March for justice continues on anniversary of Voting Rights Act

Forty-eight years ago today, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 into law. The message was clear: The voices of minority voters would no longer be silenced at the polls. Though our country has made progress since 1965, the flood of controversial voting laws pushed by states in the wake of this decision only underscores the need for the Voting Rights Act.

Forty-eight years ago today, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 into law.

Discriminatory practices such as literacy tests were banned under the act’s extensive protections. Jurisdictions with a history of discrimination were required to get federal approval for any changes to elections. The message was clear: The voices of minority voters would no longer be silenced at the polls.

Sadly, the U.S. Supreme Court gutted a key provision of the Voting Rights Act earlier this year, opening the door to new forms of discrimination. The court, by a 5-4 decision, struck down the formula used to identify jurisdictions, such as Alabama and Texas, that must receive federal approval for any changes.

Though our country has made progress since 1965, the flood of controversial voting laws pushed by states in the wake of this decision only underscores the need for the Voting Rights Act.

After the high court’s decision, Texas officials wasted no time in moving forward with a strict voter ID law that a federal court had blocked because the law could disproportionately affect Latino and black voters. Alabama and Mississippi – also freed from the need for federal approval – said they had moved forward with new voting laws. In North Carolina, a state where several counties were covered by the act, the governor is set to sign a strict and controversial set of voting laws.

It seems as if Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was prophetic in her dissent, which noted that getting rid of the provision was like “throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

But even without states passing controversial laws, there is still a need for the Voting Rights Act. You need only to look at Alabama. Though the state is the birthplace of the civil rights movement, a black candidate has never defeated a white incumbent or won an open seat in a statewide race.

In majority-white local jurisdictions, black political success is still rare. Black officeholders in Alabama are confined almost exclusively to minority districts created as a result of lawsuits like the one the SPLC litigated in the early 1970s to ensure that black voters are not completely subsumed by majority white districts hostile to their interests. Clearly, the march for justice didn’t end in 1965 with the stroke of a presidential pen. It must continue.

The Voting Rights Act was earned through the hard work, blood and lives of civil rights activists. It was paid for with the lives of James Earl Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner – civil rights workers killed by Klansmen and buried in an earthen dam in Mississippi during Freedom Summer in 1964. It was paid for with the life of Viola Liuzzo, a Detroit mother of five who drove to Selma, Ala., to help civil rights marchers, only to be gunned down by Klansmen.

And it was paid for with the life of Jimmie Lee Jackson, a man beaten and shot by Alabama state troopers as he tried to protect his mother and grandfather from a trooper attack on civil rights marchers. His death would ultimately inspire the 1965 Selma-to-Montgomery voting rights march.

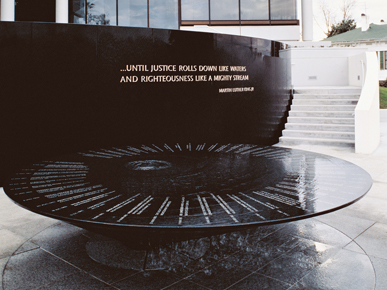

Their names and the names of other civil rights martyrs are etched in the black granite of the Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery, Ala. – a monument to those who made the ultimate sacrifice for equality and a reminder that we must continue the march by ensuring the promise of the Voting Rights Act is fulfilled.