Under Attack

As trans and gender nonconforming people are violently killed, a community struggles to trust law enforcement.

Her body came to rest in a second-rate motel room in a less than glamorous part of Jacksonville, Florida, 11 miles and a world away from the sand and waves of Jacksonville Beach. There were no dramatic goodbyes, no last moment with family, just the life and blood seeping out of 36-year-old Celine Walker. A single gunshot ended Walker’s life the night of the Super Bowl on Feb. 4, 2018. Walker was one of six trans women and gender nonconforming people killed in Florida in 2018 and among at least 26 in the United States whose lives were brought to a violent end. In Florida alone, along with Walker, the following were killed: Antash’a English of Jacksonville. Cathalina Christina James of Jacksonville. Sasha Garden of Orlando. Jessie Sumlar of Jacksonville. Londonn Moore of North Port.

Each died from gunshots or trauma.

Many of the victims were also black or Latinx — an estimated 82 percent of trans people murdered in 2018 were people of color, according to the Human Rights Campaign, which tracks slayings in the trans community.

That number follows a chillingly consistent trend in recent years. At least 29 transgender people were murdered in 2017, 23 in 2016 and 21 in 2015.

Since 2003, 117 transgender people died in violent attacks. Of those 67, 57 percent were killed with guns, the Human Rights Campaign reports. But those numbers are low.

“The statistics undercut the number of victims,” said Sarah McBride, the organization’s national press secretary. “It’s disappointing.”

When a transgender person is killed, a multitude of issues arise for the community and the law enforcement agency investigating the death, including how to properly identify a person who was born male, but identifies as female. Can the transgender community trust law enforcement agencies, some of which misgender the deceased? And how do investigators break through to a community that does not trust them?

A Complicated History

The LGBT community has a long and complicated history with law enforcement. It’s a fraught relationship exemplified throughout the twentieth century by all-too-common police raids of gay-friendly establishments. Same-sex relationships were illegal in many states, and at one point, the U.S. State Department listed LGBT people as “un-American” along with communists, anarchists and others who officials thought may be susceptible to blackmail and a risk to security.

The mistrust between police and the LGBT community came to an infamous breaking point in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, when four undercover officers raided the Stonewall Inn in New York City, a bar popular with LGBT patrons.

The raid and subsequent riots are considered a hallmark in the gay rights movement, but also in the uneasy relationship between the community and police. It’s a legacy that continues today as law enforcement departments struggle to connect with marginalized communities and overcome long-standing biases and mistrust.

Some of the mistrust comes from traditionally conservative police departments either being unwilling to engage with the transgender community or having a lack of experience with it, said Gina Duncan of Equality Florida.

Police officers generally don’t regularly meet with transgender people outside of making arrests, so they don’t understand the issues surrounding transgender life, Duncan said.

And because transgender people mainly interact with police during an arrest, the encounters tend to be something less than cordial.

“There still remains a real gap relative to trust,” Duncan said. “There’s still a lot of work to be done there.”

A New Life

Transgender women, particularly black and Latina women, are among the most marginalized in American society, and they are often in search of a new life, trying to escape rejection from family and friends and possible violence or other threats.

Transgender women may thus set out looking for new communities, stable employment and a chance to live as their true selves. However, a lack of legal documentation of their identities as women is a major hurdle to accessing resources that include employment and housing.

On social media and in interviews with newspapers and television stations, family and friends of the women who were killed described them as “gorgeous,” “beautiful” and “full of life.”

Naomi Michaels, a friend of 36-year-old Celine Walker of Jacksonville, Florida, remembered someone simply trying to make a life for herself in a conservative city of 892,000 people in northeast Florida.

“Celine was not a pageant girl. She didn’t even enjoy going to gay clubs or events,” Michaels wrote on Facebook as part of a plea for tips to solve Walker’s slaying. “She lived a low key life where she did whatever needed to be done in order for her to survive.”

And survival for marginalized transgender women often means going further to the margins of society, where the only kind of work they might be able to find is illegal and unregulated sex work, which can be dangerous.

The four women killed in Jacksonville were all sex workers, Duncan said, who for the most part had disconnected from their past lives.

It’s a world filled with transphobic people, where being a black transgender woman can be deadly.

“They are pushed into circumstances where they are likely to face violence,” said McBride, who made national headlines when she came out as transgender while serving as student body president at American University in 2012.

But each woman had pressed on in life, making new friends and creating a world to live in.

“I will no longer be a victim of discrimination. #Trans rights,” English wrote on Facebook on May 15, two weeks before she was killed.

Deadnaming

Sometimes, a name no longer fits the person.

For a transgender person, changing their name — either with legal paperwork or just among friends and associates — is a tremendous step away from a life they are choosing to leave behind.

It is also a way to establish dignity and a new sense of self.

“It’s a big step,” Duncan said.

Once a new name is established, many people don’t know the “deadname.” Respectful friends and family no longer use it, and others, also out of respect, don’t ask what it was.

So when police released the name of an 18-year-old man who was shot to death in Shreveport, Louisiana, on Aug. 30, those who knew Vontashia Bell may not have known the report was about her.

Police had misgendered Bell, a black transgender woman living in northwestern Louisiana, as the victim, and used her deadname in a press release picked up by local newspapers and television stations, further confusing and, ultimately, alienating friends and associates who might have had information that could have helped law enforcement find her killer.

Jacksonville investigators did the same with Walker, initially releasing her deadname to the public.

Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office spokesperson Chris Hancock told Mic: “He was a he per legal documents. … A lot of people are upset that we haven’t identified her as female when she wasn’t a female.”

The misgendering of Bell and Walker is part of a disturbing trend among law enforcement agencies handling the murders of transgender people. Between January and October 2018, a deadname was released in 11 of the 23 reported killings of trans people, demonstrating a lack of regard for transgender people and their communities. It also cements the long-standing mistrust of law enforcement from LGBT communities, which ultimately hinders effective investigations.

The deadnaming of a victim complicates the investigation, Duncan said. Many people know the victim only by their current name and may not realize a friend has been killed.

In Florida, where six of the transgender killings have taken place, police initially misgendered three of the victims.

“It is an indignity on top of the ultimate injustice,” McBride said. “It just breeds mistrust.”

In another high-profile case, local and federal officials misgendered 28-year-old Nikki “Janelle” Enriquez of Laredo, Texas, a victim of U.S. Customs and Border Patrol supervisor Juan David Ortiz.

Local District Attorney Isidro Alaniz has called Ortiz a serial killer who targeted sex workers. Ortiz has been charged with killing Enriquez and three other women in what authorities describe as a “serial killing spree,” targeting sex workers along the U.S.-Mexico border.

Complicating matters in the case of Enriquez was her family’s choice to use her deadname in the obituary, which may have delayed action from those who knew her as Nikki or Janelle.

“The deadnaming of victims … is totally against protocol,” Duncan said.

Monica Roberts, a writer and human rights activist in Texas, expressed frustrations with law enforcement misidentifying Enriquez in her blog, TransGriot.

“Been aware that we lost a trans woman since Saturday, but took me this long to confirm it because in large part of her being deadnamed and misgendered by Webb County law enforcement officials before they corrected it,” she wrote on Sept. 18. “Her life and the lives of the other cis feminine people … he callously took from all who loved them deserve justice.”

A Matter of Policy

Law enforcement agencies across the country have adopted policies regarding transgender communities. From St. Paul, Minnesota, to Jacksonville, Florida, departments in recent years are adjusting long-standing regulations and training officers to better understand and interact with transgender people and their communities.

The guidelines employed by multiple agencies are similar. They require police officers to use a person’s preferred pronoun; allow someone to request an officer of a specific gender to conduct body searches; require police to leave appearance-related items such as wigs or prosthetics in place unless safety is an issue; and they require departments to provide appropriate restrooms.

St. Paul police spokesperson Steve Linders told the Minneapolis Star Tribune that the department’s draft policy came about after dozens of similar policies from around the country were reviewed, including the U.S. Department of Justice’s guidelines on 21st century policing.

The Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office created a team dedicated to navigating LGBT issues and put a public outreach number on its website. The sheriff’s office did not return a message from the Intelligence Report seeking an interview.

Jacksonville Sheriff Mike Williams told television station WJCT News in August that a group of officers agreed to serve as liaisons to the transgender community.

“Quite frankly there was hesitancy on my part because how many teams are we going to have to establish?” Williams said. “However, it shouldn’t take a crisis like this, but because of this crisis, I think the team is an absolute necessity today.”

Even well-meaning law enforcement organizations struggle with best practices when victims are trans or gender nonconforming.

In the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, for example, a person is often listed by their birth gender, which may not be recognized by those who were closest to a transgender person prior to their death.

“Genetically, you cannot alter your sex,” said J. Todd Matthews, director of case management and communications for the federally funded organization.

Investigators handling a missing person or a case of an unidentified body can consider that the outward appearance might not align with the person’s sex at birth, Matthews said. And a note can always be appended to the file that can be seen when searching the agency’s database, he added.

“It’s a big consideration for sure,” Matthews told the Intelligence Report. “Same as race. Often people will identify as a race that is accurate, but not outwardly visible.”

Despite efforts of various agencies to adopt policies and work with the transgender community, the administration of President Donald Trump and Vice President Mike Pence has sought to impose new rules that would emphasize a strict sex/gender binary in legal and policy matters and eliminate any language that doesn’t fit a rigid male/female definition. This would further marginalize the more than 1 million Americans who identify as transgender.

The New York Times reported in October that the administration directed the departments of Education, Justice, Health and Human Services and Labor to adopt one definition of gender based on “immutable biological traits identifiable by or before birth.”

“The sex listed on a person’s birth certificate, as originally issued, shall constitute definitive proof of a person’s sex unless rebutted by reliable genetic evidence,” the memo stated.

If this policy change is tied to funding, it could be even more difficult for local and federal agencies to work with trans communities.

Slowing down the adoption of inclusive policies by local law enforcement only increases the chances of violence against those in the transgender community and the chance that crimes against them go unsolved. Transgender people already feel law enforcement “just does not get it,” Duncan said.

“All that stokes this kind of violence,” Duncan said.

Pursuit of Justice

While task forces and policies are a sign of progress, Duncan wants to see more done to solve the six slayings in Florida and prevent more in the future.

She helped convene multiple groups in a conference call over the summer to discuss the issues and has met with law enforcement officials in Jacksonville and Orlando in an effort to have the transgender and law enforcement communities collaborate.

“We need transgender women of color at the table,” Duncan said. “We need more voices speaking.”

Activists in the Sunshine State have called on then-Gov. Rick Scott to employ more resources to help find the killers, but according to Duncan, this has not happened. Scott’s office did not return a message from the Intelligence Report seeking comment.

The Florida Department of Law Enforcement has handled the forensic work on the six murders in that state. But Jessica Cary, a spokesperson for the agency, referred all questions about the killings and policies for working with the transgender community to local law enforcement.

“How can we disconnect from this cycle of violence?” Duncan asked.

Until she can answer that question, Duncan and others will continue to push for more investigations into the slayings.

And, they’ll keep working to keep the victims in the public eye.

Antash’a English

Antash’a English fell to the ground in a desolate place, her body riddled with bullets.

Police found the 38-year-old transgender nightclub performer between two abandoned houses in Jacksonville, Florida, on June 3, 2018.

She was injured in a drive-by shooting.

She could draw a crowd to the InCahoots Night Club. English lived for more than 20 years as a transgender woman.

A friend of English told First Coast News in Jacksonville that English won pageants for her performances.

“She was an unapologetic, bold and loyal person,” Taliyah Smith told First Coast News. “We met years ago while at a gay pageant. We both were entertainers.”

English died at a Jacksonville hospital on June 3, 2018.

Cathalina Christina James

Two people went into the Quality Inn motel near Interstate 95 in Jacksonville, Florida, on June 24, 2018. An unknown man, later described as slim, black and with facial hair on his chin, met up with Cathalina Christina James that day at the motel, about seven miles west of where Celine Walker died earlier in the year.

Before long, only the man, who police believe drove a white Buick, left.

James, a 24-year-old originally from Bishopville, South Carolina, was shot to death and left behind in the motel.

She died from a gunshot wound, but police have released little other information about her death.

Deandra James described her sister as someone who “always found a way to steal the show.”

“All eyes was always on Cathalina basically,” Deandra James told WLTX-TV in Columbia, South Carolina.

Sasha Garden

Being beaten to death is a slow way to die.

Most of the time, there isn’t one quick blow that ends a person’s life. Instead, a series of strikes leads to internal bleeding and trauma.

It appears that 27-year-old Sasha Garden’s life ended this way.

Police found Garden, a sex worker in Orlando, Florida, behind an apartment building on July 19, 2018.

Friends said Garden had been striving for a better life.

Garden, a Milwaukee, Wisconsin, native, traveled, living off and on in Orlando for two years, trying to find the right place.

Garden was an aspiring hairdresser who had been saving money for transition-related health expenses, Mulan Montrese Williams, a friend of Garden, told the Orlando Weekly.

“She was a firecracker,” said Williams, an advocate for transgender women and an outreach coordinator for the HIV/AIDS organization Miracle of Love. “She didn’t hold her tongue for anyone or anybody.”

Police initially identified her as a man wearing a wig.

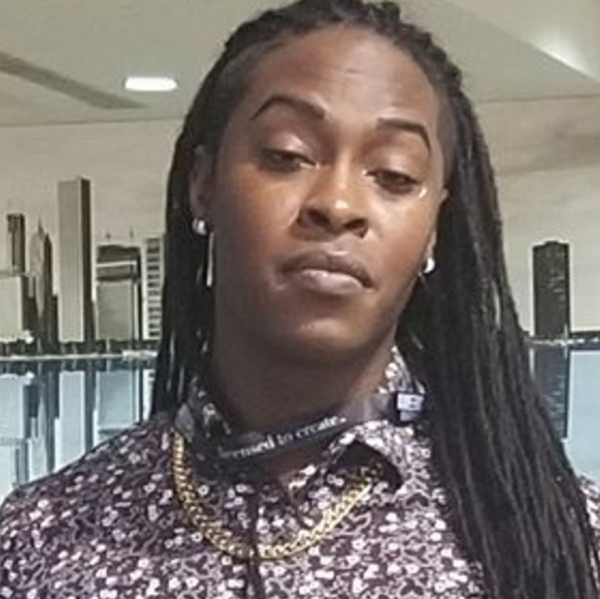

Jessie Sumlar

Standing in the doorway of his apartment holding a gun, 30-year-old Jessie Sumlar bled to death from stab wounds.

Sumlar’s wallet and car were gone from his Jacksonville, Florida, home, on July 16, 2018.

Sumlar, who performed regularly as a drag queen, identified as a man when not on stage but friends said he was gender nonconforming.

Twenty-six-year-old Omar Lewis, has been charged with murder in Sumlar’s death. As of November, Lewis was the only person charged for killing a trans or gender nonconforming person in Jacksonville in 2018.

On Facebook, where Sumlar, a cosmetologist at a salon, is pictured with long, braided hair, friends mourned his loss with crying emojis and disbelief.

“Rest in peace, beautiful,” Seth Nicholas King wrote on Sumlar’s Facebook page.

Londonn Moore

Londonn Moore left the world face down in a grassy area on the side of a heavily wooded road in North Port in southwest Florida.

Moore, 20, died after being shot multiple times. Her body was found Sept. 8, 2018.

Moore had been to Tampa and Fort Myers in the days before the shooting.

But police, while offering a reward, have released little information about Moore’s death.

While family members and police referred to Moore by her deadname, friends at work and on social media knew Moore as a woman.

Patricia Jagels was her supervisor at PGT, a company that makes hurricane-proof windows. Jagels described Moore as “sweet and nice” and “very outgoing.”

“She loved life, to say the least,” Jagels told the North Port Sun newspaper. “She really, really was eager to work.”

This document has been edited with the instant web content composer which can be found at htmleditor.tools - give it a try.