'Why not my son?' How Sonnie Hereford IV and his dad integrated Alabama's public schools

It took Sonnie Hereford IV more than one try. Or perhaps it’s more accurate to say it took more than one try for Dr. Sonnie Hereford III.

On September 3, 1963 – the first day of first grade – the pair were greeted at Fifth Avenue Elementary School in Huntsville, Alabama, not by a friendly teacher or PTA welcoming committee, but by white parents chanting segregationist slogans, their children in tow.

“There was a mob out there, I guess 150, 175 parents and kids,” Dr. Hereford told AL.com in a 2013 interview. “They called my son and me everything you can think of.”

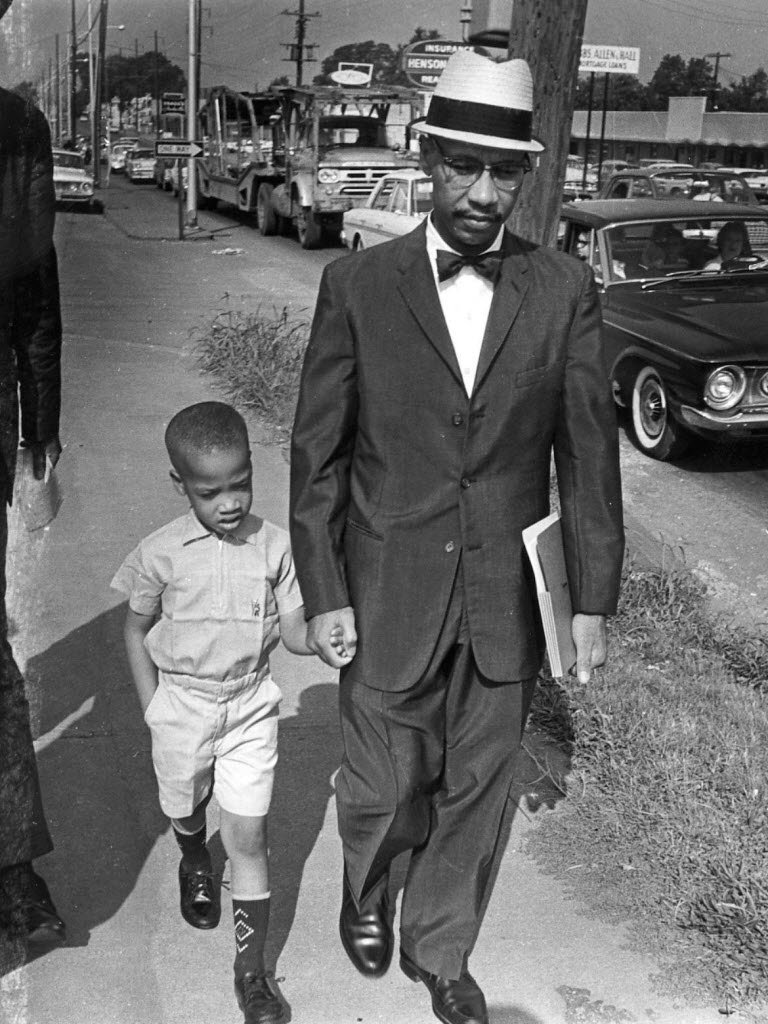

It was clear that Sonnie Hereford IV, who was just 6, wouldn’t get to start school that morning. They walked home, the father holding his son’s hand.

They tried again the next day, but Fifth Avenue Elementary School was still locked. When Dr. Hereford found it shut the day after that, too, he sent a telegram to the federal judge who had ordered the Huntsville Board of Education to desegregate the city’s public schools by enrolling his son.

At first, the telegram seemed to have backfired. The Herefords found the school surrounded by armed and helmeted state troopers, dispatched by Alabama Gov. George Wallace – who earlier that year had pledged “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!” – to prevent children of any race from entering the school.

But on September 9, 1963 – 55 years ago – Alabama could no longer keep Sonnie Hereford IV from first grade. He became the first black child to integrate public schools in the state.

In 2018, Hereford IV still bears a striking resemblance to the tiny boy in an iconic black-and-white photo who is holding his father’s hand as he climbs the steps to an elementary school whose doors had finally been opened to him. We sat down with him to discuss what he remembers of that day — and the many, many days it took him and his father to reach it.

On trying to enter Fifth Avenue Elementary School

Dad said that when he and I walked to school on those few mornings before I got to enter the school, he had been told that the Klan may have been in the vehicles in the traffic. He was told that after the fact. But he said many times that that would not have changed his mind, that he would have gone through with it.

He was just a brave person. He was going to make things better than they had been for himself.

On his father’s education

My dad's home was seven miles away from the school he had to go to. He and his brother and the other black children were not allowed to ride the school bus, even though there were buses that ran along the route, and even though black families had to pay taxes. The bus would come by as the black children were walking to school, and Dad said in the hot months, the dry times, it would kick dust up in their faces.

Worse than that, the white children on the buses would yell names out the window, or throw things, or spit. Dad said that the bus driver would even slow down as they approached, I guess so they could get a better aim.

At his school, the only school for black children in Huntsville, they had no gymnasium, no library, no science equipment to speak of. My dad knew he wanted to be a doctor, even as a youngster, and he knew he would have to know chemistry – so he had to order his own chemistry set.

He was determined his children would not have to put up with that.

On his father’s decision to put his son in public school

My father was a member of an organization in Huntsville working for civil rights, and in 1962 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. came here, to Huntsville. One of the things Dr. King said was that we need to get the schools integrated. If you can get the children at a young age going to school together, then they will see that people are just people. And Daddy said he thought, “Well, I have a son that’s about to start first grade, and if I’m going to be pushing for school integration, why not my own son?”

On threats

My parents protected me from a lot of the potential ugliness. For example, as the day approached for school to start, we were getting phone calls, death threats, to the house. My parents would not let me answer the phone, even though I was perfectly capable: They didn’t want me to answer the phone and hear that ugliness.

Dad would answer the phone and he would say something like, “Officer Tempson, Huntsville Police Department.” And then if it was somebody who knew us, they knew what the deal was, and they would continue the conversation.

But a lot of times what he would hear was click, because he would scare away the people who were calling to make some kind of a threat.

On discrimination at school

My parents protected me to the degree that I didn’t go in there looking for a fight, or worried that there was going to be a problem. And yet I understood my role. I understood I was representing more than just myself. Kind of like Jackie Robinson: It wasn’t good enough for him to be a good ball player, and it wasn’t good enough for me just to be a good student. I’m not sure my parents ever even told me this, when I got called names I knew that I had to sometimes bite my lip and take it.

I don’t remember many incidents of being treated differently at Fifth Avenue School, but I did get into one fight that I can recall on the playground. There was a young man out there, Roger – I still remember his first name – who was calling me names, but he didn't get me upset until he threw some dirt on me. That’s when we got into a scuffle.

The lady who was monitoring the playground dragged us into the principal’s office and I told the story: He was calling me names, he threw dirt on me; that’s when I sat on top of him and just put handfuls of dirt all over him. Roger didn’t dispute anything that I said, but I was the one who got in trouble for that incident.

On Confederate symbols at school

High school was difficult at times. There were racial problems, and part of that was because we were the Butler Rebels. We had a huge Confederate flag painted to completely cover the wall at one end of the gymnasium. Huge Confederate flag. The band would play Dixie at the pep rallies, and at the football games, some of the students would bring Confederate flags to wave. Every time we scored a touchdown the band would play Dixie, you know, to those touchdowns.

There were at least two riots on campus when the band started to play Dixie. This was the early to mid-’70s, because I graduated from Butler in ‘75.

Now, late in my junior year, I was president-elect of the student body. During that summer, I went to the school board and suggested that Confederate insignia and regalia should not be permitted on school property. Sure enough, the school board passed a rule. The Confederate flag got painted over in our gym. They were not allowed to have Confederate flags or play Dixie on school property, including the two football stadiums.

It’s taken a long time, but I think that people are getting it. Even when I was at Butler, I used to talk to some of my fellow students who were in favor of the Confederate flag and they would tell me, “But that’s our tradition. That’s our heritage.” And I would say, “That goes back to a segregated heritage. Why can’t we have something that everybody can rally around? Why should I be any less of an enthusiastic student and fan than you are?”

On racism today

My father said, “Back then, people used to spit on me and throw things at me and call me names.” He said, “Now they name schools after me.” I think that just says that society has made some progress, because there was a time when being racist was beyond accepted – it was almost expected, certainly allowed.

I think that at least we’ve seen a shift in the formal policies. But I think that there are still some issues; maybe it’s shifted a little bit from race to class. I think the people who are so inclined [toward racism] have been encouraged that they can come out now, and that they’ve got some support now.

When you saw the weak response to what happened in Charlottesville, I think people who were marching, the neo-Nazis and so forth, they feel like, well, he’s our man, he’s not going to come down that hard on us, and so all of these things that maybe people had to keep under the surface, I think that they’re more emboldened now.

I would not say that the present administration is responsible for it, but I think he tolerates it.

On the school named after his father

I remember dad saying that other than the day that he was married and the birth of his children, the [unveiling of Sonnie Hereford III Elementary School] was the proudest day of his life.

I think a lot of my personality is forged from that, from trying to be like him. I know that the consent decree that Huntsville is working under right now has my name on the upper left-hand corner of it.

I hope that [students there] appreciate the opportunities they have. I hope they make the most of them. One of the things I did here was I was part of a tutoring program. They discontinued that program, but there’s talk that they may start it [again] and I’ll be the first one to sign up. I just hope that they appreciate this facility, this equipment, this environment and these teachers – I hope they’ll go just as far as they can go.