after the election, with the numbers diminishing steadily after that. And more than a third of the incidents directly referenced either Trump, his “Make America Great Again” slogan, or his infamous remarks about grabbing women by the genitals.

Several new and energetic groups appeared last year that were almost entirely focused on Trump and seemed to live off his candidacy. They included Identity Evropa, a campus-oriented group based in California; The Right Stuff, based in New York; and American Vanguard, a group with 12 chapters. And The Daily Stormer, the website whose chief came up with the term “Our Glorious Leader” for Trump, expanded into real-world activism by starting 31 “clubs.” In July, it became the most visited hate site on the Internet, surpassing longtime hate leader Stormfront.

It was, by any accounting, a banner year for hate.

Quantifying Hate

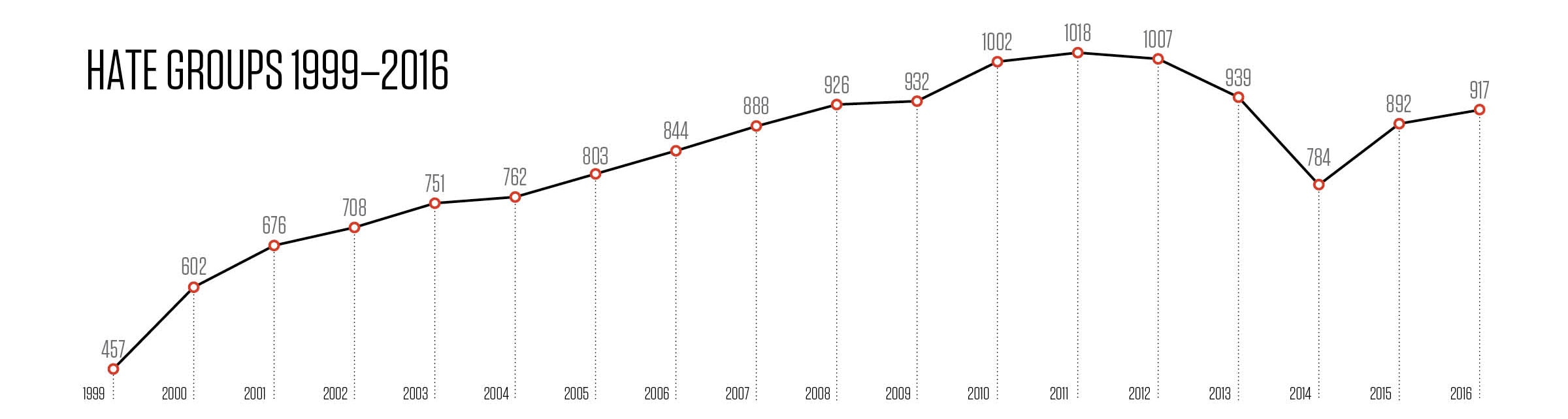

The number of hate groups operating in the country in 2016 remained at near-historic highs, rising from 892 in 2015 to 917 last year, according to the latest count by the SPLC. That’s only about 100 fewer organizations than the 1,018 tallied in 2011, which was the all-time high in some 30 years of SPLC counts.

And the numbers undoubtedly understate the real level of organized hatred in America. In recent years, growing numbers of right-wing extremists operate mainly in cyberspace until, in some cases, they take action in the real world. Dylann Roof, who was convicted late last year of the racist murder of nine black churchgoers, is an example of that — he had no real-world contact with hate groups before deciding, based on propaganda he read on the Internet, that it was time to start a race war.

By far the most dramatic change was the enormous leap in anti-Muslim hate groups, from 34 in 2015 to 101 last year — a 197% increase. But that explosion was not unexpected. Anti-Muslim hate has been expanding rapidly for more than two years now, driven by radical Islamist attacks including the June mass murder of 49 people at an Orlando, Fla., gay nightclub, the unrelenting propaganda of a growing circle of well-paid ideologues, and the incendiary rhetoric of Trump — his threats to ban Muslim immigration, mandate a registry of Muslims in America, and more.

The Muslim-bashing had consequences. Last October, three members of a militia-like group called the Crusaders were arrested and charged with plotting to blow up an apartment complex in Kansas where 120 Somali Muslim immigrants live. The attack was reportedly set for Nov. 9, the day after Election Day.

The number of neo-Confederate groups — organizations like the League of the South, which seeks a second Southern secession — rose by 23%, from 35 to 43 groups. But the number of Klan chapters fell 32%, from 190 groups in 2015 to 130 in 2016. Because the Klan groups’ numbers had expanded rapidly earlier, from 72 in 2014 to 190 in 2015, some constriction had been expected. In addition, much of that decrease was accounted for by the disappearance of the Militant Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, once the fourth largest Klan group in America, and the sharp reduction in the number of chapters in the United White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, which was the largest Klan group in 2015, and in the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.

While the overall level of hate groups remained fairly steady, the period saw a noticeable drop in real-world extremist activities like rallies and violence — outside of the wave of celebratory hate incidents that came mainly from Trump supporters in the election’s immediate aftermath — even as online activity increased. There hardly seemed a reason to organize their own rallies when extremists could attend a Trump event filled with just as much anti-establishment vitriol as any extremist rally.

‘Patriots’ at the Precipice

The antigovernment “Patriot” groups were another story.

Composed of people who believe the federal government is plotting to deprive Americans of their liberties, the Patriot movement has in the past swollen when Democratic administrations, which they despise, are in power. When the Republican administration of George W. Bush was in charge, they fell off. Even before Trump actually won, energy was draining away from the antigovernment groups.

Trump’s co-optation of some of the Patriot movement’s key issues — resistance against any kind of gun control, as evidenced by Trump’s enthusiastic endorsement by the National Rifle Association, and his clear sympathy for the movement’s interest in transferring control of federal lands to the states — was part of the reason for the Patriot falloff. The fact that such a prominent candidate was leading the charge on their concerns resulted in many abandoning activism.

“At this point there is an overwhelming belief among those on the right that Donald Trump is going to be able to do what he promised to do,” the publisher of The Economic Collapse Blog wrote a month after Election Day, adding that interest in the “prepping” movement, which overlaps heavily with the Patriots, had “hit a multi-year low.” “It is almost as if the apocalypse has been cancelled and the future history of the U.S. has been rewritten with a much happier ending,” he said.

Stewart Rhodes, founder of a leading Patriot group called the Oath Keepers, agreed, telling Mother Jones magazine that he worried that the far right would become complacent under Trump and that its activities would peter out.

Earlier, the groups had skyrocketed from a low of 149 in 2008 to a high of 1,360 in 2012, in large part as a reaction to the November 2008 election of Barack Obama. Intensely focused on the federal government as its chief enemy, the Patriot movement swelled when the nation was led by a black man suspected of being a foreign-born Muslim and worse. But as 2016 progressed, Patriots increasingly grew hopeful that Trump would become the new face of the federal government.

In the end, the number of Patriot groups fell by 375, or 38%, plummeting from 998 groups in 2015 to 623 last year. Within that, militias, which form the armed wing of the Patriot movement, fell 40%, from 276 to 165 groups.

Another key factor in the decline of the Patriot groups was the standoff that began on Jan. 2, 2016, when an armed mob led by Ammon and Ryan Bundy seized control of Oregon’s Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. Though the Bundys and their father, Cliven, had engaged in a similar armed standoff in 2014 at their Nevada ranch without being arrested for more than a year, the Malheur confrontation went differently. Most locals quickly lost sympathy for the Bundy gang, and most of its members were arrested and charged with serious crimes after 41 days. One of their number was shot dead at a roadblock when he tried to pull a gun on officers.

Even though the principals of the Oregon standoff were acquitted last October in a shocking jury verdict, many in the movement saw the confrontation as signaling the government’s determination to crack down. And the Bundys all face another trial in February on felony charges related to the 2014 Nevada confrontation.

Finally, several major Patriot groups either collapsed or shrank. One of them, Get Out of Our House, disappeared with all 37 of its chapters. We the People, the country’s leading radical tax protest group, dropped from 91 chapters to one. And the Oath Keepers lost 71 chapters, going from 181 in 2015 to 110 last year.

That didn’t mean Oath Keepers weren’t active. Like hate groups, the Patriot movement saw a continuing move into cyber-activism last year. On Facebook alone, Oath Keepers were maintaining at least 323 pages associated with the group.

Behind the Election

The election of Donald Trump — and related developments in Europe — is the culmination of a series of long-developing trends. As the world has become more interconnected, our increasingly globalized economy has fomented huge migrant flows and severe shocks to the industrial sectors of most developed countries. (War in the Middle East also produced enormous Syrian refugee flows last year.)

In the United States, that has meant that the proportion of foreign-born residents has grown from 4.7% in 1970 to 13.7% in 2015. The latter percentage is comparable to the very high levels of the foreign-born seen in the early 20th century (14.7% in 1910 and 13.2% in 1920), when white nativism reached a peak that led to history’s largest Klan membership and the racist Immigration Act of 1924.

As part of the same trend, the proportion of non-Hispanic white people in the U.S. has declined rapidly, creating a crisis of white identity. While America was about 90% white from the colonial era right up through the early 1960s, it was 62% white by 2015 and predicted by the Census Bureau to fall to under 50% by 2043.

At the same time, economic sectors like basic steel and auto production have increasingly moved overseas, chasing lower wages in a world economy. This has disproportionately affected working- and middle-class whites in the Rust Belt and similar areas, with white suicides and drug overdose deaths hitting new highs. As manufacturing wages have fallen and higher education has become essential to make a living wage, income inequality has risen dramatically since the 1970s.

How did this all play out in last November’s election?

In its post-election analysis, The New York Times found that Trump’s victorious election coalition, in addition to conservative Republicans of the South and West, was composed of “millions of voters in the onetime heartlands of 20th-century liberal populism — the Upper and Lower Midwest — where white Americans without a college degree voted decisively to reject the more diverse, educated and cosmopolitan Democratic Party of the 21st century.”

Without a doubt, Trump appealed to garden-variety racists, xenophobes, religious bigots and misogynists — people not necessarily in any hate or related kind of group, but who still were antagonistic toward multiculturalism. And the numbers of those people have been rising, with studies showing anti-black racism among whites increasing during the Obama years. But bigotry was certainly not the only factor motivating Trump supporters; the Times post-mortem found that many saw in their candidate “their best chance to dampen the most painful blows of globalization and trade, to fight special interests, and to be heard and protected.”

None of this is to say that whites have it worse than most minority groups, particularly African Americans and Latinos. But as numerous sociological studies have shown, a person’s objective economic condition is less important in fostering anger than how that person is faring compared to expectations. Whites have long had it better than other groups, but that advantage is slowly being whittled away.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Right-wing populism, driven in part by the kind of conspiracy theories and bigoted thinking that was espoused by Trump during his campaign, has become the answer for many Americans and millions of Europeans as well. Populism is the idea, as scholars Daniele Albertazzi and Duncan McDonnell phrased it, that “pits a virtuous and homogenous people against a set of elites and dangerous ‘others’ who are depicted as depriving the sovereign people” of their prosperity and rights.

Translated for today’s situation, the elites are seen as a global plutocracy of self-interested politicians, media leaders and capitalists — or, in the case of Europe, as the well-paid leaders of the European Union. The “dangerous others,” meanwhile, are immigrants, Muslims, black people, Jews and virtually every other minority.

The June vote by 52% of the British electorate to quit the European Union (EU) is in very many ways a close analog to the Trump vote in the United States. Those who voted to leave the EU, which requires open borders and migration within Europe and has welcomed millions of refugees from the Middle East, were mostly older middle- and working-class whites from troubled industrial areas. Also, as in the U.S. after Trump’s victory, the United Kingdom saw a wave of celebratory hate violence — up 47% over a year before — wash over the island nation.

It’s hard to predict where all of this will lead.

On one hand, it does seem likely that Trump’s ostentatiously right-wing politics will continue to dampen the Patriot movement, as happened under the last conservative Republican administration. It is also possible that, like the Patriot groups, the number of hate groups will fall as members look to Trump to pursue their program. On the other hand, it seems certain that Trump will be unable to fulfill many of his harder-line campaign vows — to ban Muslims, build a 2,000-mile border wall, or deport up to 12 million people — and this could easily result in an explosion of anger from extremists who feel betrayed. Historically, it is in just such situations that disappointed extremists may resort to domestic terrorism.

One thing seems certain. The radical right is feeling its oats today in a way that few Americans can remember. There are very large numbers of Americans who agree with its views, as sanitized under the deceptive Alt-Right label, although many of them may be less visible than before because they are not affiliated with actual groups. Whether or not the movement grows in coming years, it seems indisputable that its views have a better chance to actually affect policy now than in decades.

What follows are more detailed looks at sectors of the radical right.

KU KLUX KLAN GROUPS

Klan groups last year received a great deal of media attention, due largely to the fact that many of their leaders backed Donald Trump’s candidacy. David Duke, easily America’s best known (former) Klan leader, spoke repeatedly of his support for Trump, saying at one point, “I’m overjoyed to see Donald Trump and most Americans embrace most of the issues that I’ve championed for years.”

Trump at first declined to denounce or disavow Duke, saying, falsely, that he did not know anything about him. (In fact, Trump had written in a 2000 New York Times op-ed that he abandoned his exploration of a presidential bid with the Reform Party that year because of Duke and two fellow extremists who were involved with the party.) But in the end, pressed by the media, he weakly disavowed Duke.

Nevertheless, Duke took advantage of the media attention he received to launch his latest bid for political office. Last July, he announced his run for the U.S. Senate seat being vacated by Sen. David Vitter (R-La.). But he lost badly in the open November primary, coming in seventh with 3% of the vote, or 58,581 votes.

Aside from those developments, the activities of Klan groups were largely limited to anonymous leafleting — an easy task, typically requiring only one person, that virtually guarantees media attention. The SPLC found that various Klan groups had distributed white supremacist flyers 117 times in 26 states last year.

One of the groups most involved in leafleting, the Loyal White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, was embarrassed last December when its imperial wizard, Chris Barker of East Yanceyville, N.C., and a California leader, William Hagen (aka William Quigg), were arrested for stabbing another member. As a result, Barker was absent from the parade celebrating Trump’s victory he’d planned for December.

WHITE NATIONALIST GROUPS

White nationalism — groups that share most of the ideals of Klan and similar organizations but generally avoid robes and neo-Nazi symbols in favor of a suit-and-tie approach — was the sector of the radical right that identified most closely with the Trump campaign. In fact, the Alt-Right was essentially a rebranding of white nationalism meant to make it seem more acceptable in the political mainstream.

William Daniel Johnson, the head of the American Freedom Party, got a great deal of press attention last year, due to his formation of the American National Super PAC to fund robocalls in support of Trump during the primaries. The calls, in states including Minnesota, Utah and Vermont, dwelled on familiar racist themes like the dangers of non-white immigration and the alleged perils facing the white race.

The white nationalist scene was also marked by the emergence in the public arena of Richard Spencer, who claims to be a serious intellectual concerned with serious problems, and has a think tank to prove it. Spencer received an enormous amount of press as a spokesman for the Alt-Right, but his raw racism was exposed at a speech he gave in late November. He ended the talk to a Washington, D.C., Alt-Right conference with the cry, “Hail Trump, hail our people, hail victory!”

Not only did those words evoke German Nazism (“hail victory” translates in German as “sieg heil”), but the Nazi salutes then thrown by several members of his audience seared the extreme nature of Spencer’s movement into the public mind.

NEO-NAZI GROUPS

Aside from the rise of Andrew Anglin’s Daily Stormer site and its real-world “clubs” — new chapters that profited directly from the Trump phenomenon — the year on the neo-Nazi scene was marked by a number of attempts to build new coalitions among groups. Several of them, like the Coalition of Aryan Organizations and the United Aryan Front, collapsed almost as quickly as they appeared.

That left what was first called the Aryan Nationalist Alliance and then was rebranded as simply the Nationalist Front. The unity effort was spearheaded by Jeff Schoep, leader of the National Socialist Movement, Josh Steever of the Aryan Strikeforce, and Matthew Heimbach of the Traditionalist Worker Party.

The coalition peaked at 26 mostly tiny groups, but that had fallen by year’s end to 16, reflecting the perennial infighting that characterizes the neo-Nazi scene.

The “Unity Statement” of the Nationalist Front, which describes Schoep and Heimbach as its leaders, is a fairly typical neo-Nazi screed emphasizing hatred of “the globalists and the Jewish banking elites” and calling for the creation of an all-white homeland within the current United States. What is most interesting about it is that it essentially adopts the so-called “third position,” meaning that it opposes both communism and capitalism. Using anti-imperialist and pro-worker language that sounds almost as if it came from the left, it describes its goal as an ethno-state based on “economic Social Nationalism” (national socialism, or Nazism, in reverse).

The document is reminiscent of the early days of the German Nazis, when the so-called Strasserites emphasized the “socialism” in national socialism. Later, the German Nazi Party completely changed course, allying with major capitalists. One Strasser brother was murdered, another fled, and the Strasserites were purged.

ANTI-LGBT GROUPS

After years of defeats on issues like same-sex marriage and gays in the military, anti-LGBT groups last year were thrilled by the election of Trump, who lost little time in naming advisers and others with virulently homophobic views. Trump’s selection as his vice president of Indiana Gov. Mike Pence, a longtime opponent of LGBT rights, was a real victory for the anti-LGBT movement. And the idea that Trump will select one or more Supreme Court justices who might roll back recent LGBT gains also gave these organizations new optimism. At the same time, the anti-LGBT right ramped up several different legal strategies. Pursuing a course begun years before, activists worked to install more so-called “religious freedom restoration acts” (RFRAs) in states and cities that would ensure goods and services could be denied to LGBT people on a religious basis. The most draconian was passed in Mississippi in April, allowing businesses and state employees and healthcare personnel to deny some services to LGBT people. But a federal judge enjoined it in June, saying it favored some religions over others.

Anti-LGBT activists also pursued ongoing efforts to deny transgender people access to public bathrooms and other facilities that correspond with their gender identity. The harshest of these was North Carolina’s H.B.2, which passed in March. The law reversed anti-discrimination provisions protecting LGBT people and made it illegal for trans people to use facilities corresponding to their identity.

Violence against trans people also hit a new high last year, with at least 26 apparent murder victims, surpassing the 23 killed in 2015. The SPLC has found trans women of color are the minority most victimized by violent hate crime.

BLACK SEPARATIST GROUPS

The sniper murder of five Dallas police officers in July brought new attention to racist black separatist groups, which grew from 180 in 2015 to 193 last year. That is because the shooter, Micah Johnson, had “liked” the Facebook pages belonging to the New Black Panther Party, the Black Riders Liberation Party and the late founder of the Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad, prior to his killing spree.

Although those organizations are hate groups that explicitly denounce white people, Jews and LGBT people, many on the right used the Dallas killings to unjustly accuse groups like Black Lives Matter (BLM) of fostering violence it had nothing to do with. Although BLM has raised issues of police brutality, it has never endorsed anti-white or anti-police violence, and it is not a hate group.

ANTIGOVERNMENT GROUPS

At the roadblock that was the beginning of the end of the January 2016 occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, Robert “Lavoy” Finicum, a spokesman for the occupiers, was killed by law enforcement officers as he refused to surrender. Prosecutors described the shooting as justified, and that seemed clearly backed up by video showing him reaching for what turned out to be a gun.

That didn’t stop the Patriot movement from furiously describing Finicum as a martyr, and suggesting that the government had deliberately murdered him. After his death, the SPLC counted 82 events around the country that pushed that narrative and called for action against the government. But the Patriots’ canonization of Finicum did little to invigorate the movement, as the declining group numbers show.

There was one very significant development in the Patriot world — the adoption by leading groups of hardline anti-Muslim ideology. Although evidence of that was widespread, the best example came in November, when three members of a Kansas Patriot group were charged with plotting to mass murder Muslims.

Heidi Beirich, Keegan Hankes, Stephen Piggott, Evelyn Schlatter and Sarah Viets contributed to this report.