Arbitrary & excessive: Marijuana trafficking sentences in Alabama

Alabama resident Lee Carroll Brooker garnered national attention in 2016 when the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the marijuana trafficking case that put Brooker, in his 70s at the time, in prison for life.

“It’s been a nightmare, since all this stuff started,” his son, Darren Brooker, said.

The elder Brooker, a disabled veteran, was 72 when he and Darren were arrested and charged with trafficking in 2011. Darren was 45. At the time, Lee used marijuana to alleviate the pain of several medical conditions, including issues caused by nerves in his neck and spine and debilitating anxiety, according to court documents.

The weight of the plants found at the Brookers’ residence added up to roughly 3 pounds – beyond the threshold of 2.2 pounds necessary for a trafficking in cannabis charge in Alabama, among the nation’s lowest thresholds for marijuana trafficking. Because Lee was convicted for a string of robberies 20 years earlier and marijuana trafficking is considered a Class A felony, he was sentenced to life without parole under Alabama’s Habitual Felony Offender Act.

It was such a harsh sentence, even conservative firebrand Roy Moore, then the Alabama chief justice, wrote a brief in 2015 describing the sentence as “excessive and unjustified.” Nevertheless, the state’s high court upheld the sentence. A year later, Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Initiative appealed Brooker’s case to the U.S. Supreme Court, which refused to consider it. Brooker remained behind bars until Nov. 5, 2019, when he was released on medical furlough to live with his son.

He’s now 81.

The experience left the father and son reeling. “The money it's cost … the unbelievable amount of money it's cost me,” Darren said about legal fees and fines since the arrest. “And when it happened, you know, I lost my job, and everything, because it was pasted all over the papers and all that crap. You know. And it was a bad deal, man. It really was.”

The elder Brooker, however, is not the only person to face a life sentence under Alabama’s harsh – and arbitrary – marijuana trafficking laws. Earlier this year, an SPLC investigation found there were six people serving life sentences in Alabama prisons for marijuana trafficking. The weight of the marijuana in those cases ranged from 2.8 pounds to 25 pounds, according to court documents.

“From my perspective, two pounds is something that your standard dealer could have,” Hayden Griffin, director of Graduate Studies in Criminal Justice at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. He added: “Trafficking is almost kind of like smuggling, or bringing it into the country, things like that. You would never see a small prop plane with nine pounds of marijuana in it.”

‘Randomly drawing lines’

Yet trafficking in cannabis in Alabama is a felony that carries a mandatory minimum sentence of three years imprisonment and is considered a violent offense – regardless of whether it’s simply a matter of someone possessing a relatively large quantity of marijuana. And prosecutors and judges have significant discretion, because drug trafficking offenses are not covered by the Alabama Sentencing Guidelines.

All of this means that, theoretically, trafficking in cannabis – even as a first offense – can carry a sentence anywhere from the three-year mandatory minimum to life in prison in Alabama. What’s more, an SPLC analysis of the cases of 50 individuals in custody of the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) for trafficking marijuana found harsh sentences for varying amounts of marijuana, few indications of violence and that over one-third of the individuals were convicted in a single county, demonstrating the power of local prosecutors in sentencing.

Of the 50 cases for individuals in ADOC custody for marijuana trafficking at the time of this investigation, only 34 documented a specified weight in the arrest warrant, criminal complaint, indictment or any forensic analysis. Of those cases, 50% noted marijuana quantities less than 10 pounds.

By comparison, South Carolina defines trafficking in marijuana as 10 pounds or more, while Florida defines trafficking in cannabis as 25 pounds of marijuana or at least 300 cannabis plants. And, in most neighboring Southern states that don’t have verbatim marijuana trafficking statutes, there are marijuana distribution or sale statutes, which have higher weight thresholds and lower mandatory minimum penalties than Alabama’s trafficking statute.

In other words, a person who would be charged with trafficking in marijuana in Alabama would likely face a lesser charge and a lesser penalty if caught with the same amount of marijuana in most neighboring states.

Data by State

Please view this page in landscape mode to view this chart (turn your device 90 degrees to the left or right).

| State | Minimum Weight Thresholds for Marijuana Trafficking Offenses | Mandatory Minimum Sentence Triggered |

|---|

If this patchwork of laws across the South isn’t disparate enough, at the federal level, the U.S. Controlled Substances Act mandates a penalty of five years imprisonment for trafficking more than 220 pounds of a substance containing marijuana or more than 99 marijuana plants.

“In many ways, the wide variety across states about where these cutoffs are between possession and trafficking make it pretty clear that they’re not actually grounded in any actual sense of harm or safety or anything like that,” said John Pfaff, professor of law at Fordham University School of Law. “They all have different cutoffs with different implications. It suggests that they're sort of randomly drawing lines based on unempirical instincts.”

The national mood in the late 20th century likely shaped Alabama’s drug trafficking law, said Rob Mikos, a Vanderbilt University law professor and an expert on marijuana law and policy. “The late seventies to early eighties was really a get-tough-on-crime period,” he said. “Lots of legislatures, including the federal government, started to shift from more discretionary sentencing of offenders … to more rigid sentencing schemes.” New laws dealing with marijuana in particular were part of an “overall wave, just a very get-tough-on-crime mentality,” he said.

Alabama lawmakers set the floor in the 1980s by establishing a mandatory minimum sentence for marijuana trafficking but allowed prosecutors the discretion to seek sentences that vary greatly in length.

The SPLC’s analysis found sentence length has little to do with the amount of marijuana at issue. For example, at the time of this investigation, Joel Hogan, 57, was seven years into a 30-year term at Frank Lee Work Release Center for possessing 5 pounds of marijuana, while David George Scott, 36, was serving a three-year term for possessing 120 pounds of marijuana, according to court documents.

No enhancements, such as possessing a firearm or being a habitual offender were indicated in sentencing dockets in either case. The only notable difference beyond the marijuana quantities is that Scott pleaded guilty, and Hogan exercised his right to a jury trial.

The key to understanding the disparity boils down to a lack of sentencing standards for drug trafficking offenses and the designation of trafficking as a violent offense. Alabama has sentencing standards for crimes determined to be “the most frequent felony convictions,” like assault and burglary. But there are no such standards for trafficking in marijuana.

Including drug trafficking in the state’s sentencing standards, however, would not singlehandedly solve the problem. Since drug trafficking is considered a violent crime, such standards would not be “presumptive,” meaning judges could choose whether to follow them.

“When the Legislature makes that list of what’s violent and nonviolent, the [Alabama Sentencing Commission] is only allowed to have presumptive sentencing guidelines for nonviolent cases,” said Bennet Wright, executive director of the commission.

As a result, sentences vary widely, with apparent unfair disparities.

A violent offense?

And yet the SPLC’s analysis found that it’s difficult to see how marijuana trafficking even fits the state’s definition of violent crime.

Offenses on the state’s list of violent offenses must meet one of four criteria, according to the law. The first requires that “the offense has as an element, the use, attempted use, or threatened use of a deadly weapon or dangerous instrument or physical force against the person of another.”

However, in the 50 cases reviewed by the SPLC, the sentencing enhancement for possession of a firearm in the commission of the trafficking offense – which mandates five extra years in prison if applied – was applied only once. And in just 10 of the 50 cases, a firearm appears to have been seized at the time of arrest.

Even in cases in which the defendant had a gun, it’s difficult to spot a violent element or “threatened use” of the weapon. For example, when Leon Hotchkiss, 65, of Baldwin County was arrested in 2011 for marijuana trafficking, a .22-caliber pistol was found in his laundry room. In a letter to the SPLC, he noted that the pistol was “in a box, in a laundry bag, that my older son brought down with him for him and my youngest son to shoot at targets. …There were no bullets in the gun or in the house.”

Hotchkiss, who was growing the marijuana for additional income while unemployed, eventually pleaded guilty. At his sentencing hearing in January 2013, an assistant district attorney brought up the gun and a prior conviction for possession with intent to distribute marijuana from 1990.

“There was a handgun found in the house, Your Honor,” the prosecutor said, according to records of the proceeding. “There was a high-school-aged son either living there or staying there on a regular basis. [Hotchkiss] told the officer he basically made a conscious decision to make his living this way, selling marijuana … and because of all those reasons and the prior conviction, the State would ask for life in the Department of Corrections.”

Records show the judge did not formally apply the firearm enhancement at sentencing. Nor did he formally apply habitual felony offender enhancements in Hotchkiss’ case. Yet moments after the prosecutor spoke, the judge nonetheless sentenced Hotchkiss to 40 years in prison.

The remaining criteria for violent offenses in Alabama law are “a substantial risk of physical injury against the person of another” and “a nonconsensual sex offense,” or an act that is “particularly reprehensible.”

“I think that drug trafficking should not be classified as a violent crime off the bat,” Pfaff, the Fordham law professor said. “Things should be classified as violent crimes when they involve actual violence. The justification given is that drug trafficking by its very nature is inherently a violent enterprise. The risk of violence is always there…[But] especially for marijuana, I’m not sure that’s presumptively true.”

Beyond disparities in sentencing, the designation of trafficking as a violent offense means that people convicted of trafficking face other collateral consequences. Judges may wrongly consider them “violent offenders” when they seek sentence reductions and they may face several barriers to employment after incarceration.

The power of prosecutorial discretion

While Pfaff agreed drug trafficking should not be considered a violent crime on its face, he cautioned, however, that more restrictive guidelines could backfire if prosecutors or judges navigate around them.

A glaring example of the power and reach of prosecutorial discretion can be seen in the SPLC’s data. Among everyone in the SPLC’s dataset, a plurality – 16 of 50 – were sent to prison from Madison County, which includes Huntsville and is the state’s third-most populous of 67 counties. Madison County had more than three times as many marijuana trafficking convictions as any other county in the SPLC’s dataset of people incarcerated in the Alabama Department of Corrections as of February 2020.

However, in a separate dataset compiled by the SPLC containing over 300 arrests for trafficking in cannabis above 2.2 pounds and below 100 pounds between 2015 and 2019, Madison County’s arrests are not a plurality. Instead, there are many more arrests from more populous areas like Jefferson County and Mobile County.

In many instances, individuals in these cases pleaded down to possession charges. The fact that more people might be arrested for trafficking marijuana elsewhere, but convictions appear to be concentrated in Madison County, suggests the power prosecutors exercise at sentencing.

“That is a good example of ... just how much prosecutorial discretion can shape outcomes, you know, even in fairly conservative states like Alabama,” Pfaff said.

Chad Morgan, a Madison County-based defense attorney, said the county’s prosecutors are less likely than prosecutors elsewhere to negotiate plea deals favorable to defendants. Morgan represented two people who were in prison for marijuana trafficking at the time he was interviewed for this story.

“If [the prosecutors] get the amount they need for trafficking, they’re not willing to wheel and deal as much as they are on other cases – [when] you get above that 2.2 pounds,” he said.

For instance, several people in the SPLC’s dataset who pleaded guilty in Madison County accepted deals that gave them a “10-split-3” sentence. This means a sentence stretches over 10 years on paper but is “split” between the mandatory three years of incarceration, and the remaining years on probation or suspended entirely.

In general, prosecutors can offer defendants plea deals that reduce the charge from trafficking to some other offense that carries a lesser sentence. But they also have the power to “modify the split” in trafficking cases, Morgan said. For example, prosecutors can seek a sentence that places defendants on probation for a certain period first, before sending them to prison to serve the mandatory three years in what is called a “reverse split.” In these cases, if the defendant completes probation, the rest of the sentence is suspended and the defendant avoids prison.

In Madison County, however, prosecutors don’t often stray from the “10-split-3,” according to Morgan, whereas prosecutors in other areas might. What’s more, Morgan also said the prosecutors in Madison seek severe sentences when defendants in trafficking cases reject plea deals and exercise their right to go to trial.

“If you take it to trial and they get a chance to sentence you, or the D.A.’s office gets to go after you, they try to punish you for having a trial,” he said. “It’s kind of an unwritten rule, and kind of unspoken about. I’ll speak about it all the time, I don’t care. I think it’s wrong. If they get you found guilty, they try to hammer you.”

Morgan said he believed such harsh punishment for marijuana trafficking is “ridiculous.”

“[This is a] good reminder, oftentimes that you know the problems we see in criminal justice, they are often incredibly local,” Pfaff said about the county-by-county disparities in sentencing. “Even when we sort of know that this state has a problem, it's usually not a state, it's usually like a county or two.”

Derek Yarbrough, who represented Darren Brooker in the trafficking case, also noted the disparities. “It’s so different from judge to judge, county to county,” he said. “They really do need to add marijuana trafficking to the sentencing guidelines, because the difference in sentences from county to county can be tremendous for the same crime.”

Coming home

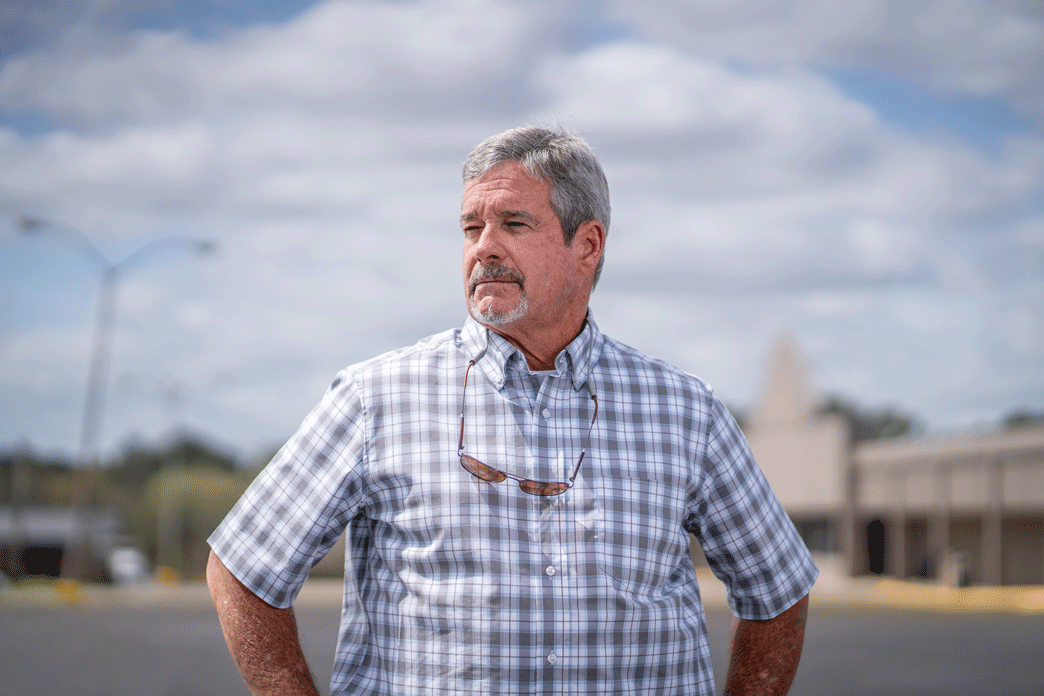

Before Lee Brooker was allowed to come home on medical furlough, his son Darren had to move back to Houston County from the Florida Keys and find a place for them to live. Darren had long finished his sentence, receiving a “reverse split” sentence that allowed him to avoid incarceration unless he violated the terms of his sentence. Despite having to leave a good job behind, he did what was needed to get his father out of prison.

“They put him in the worst prison, where all the death row inmates are,” Darren said, referring to Holman Prison. When his father came home, Darren said, he weighed just 114 pounds, though he stands 5-foot-11.

Darren said his father must call and check in with officials twice a week as part of his furlough. He cannot leave the house alone, and if he leaves with Darren, he must be home by 9 p.m. “It’s basically house arrest,” Darren said. The custody level prevents the two from moving back to Florida, where Darren said he could take much better care of his ailing father.

Alabama is a long way from joining the 11 states across the country that have legalized recreational use of marijuana. However, a bill that would allow for use of medical cannabis was approved by the Alabama Senate in early March. Additionally, a separate bill introduced this year, H.B. 91, would reclassify all instances of possession of marijuana for personal use to a Class A misdemeanor, which is punishable by no more than a year in county jail. The offense can currently be charged as a Class C felony punishable by no more than 10 years but no less than a year and a day in prison. S.B. 267 would establish a fine-only penalty, with an expungement right, for anyone convicted of possessing less than two ounces of marijuana.

For Darren, it seems his and his father’s ordeal could have been avoided completely had medical marijuana been legal in 2011. But it was not legal in Alabama, and the Brookers received a punishment that Darren believes did not fit the crime.

“It’s just been beyond excessive, what we’ve been through,” Darren said. “I don’t even know how to put it into words.”

For information about the methodology of this research, please click here.

Photos by Scott Kennedy