The last days of a Klansman: Edgar Ray Killen remained a defiant racist in prison until the end

Stubborn and willing to take up violence as a Ku Klux Klan kleagle in rural Mississippi, prison did nothing to mellow Edgar Ray Killen.

Killen received 17 disciplinary write-ups from the time he entered state prison in Mississippi in 2009 until his death in January at the age of 92.

His prison record, obtained from the Mississippi Department of Corrections via a public records request by the Southern Poverty Law Center, depicts an aging man who remained defiant and racist until his final days at the Mississippi State Penitentiary in Parchman.

The offenses ranged from hiding tobacco in the cushion of his wheelchair to calling a staff member a “black b----.”

Prison was quite the comedown for a man who remained free for four decades after orchestrating the killings of three civil rights workers in 1964 during what was known as “Freedom Summer.”

40 years a free man

As the civil rights movement heated up, Killen, a sawmill owner and Baptist preacher, worked as a recruiter for the Klan in Neshoba County, about 90 minutes east of Jackson. He was also a staunch segregationist — views he would hold his entire life. In the summer of 1964, civil rights workers descended on Mississippi to register black voters and show them how to exercise their rights at the ballot box after being effectively disenfranchised since 1890. Among the group that went to Philadelphia were 20-year-old Andrew Goodman of Ohio, 24-year-old Michael “Mickey” Schwerner of New York, and 21-year-old James Chaney from Meridian, Mississippi.

Killen would order the trio killed in an attempt to stop the voter registration drive and scare off any other civil rights workers from the area.

The local Klan deemed the three troublemakers and had them arrested and taken to the local jail. After the three were released and headed back to Meridian, Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner were stopped by patrol lights and two carloads of KKK members on Highway 19, then taken in Price's car to another remote rural road. The men approached then shot and killed Schwerner, then Goodman, and finally, after chain-whipping him, Chaney. They buried the young men in an earthen dam nearby.

The men's bodies remained undiscovered for 44 days in a case that touched off the “Mississippi Burning” investigation and later inspired a movie by the same name.

The federal government stepped in and prosecuted 18 people, including Killen, on charges of civil rights violations. Seven people were convicted and received relatively minor prison sentences. The jury hung on the charges against Killen, who walked out of the courthouse escaping any legal jeopardy or responsibility that day in 1967.

While free for 40 years after the killing of three civil rights workers in the central part of the state, Killen was powerful enough to avoid a retrial.

Killen bragged to the Clarion Ledger in Jackson, Mississippi, that he wouldn’t be prosecuted, claimed Goodman and Schwerner were “communists” and said he wanted to shake hands with the assassin of Martin Luther King, Jr. He even appeared at a booth at the Mississippi State Fair in 2004 for the racist Nationalist Movement.

Killen remained unencumbered by anything but his health and notoriety until 2005. That January, Mississippi prosecutors stepped in under pressure and charged Killen in the deaths of Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner.

Six months later, a jury would convict Killen of three counts of manslaughter, resulting in a trio of consecutive 20-year sentences. After losing his appeals, Killen reported to prison in 2007 and was transferred to the state system in 2008.

Hard time

Prison has a way of changing people.

Suddenly, the freedom to come and go, wear whatever clothes you like and eat whatever and whenever you want are gone. Life inside is extremely regimented, with corrections officers conducting head counts, mandating meal time and lights out and even controlling when someone can go to the prison commissary. Inmates either come into compliance with the strict lifestyle or find themselves repeatedly in trouble.

For Killen, who went to prison at age 80, the adjustment to not being in control appears to have been a tough one. Adding to the stress on an outspoken segregationist such as Killen was the fact that the bulk of the roughly 4,100 inmates — about 72 percent — at the penitentiary were black.

At Central Mississippi Correctional Facility in Pearl and the Mississippi State Penitentiary in Parchman, Killen had run-ins with prison officials almost from the start.

At the Central Mississippi facility on July 31, 2008, Killen got into a confrontation with a corrections officer and called her a “b----.” He also declined to sign the rules violation report, with an officer noting “Advised that he will not speak on it without the present of his lawyer.” It was one of multiple times Killen refused to sign off on a disciplinary report while in prison.

Killen lost 30 days of access to the inmate canteen for hiding tobacco products in the seat cushion of the wheelchair he used to get around the prison. It was one of at least three times such a punishment was imposed on Killen for defiance or rule breaking in prison.

Killen’s attitude and mouth appear to have caused him the biggest issues in prison.

While at the penitentiary on July 2, 2012, Killen began shouting at Corrections Officer Brenda Johnson: “B----, you need to get your boys to give me my damn tray. I saw you around there suckin’ on them.”

That outburst cost Killen 15 days of telephone privileges, a harsh bit of discipline in a place with few connections to the outside world.

Johnson also noted a “constant problem” with Killen on February 28, 2013, when Killen refused to put on a state-issued shirt before going to the inmate dining area. That also cost him 15 days of phone privileges. And, again, Killen refused to sign the rule violation report.

Killen lost all privileges — use of the canteen, phone and any visitation for 15 days — in April 2013 for another confrontation with Johnson, yelling at her: “You won’t let him (name redacted) give me my tray. I’m gonna get you! You black son of a b----!”

In a confrontation with a different officer on December 2, 2014, Killen told a corrections officer he was “going to beat my black ass and repeatedly called me a black b----.” That resulted in another 30-day loss of all privileges.

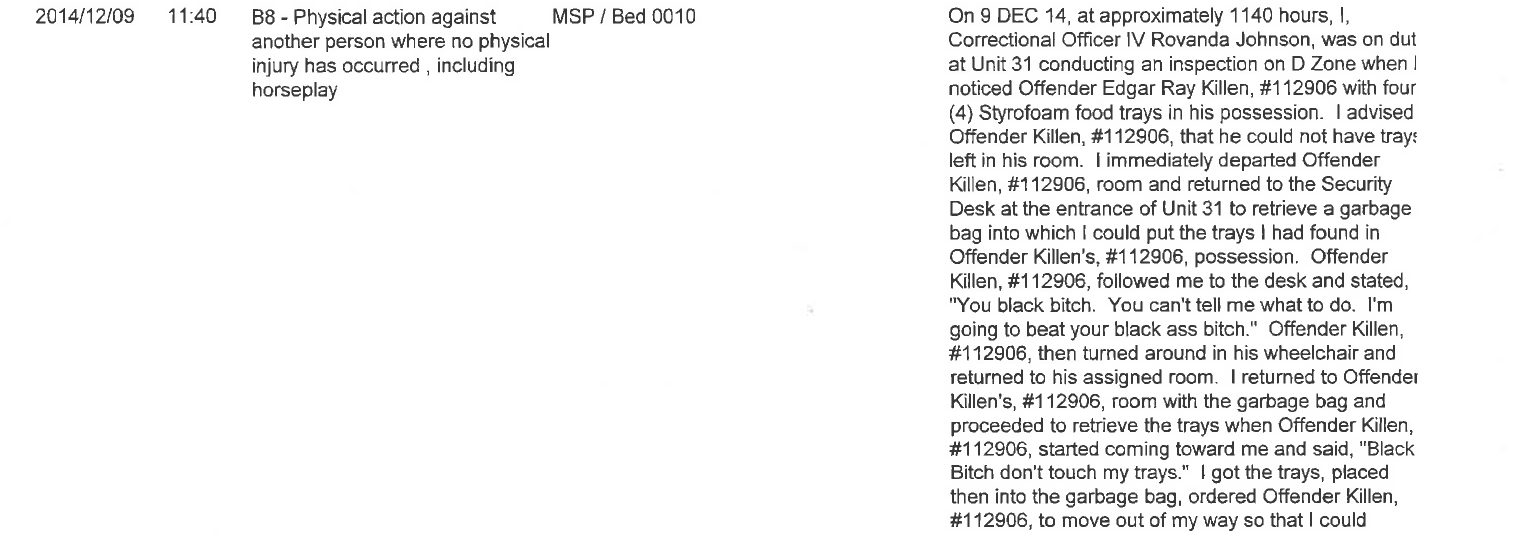

Killen’s most serious offense in prison, though, seven days later, when he confronted Corrections Officer Rovanda Johnson, who went into Killen’s cell to collect multiple food trays that should have been tossed out.

Killen followed Johnson to the security desk and told her: “You black b----. You can’t tell me what to do. I’m going to beat your black ass b----.”

When Johnson returned to Killen’s cell to collect the trays, Killen rolled toward her in the wheelchair and said, “Black b---- don’t touch my trays.” Killen then used the wheelchair to block Johnson’s exit from the cell before throwing a cup of coffee on her.

Killen then rolled toward Johnson and told her “You black b----. I told CID (criminal investigations division) that you are messing with my bed you black b----.”

Johnson then sprayed Killen’s face with a chemical agent, forcing him out of the doorway. Killen was later allowed to wash off the chemical agent but declined any other medical attention.

Around this time, Killen also reached out to several media outlets, publicly expressing the defiance he was showing in prison.

Killen told The Associated Press in 2014 that he wasn’t a criminal but a political prisoner.

"I could have beat that thing if I'd had the mental ability," Killen said.

Death of a Klansman

When the end came for Killen six days before his 93rd birthday, it was without fanfare, a fuss or even a whimper.

Corrections officer Devin Booker found Killen unresponsive in his cell just before 9 p.m. on January 11 during routine rounds. If other inmates heard any distress sounds or had any concerns about Killen, it isn’t noted in prison records.

Nurse practitioner Angela Brown pronounced Killen dead an hour later.

Killen’s funeral arrangements stayed largely out of the public eye, and only two people — both of whom said they never met the man — posted on his online condolence book.

Killen is buried in a family plot in Pine Grove Cemetery in House, Mississippi, about five minutes from where Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner were killed.