Julian Bond remembered for unwavering devotion to equality for all

They came from across the country to remember one of the nation’s most eloquent and passionate voices for justice.

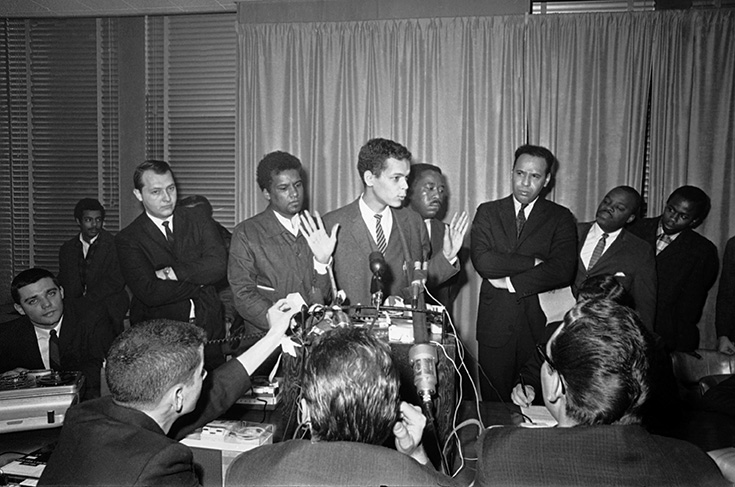

Civil rights activists, policymakers, scholars and friends numbering about 1,200 filled the historic Lincoln Theatre in Washington, D.C., today for a memorial service honoring civil rights leader Julian Bond, who died on Aug. 15 at the age of 75.

From a stage that hosted performances by Duke Ellington, Nat King Cole and Ella Fitzgerald, stories were shared, songs were sung and a life dedicated to the pursuit of justice was celebrated. Bond’s wife, Pam Horowitz, set the tone as she welcomed an audience that included President Obama’s senior adviser, Valerie Jarrett; House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, various members of Congress, author John Grisham and children of President Lyndon Johnson.

“Some of you may recall that whenever Julian was asked – by friend or stranger – how he was, he would always say, ‘Almost perfect.’ And to me he was almost perfect,” Horowitz said. “He was the greatest joy of my life. And I am so glad that he knew it. I hope today’s service will help lead us all away from the sorrow and back to the joy.”

Pulitzer Prize-winning author and civil rights historian Taylor Branch, who hosted the memorial, began the service by noting that Bond’s passing was marked by not one – but three – U.S. presidents offering their condolences to Horowitz. Presidents Obama, Clinton and Carter heralded his courage to ensure equality and freedom for all.

“Julian took up the righteous work of stirring consciences and opening hearts, and his example reminds us of the ability we each hold to move our Nation forward on our unending journey toward becoming a more perfect Union,” President Obama and first lady Michelle Obama said in a statement. “Your husband will live on in all those still fighting to secure equality in our time, and we will always feel privileged to be among those who called him a friend.”

SPLC founder Morris Dees was among those still fighting for equality who spoke at the memorial. He met Bond in 1971 – an encounter that resulted in Bond becoming the first president of the fledgling civil rights organization. In the wake of the civil rights movement, Bond recognized that the fight for equality wasn’t over. There was a need for groups such as the Alabama-based SPLC to ensure the promises won by the movement became a reality in the South.

“He knew it was going to take a lot of blood, sweat and tears,” Dees said in prepared remarks. “So, he told us that as long we agreed to keep our eyes on the prize and never give up, he’d agree to become our first president and stand with us for as long as it took. And that’s exactly what he did – from those early days to just a few months ago.”

Bond served as SPLC president from 1971 to 1979 and spent the rest of his life as a board member. He was an integral part of the SPLC’s success, serving as the narrator for the SPLC’s Oscar-winning documentary A Time for Justice, as well as the Academy Award-nominated Shadow of Hate. He recently served as a consultant on the SPLC’s latest film about voting rights in Selma.

Myrlie Evers-Williams, widow of slain civil rights activist Medgar Evers, recounted the support and friendship he offered over the years. When Evers-Williams completed her tenure as chair of the NAACP, Bond succeeded her in 1998, guiding the organization for 12 years.

“The NAACP had to have Julian Bond at the helm in order to move the organization forward,” she said. “I knew that he would stand on his well-honed principles to do what was right, that he would always defend the legacy of the NAACP, and that his actions would always speak ‘truth to power.’”

The last time she saw Bond was in 2014 at an Oprah Winfrey event celebrating the opening of the movie Selma. Evers-Williams recalled how he sat quietly in the audience, smiling at the young people who seemed in awe of him.

“He knew his wisdom – he didn’t have to posture,” she said. “So many young people followed him like the pied piper. His teaching has left an invaluable imprint on everyone. I will always remember Julian for his strength, his endurance, his loyalty and his friendship. I will miss his words. I will miss his presence.”

‘Not your typical politician’

He carried those traits with him as a candidate for the Georgia legislature. Judy Richardson, a civil rights activist and filmmaker, recalled watching him meet with a group of elderly African-American women during his campaign in the 1960s. It was obvious from their faces that they were pleased with his intellect and demeanor. But there was something else that stood out to them, a skill cultivated as founder of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

“It was when he began talking that they understood he was not your typical politician,” Richardson said. “Because Julian didn’t tell them about his platform – he asked what they wanted him to include in that platform – this was a SNCC campaign. … And so the women talked about the things – big and small – that they wanted for themselves and for their families. And Julian listened.”

When Bond was elected to the legislature in 1965 but denied his seat because of his opposition to the Vietnam War, he demonstrated the strength and integrity necessary to take his case to the U.S. Supreme Court and prevail.

“He showed the kind of principled stand that he never, ever gave up for anything or anyone,” Richardson said.

An icon, a father

Bond’s son Michael also reflected on his father’s work – memories of the activist typing speeches late at night as The Tonight Show played in the background, phone calls with community leaders and his work at the Georgia capitol – but there was another side to the civil rights icon, his role as a father to five children.

There were the Saturday nights spent with his father watching TV and eating pizza, visits to the state capitol and the memories of his father’s love of music, which filled the home with the sounds of Ray Charles, The Coasters, The Ink Spots and other renowned musicians.

Though the public may have seen Julian Bond as an icon, his children saw him in simpler – and dearer – terms.

“For us though, he remains simply ‘daddy,’” he said.

Bond’s love of music also was evident throughout the service. It began with Grammy-winning jazz trumpeter Scotty Barnhart leading two choirs into the theater to perform “Oh, Freedom,” which was played at the 1963 March on Washington. As the chorus performed underneath a photo of a young Julian Bond, the audience rose to its feet and sang along.

The group followed up with a rendition of “This Little Light of Mine.” The Freedom Singers, a group formed in the 1960s to educate people about civil rights, also performed during the service to rousing cheers.

The power of music was highlighted by Branch. He recounted how he was struck by “It’s a Blue World,” a signature song by The Four Freshmen, one of Bond’s favorite groups. “It’s a blue world without you now, Julian, but we know that music can build courage and heal regret,” he said. “Music’s language of emotion moves people, which can sustain movements built on great ideas.”

Eyes on the prize, eyes on the future

The memorial also made clear that Bond’s pursuit of justice did not wane. In recent years, he turned his attention to LGBT rights, becoming a vocal crusader for equality. On the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington, he used the occasion to declare that LGBT rights are human rights.

“Julian’s legacy was cemented long before he decided to speak out on issues of importance to LGBT Americans,” said Chad Griffin, Human Rights Campaign president. “He didn't have to fight for LGBT equality. But in doing so he became our greatest champion.”

Bond also recognized the importance and power of the next generation. During his lifetime, he taught about the civil rights movement at several colleges and universities. In his classroom, he focused on the unsung heroes of the movement, noting that it relied “not on the famous but the faceless” – a lesson with the power to inspire future activists, said Daniel Gutman, who was a student of Bond’s at American University in Washington, D.C. and served as an SPLC legal intern.

“Professor Bond taught us that if we are brave enough, if we are committed enough, we might just make history ourselves,” Gutman said. “None of us, of course, will probably change the course of human events in the way that Julian has done. But because we had the great privilege of being in his class, I know that all of us feel compelled to try.”

As the memorial neared its conclusion, Heather Booth, director of the NAACP National Voter Fund in 2000, offered words for the audience to remember.

“We honor Julian not just by what we say here today but what we do tomorrow and the next day, and the next day as we keep his spirit in our hearts and work relentlessly to make real his vision of equal rights for all,” she said eliciting cheers of “Yes! Yes!” from the crowd. “He would want us to remember what he fought for. But more importantly, he would want us to continue to actively support the many struggles to which he dedicated his life.”

Music filled the theater for a final time as the Choral Arts Society of Washington and others performed “May the Circle be Unbroken” as the audience stood and applauded. As the last note faded, it was clear that the service was at its end, but not the march for justice to which Bond devoted his life.

The memorial was overseen by Bonnie Nelson Schwartz, a theatrical producer and close friend of Pam Horowitz and Julian Bond. “It was Bonnie’s loving expertise that made it so beautiful, and I will be forever grateful to her,” Horowitz said.