Wounded Victim of Racist Serial Killer Recounts Nightmare as Execution Nears

Before Joseph Paul Franklin, the prolific racist serial killer, is executed, Terry Jackson-Mitchell wants to look the condemned man in the eye and tell him she forgives him for the nightmares and flashbacks that crashed into her life on a summer night in Utah 33 years ago.

That’s when Franklin wounded Jackson-Mitchell, then 15, and shot and killed her two black friends, jogging a few feet from her in a Salt Lake City park.

“I believe in the old saying, forgiveness is a gift you give yourself,” Jackson-Mitchell, now 49, told Hatewatch in a telephone interview Sunday evening. “I forgive him based on what I’ve read about his horrific childhood. And I forgive him because I refuse to allow that night to define me.”

But her forgiveness only goes so far.

“I honestly wrestle with it, but I think he should be executed,” Jackson-Mitchell said. “I think he’s like a rabid dog. He’s suffered his whole life from cradle to grave. It just seems more humane to put him to death rather than let him live and suffer any longer.”

Franklin’s execution by lethal injection is set for Nov. 20 in Missouri. An 11th-hour legal challenge could, however, delay his trip to the death chamber.

While Jackson-Mitchell wants the sentence to be carried out as soon possible, Hustler publisher Larry Flynt – whom Franklin has confessed to shooting, as well as then-civil rights leader Vernon Jordan – does not want Franklin executed. Even so, as he wrote last week in the Hollywood Reporter, he would “love an hour in a room with him and a pair of wire-cutters and pliers, so I could inflict the same damage on him that he inflicted on me.”

Franklin has confessed to shooting Flynt in 1978 in Georgia because Flynt had featured a white woman and a black man in his magazine. Flynt was left paralyzed and in a wheelchair.

“I have had many years in this wheelchair to think about this very topic,” Flynt wrote. “As I see it, the sole motivating factor behind the death penalty is vengeance, not justice, and I firmly believe that a government that forbids killing among its citizens should not be in the business of killing people itself.”

A KILLER RECANTS

Last week, in a series of telephone interviews with Hatewatch from the condemned unit at the Potosi Correctional Center in Missouri, Franklin, now a 63-year-old grandfather, apologized to his victims and purported to renounce his racist past and extremist beliefs.

But Jackson-Mitchell said when she read the Hatewatch interview with the former Klansman and neo-Nazi she was stunned and skeptical.

“It’s hard to believe that he’s completely denouncing his racism and wants to ask for forgiveness from his victims,” she said.

Her skepticism is steeped in blood.

On the night of Aug. 20, 1980, Jackson-Mitchell, who is white, was a high school cheerleader and honor roll student out for a jog with another white teenage girl, who does not want her name known. They were joined by two black friends, David Martin, 18, a recent high school graduate, and his buddy, Ted Fields, 20, a college student and minister’s son.

Franklin was 30 and nearing the end of a lone-wolf campaign of murder and mayhem that began in the summer of 1977 with the killing of an interracial couple of Madison, Wis. His goal was to spark a race war as he drifted across the country, robbing banks and gunning down blacks, Jews and interracial couples – in broad daylight at point-blank range in Wisconsin and from the tall weeds and distant shadows in Utah.

Franklin was obsessed with “miscegenation.”

“I still don’t like it,” he told Hatewatch. “But now I know it’s none of my business.”

IT WAS SURREAL

It was close to 9 p.m. when Jackson-Mitchell and her friends began to jog around Liberty Park. It was Jackson-Mitchell’s first time jogging, and she and her girlfriend lagged behind the young men, who did everything together, from playing sports to going to church.

A car pulled up alongside the girls. The driver asked them if they wanted a ride.

“He said he just wanted to talk,” Jackson-Mitchell said. “I just knew this man was scary.”

The man was Joseph Paul Franklin.

The girls said no and ran to catch up with the young men. Franklin drove off into the night.

After finishing their jog, the four friends headed out of the park. They were crossing a street when Jackson-Mitchell felt something hot strike her arm. She thought someone had thrown a burning a firecracker that hit her.

“My arm was immediately on fire,” she said. “Dave looked at me and said, ‘They got me.’ I thought he was joking. It was surreal.”

Franklin was shooting from the four-foot-high weeds in a nearby vacant lot. His first shot hit David Martin and apparently passed through his body. Jackson-Mitchell said she was wounded by fragments when the bullet hit the street.

“Dave turned and fell,” Jackson-Mitchell said. “We all caught him. The shots just kept coming.”

Franklin fired a half dozen times, hitting Ted Fields, “who told me to run,” Jackson-Mitchell said.

In a panic, she looked around for cover, some place to hide. She dashed toward the tall grass across the street.

She was running directly toward Franklin.

“I was five or 10 feet away from him,” Jackson-Mitchell said. “I can’t believe he didn’t kill me, too.”

The girls survived. The young men did not. Franklin vanished.

“Their families blamed us,” Jackson-Mitchell said. “I wasn’t allowed to go to the funeral. I was alive and they were dead.”

There were whispers around town that the white girls had set up Ted and Dave. Jackson-Mitchell’s father was the president of a motorcycle club. Fingers were pointed at him, too. Jackson-Mitchell said white people asked her point blank, why was a pretty white girl like her hanging out with black boys? They warned her she was ruining her chances of finding a good white husband.

“Given the times,” writes Salt Lake City journalist Peg McEntee, “the racial divide was as deep here in Salt Lake City as anywhere in the nation.”

There were threats and strangers slowly driving past Jackson-Mitchell’s family home. The sniper was still on the loose.

“We couldn’t stand by the window,” she said. “It was pure hell.”

For her safety, Jackson-Mitchell’s parents moved her out of state to live with her grandparents.

“I lost a lot of friends,” she said.

The nightmares followed her.

SUFFERING IN SILENCE

Franklin has been convicted of killing eight people in his terrorist assassination campaign from 1977 to 1980, including Jackson-Mitchell’s friends. “Both of them, they were a joy,” Jackson-Mitchell said. “Dave was hysterically funny. You know that person in high school you can’t wait to see because you’re going to be laughing all day. He was just a light.”

Jackson-Mitchell testified at Franklin’s trials in federal and then in state court, where he received two life sentences. As she testified, she said she never took her eyes off of Franklin. He locked eyes with her only once.

All told, authorities believe Franklin may have murdered as many as 20 people across the country. But he has received only one death sentence. That was for the sniper killing of a 42-year-old Jewish man, Gerald Gordon, who was coming out of a synagogue in suburban St. Louis when he was shot and killed in 1977.

Jackson-Mitchell suffered in silence for years. She kept her past a secret. “I never told anybody,” she said, “that I was the girl shot for race mixing.”

She sought counseling and was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. She fought hard to be a survivor, not a victim. Jackson-Mitchell has also been speaking out more and more about the evils of racism. She and the families of her murdered friends made up.

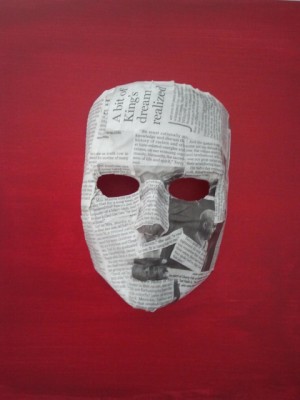

Every year she returned to the park on the anniversary of the shooting to say a prayer for her friends. A successful real estate agent, two years ago, Jackson-Mitchell went back to school and discovered the healing power of making art. She made a mask out of old newspaper clippings from that terrible night. The mask represented what she had been hiding from so long.

“I went back to where we were shot on the anniversary again this year and I didn’t feel sad,” she said. “I felt healed. I didn’t have the flashbacks I normally have. I think the art helps me find the voice of that 15-year-old girl I tried to bury alive. I think the art helped her be heard.”

The newspaper clippings she has left over from her mask project she plans to burn in the mountains, the night before Joseph Paul Franklin is put to death.