Naming the enslaved, reconciling the past in Memphis

The roll call was solemn.

The words seemed to rise toward the vaulted ceiling of Calvary Episcopal Church in downtown Memphis.

Gerry, age 35.

Charles, age 48.

Dick, age 14.

They were African Americans sold at a slave yard owned by Nathan Bedford Forrest, who would go on to become a notorious cavalry commander in the Confederate Army and, in defeat, a leader of the Ku Klux Klan.

But the names weren’t just part of a history lesson far removed from the crowd that filled the church. In fact, the church’s parking lot covered the site of a large slave yard operated by Forrest.

Until this day, few people knew anything about it. No one had put up an historical marker recounting the site’s tragic history or Forrest’s role in it. There was, however, a conspicuous marker just 20 yards away to commemorate the site of “Forrest’s early home.” It proclaims that “his business enterprises made him wealthy,” neglecting to mention exactly what those “enterprises” entailed.

Last April, a more complete story was finally presented.

More than 600 people gathered for the unveiling of a new historical marker – one remarkably different than thousands of others that denote all things Confederate across the Southern landscape. This one notes that after the Civil War, “many white southerners chose to portray Forrest as a military hero, thus excusing or ignoring Forrest’s buying and selling of human beings.”

The installation – a project involving the church, nearby Rhodes College and the National Park Service – was part of a broader reckoning that’s taking place across the South.

Communities like Memphis are coming to grips with the growing recognition that Confederate monuments and symbols have long played a role in mythologizing the “Lost Cause” and glorifying the soldiers and generals, like Forrest, who fought to defend slavery and white supremacy.

“We’re in a remarkable period of American history right now,” said Tim Good, a superintendent with the National Park Service. “We have seen some very honest discussions concerning Confederate statuary and other symbols that have been erected as a result of the Civil War and, also, of white supremacy.

“Slavery continues to be a topic which receives less attention in regards to actual places that interpret it, and openly interpret it.”

Monuments and generals

As the SPLC has documented, across the country there are more than 1,700 symbols that honor the Confederacy in public spaces. They include the names of schools, cities and counties, parks, streets, dams and other public works, in addition to hundreds of statues and monuments that adorn county courthouses and parks across the South. Thousands more historical markers, like the one at the Forrest house, have also been planted across the region, many of them sponsored by “heritage” groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy and Sons of Confederate Veterans.

Of all of those symbols and monuments, perhaps the ones paying homage to Forrest are the most controversial.

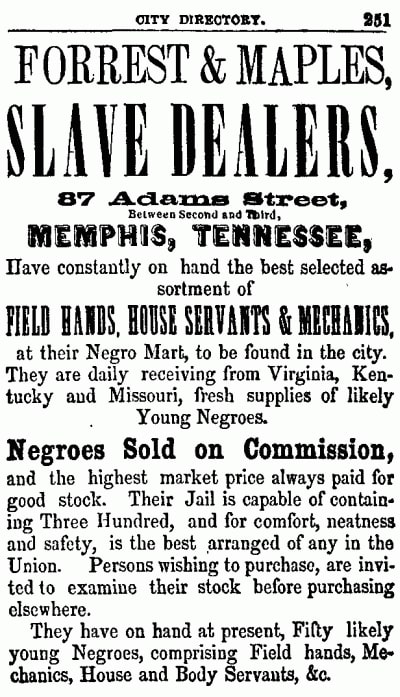

When the Civil War started, Forrest was one of the wealthiest men in the South – and like many of his peers, his wealth was based primarily on slave labor. In addition to cotton plantations, he operated a thriving slave market on Adams Street (now Adams Avenue) in Memphis, a city at the center of river and rail shipping routes. An 1850s advertisement in the Memphis City Directory touted “at present, Fifty likely young Negroes, comprising Field hands, Mechanics and Body Servants,” along with a “jail” large enough for 300 people.

As a cavalry commander during the war, Forrest is remembered as innovative and highly successful. But his reputation was forever stained in 1864 when his troops massacred black Union soldiers who were surrendering during the Battle of Fort Pillow. After the war, Forrest joined the newly formed Ku Klux Klan and became a “grand wizard,” its first national leader.

Despite the massacre and his Klan leadership, Forrest today continues to command attention as a Confederate hero in many corners of the South – in part because of at least 43 public places in eight states that contain his name or likeness.

The SPLC’s report Whose Heritage? found that there were two distinct periods in which the dedication of Confederate monuments and other symbols spiked.

The first began around 1900 and lasted well into the 1920s, during the period when Southern states were imposing Jim Crow segregation. At the beginning of this period, in 1905, a large bronze statue of Forrest astride his horse was dedicated in Memphis.

The second period was during the civil rights movement, beginning immediately after the U.S. Supreme Court ordered school desegregation in 1954. It was in 1955 that the marker at the site of Forrest’s home was installed.

“It was offensive to realize that people knew that [Forrest was a slave trader] in 1955 but were not willing to tell that story, and instead they wanted to tell the sort of traditional Lost Cause narrative of Forrest, which is that he needed to be portrayed as a hero,” said Timothy Huebner, a Calvary Episcopal member and history professor at Rhodes College. “The sign kind of fits within the heroic view of Forrest that started with the monument going up in 1905.”

Another massacre

Though the massacre of black soldiers at Fort Pillow did not prevent Forrest from becoming a Civil War icon, a more recent mass murder may have finally done him in.

On June 17, 2015, a young white man named Dylann Roof, steeped in racist propaganda he found on the internet, shot to death nine black churchgoers during a prayer service at the historic “Mother Emanuel” church in Charleston, South Carolina. In a photo that later surfaced online, Roof is seen with the Confederate battle flag in one hand and a handgun in the other.

While Roof wrote in a manifesto that he wanted to start a “race war,” he actually sparked something else, something unexpected: a nationwide movement to begin removing Confederate iconography from public spaces. Since then, state and local governments have removed at least 113 such symbols, including high-profile monuments in New Orleans.

The removals also include the 1905 statue of Forrest in Memphis. The city council in 2017 renamed and sold the park, allowing its new owners to take it down. A monument to Confederate President Jefferson Davis was also removed.

But the other historical marker, the one marking the spot of Forrest’s house, remained in place, a fact brought up by columnist David Waters of The Commercial Appeal after the Charleston massacre. “Referring to what Forrest did before the Civil War as a ‘business enterprise’ is more than insulting to more than half the population of this city,” Waters wrote in 2015. “It’s disrespectful, dishonorable and shameful.”

Facing history

Timothy Huebner, the church member and Rhodes College professor, learned about Forrest’s slave yard in 2017 while researching the neighborhood surrounding Calvary Episcopal. That fall, he assigned research projects on the Memphis slave trade to his students.

Their findings informed the text of the new marker – to help set the record straight.

The Rev. Dorothy Sanders Wells, who is black, attended the church as a college student and is now rector at St. George’s Episcopal Church in nearby Germantown. She said she had known that Calvary Episcopal, which was founded in 1832, had been built by slaves.

But learning about the proximity of the slave yard was eye-opening.

“There was just something different about a revelation that worshippers were coming to this church week after week after week with a slave auction house sitting right in the shadows and seeing that – worshipping on Sunday and coming back on Monday to transact their business to purchase children of God who looked like me,” she said during the sermon she delivered at the Service of Remembrance and Reconciliation.

To explore the possibility of erecting a new historical marker, Huebner contacted Tim Good at the Park Service. Good had earlier worked with the city of Memphis to dedicate a marker about the 1866 Memphis Massacre, during which a white mob killed dozens of African Americans and burned down churches and schools.

Good suggested the Park Service could help fund the marker with money from the Lower Mississippi Delta Fund, which can be tapped for projects promoting heritage tourism outside of national park boundaries in the region stretching south from St. Louis toward New Orleans.

Ultimately, the marker cost less than $3,000.

The Park Service approved the language on the sign, as did Rhodes College and Calvary Episcopal. No one thought it too controversial, Huebner said, though they might have 10 years ago.

The names

After Huebner’s history class at Rhodes ended, three students – Sarah Eiland, Jay Albertson and Stewart Love – continued to research the slave yard.

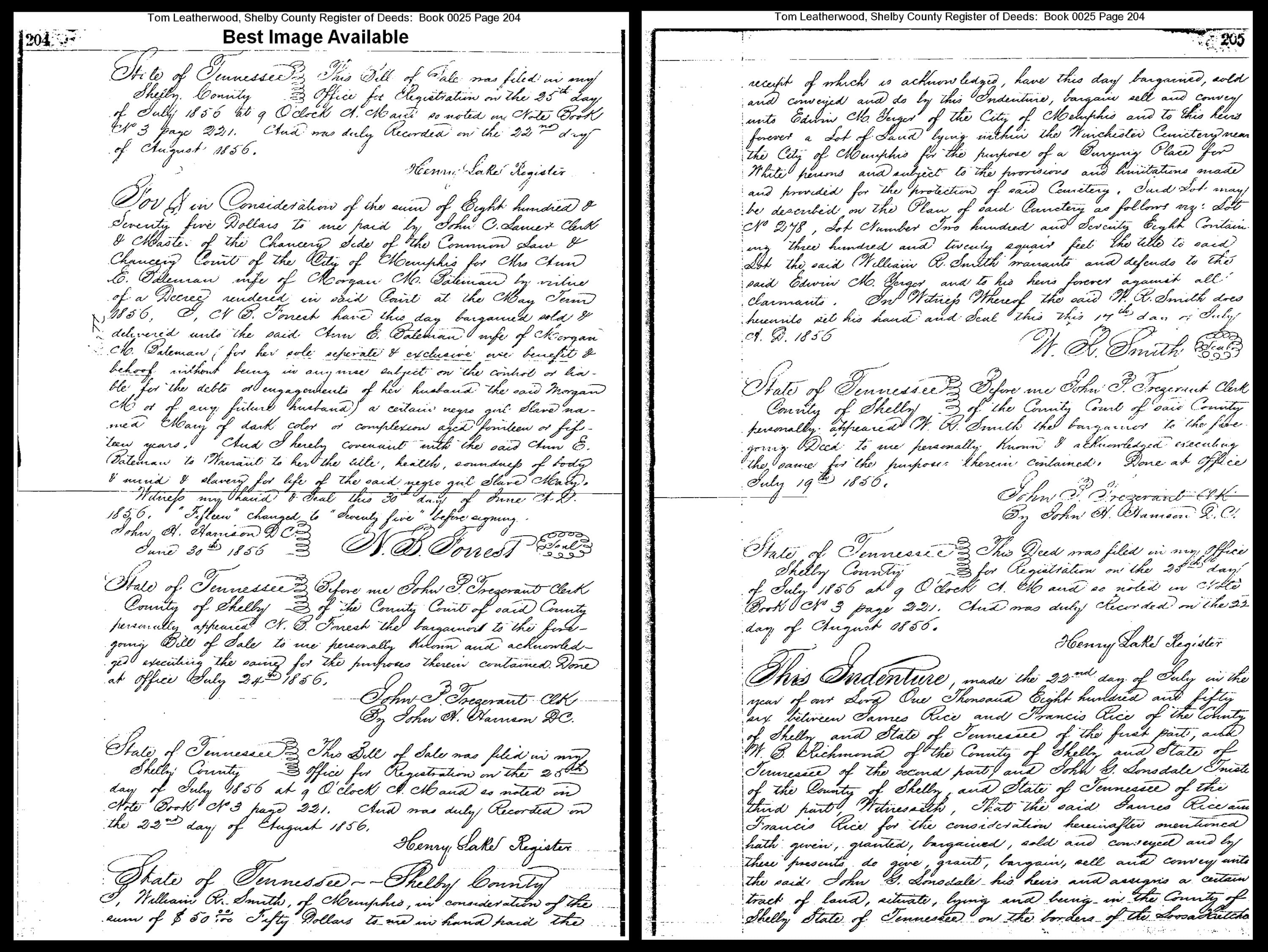

From bills of sale in the Shelby County Archives, they compiled a list of 74 people who had been sold there. Each bill of sale contained the person’s name, age, complexion and a paragraph specifying that he or she was “of sound body and mind,” Albertson said. There were, no doubt, thousands of others whose names are lost to history.

Eiland said the research process was a powerful, emotional experience, because “every descriptor is referring to a person, and every single price listed is a price put on someone’s life.”

One name hit her particularly hard: Catherine.

A newspaper article from the era referred to her as Forrest’s mistress in an attempt to slander him. Eiland found evidence of a biracial 13-year-old named Narcissa Forrest. She was Catherine's daughter.

“She [Catherine] was bought by Nathan Bedford Forrest. She was abused by him. She had a kid with him,” Eiland said in an interview. “I think the atrocities hit home with me and I couldn’t let it be looked over any more so that’s why I’m still looking into it and I’m looking into it in more cities as well.”

With the names in hand, Huebner and church officials began to plan the ceremony.

That the names would be read out loud was never in doubt. “It’s hard to figure out how do you do this in a way that’s honest and authentic and doesn’t feel contrived and manipulative,” the Rev. Scott Walters, who is the priest at Calvary Episcopal, said in an interview.

Calvary’s Service of Remembrance and Reconciliation was planned for April 4, 2018 – the 50th anniversary of the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

“The day of, we didn’t know if anybody would come, still,” Walters said.

“We thought we might have 150 people here. We knew a lot of people here were interested but there was a lot going on that day.”

The church holds 600. It overflowed.

The service

Sitting in the front pew, Huebner could not see the wave of people standing as the names were read. He heard it.

“You can’t script that,” he said. “It happened because of a genuine sense among the people there that they needed to stand out of respect for the memory of those names of people who had been sold on that site.”

Page, age 9.

Washington, age 20.

Catherine, age 23.

Eiland, who is white, was among those who spoke to the congregants. She recalled that, as a child in Mobile, Alabama, she had attended slumber parties at Confederate forts and donned the hoop skirts of an Azalea Trail Maid to represent the city. She had jogged past antebellum homes only a few miles from Africatown, where descendants of enslaved people smuggled into Alabama from the ship Clotilda still live.

“I have been numb to the true implications of the daily reminders of this era until now,” she said.

John Henry, age 6.

Mary Anne, age 3.

Sarah, age 17.

For some, the names were almost too much to bear. Wells, who wrote the litany of prayers and helped plan the service, had not looked at them beforehand. “I just wanted to allow that part of our worship to wash over me,” she said later.

When the first child’s name was read, she stood.

“As a mother, I wasn’t sure I could continue to stand, not because I didn’t want to stand in honor of them but because the grief was just overwhelming, of imagining someone snatching my child out of my arms and selling my child,” Wells said.

The past and the future

The work of Huebner and his students could be a model for other communities seeking to recognize sites linked to slavery, Good said.

More projects highlighting slavery and racial violence are beginning to appear in the South. In addition to the marker for the 1866 Memphis Massacre, Good worked with the Memphis Lynching Sites Project to install a marker at the site of the 1917 lynching of Ell Persons.

In Montgomery, Alabama, this year, the Equal Justice Institute opened the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and its companion Legacy Museum to recognize victims of lynching. The city is also home to the Civil Rights Memorial, built by the SPLC to recognize 40 martyrs of the civil rights movement.

For many, remembering the South’s history of brutality toward African Americans, is just the beginning of something larger.

“The names that we have just make it all the more precious to me that we really tackle systemic inequality in our country and the legacy of racism,” said Jay Albertson, one of the students who researched the names in Memphis. “We don’t know their lives, and that’s an indictment of America, so I don’t care that it happened a long time ago. It matters. It matters today. If it mattered then, it matters today.”

It does matter today.

During the ceremony, Wells pointed to the legacy of slavery and racism in Memphis. The unemployment rate for African Americans in Memphis is twice that of white Memphians. The city is home to a significant number of Tennessee’s underperforming schools. The median household income of African Americans in Memphis is only 60 percent of the city’s white households.

“Now it is up to us to figure out how together we move to a better place in the future,” Wells said.