The Invisible Hate Crime

Violence against people with disabilities is more widespread than you think.

What happened to Jennifer Daugherty couldn’t have been more cold-blooded.

The 30-year-old Pennsylvania woman with intellectual disabilities was smiley and trusting, a Steelers fan who loved dancing, scary movies, auto mechanics and making friends.

“She couldn’t sing, but she tried,” her stepfather, Bobby Murphy, said from the family home in Mount Pleasant, Pennsylvania. “She would play her radio in our backyard, and we had a couple of dogs, and she’d be singing and the dogs would actually howl along with her.

“Every day when I’d come home from work, she’d be standing at the mailbox waiting for me, just to ask how my day went.”

Jennifer was about to move out of her parents’ house and into her own apartment. She wanted what most anyone wants — independence, meaningful work, love and a family of her own someday.

“This is my time to make a new start for myself, and making some new friends and not being afraid of anything …,” she posted on her MySpace page in February 2010.

Three weeks later, her stepdad took her to catch a bus to Greensburg for a medical appointment and a sleepover at a friend’s place. That was the last he saw of her.

“I remember her exact words. She said, ‘Pa, I will see you tomorrow afternoon. Tell mom I love her.’ And she gave me a kiss on the cheek.”

At some point in Greensburg, Jennifer met up with six men and women, ages 17 to 36, who she thought were her friends. Over the course of two days, they took turns humiliating and torturing her in their crash-pad apartment. As she begged them to let her go, they beat her, stomped on her stomach, cut off her hair, painted her face with nail polish and forced her to swallow vile concoctions of detergent, oil, medications, urine and feces. Held captive in the bathroom, she was forced to write a suicide note before she was stabbed over and over with a steak knife, her wrists slit, her throat slashed. When still she clung to life, two of her killers wrapped a string of Christmas lights around her neck, and with one on each side, pulled. Then they stole a neighbor’s garbage can, stuffed her body inside, dragged it through the snow for two blocks and left it in a school parking lot.

It’s been eight years, and those who loved her are still reeling.

Murphy recalled how his stunned, overwhelmed family sat in front of a mortician’s desk after officials released her body.

“He was making notes,” he said, “and he looked at us, and he closed his binder and he said, ‘I’m just going to tell ya; they destroyed her body so bad that we can’t fix her, so she can’t have an open-casket funeral.’”

Although Jennifer’s killers were not charged with hate crimes, they were aggressively prosecuted and received sentences varying from decades in prison, to life without parole, to the death penalty.

The savagery Jennifer Daugherty suffered isn’t as rare as one would hope. The most recent analysis of a National Crime Victimization Survey by the U.S. Bureau of Justice indicates that people with disabilities are at least 2.5 times more likely to experience violence than those without. And much of that violence is extraordinarily cruel and sadistic.

When a crime is motivated by a person’s physical, intellectual or psychiatric disability, it’s a hate crime. But disability hate crimes in this country are woefully under-reported, under-investigated and under-prosecuted, said Jack Levin, professor emeritus at Northeastern University and co-director of the Brudnick Center on Violence and Conflict.

“When people think of hate crimes they think of neo-Nazis, they think of racism, they think of homophobia, they just don’t seem to think of people with disabilities as being a protected category,” he said by phone. “I call it the invisible hate crime.”

Levin has been studying hate crimes for more than 30 years. Although he holds himself somewhat responsible for coining the phrase, he doesn’t think “hate” is the best term since hate itself is not a crime.

“I plead guilty to having spread this misnomer,” he said. “Because in 1993, I co-authored the first book ever written about hate crimes, and guess what it was titled? Hate Crimes: The Rising Tide of Bigotry and Bloodshed. If we had instead entitled the book Bias Crimes it might have been more accurate. Everybody uses the term now, so it’s too late to change it. But a hate crime is a crime committed against a victim because the victim is different (with respect to race, color, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity or disability status). ‘Bias’ is more general; you victimize members of a group simply because they are different.

“And yet there are people very hostile toward people with disabilities. The sadism indicates some kind of need to feel powerful and special and important by targeting someone seen as inferior.”

In his book Disability Hate Crimes: Does Anyone Really Hate Disabled People? Mark Sherry documents case after case in this country and beyond of every type of brutality imaginable. He writes of people being tipped out of their wheelchairs, beaten with their own prosthetics, kicked in the head, slashed in the face, attacked with a tire iron, run over, stripped of their clothing, burned with cigarettes, urinated upon, smeared with feces, poisoned, drowned, stomped on, set on fire, disemboweled. It’s not a pleasant read.

“Writing this book has, in many ways, burned my soul with pain,” are his first words in the book.

“There’s never a time when I give a talk on this topic to the disability community when somebody doesn’t come up to me at the end to tell me their story of victimization,” said Sherry, professor of sociology at the University of Toledo. “I think disabled people have been segregated so much both formally and informally that they’re not placed in positions of power where people listen to their testimonies.”

Anyone who still needs convincing that there are people who hate people with disabilities can find proof with an online search and a few vile words:

“These people are barely people! They are wads of meat in the vague shape of people. Incapable of living any life whatsoever … if their parents knew they’d be downies, they’d have been coat hanger aborted into the toilet.”

“It’s gotten to the point where I will not even breathe in their disgusting direction. … They make me physically nauseous with their appearance, their behavior and their f------ stench. It’s ironic because I’m the most tolerant person I know but when it comes to these filthy pieces of shit I do a complete 180.”

While researching his 2010 book, Sherry found anti-disability hate sites and rants as bad as this, and worse.

“There’s been a campaign by disabled people to take these sites down,” he said. “Very successful, in general.”

And yet, there they still are.

Curt Decker, executive director of the National Disability Rights Network, was part of a coalition formed during the Clinton Administration that pushed for inclusion of people with disabilities in federal hate-crime legislation. It took a lot of convincing, he said from his office in Washington, D.C.

“In the political arena, there was a fair amount of conversation around, ‘People don’t hate people with disabilities, they’re very sympathetic.’ And it was like, ‘No, actually that’s not necessarily true.’ And then we went through a series of discussions like, ‘Well, isn’t it more a crime of opportunity? You rob a blind person or attack someone because they can’t run away? That’s not really hate, that’s just convenience.’ It was a constant struggle throughout the whole process.

“I was also very interested in trying to stretch it a bit because of who we are and what we do, which is a ton of investigations of abuse and neglect in a range of facilities where people with disabilities reside. ‘Wouldn’t that rise to the level of hate crimes?’ And a lot of people, again said, ‘No, no, no, that’s not a hate crime, that’s just neglect or bad staffing.’

“So, it was quite a slog. It took almost 12 years.”

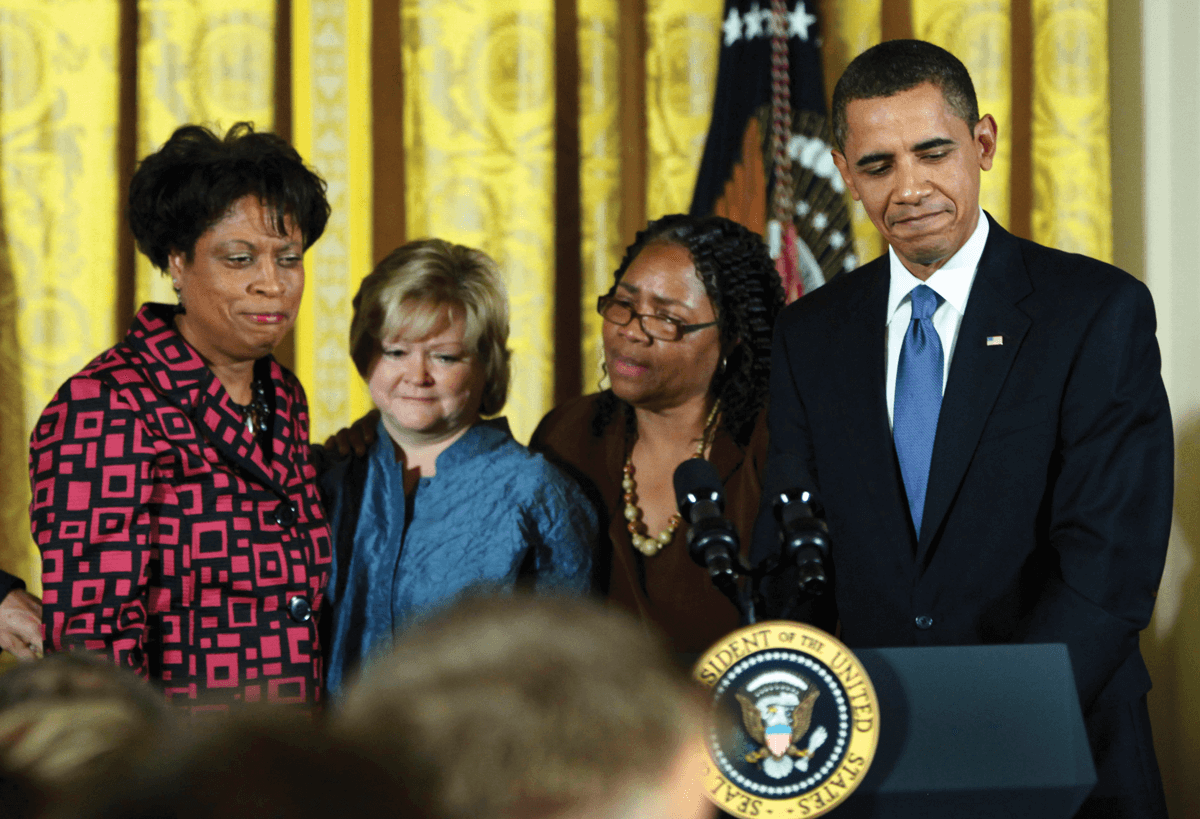

The fight paid off in 2009 with passage of the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, which expanded Civil Rights-era hate crime protections. Federal law now covers crimes motivated by a victim’s actual or perceived race, color, religion, national origin, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation or disability, and makes it easier for federal investigators to step in when local jurisdictions drop the ball.

Three New Mexico men were the first to be charged with hate crimes under the Shepard-Byrd Act. In 2010, after luring a 22-year-old Navajo man with mental disabilities to an apartment, they gagged him with a towel and used a hot coat hanger to brand a swastika into his arm. They also shaved a swastika into the back of his head and defaced his body with markers, writing “KKK” and “White Power,” and drawing horns on his forehead and an ejaculating penis on his back, calling it his “Native pride feathers.”

Although the defense characterized the crimes as pranks gone awry, all three attackers went to prison.

Harm doesn’t have to fit a legal definition to assault the soul.

Dominick Evans, a filmmaker and activist in Dayton, Ohio, is “multiply marginalized” as a transgender man who is also disabled. One of the worst days of his life came at 16, after returning to school following a back surgery he barely survived.

With progressive spinal muscular atrophy, he used a wheelchair and relied on an elevator to access his school. Well aware he was the only student allowed to use it on a daily basis, a group of football players littered the elevator floor with dead mice.

“They thought it would be funny to take the one disabled kid in their school and make them the senior prank,” Evans recalled.

“I spent sixth and seventh period hiding out in the disabled (restroom) stall because I couldn’t stand to go to class and they wouldn’t let me go home. I just cried. I felt like there was no place for me, that my life had no value.”

Nobody came forward to say who did it. Nobody was held accountable.

“Nobody cared about what happened to me; that’s how I felt, that nobody cared.”

The humiliation of this so-called prank contributed to a suicide attempt a few years later.

In 2015, in a school locker room in Dietrich, Idaho, a white high school football player kicked a coat hanger into the rectum of a black, mentally disabled teammate. The assailant, John R.K. Howard, had also repeatedly called his victim the n-word and taunted him with a song about lynching. The judge refused to see the case as a sexual assault or a crime motivated by race or disability. Howard, who got a plea deal, walked away with probation and community service. According to court records, the victim later ended up in an assisted living facility after multiple suicide attempts.

“They can’t see how our lives can be taken seriously,” said Vilissa Thompson, a Columbia, South Carolina social worker, a black woman with brittle bone disease and founder of RampYourVoice.com, a site promoting self-advocacy. “If somebody takes you as ‘less than’ or ‘subhuman,’ they are not going to take your quality of life and what happened to you as seriously as somebody they deem ‘worthy.’”

People with disabilities are a vastly varied, rich and diverse community. And they have been isolated, marginalized and dehumanized throughout history.

In this country, discrimination against people with disabilities, known as ableism, includes passage of “unsightly beggar” ordinances, later known colloquially as the “ugly laws.” Susan M. Schweik, author of The Ugly Laws: Disability in Public, traced the first arrest under these primarily anti-begging ordinances to 1867, two years after the end of the Civil War, when a “perfect wreck” of a disabled Union soldier wandering the streets of San Francisco offended certain people’s sensibilities.

Various cities across the country followed suit, including Chicago when an alderman became annoyed by what he characterized as a “street obstruction,” a woman who’d lost her job in a woolen mill after being run through a carding machine. With two children to support, she cranked “Molly Darling” on a hand organ day after day hoping for compassion. Instead, in 1881, Chicago passed an ordinance against people like her: “Any person, who is diseased, maimed, mutilated, or in any way deformed, so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object … shall not therein or thereon expose himself to public view …” Although rarely enforced, the last of these laws wasn’t repealed until 1974.

During the American eugenics movement, estimates indicate as many as 70,000 Americans deemed defective in one aspect or another were forcibly sterilized between 1907 and 1963. One mental institution in Illinois gave patients tuberculosis-tainted milk to weed out those genetically unfit to survive.

Adolf Hitler was a big fan of the U.S. eugenics movement. When forced sterilization spread to Nazi Germany, it became the precursor to mass slaughter. As the first victims of the Holocaust, an estimated 200,000 to 300,000 people with disabilities were among the millions killed in gas chambers and by injection, starvation, experimentation and exposure to deadly diseases between 1939 and 1945.

A mission “to rid the world of disabled people” was behind the biggest mass murder in Japan since World War II. In 2016, Satoshi Uematsu, a 26-year-old former employee of a residential institution in Sagamihara, Kanagawa Prefecture, broke into the facility in the middle of the night and started stabbing and slitting throats. Nine men and 10 women, from teenagers to senior citizens, were killed and 26 were wounded, most of them seriously.

Such atrocities are among the reasons activists on the frontlines of the disability movement sometimes bristle when non-disabled people question whether disability hatred really exists.

Lydia X.Z. Brown, an Asian-American activist with autism, has put it this way:

“We know hate and we know violence, because it is written on our bodies and our souls.”

Numbers gathered through the Bureau of Justice victim survey, which are reported anonymously, and those gathered by the FBI, which are not, are wildly out of sync. The most current FBI statistics claim only one percent of hate crimes indicate a disability bias, the majority against people with intellectual disabilities. Among reasons for the discrepancy is that state and local law enforcement agencies aren’t required to report them to the Uniform Crime Reporting program, which the FBI relies on for its data.

“We still get statistics from the FBI where all these major jurisdictions don’t report any hate crimes,” Curt Decker said. “I mean, Jacksonville, Florida? Miami? Zero hate crimes? We are constantly going back to these jurisdictions and saying, ‘Really? A major city didn’t have hate crimes against anybody?’ That’s pretty hard to believe.”

“For a long time, people with disabilities have been invisible when it comes to reporting about crime,” said Kim Brittenham, co-chair of the Violence & Abuse Subcommittee of the National Council on Independent Living. “The national crime victim surveys include people with disabilities but doesn’t include people with disabilities who are in group homes or living in institutions or hospitals. So, while the number of victims of violent crimes is much greater for people with disabilities, still, a lot of people with disabilities are largely invisible in the statistics.”

In January, after a year-long investigation, National Public Radio revealed in a seven-part series that women and men with intellectual disabilities are seven times more likely to be sexually assaulted than non-disabled people.

Dar Dobroslavic’s son was one of them, and she refuses to be silent about it.

Behavioral issues had always been part of his disability, but at 19, they went through the roof. After outings, he’d sometimes become violent when it was time to go home. At home, he’d come out of the bathroom swinging. And it kept getting worse.

“It was a runaway train at that point,’ said Dobroslavic of Tucson, Arizona. “We couldn’t read the signs.”

Then one night in 2002, her son pulled a knife on one of his caregivers and chased him out of the house. Four years later, he finally revealed that this caregiver had molested and raped him. By then the perpetrator was long gone.

Devastated, Dobroslavic reported the crimes, but too much time had passed, the detective told her. There was no proof, and her son had trouble talking about details.

Crimes against disabled people go unreported for many reasons. Some may not understand or have words for what’s happened to them. Or they’ve been threatened. Or they’ve had negative interactions with law enforcement or the justice system, and have no faith in the process. That can be especially true for people of color. Victims may fear retaliation, particularly if their perpetrators are caregivers or family members they rely upon for assistance. Or, reporting is impossible because they’re chained to a boiler in a dark, dank Philadelphia basement.

This was among atrocities discovered in the “Tacony Dungeon Case,” a crime ring uncovered in 2011 that kidnapped mentally disabled people and held them captive to steal their Social Security checks. For 10 years, the perpetrators isolated, confined, tortured, starved, drugged, stabbed, burned and beat their victims with everything from fists to hammers. Some were forced into prostitution. Some died. According to news reports, victims were so terrified they begged not to be set free for fear of being punished. The ringleader pled guilty to 196 federal counts, including hate crimes, and was sentenced to life in prison plus 80 years.

Victims also stay silent for fear no one will believe them. No one believed Nancy Jensen when she sounded the alarm about the Kaufman House, a group home for people with mental illnesses in Newton, Kansas, where she spent a year in the late 1980s.

When she moved in, a resident warned her about Arlan Kaufman. “‘Don’t make him mad, he’ll make you naked,’” Jensen recalled from her home in Wichita, Kansas. It didn’t take long to find out what that resident meant. Due to some infraction, Kaufman took away Jensen’s clothes and locked her in a room with boarded up windows, with limited access to a bathroom and nothing to sleep on but a filthy, orange shag carpet.

“I got put in seclusion three or four times,” she said, “one time for three weeks.”

Jensen tried several times to report what was happening in that house. No one took her seriously.

After she left, the abuse continued for another 18 years. Arlan and Linda Kaufman were indicted in 2004. Residents told of being forced to perform labor in the nude, of how Arlan had used a stun gun on one resident’s testicles and had urged them to masturbate and urinate in front of each other, as well as perform sex acts, some of which were videotaped. The Kaufmans were convicted in 2005 of 30 federal charges. Jensen was among those testifying, and later co-authored the book, The Girl Who Cried Wolf.

Eight years after Jennifer Daugherty never came home from her trip to Greensburg, it’s still not over for her family. Although all six killers were convicted, her family has had to sit through appeal after appeal after appeal. One of the death penalty cases was overturned, so they’ll be back in court in July. They dread it; they’re exhausted. It’s like having a lifetime admission to their own horror show.

“You never get a time to heal because there’s always something coming up,” her stepdad said.

Jennifer is home now, her ashes at rest in an urn on a living room shelf. Every morning when he walks by, he tells her good morning. Every night before bed, he tells her goodnight. Not a day goes by she isn’t loved and missed.

Nicole Jorwic is director of rights policy at The Arc, the largest organization in the country advocating for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities and their families. The Arc also runs the National Center on Criminal Justice & Disability. Jorwic spoke in May at a public briefing on hate crimes and bias-related incidents sponsored by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. Jorwic spoke with the Southern Poverty Law Center about her testimony at the event and what she hopes will happen next.

Crime against people with disabilities has been called “the invisible hate crime.” Why do people not realize it exists?

Because for decades people with disabilities were often locked away in institutions or kept out of mainstream society, it created an idea that people with disabilities were “less than.” Which is why hate crimes against people with disabilities are often minimized and called pranks or bullying instead of referring to them as what they are, hate crimes.

Is there any new legislation in the works?

We are always working on legislation to ensure that the civil rights of individuals with disabilities are protected. Specifically, we are working on a bill to create a national criminal background check system for direct care professionals who work with people with disabilities. Right now these are state systems, so a bad actor would just have to cross state lines to commit another crime. There are also continued legislative efforts, led by The Arc and the National Disability Rights Network, to fund additional training for law enforcement on how to interact with people with disabilities.

In certain situations, people with disabilities have been taught to be compliant with caregivers, teachers and others. How can that backfire?

Very often people with disabilities are taught to “be good” and not cause a problem. The unfortunate reality we know from data is that in a lot of crimes against people with disabilities, the offenders are people the individual knows. It can be difficult for the person to report in the first place. But for the person to be supported through the system, it requires them to step outside of that tradition of “being good” or doing what they are told.

Can you talk about assertiveness training and self-defense programs designed for people with disabilities?

There are several programs on self-defense, and sexual assault support groups and other support groups that are specifically geared toward people with disabilities. Some chapters of The Arc offer those support groups. Also, [these programs] can give individuals with disabilities a safe space to work through their issues.

What advice can you offer regarding reporting crime involving a person with a disability?

It’s very important that if there is any suspicion of any sort of abuse or crime against a person with a disability, that it’s reported quickly. But the reality is that the criminal justice system so often isn’t equipped to properly prosecute the crime. So if a local law enforcement agency were facing a situation like that, I would encourage them to interact with either their local Arc chapter or their state’s protection and advocacy organization that has expertise on how to work with people with disabilities. Because so often we see a lot of misunderstanding and misassumptions about an individual with disabilities being a competent witness — whether as a victim or as a witness to a crime. Arc or other protection advocacy organizations can support an individual to communicate what the person can’t. Not all people with disabilities can communicate everything they want. But they will communicate what they can in a way they know how, and often times that’s going to require a little bit of translation.

How can people get involved?

I would recommend anyone who’s horrified hearing these stories to get involved with their local chapter of The Arc or local chapter of another disability organization of their choosing, and to find a way to support the services needed for individuals to live in the community. Because the more people with disabilities are part of the fabric of society, the less we are going to have to worry about these issues because they will be out of the shadows.