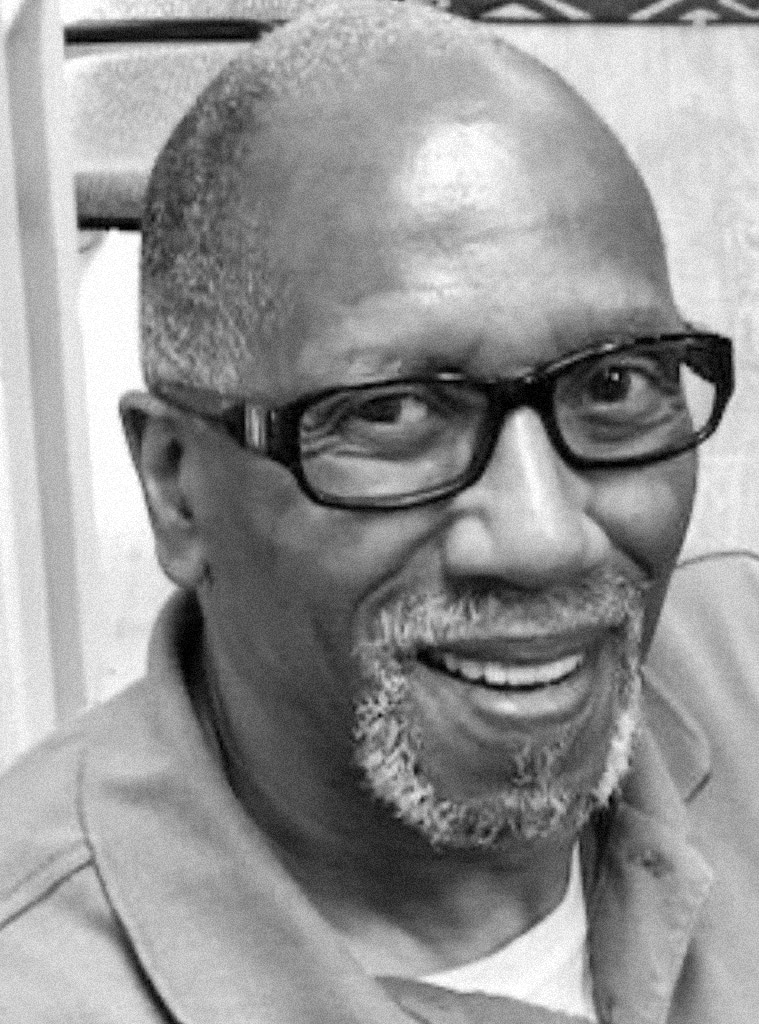

Alabama law raised obstacles on his five-year journey to the ballot box. Richard Williams overcame them all.

Richard Williams had an epiphany on his birthday in February 2013.

He was living in a house in Huntsville, Ala., with nearly a dozen men who, like him, were recovering from substance use disorder. “I turned 58. And it hit me like a ton of bricks: I am 58 years old, sleeping on a top bunk in a house with a bunch of men. Now, I thank God for that situation, because I was good,” Richard told the SPLC. “But the reality is, man, I'm missing it. I'm not where I'm supposed to be. That sparked the fire into me.”

He set a series of goals for himself. He would continue to avoid drugs. He would pay off his debts, then get his Alabama’s driver’s license and a car. And he would get registered to vote.

What Richard didn’t realize at the time was how difficult it would be to get registered, were it even possible, given Alabama’s confusing felony disenfranchisement law. That law would later change as Alabama legislators—after years of advocacy from voting rights and criminal justice organizers—narrowed the list of disqualifying offenses for purposes of voting.

Richard had been convicted of theft of property, a felony. Alabama law has for decades blocked a disproportionate number of Black people convicted of felonies from the ballot box. And more recently, the state has failed to alert potential voters when the revised law clarified their eligibility to register to vote. The process for getting a certificate of eligibility to register to vote—called a “CERV”—is confusing and requires payment of any outstanding fines and court fees associated with the offense. And delays and errors in CERV paperwork, which is handled by an overburdened state agency, have exacerbated the problem.

Richard would ultimately cast a ballot in the 2018 general election. But that was far from certain in 2013, and much less when he arrived in Huntsville from Oklahoma seven years earlier.

Back then, he used crack cocaine. Police in Huntsville arrested and jailed him for possession in late 2006. Those charges were dropped, but his struggle did not end. “I took this lady's car,” he said. “She gave me the keys, I left, and I just didn't come back.”

He was charged with theft of property in the first degree. A magistrate judge signed his warrant on his 52nd birthday in 2007. He pleaded guilty and was placed on probation for three years. He continued to use drugs, court records show, up until at least 2009.

However, he managed to complete the probation in August 2011. Not long after that, he arrived in the nonprofit-operated “program house” for recovering men, where he lived on his 58th birthday. After his epiphany, Richard paid off thousands of dollars in fines and court debt. He worked steadily as a hairdresser.

“I stayed in that house for over two years because I didn't want no more drugs, I didn't want more pain.”

Democracy was an important part of life for the house’s inhabitants. “You vote, and you have a house president, so to speak,” Richard said. “We all came together. If somebody wants to come to this house, we all come together and we vote on it, if the person should come in or not. They have to come in, talk, give us their spiel, and then we vote to see if we want them in or not.”

But Richard still could not vote in public elections.

“When I finished my probation, I [tried to register] to vote,” he said. “And I was clearly denied. And I never stopped wanting to vote.”

Alabama’s felony disenfranchisement law blocked him. The law is rooted in Alabama’s explicitly white supremacist 1901 constitution. Prior to the law being clarified in 2017, county registrars applied their own definition of crimes involving “moral turpitude” when determining whether a person was eligible to vote.

To vote, Richard needed a pardon, which he applied for in 2016. He scheduled an interview with parole officers in November of that year.

“I went in, and we did an extensive, long thing about my past. It was so intense. It took us a few hours. And I kind of started getting discouraged, you know, I started thinking to myself: Should I be able to vote? Would I allow myself to vote? Because it didn't sound that good.”

Richard didn’t get the pardon.

Then, when Alabama reformed its felony disenfranchisement law in 2017, the implication for Richard was enormous. Theft of property in the first degree was clearly defined as a “crime of moral turpitude” that doesn’t require a convicted person to get a pardon before they can apply to be eligible to register to vote. Because he had already paid off his court fees and fines, that meant Richard could regain his eligibility to register to vote by applying to the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles.

But because state officials failed to effectively publicize the change, Richard didn’t hear about it until it was nearly too late to vote in the 2018 general election. Instead, he heard about the reform from a woman one day while he was doing her hair.

“I don't know how we got into this conversation, but we started talking about it, and she says aw, let me help you out. So I went that very day and got the form from her.” He filled out the paperwork, provided by the Alabama Voting Rights Project, and mailed it in.

“About 40 days after that … it was the last day to register to vote,” he said. “When I came home and I got my mail, there was a letter in there that said, we've reviewed your situation, go register to vote. And I got up and I went that very day, because that was the last day. And I registered to vote. And I've been voting since.”

Just in time, Richard had accomplished another one of his goals.

In the interview with the SPLC, he said why it was so important to him. “People died to give me the right to vote,” he said. “And in voting, we all have a voice.”

Read more profiles from the Fight to Vote series here.

Lead photo by iStock