Media and legal treatment of ideologically-motivated violence by Muslims disproportionately higher than non-Muslims

American courts and media outlets treat individuals who are perceived as Muslim and accused of ideologically-motivated violence differently

That’s the key takeaway from an exploratory study released Thursday by the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU), a Washington, D.C., think-tank.

Entitled, “Equal Treatment? Measuring the Legal and Media Responses to Ideologically Motivated Violence in the United States,” the study was based on 2002 through 2015 data extracted from the Southern Poverty Law Center’s “Lone Wolf” report, University of Maryland START Center’s Global Terrorism Database and The Intercept’s “Trial and Terror” project.

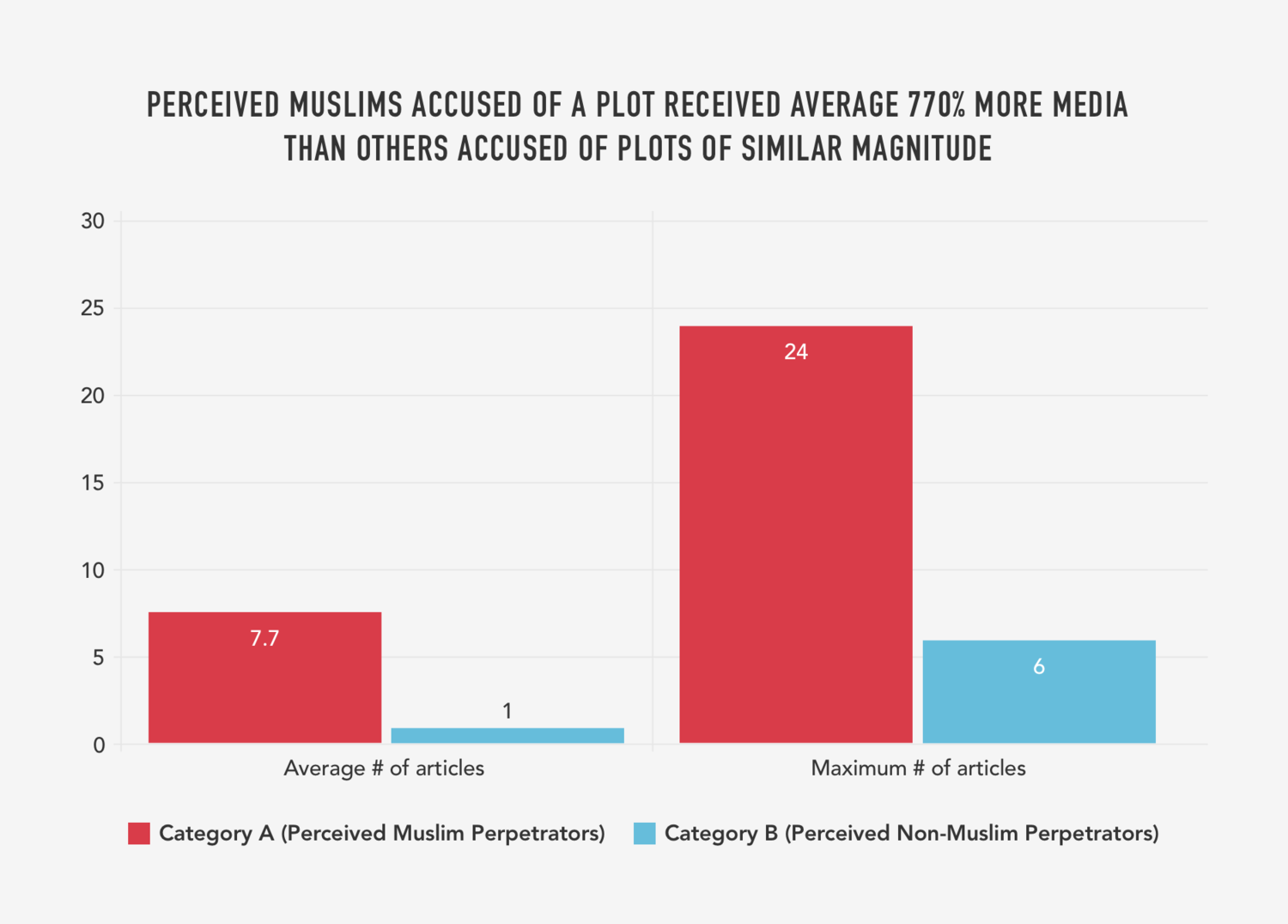

ISPU’s study found that media coverage of suspects perceived to be Muslim and accused of successfully carrying out a terrorist attack received on average more than twice the attention of their perceived non-Muslim counterparts. When it came to coverage of plots that were not carried out, perceived Muslim suspects were given 770 percent more media coverage.

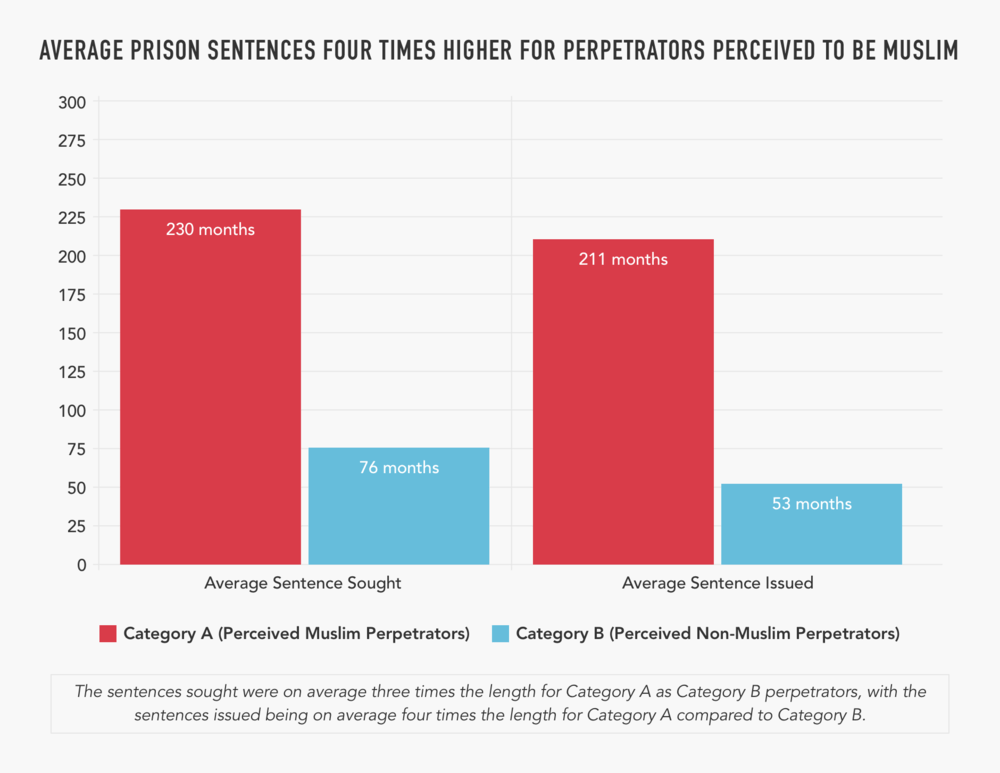

The report points to similar impacts upon legal processes and outcomes. According to its findings, suspects perceived to be Muslim were on average charged with sentences that were 302 percent longer than their perceived non-Muslim counterparts (230 months versus 76 months). The actual conviction outcomes revealed similar disparities: perceived Muslim suspects were given an average sentence of 398 percent longer than their perceived non-Muslim counterparts (211 months versus 53 months).

The authors’ use of the term “perceived” when describing suspects was a deliberate analytic decision, which refers to how law enforcement and media — not the ISPU researchers — described the backgrounds of the alleged perpetrators.

ISPU’s researchers examined five different factors across their data to create as much of an “apples to apples” comparison as possible between perceived Muslim and non-Muslim cases. These factors were the numbers of fatalities, the types of weapons used (e.g. explosives, firearms, etc.), intended outcome, target of incident and existence of any co-perpetrators.

On the whole, ISPU’s exploratory study represents a modest yet extremely important, evidence-based step toward a more informed conversation on public safety, bias and justice. Their study examined 52 randomly-selected cases of ideologically motivated violence between 2002 and 2015, based on coverage by The New York Times and Washington Post.

Its timespan does not include more recent high-profile incidents such as the ISIS-inspired 2016 shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida, and the 2017 white supremacist car-ramming attack in Charlottesville, Virginia, that killed Heather Heyer and wounded 19 others.

Still, their work builds upon the insights of other emerging scientific investigations, such as a forthcoming peer-reviewed study by a trio of researchers from the University of Alabama and Georgia State University who found that terrorist attacks by Muslim suspects “received, on average, 357% more coverage than other attacks” by non-Muslim suspects. That study also controlled for several factors including fatalities and attack targets.

In speaking to Hatewatch, study co-author Carey Shankman noted that “media and legal systems don’t operate in vacuums” and ISPU’s study is unique in the sense that it looks at both systems in tandem to each other, rather than separately.

Cognizant of the study’s exploratory and descriptive nature, the researchers declined to offer concrete policy recommendations.

For them, revealing the very existence of legal and media disparities when it comes to acts of ideologically motivated violence is an important first step toward advancing national conversations on public safety and equal justice under the law. “What we are pointing out is that when you have equal conduct, you expect there to be equal treatment,” Shankman said.

Since 9/11 government policy had explicitly prioritized combating movements claiming to act in the name of Islam. Even with intelligence assessments predicting the renewal of a violent U.S. far-right movement post-Obama election, policymakers continued to view Al-Qaeda and its associated actors “as the preeminent security threats to our country.” Policymakers took this position despite empirical evidence challenging the assumptions behind this premise, including frequency of plots and attacks, as well as ample evidence of far-right intent and capability to cause mass casualties.

The report’s findings come at a time when the far-right movement in the United States is robust and resurgent, and often resorts to violence. Policymakers and the public at large are debating the best way to effectively address various forms of ideologically motivated violence. In 2017, it was reported that the Trump administration had considered the idea of changing federal efforts from Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) to “Countering Islamic Extremism.” That same year, it also rescinded a CVE funding award to Life After Hate, a civic organization dedicated to helping individuals leave racist far-right groups.

[Full disclosure: This article’s author worked for ISPU in 2014 and reviewed a draft of the report.]