America's Only Coup D'État

North Carolina honors an elected black government that was violently overthrown by racist whites 120 years ago.

Wilmington, N.C. — When the North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Advisory Committee voted to approve a new highway marker, they were faced with a herculean task: how to summarize one of the most catastrophic events in American history in a few lines of text. The necessary brevity of the statement, 12 lines comprised of 34 spaces each, seems hardly adequate to summarize a massacre led by white supremacists against the African American residents of Wilmington, North Carolina, in 1898 — the only time a successful coup has taken place on American soil.

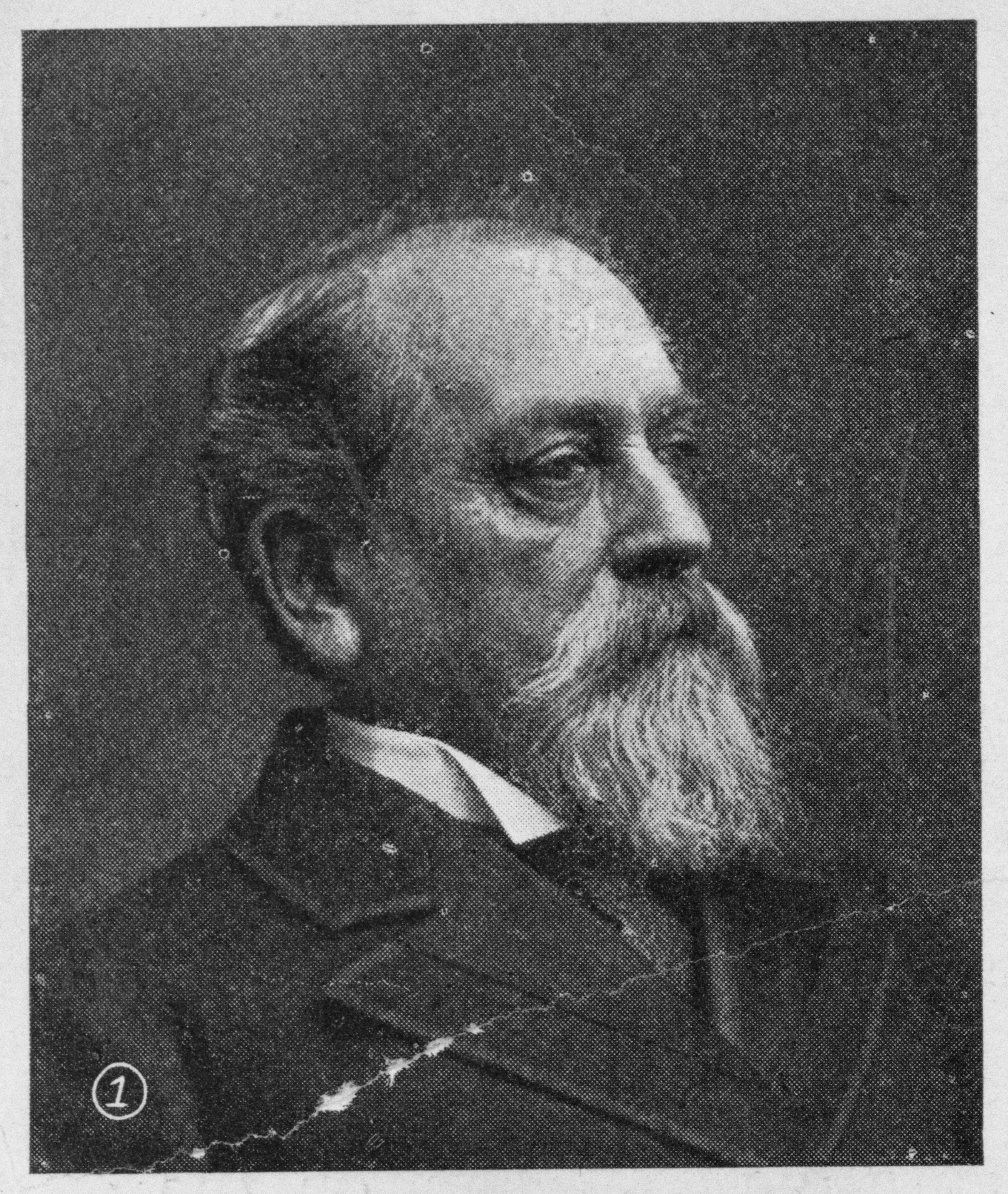

As is often the case when trying to encapsulate history, interpretations of the armed assault led by Confederate soldier and former U.S. congressman Colonel Alfred Moore Waddell against prominent African American businesses in Wilmington vary depending on the telling. Therein lies the challenge in memorializing it on a highway marker.

“Armed white mob met, Nov. 10,1898, at armory here, marched blocks and burned office of DailyRecord, black-owned newspaper,” reads the latest draft of the text. “Violence left untold numbers of African Americans dead. Led to overthrow of city government & installation of coup leader as mayor. Was part of a statewide political campaign based on calls for white supremacy and the exploitation of racial tensions.”

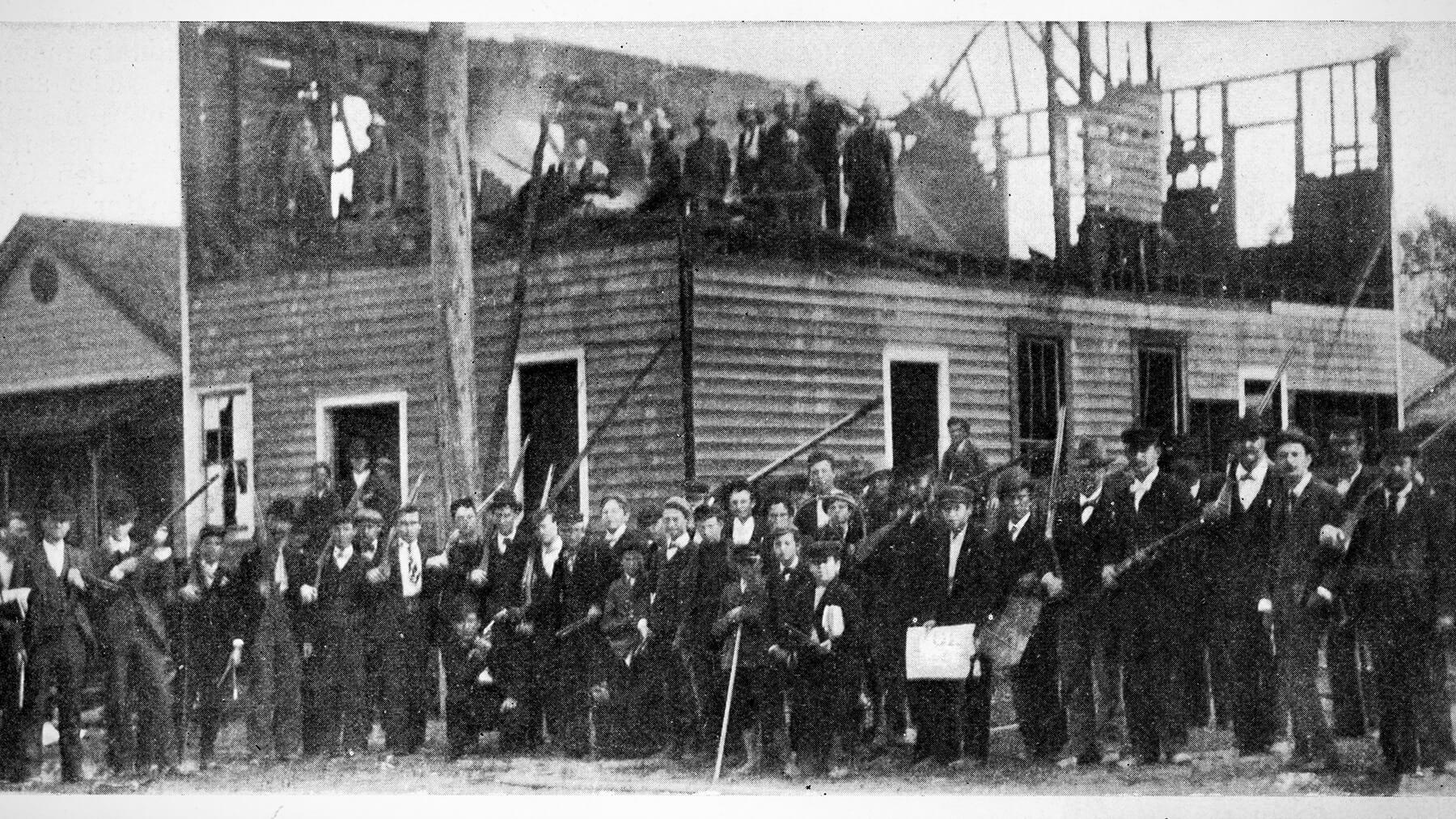

It tells a story, but not the entire story. The events of November 10, 1898 involved hundreds of white men taking to the streets to reclaim the city from the “clutches of Negro domination.” In an armed mob, they marched to the office of the African American newspaper, The Daily Record, and burned it to the ground. They then stormed Wilmington’s predominantly black neighborhood, and opened fire.

By the end of the day, many were dead, many had fled, and the culprits were left to tell the tale.

In 1896, 87 percent of eligible male black voters participated in the local election, which directly led to a number of African Americans being elected to office, and one of the first mixed-race municipal governments in the United States. Ahead of the November 8, 1898 elections, however, white supremacists openly encouraged people to “vote race, not politics” and ran campaign ads on the “White Man’s Ticket” with supported candidates in each district.

In the months leading up to the elections, one of the local papers, The Wilmington Messenger, repeatedly ran articles about real and imagined conflicts between the black and white residents. These articles followed a familiar narrative; that the quality of life of whites in Wilmington was being threatened by African American citizens, and/or that whites could retaliate with impunity.

“Negro Killed at Hamlet,” one headline screamed. “He insulted and assaulted a well-known white man who wore a red shirt,” was the subhead.

“News was received here yesterday of an incident which occurred in Hamlet Wednesday evening, which is but another illustration of the insolence engendered among negroes by the present Republican-negro regime ....”

Central to this theme was the idea that the black men in town posed a sexual risk to white women, and it was the responsibility of white men to protect them. On August 18, 1898, Alex Manly, the editor-in-chief of The Daily Record, published an editorial that railed against that hyperbole. “If the papers and speakers of the other race would condemn the commission of crime because it is crime and not try to make it appear that the Negroes were the only criminals,” Manly wrote, “they would find their strongest allies in the intelligent Negroes themselves; and together the whites and blacks would root the evil out of both races.”

Manly went on to say that white women fall for black men just as white men fall for black women, and that’s simply how it goes. However rational his argument, it was, at the time, sufficiently incendiary for the white supremacists.

But it was this line that truly set them ablaze: “We suggest that the whites guard their women more closely,” Manly wrote, “... thus giving no opportunity for the human fiend be he white or black. You leave your goods out of doors and then complain because they are taken away.”

In the ensuing months, it would be this editorial to which Waddell and his ilk would return, time and time again. They would use the myth of needing to protect the purity of white womanhood, and their outrage that Manly would dare use TheDaily Record to challenge them in such a way, to rouse the rabble.

On October 24, Waddell made a vigorous speech at the town’s Thalian Hall, in which he declared that he and his brothers “... wrote with their swords from Bethel to Bentonville the most heroic chapter in American annals and ourselves are men who, inspired by these memories intend to preserve at the cost of our lives if necessary the heritage that is ours.

“Let them understand once and for all that we will have no more of the intolerable conditions under which we live. We are resolved to change them, if we have to choke the current of the Cape Fear with carcasses,” he proclaimed. “Negro domination shall henceforth be only a shameful memory to us and an everlasting warning to those who shall ever again seek to revive it.” The speech was run the following day in the local newspaper, The Wilmington Messenger.

White supremacist Democrats continued to stoke tension in the days leading up to the election, urging their compatriots to end the control of the Populist-Republican coalition, also known as Fusion. Two days after the election, Waddell and his gang stormed the town.

The day after the massacre, the local newspaper The Morning Star proclaimed on its front page, “Bloody Conflict with Negroes. White Men Forced to Take Up Arms For the Preservation of Law and Order. Blacks Provoke Trouble.”

When it was all done, Waddell declared himself mayor and replaced with white supremacists the rightfully elected Board of Aldermen, as well as more than 100 police officers, market clerks, health officers, janitors of public buildings, the city clerk, the treasurer, the city attorney and anyone “whose affiliation with the Fusion-negro regime made them obnoxious to the people and the present administration.”

There is no official tally of the number of African Americans killed during the massacre. The North Carolina Office of Archives and History released The 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Report in 2006, which asserted, “No official count of dead can be ascertained due to a paucity of records from the coroner’s office, hospital, and churches.” Estimates range from 11 to 250. Hundreds more hid in the woods. The title of the report was problematic: “race riot” is the term Waddell himself used when describing the massacre, although it lacks veracity.

Highway markers are a regular sight in North Carolina, and in Wilmington, they seem to appear every few feet down the city’s main thoroughfares, many of which are also adorned with memorial Confederate statues. Amid the controversy over Confederate monuments, highway markers have remained largely unscathed, protected by omission from a state law, requiring the approval of the North Carolina Historical Commission before any monument, memorial, plaque or other marker on public property can be removed, relocated or altered. The law was signed in July 2015, just shy of a month after Dylann Roof killed nine African Americans at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina.

“The markers were successfully separated out, because they’re not monuments. But people think of them that way, unfortunately,” said Ansley Herring Wegner, the administrator of the North Carolina Highway Historical Marker program at the North Carolina Office of Archives and History at the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources.

“I try to encourage people not to think about historical markers as monuments. They’re more like labels on the landscape, like a history museum has a label text to point to something and say that’s what this is,” Wegner said. “I don’t want people to think about the markers as monuments, because we’re not making judgment calls on them.”

Unlike in other states, the highway markers program in North Carolina is state-funded; the $1,700 or so each marker costs to create and install comes from the Department of Transportation budget. Any resident can nominate a topic for a marker; a committee of history professors from around the state meets twice a year to vote on whether the proposed topic rises to the level of statewide importance. When he learned there wasn’t one commemorating 1898, Wilmington resident Rend Smith, a member of Working Narratives, a group that combines social justice and art, drafted a proposal.

The process is coordinated through Wegner’s office in Raleigh, and is typically fairly straightforward. The 1898 marker was expected to be, as well. As part of a standard procedure, Wegner emailed the elected representatives in Wilmington to notify them of a proposal in their district. Representative Deb Butler tweeted out the notice, and Wegner began receiving calls with feedback about the text.

“People didn’t like that we gave an entire line to Waddell. Some other people didn’t like that we said blacks instead of African Americans,” Wegner said. “That was just a space issue. We also originally had Alex Manly in there again, but since he already had a marker, we took his name out, and that gave us room to change the text again.”

One of the largest points of contention in the language was the line, “Violence left up to sixty blacks dead.” Some believe the number is much too high. Others, much too low. The latest draft reads “untold numbers,” which Wegner feels is more appropriate.

“Essentially what we’ve been hearing, and it’s absolutely legitimate and I’m glad it came around, is that this has been a long time coming and we want it to be right and respectful,” Wegner said.

Deborah Dicks Maxwell is the branch president of the New Hanover County Chapter of the NAACP, which includes Wilmington. She’s one of the people who objected to the original language of the marker, and felt that 60 was entirely too low.

“We know there was more than 14 because we know no one kept accurate records of black folks back then because no one cared about black folks back then,” she told the Intelligence Report in March, sitting in a sunny park outside the main branch of the Wilmington public library where a room devoted to North Carolina history contains archives of the original newspapers from 1898. “There were hundreds of people killed, hundreds more forced to flee Wilmington. Their land was stolen. You go downtown now and you see all these developments, and that’s all land that belonged to the black community.”

Dr. Melton McLaurin is a professor emeritus in the University of North Carolina at Wilmington’s history department. He has taught and written about the South and race relations for more than 50 years and thinks the number of dead has been “willfully exaggerated” over the years, and there were generally fewer than the 60 originally proposed for the marker. But, he says the number of actual dead is not as important as what he sees are the two defining factors of the coup.

“1898 is so terribly important because it clearly said the federal government is not going to protect the rights of African Americans, even if whites use violence against them,” McLaurin said. “It was part of an ongoing drive toward disenfranchisement of African Americans in the pre-Jim Crow era. Fear and violence were used to achieve this. And Wilmington signaled that the federal government isn’t going help.”

As for the size and scope of the massacre, that might never be completely knowable, or agreed upon. “At this point, it’s become a legend, powerful and emotionally true,” McLaurin said. “But as a historian I can’t teach in the classroom what I heard as a legend.”

McLaurin was part of the commission that established the 1898 Monument and Memorial Park in downtown Wilmington. Designed by Ayokunle Odeleye, it features six elongated, 16-foot-tall freestanding bronze paddles, and a curved bronze wall in a small park immediately off the highway. It was dedicated on November 8, 2008.

Maxwell thinks the park, like the marker, was a nice start, but there is a long way to go before the events of 1898 are properly addressed. “It’s not enough. As far as they’re concerned, they built that park and it’s a done deal,” Maxwell said. “We dropped the ball in Wilmington. We still have a long way to go.”

Both McLaurin and Maxwell want to see more education on the events of 1898, and how they helped set in motion a chain of events that still shapes race relations today. And there’s clearly a need. When asked, several local high-school and college-aged students said they had never learned of it. One librarian said she had only learned Wilmington’s history when she, a native North Carolinian, moved to Wilmington to study history at the university. She was amazed it wasn’t something she had learned in grade school, or in any of the years following.

“This city is beautiful but it has a lot of problems. The past impacts the future. You’ve got to acknowledge your past,” Maxwell said about the lack of education about 1898. “This city had a vibrant African American community, artisans, craftsman, fishermen, shop owners. We’re still vibrant but not as much.”

A highway marker isn’t likely to change that gap in knowledge anytime soon. Nor will all of the highway markers in North Carolina, lined from end to end. Some are far shorter than the long-form one for 1898. The marker for Thalian Hall, for instance, doesn’t mention that it was the site of the uprising, or any of the other historical events that occurred there. Nor does the marker for Alex Manly, which was recently knocked down in a traffic accident and is scheduled to be replaced this year. Wegner worries a similar fate will befall the 1898 marker.

“I’m having more and more [markers] vandalized. They’re vandalized, or they’re stolen for fun, because people want to have them in their home or over a bar,” Wegner said. “Or they’re stolen or vandalized because people don’t like the topics. They’re knocked over, they’re broken, they’re painted on.”

Wegner said the DOT has to occasionally break out the sandblaster, like when somebody painted KKK on the Thomas marker in December 2015. Wilmington’s Confederate statues, including those in the vicinity of the uprising, have also been vandalized.

On May 22, the North Carolina Highway Historical Marker committee held their bi-annual meeting in Raleigh. Maxwell and Smith attended via conference line from Wilmington to discuss the proposed language, as did Bertha Todd, a member of the 1898 Commission that oversaw the creation of the existing memorial.

Rend said he believed that the phrase “racial tensions” did not adequately reflect the role of the coup as a precursor to the Jim Crow era, and suggested “racial violence” or “racial hatred.” The committee settled on “racial prejudice.” Maxwell suggested the word “crowd” be changed to “mob” and reminded the committee of the importance of accurate language to Wilmington residents, who will pass the marker daily.

The marker was approved with the amended language.