Mother of Simcox’s Alleged Victim Recounts Nightmare Scenario in the Court System

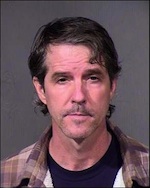

Ever since that night in May 2013 when her daughter told her that her friend’s daddy – the seemingly ordinary guy who hung out with the kids in the neighborhood, but who turned out to be former “Minutemen” leader Chris Simcox – had molested her the previous February, Michelle Lynch’s world has been an endless limbo of uncertainty while wrestling with her daughter’s pain.

It’s a feeling, she says, that has only been worsened by her experiences with the court system as she awaits the day when Simcox will stand trial more than two years after the event.

Lynch says her daughter, now seven, was a happy and well-adjusted little girl before that night in 2013.

“Before this event, [she] fell asleep with no problems and slept through the night,” explained Lynch in a letter to the trial judge, Superior Court Judge Jose Padilla. “She was very trusting; any complaints of feeling sick were far and few between and were due to true illnesses, and she was only emotional/angry when the time was ‘right,’ which was determined by your typical 7-year-old child.

“She now has nightmares and does not fall asleep without complaining of her stomach hurting. She also complains of being ‘sick’ when I have to leave her. She does not sleep through the night and most nights she finds her way into my room, even though she has her own room and bed. She worries about the doors being locked and asks over and over if they have been secured.”

In her letter, Lynch went on to describe a litany of changed emotional behavior, including “extreme sensitivity” and frequent crying, as well as extreme anger and occasional hitting. She described what should have been a fun trip to Disneyland transformed into a series of panic attacks.

“I realize that nightmares and separation anxiety may be typical of a young child's behavior and that many children will exhibit periods of emotional sensitivity and anger; these behaviors were never existent in [my daughter] prior to this happening to her,” she explained.

Lynch wrote her letter because she faces the horrifying prospect of having her daughter be cross-examined by Simcox himself, a prospect that very nearly became a reality when Padilla approved Simcox’s request to represent himself at his trial. Late last week, the Arizona Supreme Court intervened.

Lynch wrote the letter in March, hoping to persuade Padilla to agree to a prosecution request that Simcox be required to only cross-examine the girls through a court-appointed associate attorney.

“Her father and I continually do our best to help [the girl] through all of this by providing her with comfort, consistency, and other avenues that encourage her to work through this in a positive manner to where her daily life isn't effected,” Lynch wrote. “Allowing Mr. Simcox the ability to address my daughter, I fear, will only set [her] back in her healing and quite possibly exacerbate her symptoms and anxiety/panic attacks.”

However, Padilla ruled in Simcox’s favor, telling Lynch and the other mother in the case that their letters did not constitute evidence that the girls would be traumatized: “With all due respect,” he said, “[the mothers] are simply not qualified to make that assessment.”

That ruling, and the subsequent decision by the state appeals court to allow the trial to proceed even as it considered the legal propriety of allowing a pro se defendant to cross-examine his alleged victim, was in many ways a culmination of Lynch’s nightmarish experience with the court system since Simcox’s arrest.

In interviews with Hatewatch, Lynch has described feeling “left hung out to dry” by both the judge and the prosecutors in the case. She’s especially harsh in her assessment of the performance of the county’s victims’ rights advocates unit, which she says “has just not done their job.”

At one point, Lynch became furious with prosecutors when Simcox was offered a plea bargain that would let him out of prison after 10 years, in exchange for not forcing the girls to testify. However, Simcox himself dismissed the offer, and it was eventually taken off the table.

Lynch was also outraged at the way evidence was handled in the case, particularly the fact that Phoenix detectives failed to seized Simcox’s computer – the one on which he allegedly showed Lynch’s daughter pornography. Prosecutors reportedly explained it away by saying that he was only watching adult porn, a legal activity, on the computer, and so no search warrant for it was ever issued.

Lynch described feeling abandoned by the system. “Over the whole two-year process, victims’ rights in general have just not been followed,” she said. “I’ve gotten more information from reporters and television than I’ve even had with my own victim’s advocate. And I do all the reaching out to them, they never reach out to me.

“My daughter has only met her two times, for a maximum of two hours. So Padilla wants the victim’s advocate to be up on the stand with my daughter, but that’s a stranger too. So you want a stranger to sit with my daughter so that a man who has hurt her can question her. It doesn’t make any sense,” she said.

“You know, she’s not going to want to reach for somebody she doesn’t know, while somebody she does know who hurt her gets to talk to her.”

Lynch did, however, credit Phoenix New Times reporter Stephen Lemons with keeping her informed on the case, saying Lemons texted her with vital updates on the various court rulings and had apprised her of other developments in the trial as they occurred. At other times, she said, she was informed through the social media grapevine.

“I found out about Chris representing himself two weeks after it was filed and approved, through a television news picture that my boyfriend sent me,” she said. “I had a panic attack at work, because nobody had told me about it.

“I went on the county website and found that it was all there, but no one had given me a heads up,” she added. “I should have gotten a phone call the day that he filed to represent himself. I shouldn’t have to do all of that work. I shouldn’t have to become my own legal aide.”

The most difficult part, she says, has been helping her daughter – who gets counseling weekly – heal from her trauma.

“It’s definitely no fun,” she said. She described the recent upheaval in the case as especially trying, since her daughter had not yet been told that Simcox would be asking them questions.

Her daughter was shocked. “She was hysterical. She started crying. She didn’t want to talk to him, and she cried herself to sleep in the car. And then it was an hour later that the advocate texted me and said there was nothing going to happen on Thursday and the judge was going to wait until Monday. So after all that I had to go in and tell her it wasn’t going to happen.”

She is elated that Phoenix attorney Jack Wilenchik (who had been referred to her by Lemons) was able to stop the train wreck from happening, at least for now, by persuading Arizona Supreme Court Justice John Pelander that, in the words of his petition, “if the court allows the child victim to be subject to cross-examination by her abuser, then the victim’s constitutional right [under the Arizona Constitution] to be free from harassment and intimidation will be permanently violated.”

“It’s been really, really difficult,” Lynch said. “I honestly am pleased about the delay, because it’s about making sure that my daughter doesn’t suffer more trauma than what she has been going through.”