Date Set for Suit Alleging Army Failures With FEAR Terror Group

In early March, a package filled with grief and pride was left on the doorstep of Tracy Jahr and her spouse, Jacquie Gilmore. Wrapped in cardboard and plastic, the package weighed nearly 20 pounds. The women had been waiting for it for years.

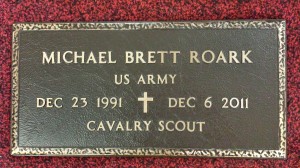

Inside was a bronze grave marker that read: “Michael Brett Roark US Army Dec 23 1991 + Dec 6 2011 Cavalry Scout.”

“At first I was angry when I saw it,” Jahr told Hatewatch last week from her home in Washington State. “I was flabbergasted. I felt, really, after all this time. The Army has been dragging its feet from the beginning. That’s why the kids are dead. But at least the marker is some recognition, recognition that Michael was a soldier. He wanted to be a one since he was a little boy.”

Roark was Jahr’s son and, like any parent, she worried she might never see him alive again when he joined the Army. The war on terror was raging overseas.

Her worst fears were realized two and a half weeks shy of her son’s 20th birthday when he was lured into an ambush, forced to his knees and shot in the head by terrorists. But he was not killed in the dusty streets of Iraq or the mountains of Afghanistan. Roark was killed in the Georgia woods, along with his 17-year-old girlfriend, Tiffany York, by a group of domestic terrorists, a renegade band of American soldiers, jacked up on drugs, PTSD nightmares and delusional plans to overthrow the government of the United States.

The killer soldiers have all been held to account, the ringleaders sentenced to life in prison for murdering the young sweethearts to keep the group’s plans secret. But Jahr and the family of York say it is time – past time – for the Army to also be held to account for allowing the homegrown terrorists to organize and grow right before its eyes, on the Fort Stewart military base, into a deadly antigovernment militia called FEAR. The group was led by a troubled but charismatic 19-year-old Pvt. Isaac Aguigui.

The families are suing the United States, arguing that Army commanders should have – and could have on numerous occasions – intervened in FEAR’s activities long before their children were killed in what the suit describes as “a heartbreakingly preventable tragedy.”

A few days after her son’s grave marker arrived, Jahr learned that a federal judge in Seattle had set a July 2016 trial date for the civil wrongful death lawsuit, which, in chilling detail, claims that “Army officials recklessly allowed FEAR to form and fester within its ranks at Fort Stewart, Georgia, despite abundant signs that Pvt. Aguigui and his cohorts were dangerous and mentally unstable soldiers in desperate need of arrest and treatment.”

In court papers, lawyers for the government replied to the suit, maintaining, “[T]he United States denies said allegations and puts the Plaintiffs to their proof.”

A First Murder Missed

Jahr and her ex-husband, Brett Roark, with the parents of York, Brenda Thomas and Thomas’ ex-husband, Timothy York, allege in their lawsuit that the most significant failure by the Army in preventing the wrongful death of their children “was also the most shocking.”

On July 17, 2011 – almost six months before Roark and York were killed – Aguigui murdered his wife, Sgt. Deirdre Aguigui, who was six months pregnant at the time. He strangled her in their home on Fort Stewart. Even before her death, the suit contends, “The Army was aware that Isaac and Deirdre Aguigui had a violent and troubled marriage.” Just three months before she died, according to the lawsuit, the sergeant went to see Fort Stewart’s lead advocate for victims of domestic violence and reported that she was “the victim of physical and verbal abuse by her husband, Pvt. Aguigui.”

“Like the murders of Roark and York,” the suit claims, “this was a preventable tragedy that should not have occurred.”

At the time of her death, the lawsuit says, “Sgt. Aguigui’s body showed signs of a struggle, including more than twenty bruises and scrapes on her wrists, arms, head, back and inside her mouth, as well as signs of a sexual assault.”

Army investigators initially suspected foul play. But when an autopsy, conducted by what the suit characterizes as an inexperienced military medical examiner, proved inconclusive as to the cause of death, Aguigui was not charged and the Army soon paid him more than $500,000 in military death benefits.

Aguigui used the money to fund FEAR, which stands for, “Forever Enduring, Always Ready.”

Drugs, Weapons and Crime

Aguigui, who like Roark, grew up in Washington State, went on a manic spending spree with his newly acquired blood money. He threw a large party at his house barely two weeks after his wife’s death. He purchased tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of military grade weapons, including rifles, explosives and the pistol that was eventually used to kill Roark and York. The suit says the FBI, after being tipped off by an Aguigui relative, alerted the Army to Aguigui’s weapons purchases. But the Army did nothing about it.

Aguigui dropped $16,000 in one night at a strip club called Temptations and thousands more on cocaine and other drugs. Aguigui, the suit says, used $6,000 of the money to bribe a sergeant who supervised his unit “in exchange for turning a blind eye to his dereliction of duty and criminal activity.”

With all the money and dope he was throwing around, Aguigui quickly became a magnet for other troubled soldiers, who he “wined and dined” and turned into members of FEAR with slick talk and a violent video game.

But when the death benefits began running low, according to the suit, Aguigui’s militia began engaging “in criminal conduct that was widely known within the Army.” They broke into cars and houses. Aguigui explored going into the drug business with a local drug dealer and even formed a plan to kill a competitor.

The Army, the suit says, did investigate the alleged murder plot, but “took no action to halt Aguigui’s crimes, despite overwhelming evidence that he had already killed his wife and was preparing for even more bloodshed.”

The Combat Veteran

In the fall of 2011, according to the suit, Aguigui and FEAR increasingly turned to Sgt. Anthony Peden for advice because of his combat training and experience. Aguigui may have talked a good game, but he had never deployed. Peden was the real deal, a combat veteran with two tours in Afghanistan. Peden brought home war stories and ghosts. He was haunted by what he had seen and done and suffered, the suit says, from “severe PTSD and traumatic brain injury [TBI].”

But instead of adequately monitoring and treating the broken soldier, the suit alleges, the Army left Peden to “drift into a dangerous fog of sleeplessness, self-medication, and severe alcohol and drug abuse.” Peden, the suit adds, began using heroin and living in the woods, spending “all of his money on drugs and alcohol.”

He would sometimes show up for duty drunk, yet the Army, the suit alleges, allowed him to continue officially training young soldiers. The Army should have known, the suit says, that “Sgt. Peden was an incompetent and psychologically disturbed soldier whose history of violence, rampant drug use, and untreated PTSD and TBI made him a significant danger to his fellow soldiers and civilians.”

The Criminal Trials

FEAR members often gathered at the Fort Stewart home of Pvt. Christopher Salmon, one of the ringleaders. There the group played video games and discussed poisoning the apple crop in Washington, blowing up a fountain in Savannah, Ga., and eventually assassinating the president of the United States.

Roark also spent time at the house and would sometimes bring York, a high school junior and photographer for the school yearbook. How much he knew about the group’s plans is unclear. He was planning to return home to Washington. Just days before he and York were killed, Roark had been discharged from the Army for, according to the suit, “minor misconduct that fell far short of the misconduct by Pvt. Aguigui, Sgt. Peden and Pvt. Salmon.”

From left, Pvt. Christopher Salmon, Pfc. Michael Burnett, Pvt. Isaac Aguigui and Sgt. Anthony Peden are led away in handcuffs after appearing before a magistrate judge at the Long County Sheriff’s Office in Georgia.

Roark and York were lured to the woods on the edge of Fort Stewart on the pretext of doing some night shooting with Aguigui, Peden, Salmon and another FEAR member, Private First Class Michael Burnett. Sometime between the last minutes of Dec. 5 and the first minutes of Dec. 6, 2011, Roark and York were killed. Peden shot York first and then handed the pistol to Salmon, who forced Roark to his knees and shot him in the head.

The bodies were discovered the next morning and the four killer soldiers were in custody in less than a week. Burnett quickly confessed and agreed to testify against his comrades, avoiding their fate of undoubtedly dying in prison. Aguigui and Salmon were tried in civilian court and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. Because of his war record and the demons that followed him home, Peden was sentenced to life in prison with the possibility of parole.

Aguigui was also tried in military court for the murder of his wife. Nearly two years after she died, the Army requested a vastly more experienced civilian medical examiner to review the case and he concluded, the suit says, that “Sgt. Aguigui’s injuries and death were most likely caused by a carotid sleeper hold, a form of strangulation the Army taught to Pvt. Aguigui.”

He was again sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

As they wait to hold the Army to account in court, Tracy Jahr and Jacquie Gilmore are looking for a new house. Once they find one, they plan to plant a willow tree for Michael in the backyard. Willows are strong and resilient like a soldier should be.

Underneath the tree, they will put Michael’s newly arrived grave marker and gather in the Willow’s shade, thinking of happier times when a little boy ran through the Washington woods playing Army.