Sovereign Citizens Movement Resurging

The 'sovereign citizens' movement, big in the 1980s and again in the 1990s, is making another comeback. And officials are worried

In the middle of the morning rush hour last July 8, a dapper, 49-year-old gentleman by the name of Angel Cruz tapped his walking cane against the pavement as he serenely orchestrated the armed takeover of a strip mall branch of the Bank of America in a Miami suburb.

Wearing counterfeit U.S. Treasury badges, 30 of Cruz's followers, including 10 armed guards, blocked the bank's main entrance, parking lot and drive-through lanes. They were fiercely loyal to their fashionable leader, and with good reason: As employees of Cruz's company, The United Cities, they'd been guaranteed lucrative jobs for 30 years and promised new cars while their mortgage, credit card and utility bills were to be paid off in full by their employer. Cruz paid for this largesse — or, rather, purported to pay — with fake bank drafts and fistfuls of "United States Private Dollars," a counterfeit currency he churned out in his Orlando, Fla., home.

As they cordoned off the Bank of America branch, the members of the United Cities crew were calm and officious, behaving as if they had every right to be there, which they apparently believed they did.

One week before the attempted takeover, Cruz had walked into Palmetto Bay, Fla., police headquarters and politely requested backup for his impending "eviction" of the Bank of America. To an incredulous police officer, Cruz handed over a "court order" signed and sealed by a "judge" from the "The United Cities Private Court." It referenced a pending $15.25 billion lawsuit against the Bank of America filed by Cruz the previous month in Miami-Dade County Court. Cruz claimed the bank had wronged him because an Orlando branch refused to cash $14.3 million in phony United Cities bank drafts. Taking his beef public, Cruz also had posted a YouTube video announcing his upcoming "foreclosure" of two Miami-area Bank of America branches while ranting about the Federal Reserve as "Satan's banking system."

"In his own mind, [Cruz] was exercising legitimate authority," Secret Service agent Jim Glendinning told the Intelligence Report.

With his three-piece suit, gold-rimmed glasses and red suspenders, Cruz appeared more like a caricature of a wealthy banker than an antigovernment extremist. But the United Cities leader actually personified a particularly flamboyant example of the so-called "sovereign citizens" movement.

Based on financial schemes, paperwork shenanigans and mind-numbing conspiracy theories, the sovereign citizens movement promotes the tantalizing fantasy that anyone can declare himself or herself above and beyond the jurisdiction of government by invoking arcane legal terminology. Its far-right ideology overlaps with and informs that of many anti-Semitic groups, militias, Christian Patriot outfits and other organizations of the American radical right. And now, after swelling for a time in the 1980s and then again during the 1990s, the movement and its ideas seem to be making yet another comeback, with thousands of followers making life miserable for judges, law enforcement officers and a host of other enemies. Court officials, scholars, police and prison officials are all reporting signs of a real resurgence.

In the case of Angel Cruz, the bank raid that capped his embrace of the movement's ideas quickly fizzled after local police arrested him later that morning for trespassing. Out on bail the next day, Cruz was indignant. He continued to taunt Bank of America officers with threats of seizing branches, while informing his followers in online posts that the whole affair was "a dispute between two banks."

Bank of America filed a civil suit against Cruz two weeks later. The following month, Cruz and his right-hand man William Marrero were indicted on federal charges of bank fraud. Cruz's response was to file hundreds of pages of pleadings filled with rambling jargon lifted from decades' worth of sovereign-citizen teachings. Boiled down to their bizarre essence, Cruz's documents argued that the U.S. government has no authority over him and implored the judge to defer to the "Constitution" of The United Cities. When the courts dismissed his pseudo-legal gibberish, Cruz fled Miami. At press time, he remained a fugitive.

Once More, With Feeling

The roots of Cruz's outlandish ideology stretch back to the Posse Comitatus of the 1970s, an ultra-right, anti-Semitic vigilante movement whose members denied the legitimacy of taxes and of the U.S. government, often filing millions of dollars in fake liens against perceived enemies. (In many states, citizens can file liens against property, often people's homes, that prevent that property from being sold until an outstanding debt is satisfied, even without proof of that debt.) After a Posse adherent killed two U.S. marshals in 1983, the movement largely faded. By that time, however, its core beliefs about sovereign citizenship had taken on a life of their own.

In the early and mid-1990s, the ideas of the sovereign citizens movement gained an ardent new following among antigovernment militia, white supremacist and other radical groups. The movement's so-called "paper terrorism" tactics, in fact, prompted new laws in dozens of states aimed at preventing the use of bogus liens and fake legal documents. More recently, in the late 1990s, the movement incorporated another pseudo-legal strategy, called "redemption theory," that claims the federal government has enslaved its citizens by using them as collateral against foreign debt. Like other theories of the movement, redemption offers a way for adherents to supposedly make fortunes with the use of certain documents.

Originally taught in seminars at remote extremist compounds, sovereign-citizen and redemptionist doctrine and tactics are now spread in online forums like suijuris.net or via DVD courses available through organizations such as Paper Advantage or Citizens of the American Constitution, two sovereign-citizen groups that instruct clients in the wording of the movement's nonsensical legal pleadings. Sovereign-citizen newsletters like American's Bulletin are popular within prisons. College radicals post sovereign-citizen videos on YouTube and MySpace.

What's more, some observers suggest, it could get worse.

The economic forces that fueled a surge in the sovereign citizens movement in the 1980s — a recession, a spike in interest rates and farm foreclosures — are finding echoes in the current sagging economy and mortgage crisis. Now, worsening financial turmoil, combined with new means of dissemination like the Internet, seem to have helped engender a reenergized sovereign citizens movement. The movement has proliferated beyond its traditional antigovernment base, expanding aggressively among an unlikely mix of black separatist fringe groups, disgruntled police officers and IRS agents, con artists capitalizing on the mortgage crisis, and wholly unclassifiable figures like Cruz.

"It's cyclical," said Jay Adkisson, a finance lawyer who runs the online watchdog Quatloos.com, which monitors and exposes financial and tax-avoidance schemes and frauds. "Anytime the economy is down, you see a resurgence of people blaming the government for what goes wrong."

A 'Resilient' Threat

Although hard numbers don't exist, Michael Barkun, a Syracuse University professor who has studied right-wing extremism in the U.S. for more than 20 years, says anecdotal evidence suggests that there are tens of thousands of followers of sovereign-citizen ideology in the United States. In a 2007 paper for The Journal for the Study of Radicalism, Barkun described the movement as "a stubbornly resilient subculture, a community of the alienated unlikely to disappear any time soon, and a troubling irritant to the rule of law at a time when we scarcely need any additional challenges."

On Jan. 11, 2007, FBI Director Robert Mueller sounded a similar note in testimony to the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. "The militia/sovereign citizen movement," he said, "continues to present a threat to law enforcement and members of the judiciary. Members of these groups will continue to intimidate and sometimes threaten judges, prosecutors, and other officers of the court."

Although Cruz's armed guards never pulled their guns while blocking access to the Palmetto Bay bank, other recent encounters between law enforcement authorities and followers of sovereign-citizen ideology have resulted in shoot-outs, the use of improvised explosive devices and, most commonly, threats of violence and retaliation directed at judges, jurors and law enforcement officials.

Last April, millionaire tax protester Robert Beale convened a "common-law jury" over his jailhouse phone in Minneapolis to threaten a federal judge. "God wants me to destroy the judge," said Beale. "That judge is evil. He wants me to get rid of her." (The use of so-called common-law juries dates back to the early 1970s, when the Posse Comitatus convened small groups of followers into "common-law courts" that, among other things, issued arrest warrants and subpoenas against local sheriffs and judges, often threatening violence if they did not reply. Many of those in the militia movement of the 1990s also set up common-law courts.)

Beale's common-law jury issued unjustified property liens and "arrest warrants" targeting U.S. District Judge Ann Montgomery. According to an indictment, Beale's goal was to dodge prosecution for tax evasion (he was eventually found guilty on seven counts of evading $1.6 million in back taxes) by violently intimidating the judge. "Once I take down Ann Montgomery, no judge in the whole court will have anything to do with me," Beale said, according to an affidavit filed by an FBI agent. Last October, three members of Beale's common-law group were convicted of threatening a federal judge.

Beale holds bizarre beliefs, but he has not been without his successes. He is an MIT grad who earned $700,000 a year as CEO of the Comtrol computer firm and served as the Minnesota campaign manager for televangelist Pat Robertson's 1988 presidential bid. From 2000 to 2002, Beale was on the board of the far-right news website WorldNetDaily. But his "court," which counted a retired police officer as its chief justice, was based on often absurd interpretations of Old Testament lore.

"God needs us to be like Gideon against the Midianites — 300 versus 120,000 men," Beale said in a recorded call to a member of his common-law court. "We rise up and God will take care of us." The name of the court that Beale believed he operated was a typical sovereign-citizen mouthful of gobbledygook: "Our one supreme court Common-Law court for the de-jure Ramsey: the county: Minnesota; the land a superior court for the People, original jurisdiction under Almighty Yahweh exclusive jurisdiction in and for confederation-government United States of America."

Penetrating the Prisons

Beale and other incarcerated sovereign-citizen activists meet plenty of willing recruits behind prison walls, where the movement is thriving, experts say. Mark Pitcavage, director of research for the Anti-Defamation League and an analyst of the movement, says many sovereign-citizen ideologues have successfully indoctrinated fellow prisoners. "The result," says Pitcavage, "has been a flood of 'traditional' criminals, ranging from embezzlers to drug dealers, employing sovereign-citizen theories in fruitless attempts to get themselves out of prison or, more dangerously, in attempts to retaliate against the public officials and law enforcement officers who put them there in the first place."

Prisoners are being reached in other ways, as well. America's Bulletin sells "The Prison Packet" to inmates for $22. A green, spiral-bound notebook, "The Prison Packet" reformulates sovereign-citizen theories for inmates, focusing on a nonexistent set of "prison bonds" that supposedly underwrite inmates' incarceration. By filing a blizzard of liens and complaints, the notebook promises, inmates can not only free themselves, but also walk away with hundreds of thousands of dollars. (Although outgoing prisoner mail is usually monitored, sovereign-citizen literature often slips by officials because the dense and often incomprehensible jargon they contain doesn't register as glaringly extremist.)

Sgt. Paul Hestekind of the Wisconsin Department of Corrections told the Report about one inmate who recently fell under the spell of "The Prison Packet." "He thinks once he gets all these bonds listed, he cannot be held liable to the laws of counties or states," said Hestekind, adding that he had only recently spotted signs of the sovereign citizens movement in Wisconsin prisons. "He believes he is going to be released," the official said, even though he's not eligible for parole until the 2030s.

Claiming to be the son of original Posse Comitatus members, the inmate last year convinced five other prisoners to file the same paperwork. Still, "They all rescinded theirs" when they learned that the inmate was put in isolation and written up for associating with a security threat group, said Hestekind.

In still other cases, redemptionists worm their way into the prisons through "religious" outreach. Beginning in 2006, Robert Fox, head of the House of Israel, a Texas-based sovereign citizens group, ran a prison ministry that recruited inmate clients for his sovereign-citizen legal practice, even though Fox was neither a lawyer nor a pastor. Police raided the House of Israel three times in May 2008, and Fox was arrested in December on charges of barratry, or improperly trying to solicit business for his legal practice, a felony under Texas law.

Officials in the Crosshairs

The apparently escalating levels of sovereign-citizen activity over the past three years has borne out predictions in a 2006 report by the National Center for State Courts of a resurgence in the antigovernment movement that frequently targeted judges in the 1990s.

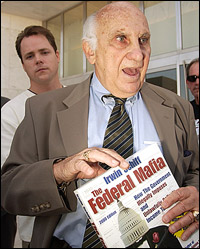

Speaking at the Nevada Federal Courts Media Conference last June, Nevada federal judge Kent Dawson described the harassment, vandalism and intimidation that marred the 2005 trial of Irwin Schiff, the "granddaddy" of the tax protest movement. In February 2006, Dawson sentenced Schiff to more than 13 years in prison for tax evasion and fraud.

Although the 80-year-old Schiff wasn't really a part of the sovereign citizens movement, many of its adherents promote his tax-evasion workbooks and Schiff hid his money through the anonymous "banking" services of the Oregon-based Christian Patriot Association. During the trial, IRS agents had acid splashed on their cars and court personnel had their tires punctured. One Schiff supporter was sentenced to a month in jail for verbally urging a juror to acquit, while another showed up during Sunday services at Dawson's church to harass the judge. During the trial, Dawson and his wife were escorted by federal marshals for their safety.

It was federal marshals rather than judges who were targeted in a prolonged 2007 standoff with New Hampshire tax protesters and former militia enthusiasts Ed and Elaine Brown. (Ed Brown, who once served time for armed robbery, had by then renounced his U.S. citizenship and declared his hatred for "Zionist Jews.") Scores of supporters, from unaffiliated fans to longtime leaders of sovereign-citizen militias, convened at the Browns' heavily fortified house in Plainfield.

After the Browns were finally arrested in late 2007 (they are both now in federal prison), four of their supporters were charged with trying to prevent U.S. marshals from seizing the Browns by stockpiling improvised explosive devices and aiming scoped assault rifles out the second-floor windows of their house.

Earlier this year, members of this "security team" were sentenced to lengthy prison terms. Among them was Robert Wolfe, 50, the Vermont state leader of the Constitution Rangers, a sovereign citizens group. Wolfe received a comparatively light sentence of 30 months after helping prosecutors build a case against Jason Gerhard, 23, Daniel Riley, 42, and Cirino Gonzalez, 31. Gerhard, Riley and Gonzalez had posted YouTube videos and MySpace blogs throughout the nine-month standoff, garnering a following among teenagers and college students. Gonzalez's MySpace blog inspired hip-hop tribute videos and gushing comments.

"I find that Mr. Gonzalez specifically went to the Brown residence prepared to intimidate, prevent and, and if necessary, kill members of the United States Marshals Service," New Hampshire federal judge George Singal said as he sentenced Gonzalez to eight years in prison last October. For their parts, Gerhard and Riley were sentenced to 20 and 36 years, respectively.

Scam Artists or Extremists?

The sovereign citizens movement veers wildly between the deadly serious —threats, bombs and sniper rifles — and the utterly ridiculous, like the notion that legal documents signed in red crayon are not subject to U.S. law.

That particular tenet inspired the title of Bombs, Taxes and Red Crayons, a forthcoming book by J.J. MacNab, an expert on sovereign citizens who has recently testified before the U.S. Senate and other regulatory committees on the growing violence and sophistication of sovereign-citizen movement adherents and other so-called tax protesters. (MacNab argues in favor of replacing the popular term "tax protester" with "tax denier," which, she says, better represents the movement's total disregard for both taxes and the legal consequences of evading them.)

MacNab believes there are effective ways to keep others from falling into the same pit as followers of groups like The United Cities. Among the recommendations she made in a 2006 report to the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance was that the IRS and law enforcement agencies counter sovereign citizens and tax protesters in their preferred locale — the Internet. For example, someone searching the Internet for "UCC sovereign taxes" or "redemption debtor" is led to a rat's nest of antigovernment extremist sites with very little factual information to counter their false propaganda. By contrast, someone entering "Nigerian investment E-mail" into an Internet search engine is immediately confronted with headlines and URLs that scream "scam" and "fraud."

Another problem, Syracuse University's Barkun points out, is that because sovereign citizens often seek money or valuables such as land, "they tend to be regarded by law enforcement as con artists" rather than politically motivated antigovernment extremists. "Yet this misses the point, for there is every reason to think that they believe what they say," Barkun says. That may be why putting sovereign citizen leaders in prison has typically done very little to temper their views. "My guess is that they are utterly convinced of the correctness of their legal position," Barkun says. "Or, failing that, that the cause is worthy of martyrdom at the hands of what they regard as an illegitimate legal system."

Typically, sovereign-citizen activity is not detected by law enforcement until a group has already started wreaking legal havoc. Many bogus liens are filed in rural county courts, where officials with little or no knowledge of the movement often fail to notice them. Fake incorporation papers, among other legal documents, can be filed digitally with state business bureaus with virtually no oversight.

"One of the most effective ways [of countering sovereign-citizen activity] is not to let it happen in the first place," says Pitcavage. "A bogus lien that never gets filed is just a harmless piece of paper; a bogus lien that is successfully filed becomes a frustrating weapon of retaliation. While some county recorder offices and secretary of state offices are good about refusing to accept bogus sovereign-citizen filings, other offices allow people to file all sorts of abusive documents. Some offices may be afraid of lawsuits, but the plain fact is that more harm always comes out of allowing bogus filings than out of preventing them."

Dethroning Sovereigns

There have been some efforts to fight back. The Michigan Judicial Institute, a training branch of that state's Supreme Court, offers a course on "managing pro se and militia litigants" to familiarize judges, clerks and court security with sovereign-citizen tactics and legal arguments. The National Center for State Courts suggests training court and business filing administrators with a "red flag" list of phrases to watch out for in filings, such as copyright symbols placed after a person's name and zip codes placed in brackets.

In court documents, Cruz, for example, signed his name as "Angel Cruz Durand@, UCC 1-308," an arcane reference to the Uniform Commercial Code, the set of U.S. commercial laws which, in the conspiratorial mindset of the movement's adherents, has replaced civil and criminal law. (According to this conspiracy theory, the U.S. went bankrupt in 1932 and ever since has used its citizens as collateral for foreign loans, hence the turn to UCC law.) Cruz also referred to the U.S. as the "UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, INC, a nonprofit Delaware Corporation, amended and Incorporated on 4/19/89." Sovereign-citizen adherents commonly believe the U.S. government, along with the CIA and the U.S. Social Security Administration, operate as religious nonprofits with no accountability.

Many of Cruz's victims — his former "employees," who transferred actual U.S. currency to Cruz's control in return for his extravagant promises — seem to still be invested in this mindset. The Report contacted several persons listed on fraudulent drafts issued by Cruz's organization only to have them immediately hang up the phone. "The loyalty that his victims continue to display to him is remarkable," said Secret Service agent Glendinning.

That's characteristic of the movement, says Pitcavage. "They just don't trust the government at all. As a result, many victims are credulous to the extreme, incredibly unwilling to admit they have been scammed. Others, even when recognizing that someone has taken their money, are still so hostile to the government that they have no interest in cooperating."

Cirino Gonzalez, one of the men charged in connection with turning the Brown residence in New Hampshire into a fortress, may have been a prime example of that stubborn intractability. Even as he faced the possibility of serious prison time, Gonzalez didn't hold back, ripping up a copy of the Bill of Rights on the witness stand and sarcastically telling the judge: "You want me to say I learned my lesson? I did. The lesson is you don't f--- with the government."