Opportunity Costs: Community corrections program struggles to break even as some clients feel the pain

Kary Meadows believed he was just days away from going free.

It was June 2013. Meadows, then 42, had served three years on probation for possession of a controlled substance. A year earlier, a judge had revoked his probation for failing to attend Narcotics Anonymous meetings and ordered him to serve the final year of his sentence under supervision by community corrections in Walker County, Alabama.

Under the supervision of Walker County Community Corrections (WCCC), a nonprofit agency, he paid $10 a day to wear a GPS tracking device that was strapped to his ankle, according to court records. He also paid a $35 monthly supervision fee and $30 for each drug test, which he took almost weekly.

Meadows had been through the program before, but this time he also faced the aftermath of a recent tragedy. His 15-year-old son was murdered just four days before Christmas in 2012. Though distraught, he told a case manager he was determined to make it through the program.

As his anticipated release date approached, he failed a drug test for marijuana, court records show. He told the program director, Steven Shaver, that he didn’t care what happened to him. He expected to go to prison for the remaining days of his sentence.

Instead of sending Meadows to prison, Shaver moved him into WCCC’s residential work release program. There, Meadows would live in a decrepit former jailhouse with others in work release. He could leave for short periods to look for work on foot. When he found a job, he would go to work and then return to the facility. His other time in the community would be severely restricted. He would also pay WCCC $12 per day to live in the facility, in addition to the other fees.

It seemed like a good opportunity to stay in his community – until the day Meadows had been waiting for, the day he would be released from WCCC, never came.

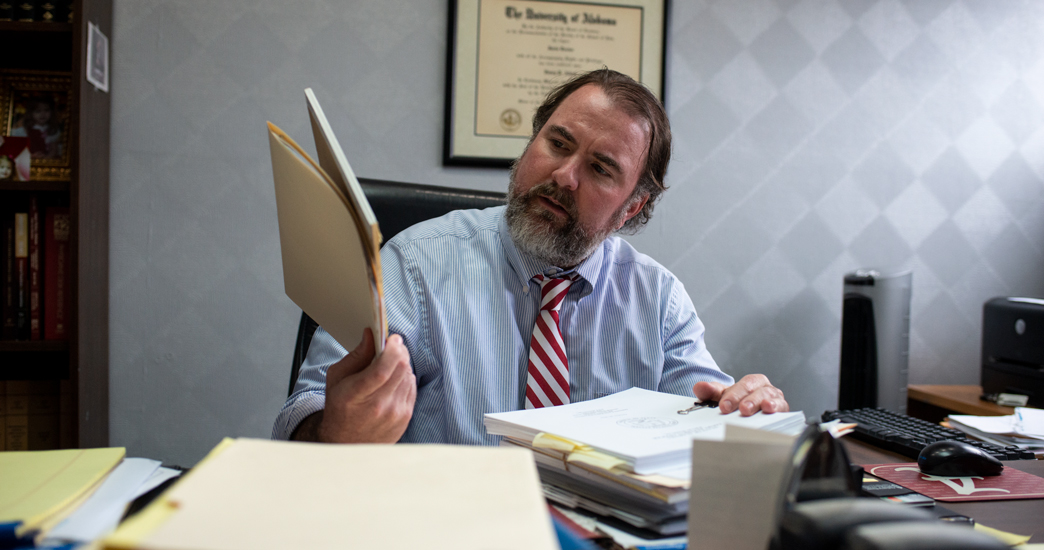

As director, Shaver had enormous authority over the lives of the people sentenced into his program. He determined whether to seek warrants to have them jailed. He assigned them to work release, had them fitted with GPS tracking devices on their ankles and had them take drug tests more or less frequently. By one account, he showed compassion to the people in his care. But he also oversaw an office where, according to a WCCC employee, officials “sometimes talk to [participants] like they’re animals.”

The SPLC’s investigation reveals that many of the problems afflicting community corrections programs in Alabama at large were common at WCCC. These user-funded programs, while holding promise for helping alleviate chronic prison overcrowding in the state, can trap people for years in a cycle of jail, work release, supervision and prison.

In Walker County, because of the program’s strict rules and its drive to generate revenue in an economically depressed county, the needs of participants too often fall by the wayside.

That’s what happened to Meadows. He needed someone to take his concern about his release date seriously, but the need went unaddressed. Over the next few months in work release, Meadows repeatedly asked about his end-of-sentence date, records show. He believed that with the “good time” he had earned, his sentence should be over.

According to court records, no one contacted the Alabama Department of Corrections [ADOC], which oversees community corrections programs, to determine whether he was right. “That’s not the procedure,” Shaver later testified.

What the organization did do was continue to charge him fees and collect his money. By December 2013, Meadows had paid thousands of dollars to WCCC, according to court records. He was making $400 per week working as a carpenter for a construction company. A significant portion of his income went to cover his fees, including rent for work release housing.

One day, on his lunch break at a work site, he called ADOC’s central office in Montgomery. He later testified that he got through to an official in the community corrections department and explained his predicament. Moments later, the official told him: “Oh my God, Mr. Meadows, you need to hire an attorney,” Meadows would later recount for a deposition.

He learned that he should have been released by WCCC more than seven months earlier, in May 2013. The date was even earlier than what he had originally expected.

WCCC is one of 37 community corrections organizations in Alabama. Local officials established it in 2007 as an independent, nonprofit entity in Jasper, the county seat, a town that lies deep in Alabama’s coal country. From the county court annex near the town square, it oversees multiple, sometimes overlapping programs – including the local drug court and a court referral program – for people caught up in the justice system who are diverted from jails and prisons.

Some participants return to Walker County from state prisons. Others are put under WCCC’s supervision in lieu of prison when their probation is revoked. And some are pre-trial defendants ordered by a judge into work release, or for drug testing, as a form of pre-trial diversion, or for other types of supervision.

WCCC generates the lion’s share of its revenue, nearly $1 million a year, from fees it charges to people like Meadows. It also received $117,261 in fiscal year 2018 from ADOC for its community corrections program and separate funding for a court referral program from the state Administrative Office of Courts. The two programs offer similar services but are overseen by separate state agencies with separate rules and fee structures. For community corrections, there is no uniform fee structure. Instead, each program determines what it wants to charge for things like drug testing, supervision fees and monitoring devices.

For this investigation into WCCC, the SPLC reviewed hundreds of pages of court records, state audits, tax forms and the organization’s community corrections plan. Interviews were conducted with a judge, the organization’s interim director, a public defender, a current WCCC employee and multiple people who have been through its programs. (An attorney for Meadows declined a request for comment from his client, whose story is recounted here through public records.)

“We get paid by our fees that we charge,” said La’Tisha Oliver, WCCC’s interim director. “Our fees are comparable, if not lower, than some of the other community corrections offices in the state.”

She added: “We take defendants to rehab, we take them to their appointments, we take them to court if they don’t have a ride, we don’t charge them for that. We do a lot of things we do not get paid for.”

Oliver took over as interim director of WCCC in July. Before that, however, some participants who experienced the office under Shaver’s direction told the SPLC they felt like they were set up to fail.

The SPLC reviewed the court cases of 44 people who were serving time in WCCC community corrections as of January 2016. A majority of them (29) spent extra time in jail or prison for rule violations that ranged in seriousness from failed drug tests to “being disrespectful to work release staff.”

Fourteen of the 44 people went through WCCC’s drug court program either before or during their time in community corrections. There, they faced stringent drug testing requirements and steep fees. Twelve of those violated the terms at least once, leading to incarceration in jail, prison, or community corrections. There, too, the violations ranged in seriousness; some people failed drug tests, others broke work release rules. One woman in drug court was jailed because she was “observed getting into a vehicle with a known sex offender.”

For a few, like 45-year-old Janet Gomez, there was another stop in the circuit of jail, work release and prison. While they remained under WCCC’s supervision, the court ordered them to attend a year-long Christian rehabilitation program in Anniston, Alabama, called Center of Hope. The facility is similar to those examined across the country by the Center for Investigative Reporting.

Center of Hope is not a state-certified treatment facility and requires participants to work for no pay, according to the center’s administration officer.

It’s against ADOC rules for community corrections organizations to send people to noncertified treatment facilities. But a statewide shortage of beds in certified facilities, along with lax ADOC oversight of community corrections organizations, means people end up in noncertified rehabs anyway. Four of the 44 people, including Gomez, ended up in treatment facilities by court order while under community corrections supervision, three of them at Center of Hope.

“[Center of Hope] put me in a thrift store … they make you work there for free,” said Gomez, who spoke to the SPLC in March.

Like others sent there, she could not leave without permission from WCCC.

Gomez also said she spent time in WCCC’s drug court and work release program. For a while, she wore a GPS device strapped to her ankle.

“I wanted to come forward [to tell my story] a long time ago but I was scared. It’s about drove me crazy,” she said of WCCC.

In 2010, while she was struggling with substance use disorder, Gomez forged 25 checks. She was arrested on May 3, 2012, and later pleaded guilty to three counts of possession of a forged instrument. Under her plea agreement, consecutive 10-year sentences for each count would be suspended and she would enter drug court. She began WCCC’s drug court program shortly thereafter. Over the next year, she spent time in its work release facility for violating rules, though court records do not make clear which rules she violated.

By December 2013, she said she showed symptoms of severe depression. “A month before I was supposed to graduate in drug court, I thought I’d took all I could take, and I tried to kill myself,” she said.

She made an attempt on Dec. 13 and spent the next week in a Birmingham hospital.

Immediately after her hospital stay ended, a Walker County judge issued a warrant for her arrest. “Defendant has violated the terms of Walker County Drug Court Program. [She] has had several prior sanctions and is non-compliant with the program,” it read. The arrest warrant did not specify which rules she violated.

Gomez was headed to prison. But it wouldn’t be long before she returned to WCCC.

“I’m telling you, my nerves are shot because of this place,” she said.

Less than three weeks after officers arrested Gomez, on Jan. 10, 2014, WCCC released Kary Meadows.

He had hired an attorney, who got the judge to issue an order giving Meadows “due credit against his said sentence.”

He went free.

A clerical error was to blame for Meadows’ wrongful incarceration, which lasted seven months and 14 days beyond his release date. When his probation was revoked and he began his time in community corrections, no one prepared a transcript for the case and sent it to ADOC. As a result, ADOC did not send the correctly calculated end-of-sentence date to Shaver.

On March 16, 2015, Meadows filed a civil rights lawsuit alleging that WCCC and Shaver “were grossly negligent or wanton in their failure” to release him on time.

Shaver responded that he could not calculate Meadows’ release date, much less let him go free, without the proper paperwork and permission from ADOC. Still, Meadows testified on Aug. 25, 2015: “I do blame Shaver. He is the director, I was under his authority. It was his job to know when I got there and when I’m supposed to leave.”

Meadows’ lawsuit sought to recoup the money he had paid in fees while he was wrongly incarcerated. During a 2015 deposition, he asked Shaver’s attorneys: “What did they do with my money?”

In fact, like other community corrections organizations in Alabama, WCCC is a nonprofit entity. Its tax filings show it has generated millions of dollars in revenue by charging fees to participants for drug testing, GPS monitoring, work release housing rent and more. According to the filings, the organization brought in $7.1 million from 2006 to 2016. Much of the money came directly from people like Meadows and Gomez, both of whom have applied for indigent status in their cases.

But WCCC has struggled to stay in the black. Expenses included almost $600,000 for salaries and benefits for WCCC employees in fiscal year 2016. The organization spent more than $426,000 on “other expenses,” including $120,078 for “drug testing expense,” according to tax filings. Shaver’s reported salary was nearly $60,000 in fiscal year 2016, $40,675 in fiscal year 2017 and, after a massive pay cut, just $16,800 in fiscal year 2018. It reported $938,448 in total revenue on its most recent tax filing, gaining a net $14,314.

Compared to some other community corrections organizations’ revenue, WCCC’s is significant. By comparison, an organization covering several counties in southeast Alabama had $252,453 in total revenue during roughly the same period.

“What can we do and break even, and not go broke doing this?” said District Judge Henry Allred, who until recently served on the WCCC’s board of directors while also ordering people into its programs. Allred was not paid for his role with WCCC.

The SPLC interviewed Allred in his Jasper office in March. He said WCCC’s “guiding philosophy” involves weighing the fairness of the system for people who commit crimes against the need to generate revenue to continue operating. Some revenue comes from ADOC, but the department provides $10 per day for most participants in the community corrections program, a rate that in most programs doesn’t come close to covering costs.

There are geographic disadvantages for WCCC, too. “It’s kind of a depressed economy in Walker County,” Allred said. “This is a coal-mining community. When the coal mines shut down, a lot of people were out of work. What we try to do is be fair with people. You’ve got to charge enough to break even, but you don’t want to put people in a position where they’re set up to fail.”

But with more than one-fifth of the county’s residents living below the federal poverty threshold that can be difficult. The county’s unemployment rate is 4.2 percent, but national studies suggest that people who get entangled in the criminal justice system are more likely to be unemployed or have low-paying jobs. A 2018 study by the Brookings Institution found that “three years prior to incarceration, only 49 percent of prime-age men are employed, and, when employed, their median earnings were only $6,250.”

Despite the obvious fact that most participants struggle to keep up with the fees while trying to get their lives back in order, WCCC needs the money just to stay open.

Allred acknowledged that the system is imperfect.

“Personally, I would say, if you can’t do the time, don’t do the crime,” he said. “It’s the system we have. There’s got to be some accountability on people who are committing crimes over and over and over again. I don’t think it’s a perfect system; I think there’s a lot wrong with it. But I don’t know of a better one out there.”

When Meadows filed his lawsuit in 2015, Allred and his fellow judges recused themselves because of their relationship with Shaver and WCCC.

The WCCC director works closely with the court, Allred explained. If someone fails a drug test, the director will alert the judge. “And I might say, ‘Well, keep him in work release on a more restricted level,’ or I might say, ‘Put him in the county jail until we can talk, and figure out what’s going on.’”

Indeed, WCCC exists to give the court options and alternatives to prison and jail. But Allred has explored using WCCC’s programs in ways he admitted give him concern, like ordering pre-trial defendants into work release when they cannot afford to pay their bond. Such options get people out of jail while also expanding WCCC’s base of fees-paying clients.

The SPLC found several cases of pre-trial defendants ordered by Allred into work release as a condition of their bond.

In one case, Allred set a $30,000 property bond for an indigent woman facing her first offense. When she couldn’t pay it, she asked Allred to reduce her bond or let her into work release. “I have no one to post my bail,” she wrote to him in a letter. “I want my children back, sir. They are my life. … I’m asking for either a bond reduction, a plea that you grant me a signature bond and/or allow me to be released from jail into work release.”

Allred lowered her bond to $0 and ordered her into work release as a condition. The woman eventually pleaded guilty. Her sentence was supervised by WCCC. In work release, she got a job as a cook at a barbecue restaurant earning $375 per week, according to court records. She paid $85 a week to WCCC to cover her work release rent.

The local public defenders balk at such practices.

“It’s a beautiful system for sucking money out of the people who can least afford it,” said Sam Bentley, who represents many indigent defendants in Allred’s courtroom as the county’s public defender. He said he understands the need to “break even” but thinks WCCC’s programs should be means-tested and its fees proportionate to each person’s ability to pay.

“Whether you call yourself a nonprofit or not, if you have a profit incentive – and somebody seems to have a profit incentive – then the cost is going to be borne on the backs of the indigent people who are charged, who are in the system,” Bentley said.

Janet Gomez returned to Walker County to finish her sentence in community corrections in November 2014. She went straight from prison into work release. In the work release facility, she saw rats and roaches, she said. Gomez also recounted how she and other women in work release had to stand on a chair in the shower to stay out of backed-up water. She received little assistance with finding a job and had to search on foot. Many participants find work at the Mar-Jac poultry processing plant less than a mile from downtown Jasper, but Gomez said she never found a job.

Eventually, she was released into the community with a GPS monitor strapped to her ankle. WCCC allowed her to come off the GPS device in mid-2015.

But Gomez still struggled financially. In a May 2017 court filing, she indicated that she was disabled and received $900 per month. She spent $700 on expenses like food and utilities. On top of that, she had to pay WCCC’s fees.

Last December, after her brief stint at Center of Hope was cut short by health issues, Gomez became fed up with WCCC. She said she stopped responding to the frequent calls to come in to the office. “It’s just harassment,” she said.

“I walked away from it. I can’t take it anymore. I told them that I was tired of being treated the way I was treated,” she said.

Gomez showed the SPLC a receipt from Dec. 27, 2018, five years to the day after she was arrested and later sent to prison. It showed she still owed $347 to WCCC when she walked out.

Meanwhile, Meadows had a setback in his civil rights suit against Shaver. In August 2018, a judge ruled that Shaver and WCCC were not responsible for filing the missing paperwork that would have led to him being released on time. “Defendants did nothing that caused others not to perform these duties,” the judge wrote. “The defendants did not have a duty to perform this task.” Meadows appealed the ruling.

WCCC Interim Director La’Tisha Oliver heard about the Meadows lawsuit only in passing after she joined the staff at WCCC in January 2015. “You would always hear, ‘Kary Meadows.’ And I thought, maybe it’s just another inmate that’s in trouble,” she said recently. Shaver, the director at the time, never held a meeting to tell the staff what was happening or that the organization was being sued, Oliver said.

But in late 2018, things suddenly began to change at WCCC. Shaver abruptly resigned his position as director just after Christmas. The reason is unclear. His exit came less than a week after the SPLC sent the organization a detailed public records request seeking documents related to work release, revenue and success metrics. Shaver did not respond to repeated calls seeking comment.

Allred left the board in the months after his interviews with the SPLC. The WCCC board is now searching for a new director for the community corrections program. Meanwhile, Oliver continues to serve as WCCC’s interim director. The organization has shuttered its work release program, which Oliver called a “large liability.”

“I think there were issues before,” Oliver said. “We [the staff] felt like we didn’t have any say. Now, we all feel like we have a say in what goes on here. And I think for the most part, our attitudes are so much better. We don’t try to keep our thumb on anyone, because that’s not what we’re here for. We’re first here to help and we’re here to supervise. But between all that, I think we’re obligated to go above and beyond normal, because our jobs aren’t normal.”

Oliver acknowledges, too, that Kary Meadows “fell through the cracks.”

“A lot of that could have been prevented,” she said.

Bentley, the public defender, feels optimistic about the changes in leadership. In his view, the organization need not ax its revenue-generating programs.

“I don’t object to those things on their face,” he said. “My objection comes in when it’s so financially burdensome on the client that they end up, basically, failing out of the system because they can’t afford it.”

Oliver and the WCCC board could turn to other counties in Alabama for ways to improve their programs. Some community corrections organizations appear to set people up to fail in similar ways to WCCC. They have work release programs with high fees and are quick to jail people for simple rule violations.

But some community corrections organizations mitigate, at least, the flaws in the user-funded justice model. For one, they employ more evidence-based practices. At the University of Alabama in Birmingham, the Treatment Accountability for Safer Communities, a national association, has developed a database to better track outcomes. And in southeast Alabama, a community corrections organization simply charges more reasonable fees and waives them when necessary.

Regardless, change at WCCC came just too late for Kary Meadows and Janet Gomez. Meadows’ civil rights suit is at the mercy of Alabama’s appellate courts.

And on April 10, sheriffs’ deputies arrested Gomez for failing to report to community corrections. She was charged with first-degree escape on May 1. The charge was dropped, but a judge revoked her ability to stay in community corrections, citing Gomez’ refusal to submit to drug tests.

She was ordered to return to prison to serve the remainder of her sentence.

Return to the Opportunity Costs: Unequal Justice in Alabamas' Community Corrections Programs landing page.