Alabama Voting Rights Project helps 2,000 people cast ballots in Alabama, but many more do not know they can vote

Rodney Lofton had never cast a ballot before a felony conviction stripped him of his voting rights in 2015.

After he served his sentence, the Alabama Voting Rights Project, a partnership between the SPLC and the Campaign Legal Center, walked him through the paperwork to get his rights restored.

He got a voter registration card, and voted for the first time in his life in the November 2018 elections.

“A lot of minorities, particularly people in the black community here in Mobile, do not vote for a variety of reasons,” he wrote in a blog post for the Campaign Legal Center. “People feel disconnected from the political process, and many are confused about who can and can’t vote. Many people here think that a crime disqualifies them from voting, even misdemeanors. The state has not put much effort into educating citizens about this.”

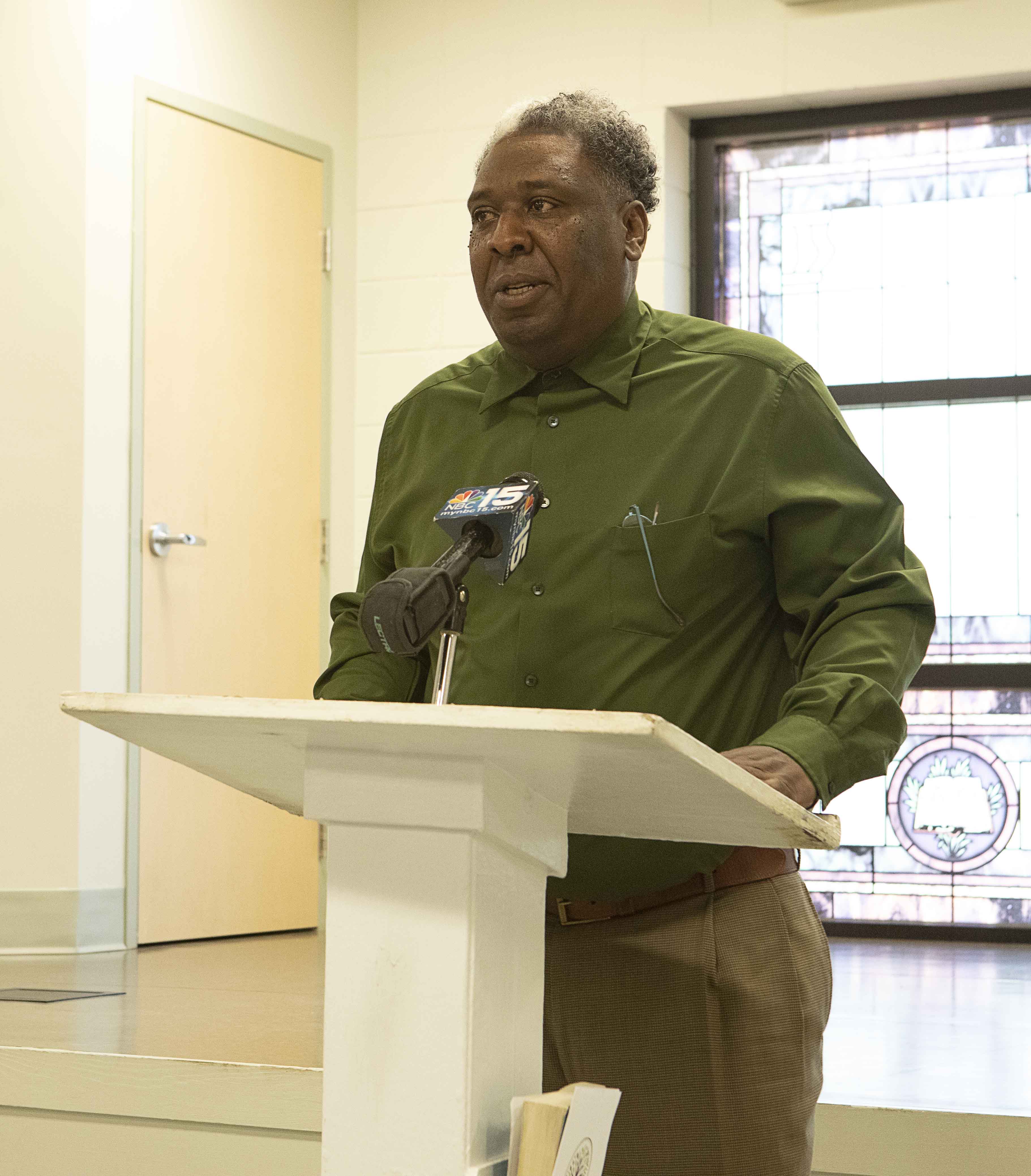

Lofton joined members of the Alabama Voting Rights Project in Mobile, Alabama, this week to announce the progress that the project has made in the effort to restore voting rights to people who recently regained eligibility, due to a change in Alabama law. Similar announcements took place this week in Birmingham and Montgomery.

Staff members and volunteers for the Alabama Voting Rights Project (AVRP) have spent the past nine months assisting Alabama citizens who have previous convictions by helping them restore their right to vote.

“To date, the AVRP has assisted 2,000 individuals with voting rights restoration and held events in and reached half of the counties in Alabama,” said Ellen Boettcher, outreach fellow for the Alabama Voting Rights Project. “While this is a great success, we still have a long way to go before we reach the tens to hundred thousand Alabamians who received their voting rights back.”

In 2017, Alabama passed the Definition of Moral Turpitude Act to specify the convictions that disqualify people from voting. Previously, it was left up to county officials to determine who could vote and who couldn’t, based on their previous convictions.

This holdover from the Jim Crow era disenfranchised 280,000 Alabamians, about 7.6 percent of the state’s voters. But it disproportionately affected African Americans. By 2016, according to The Sentencing Project, 15 percent of the state’s African-American adults had lost their right to vote.

After the law was passed, many people with past convictions had no idea they might be eligible to vote, because neither the state nor Alabama Secretary of State John Merrill bothered to tell them. Organizers with the Alabama Voting Rights Project, with assistance from other groups and individuals, have been working to educate and register these potential voters.

“Even after the passing of the Moral Turpitude Act of 2017, my burglary charge blocks me from being able to vote and that isn’t right,” said Timothy Lanier, an Alabama citizen who is still fighting for his rights. “I’ve paid my debt to society and give back to my community, and a mistake I made in my youth shouldn’t limit my ability as an adult to participate in my community’s decisions.”

Rachel Whiteley, a re-enfranchised citizen who works for a re-entry program called The Neighbor Center in Mobile, agreed.

“Getting my voting rights back has made me feel like more of a whole person, a whole human being,” Whiteley said. “I feel like everyone should have the opportunity to make a difference in the world we live in, and voting is an exciting way to do that. I feel more like a productive member of society.”

Lofton, who works four days a week at the First Christian Church in Mobile as part of the Second Chance Program, said the voting rights restoration movement is a blessing.

“I hope that more people can learn they can have their rights restored, so they can feel what I felt when I voted for the first time last November,” he said. “Being heard means a lot to me. I’ve experienced many obstacles getting to the ballot box, and I don’t take my voting rights for granted.”

Photo by Stephen Poff