Growing up as a child of the Little Rock Nine

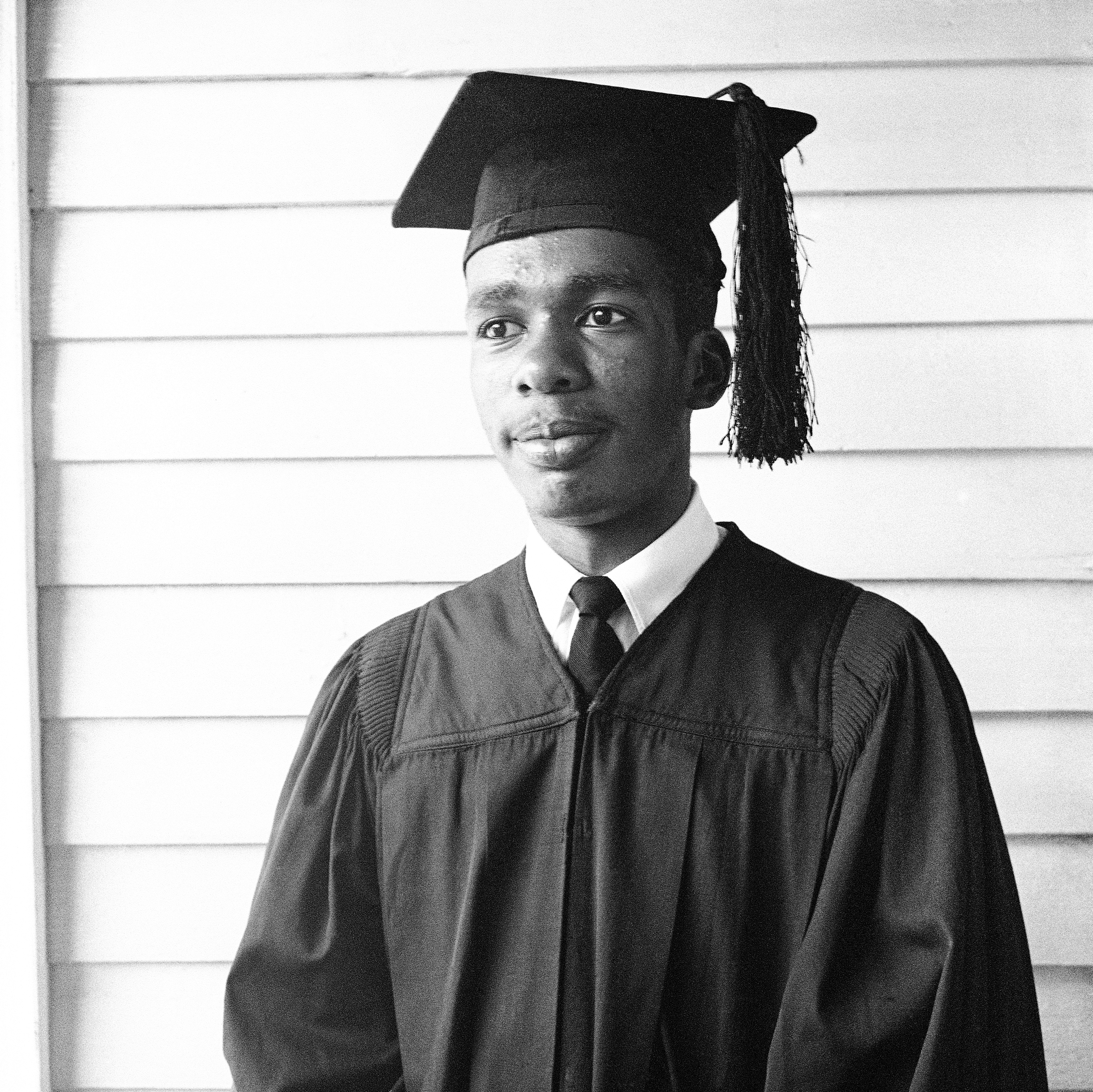

On May 27, 1958, Ernest Green became the first black student to graduate from Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas. He was among the group of black teens — known as the Little Rock Nine — who had integrated the school in 1957.

Sixty years later, we sat down with Green and his daughter, MacKenzie Green, to talk about graduation, Hollywood, and activism today. We conducted the interviews separately but asked them the same questions. Their responses have been edited and condensed, and are presented together.

MacKenzie, what is it like being the child of one of the Little Rock Nine?

MacKenzie Green: It’s funny because it’s not pressure from him; it’s pressure from me once I figured out who he was. Because it’s not like I grew up with him being like, “I’m Ernest Green, capital E, capital G,” no, it was — he was dad.

Ernest Green: She’s absorbed this legacy and the history, and she wanted to be her own person. That’s kind of where I started out. I wanted to be my own person. I believed that [Little Rock] Central High at the time offered the best alternative for me, and I couldn’t figure out why I wasn’t there.

Ernest, how did you end up attending Little Rock Central High School?

EG: This was three years after the Brown [v. Board of Education] decision. The Little Rock school board was under a court order to desegregate in 1957, and spring of ‘57 I decided that I wanted to transfer. I didn’t pay a lot of attention to the process. All I did was to sign a piece of paper that I was willing to be a transfer student. I lived in the Central district, and I sort of left it at that

What did your parents think?

EG: My dad had passed, and my mother and my aunt were both schoolteachers. My grandfather was a retired letter carrier. I’m certain they had reservations about my going there, but they never imposed that on my decision. They said they would support me as much as I needed support, and that they were standing behind me. They didn’t think I was making a wrongheaded decision, but I’m certain they took some negative responses from people in the community, because everybody in the black community wasn’t sold that this was something they wanted to support.

What kind of pushback did you receive?

EG: I had a job for the summer as a locker room attendant at the country club. Some time during the middle of the summer, the school board published the names of the students who were eligible to transfer, and I suspect that they did that to try to intimidate and whittle down the numbers. Of course, that’s what occurred. But while I was working at the country club, I had developed a friendship with one of the members’ sons who was about my age. The day they published my name in the paper, he came screaming into the locker room, very upset, agitated, wanted to know how I could do that. “You seemed like such a nice guy!” So that gave me some indication that this was not going to be a day at the beach, but we clearly didn’t anticipate that they were going to call out troops to bar our entrance.

What has it been like watching MacKenzie get an education in a system very different from the one you integrated?

EG: It’s what I thought we were fighting to change.

MG: I just finished my MBA at Columbia, and I remember the last day of orientation fell on the same day as the first day that he got to [Little Rock] Central High. I remember sitting there with one of my classmates and saying, you know, “This is kind of heavy.” I said, “I am starting at this Ivy League institution that didn’t take people who looked like me, and getting a degree that most people that look like me still don’t get.”

EG: It’s rewarding to see that they don’t have to go through the same hassle that I had at their age. That’s the outcome we wanted to see occur.

MG: It was a weird time to drop into Columbia, though, because you had the beginning of Black Lives Matter, and then the [2016] election. Sometimes, my peers would look at me for a perfect answer, or to be stressed or outraged. I was actually having a fight with a classmate recently, who was like, “I’m so stressed!” And I said, “That’s not a choice. That’s a state of paralysis that I can’t be in with you.”

MacKenzie, what’s next now that you’ve graduated from Columbia?

MG: I looked around and said, “Where are there no black people. Where are there no women?” And I thought, “Oh my God, Hollywood!” It’s entertainment, it’s this world where there’s another glass ceiling — in my case a stained glass ceiling — to be broken. Sometimes he’ll look at me and say, “You know you don’t have to be the first at something. You know you can just find something you like,” and I’m like, “Well I know you say that,” and I go, “But for me, I’ll feel disappointed if you did all of this, and then people are like, ‘Well what became of his daughter?’ and they’re like, ‘I heard she’s a really great soulcycle instructor!’”

EG: MacKenzie has a lot to say. She really knows the subject matter and I’m proud of what she’s achieved.

MG: During my time at Columbia, I interned at a bunch of different entertainment brands, Harper’s Bazaar, Paramount Pictures, NBC Universal, so eventually my dream of all dreams is to be the chief marketing officer of a Hollywood studio. I just think there’s something very poetic and beautiful about an industry that was built on “Birth of a Nation” eventually having somebody sitting there looking like the faces that they said were going to destroy the business.

EG: She has the vision, she has the energy, and I think she has the intelligence that she can achieve that.

MG: Actually one of his gifts to me when I got the Paramount gig was a “Birth of a Nation” vintage poster. He was like, “When you’re ready we’ll get it framed, and put it up in your office right next to your Columbia MBA.”

EG: I think she’s the kind of person that needs to be there.

Ernest, what was it like watching MacKenzie graduate from Columbia?

EG: She’s a lady with a mission. She’s staying on point and trying to complete the things she wants to do.

MG: There is no finish line to this. My dad taught me that the first one through the wall is the bloodiest.

EG: I’m sure there’s somebody right now in Little Rock who thinks that we brought down the bubonic plague, we nine, but all you can do is just continue to push.

What was your graduation from Little Rock Central High School like?

EG: Principal Matthews told me I didn’t have to attend the ceremony, that they would mail me my diploma. I thought about that for about half a millisecond. I didn’t go through all this not to participate in it. The night of the ceremony, they called out all the students who had received awards and scholarships, and I had received a scholarship from Michigan State. They didn’t cite me.

MG: I was talking about this with my dad today, and he said, “I went to my 50th high school reunion” — not the anniversary of the Little Rock Nine [integrating the high school], but his actual senior high school reunion — and he said, “There was not a single person who was at that 50th reunion who did not think me going to Little Rock was the greatest thing that ever happened. They were so happy I was there, everybody was apparently my friend.” And he says, “That’s the funny thing about right now,” he goes, “Yes, there’s divisiveness, there is fighting, there are these moments of complete and total chaos, but I can guarantee you when, God willing, we have the 60th anniversary of the Colin Kaepernick kneel, people will be sitting around and saying, “I’ve always thought it was the greatest idea ever. I just thought it was so brave.”

EG: I think there’s no reason to let up, and not continue to push.

Especially when Martin Luther King Jr. personally attended your high school graduation.

EG: Unbeknownst to me, Dr. King was speaking at Pine Bluff, Arkansas, which is 35, 40 miles from Little Rock, and he wanted to come up and witness my graduation. He was close to Mrs. Bates, who was the head of the NAACP. This was the beginning of his career, so it’s almost impossible for anybody of this generation to believe anybody didn’t know who Dr. King was, but in fact I’ve always said if local police had known who he was they probably wouldn’t have allowed him into the ceremony. Anyway, he sat with my mother and aunt and grandfather. Afterwards, we had a chance to get together briefly. I had a party at the house and after we said our hellos and all that. I’m a 16-year-old teenager that just graduated from high school, so I was more interested in hanging out with my friends.

MG: But you know, he didn’t stop. He got to Lehman Brothers and looked at young black men who were coming in, and people would say, “I don’t think he has the potential,” and he’d say, “I see potential. I’m willing to take him on.”

EG: I feel really recognized that Martin Luther King attended my high school graduation. My mother kept a diary of gifts and things I received, and in that diary is a notation of M.L. King of Montgomery, Alabama. He wrote a check for $15. I’m pretty certain I’m in very rare company there.

Ernest, how did you juggle carrying on a civil rights legacy with raising small children?

EG: We really didn’t start getting this kind of recognition until the 25th or 30th anniversary.

MG: It didn’t seem strange to me that my father had to travel a lot during February, or that sometimes when I picked up the phone and said hello, it’d be like, “This is a call from the White House,” and I’d be like “Dad, it’s for you!” These things felt normal because he created a sense of normalcy. And yet he was on a plane traveling the world! But he traveled with my storybooks, and read them to me every night.

EG: Partly you’ve got duties as a parent, so some of that doesn’t interfere with the weight of history. But I’ve always said that I’m the oldest show-and-tell for each of my kids, from kindergarten through to graduate school. So I’ve gotten used to it.

MG: I remember I didn’t know he’d been at Nelson Mandela’s inauguration, but he got home on a redeye, slept in the living room in his suit, woke me up the next morning to go to swim practice, and sat through the entirety of practice at 6 o’clock in the morning. He never said like, “Oh, honey, mom’s gonna have to take you to swim practice, I’m so tired, I was at Nelson Mandela’s inauguration.” It’s like, “She’s 8! She doesn’t know or care about any of this, this isn’t what she’s going to remember.”

EG: We attended a lot of swim practices. But if she was willing to work that hard at it, there’s no reason I couldn’t get up and get her to events and practices and meets. I’ve been to more horse shows and swim meets than any other American I think.

MG: I’m very good friends with Andy Young’s granddaughter — she and I grew up together — and we used to always tell our peers, “Our parents are alive, as are your parents and your grandparents, and they had an opinion on my father and her grandfather.” And I think now is that time when history is being created where I’m like, “You’re picking the stories you’re either going choose to omit to your grandchildren, or the stories you’re going to be proud to tell.”

EG: I call it the microwave generation, in which you put something in and it pops out in ten seconds. That’s not the case here.

MG: I think the interesting thing is how the trials of now have created a potential for the next generation of great thought leaders and activists to step into their own.

EG: I always saw it as a very long-term situation. If those who had some opportunity to influence the opinions of other students [at Little Rock Central High] had spoken up a little more, it probably wouldn’t have been as tough a year for us as it turned out to be. I think we’re going to experience this for some while, that the pioneers are the ones who have to create the road and the path and all that.

MG: That’s what I would hope to impart to my children: that the first step towards change is not easy, but you create an opportunity busting through that wall for others to come behind you.

EG: [MacKenzie] understands the importance of it. I’m going to be a supporter of hers to the very end.