People of Stormfront: Meet Freeland Roy Dunscombe, Don Black’s Radio Sidekick

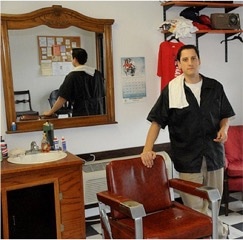

Every day, in thousands of small, rural towns across the American South, the local barber has generally been among the best-informed and one of the most influential opinion shapers in the community. He knows a few town secrets, probably has a few himself. And in Harrison, Ark., barber Freeland Roy Dunscombe is no exception.

On one recent weekday, just after 9 a.m., there was a steady stream of foot traffic at Dunscombe's single-chair barbershop in a former gas station in downtown Harrison. He was holding court, as usual, regaling his patrons with talk of psychology, philosophy, history and race -- as if he were married to the Ku Klux Klan.

And in more ways than one, he is.

“From an evolutionary perspective,” Dunscombe opined that day, “tribalism is a great strategy, and it far defeats nationalism.” He stepped back to run a brush through his electric clippers. “A guy who will go jump on a grenade to save his nation doesn’t have very good reproductive success.”

Such thinly-veiled racist conversation from a barber may be what many have come to expect in Harrison, population 13,324, a city whose Klan presence has put it on the map as one of the more racially divisive towns in America. But Dunscombe is much more than a garrulous barber who can riff on anything from politics to pomade.

For an hour each weekday morning, before he opens shop, Dunscombe assumes the name “Truck Roy” on Stormfront Radio as a co-host to former Klansman Don Black, who broadcasts a two-hour radio show from his dining room table in West Palm Beach, Fla. Dunscombe's role with Black, however, is much more than a verbal sparring partner.

An ideologue with a finger on the pulse of the movement, he serves as a bridge connecting Black to a new generation of anti-Semites, Klansmen, race conspiracy theorists and Holocaust deniers –– a bridge that Stormfront’s patriarch so desperately needs as younger racists look elsewhere online for a steady stream of hate.

Every Friday, for example, Dunscombe anchors a feature on Black’s program on the Rense Radio Network called “Five for Friday” to discuss issues of race and, more often, "white genocide." During one such moment in March focusing on “white tribalism,” Black and Dunscombe discussed what exactly white genocide meant. Did everyone have to die, Black wondered, for genocide to be the right word? Dunscombe responded, “There are still Tutsis left.” (The Tutsis are the second largest population group in Rwanda targeted for genocide by the majority Hutus.)

Their conversations on the radio are not always so … dynamic. In fact, there are times when enough tension is apparent between Dunscombe and Black to suggest their relationship may be one not of friendship, but of shared objectives –– racists from opposite sides of the generational divide and united by a crooked branch on a racist family tree.

Raised and homeschooled in Palomar Mountain, Calif., Dunscombe, 38, spent his early years living the nomadic life of a truck driver. He worked for Rock Solid Chugcreek Trucking in Wyoming before going to barber school in North Dakota. He then moved to Harrison, Ark., where – as he told the Southern Poverty Law Center – he moved “to follow a girl.”

Freeland Roy Dunscombe, back right, at a Knights of the Ku Klux Klan event in 2008. Dunscombe married Charity Pendergraft, 17, second from the right, the following year. Rumors about Derek Black, third from the left, and the "Pendergraft girls" surfaced around the same time. Their smiling mother, Klan TV host, Rachel Pendergraft, is on the far left.

Not just any girl, though.

On Nov. 12, 2009, Dunscombe married Charity Pendergraft, the granddaughter of Thomas Robb, an Arkansas-based Christian Identity pastor and head of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. They wed not quite six months after she turned 18, according to their marriage license. Dunscombe was 32 at the time.

With that marriage, Dunscombe earned a direct family relationship to one the country’s most infamous racists, and by luck or deliberate design, a connection to nearly every former head of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. His grandfather-in-law now leads the Klan group, which David Duke started before handing the reins over to Dunscombe's boss, Black, who ran the group until he was he was arrested for violating the Neutrality Act by plotting to invade a Caribbean island in 1981 and sent to prison.

But by the time of his wedding, Dunscombe had already been a fixture on Black’s Stormfront radio – a predecessor to the program broadcast on Rense. On that network, he hosted a show called “Riding Shotgun with Truck Roy.” With infamously racist in-laws, it was there that Dunscombe seemed to find a mouthpiece and truly started to talk.

“The only reason why our people have been disheartened and disillusioned and have been tricked into not standing up for themselves is because our controlled media and our society as a whole has tried to beat us down and tried to make the White race seem petty. And of course we're not petty. We're the grandest thing that's ever happened to this planet,” Dunscombe said during one broadcast on May 28, 2008.

But those early radio days –- when he was also broadcasting on Intercept Radio under the registered amateur radio handle of “KF5NBP” –- were only a glimpse of Dunscombe’s racist activism to come. After settling down in Arkansas, he started working hard to live up to the expectations of his Klan in-laws.

By 2012, Dunscombe had started to exhibit the beginnings of political ambitions. He ran as an independent candidate for justice of the peace in Boone County, hoping, it seemed, that a sprinkling of folksiness might sugarcoat his history. “I have never run for political office before, but as a barber I listen to a lot of folks,” he told the Harrison Daily.

Freeland Roy Dunscombe, left, in 2008, apparently helping the "men-folk" at the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan compound prepare for a cross burning.

While claiming not to be a member of the Klan, he couldn’t hide that three years earlier he had spoken at the Knights Party National Congress, held conveniently by his in-laws. In an interview he gave the Carroll County News in November 2012, four days before the election, Dunscombe’s views came into clearer focus.

“Our enemy is not black. Our enemy is not brown or Mexican. Our enemy looks just like us but has no loyalty to us,” Dunscombe said.

He lost handily to Ann Kimes, a Republic incumbent, who mocked Dunscombe for believing his views would have widespread appeal. “I really can’t take credit for winning the election. I just give him credit for committing political suicide,” Kimes told the Northwest Arkansas Democrat Gazette after Election Day.

But with the blessing of Black and Robb, political pitfalls did not slow Dunscombe’s rise on the radical right.

In 2013, at Stormfront’s annual retreat in Tennessee, Dunscombe shared the dais with David Duke, Sam Dickson and Timothy Murdock, the man behind White Rabbit Radio and the proliferation of The Mantra – a 221-word mini-manifesto written by Robert Whitaker, an aging segregationist with a history of drug and alcohol abuse. Murdock had been using his online radio platform to spread The Mantra far and wide, and it wasn’t long before it found its way to Harrison.

On Oct. 15, 2014, a bright yellow billboard with bold black letters appeared overlooking a well-traveled street in Harrison. The sign proclaimed in black letters, “Anti-Racist is a Code Word for Anti-White,” the final and most frequently quoted section of Whitaker's screed.

Freeland Roy Dunscombe, right, and Thomas Robb, second from right. (Credit: Jacqueline Froelich/KUAF)

It remains unknown who paid for the billboard. But eight months earlier, Dunscombe, Robb and others attended a meeting at the local library for the Harrison Community Task Force on Race Relations, established to repair Harrison's tarnished image as a stomping ground for those who promote racial hatred. During the meeting, Robb chastised the city, as usual, for its characterization of his racist beliefs. But it was his grandson-in-law, Dunscombe, who stole the show.

“It’s only white countries where people get called racist, and then as penance for their sin of being white, they have to bring in tens of millions of non-whites into their country,” Dunscombe said indignantly at the meeting.

On his chest he wore a sticker with a message no one had seen before –– Whitaker’s Mantra – and an exact image of the billboard that eight months later no one would claim, in the end not even Dunscombe.