Integrating Ole Miss: 'An assault on white supremacy worldwide'

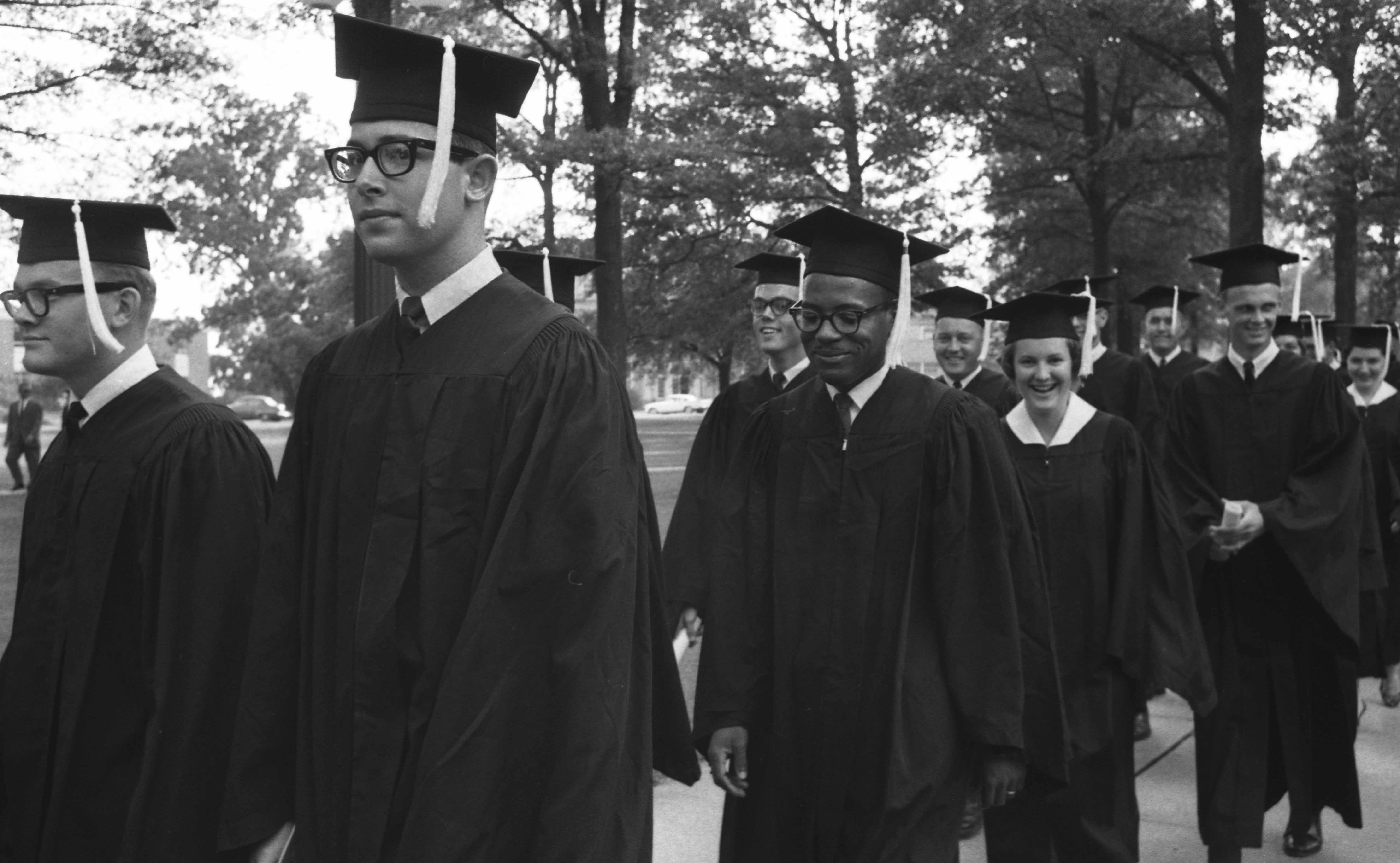

Fifty-six years ago — on Oct. 1, 1962 — James Meredith became the first black student to attend the University of Mississippi.

It took a Supreme Court ruling and 30,000 U.S. troops to get him to class. White supremacist riots on campus left two people dead and more than 300 injured.

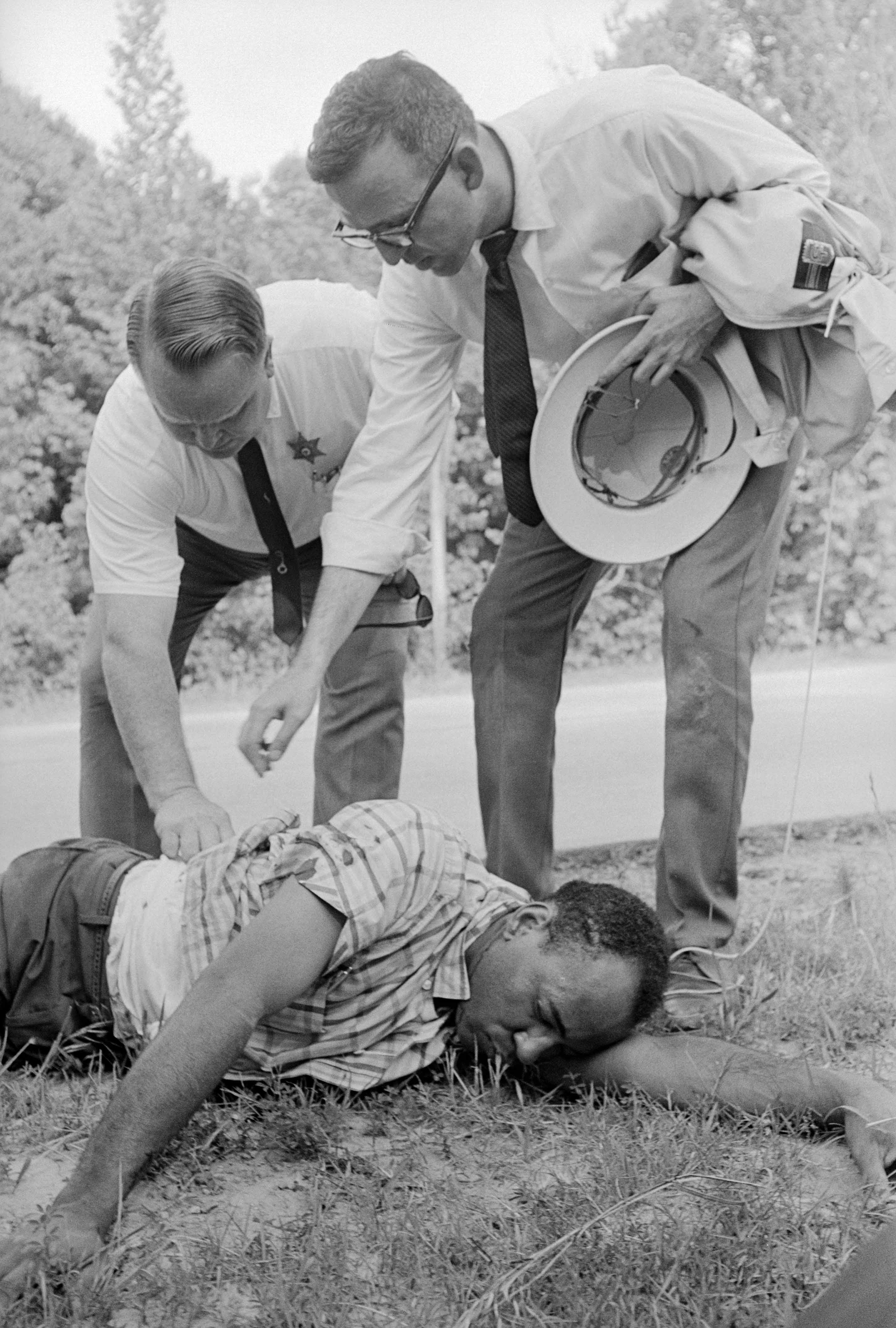

Four years later, Meredith planned a solo “March Against Fear” from Memphis to Jackson, Mississippi, to encourage voter registration and highlight continuing racial inequality following the Voting Rights Act of 1965. He was shot and wounded by a white man on the second day, but civil right activists — 15,000 strong at one point — completed the march.

Earlier this year, Meredith, 85, spoke at Calhoun Community College in Alabama. His remarks are excerpted here, alongside comments from an interview we conducted with his son, John Meredith, at his home in Huntsville, Alabama.

On integrating the University of Mississippi

James Meredith: You gotta understand Ole Miss was strictly a strategy and an assault on white supremacy worldwide. At age 4, I wanted to change what I saw every day of my life. I didn’t want to live in that circumstance. And that never left me, at all. I always wanted to do what anybody else couldn’t do or was scared to do. Mississippi even today has the reputation of being the worst in lynching and the worst in terms of every other thing than any other state. I was pretty smart, I knew what all that stuff meant, and I knew if I attacked Mississippi, even if I didn’t win it would make an impact. And I think I kicked Mississippi’s butt.

John Meredith: Ole Miss wasn't a matter of a person of color wanting to go to an integrated school. It was a citizen of the state, who paid all the taxes and fulfilled all the responsibilities required of them as a citizen, to go to the state, tax-dollar supported institution that they wanted to. That's a citizen's right. Had nothing to do with his color. He's a taxpayer and a citizen that did everything that the government told him he needed to do in order to be a citizen in good standing. And why should he be told he cannot even apply to the school supported by his tax dollars? So it wasn't a civil rights issue. It was a citizenship issue.

On the statue of James Meredith the University of Mississippi erected

James: They’re promoting it now all over the world. But when they put it up, I said, “It’s a false idol, take it down. If you really want to do something, take down the James Meredith statue in the back of the Lyceum, the main building on campus, take down the Confederate statue they got at the front end, and we’ll do away with that black-white race thing in Mississippi.” They said “Oh no.” They said, “We didn’t put that up to honor you! We put that up to appease these blacks who are here now because we can’t not have that here now.” So whenever they have a problem they go out there and look at that statue. As a matter of fact, for one whole year one black student sat out there every day. Rain, sleet, and that proved a point that this administrator told me, “We’re not doing this for you, James Meredith, and we ain’t gonna take it down.”

John: You have your [Confederate] monuments, OK. Where are the black monuments? Where are the monuments to Crispus Attucks? Where are the monuments to Booker T. Washington?

On working for civil rights as an individual

James: I was an individualist because I wanted to influence and change the life of every black and white in America.

John: He, in his whole life, has been about an individual citizen, what an individual citizen can do. His thought process was to say you shouldn't be afraid, that an individual, one person, should not be afraid to walk down to his county courthouse and register to vote.

On the March Against Fear

James: The most important thing I’ve ever done was the March Against Fear. Fear was and still remains the biggest factor in the manipulation and control of human beings. My daddy knew that all my life, and I knew it. Because we knew that was the thing that kept blacks from doing what they were entitled to do: the fear of being not just lynched but losing their home, losing their property, losing their job. Fear is a powerful force. So actually the March Against Fear, of which Dr. King did most of the leading, because I was lucky enough to get shot and not get killed — I walked 22 miles, he walked 200 miles — that just shows how good God is, how lucky I’ve been in my life.

John: When my father went to Ole Miss, he came back. When my father went to lead the march from Memphis to Jackson, he came back but he came back shot. People may not like you getting an education but they will kill you for trying to participate in government. So that's why it's more significant to me.

On the fight for civil rights today

John: Things have changed, but not as much as you think. Since 2016, with the uptick of hate groups and the like, we have regressed. And the January, February after [Obama] was inaugurated was at the time the most divisive I've ever seen the American public act, and this includes the '60s. You had John Lewis spit on by a white Tea Party person wearing all the paraphernalia as he was going to cast a vote [in] Congress.

James: Mississippi been at the bottom. Mississippi [is the] only state that hasn’t had a 2 percent raise in population in 100 years. But they want to change the image of Mississippi. So Mississippi has decided they [are] gonna have a cutoff point. The cutoff [is] gonna be in 1964, when the three civil rights workers was killed in Neshoba County, Mississippi. That’s the civil rights era. So there’s gonna be a Mississippi before the civil rights era and a Mississippi after.

On growing up with a civil rights icon for a father

John: Long term, it was a lot of pressure internally, on myself, that I had to succeed, that I could not fail, and it kind of haunts me to this day. The last thing you want to do is fail because you might wind up in the newspaper, you know: James Meredith's son got in trouble. Boom. On the news. But when I was growing up, the Saturday, the weekend father was not who everybody else knew, the public James Meredith. The father I knew was a guy that took me to Yankee Stadium. He's the guy that woke me up out of a sound sleep, way too early, to go have breakfast, just me and him, talk about whatever we wanted to talk about. Used to love just taking a ride with dad. That's the dad I know. That's the guy I think about when I close my eyes.

On carrying on James Meredith’s legacy

John: I guess [it] kicked in [when] I resigned from the hospital, went back to school and moved to Washington. He was proud before, but at that point, he actually expressed some pride, actually verbalized his happiness that I had gotten involved in politics. Hispanics, unfortunately, now are the ethnicity that is getting true hatred: they want to deport them, they want them locked up, split the families apart. They're detaining women and taking their children hundreds of miles away and detaining them somewhere else. That, that is a regression. People are hurting more now than they were 15 years ago. So let's acknowledge that. Let's try to do something about it.