Has Accountability For Big Tech Come Too Late?

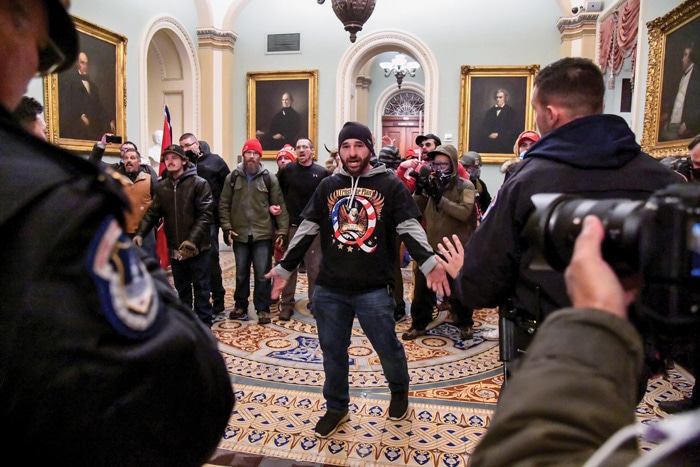

As the turmoil of the Trump era drew to a close with an attack on the U.S. Capitol, planned on both mainstream and fringe digital platforms, tech companies found their policies governing extremism tested like never before.

Former President Trump’s efforts to discredit the 2020 presidential election put our democracy under tremendous strain, using technology as a cudgel. In so doing, he followed in the footsteps of authoritarians throughout the world who use technology, including social media platforms, as a weapon. These efforts were on full display before and during the presidential transition, when Trump and his allies weaponized social media to spread lies and conspiracy theories about the election being rigged. His baseless allegations of fraud culminated in an attack on the U.S. Capitol that left five people dead, and 140 law enforcement officers injured. The supporters who coordinated the insurrection did so using a combination of mainstream social media platforms and fringe apps catering to and favored by the far right.

Rather than come as a surprise to tech companies, the events of 2020 and early 2021 ought to serve as stark reminders that major tech platforms have, time and time again, chosen profit over progress. Their intransigence on robust content moderation allowed for hate speech, conspiracy theories, and disinformation to flourish in the first place, and its effects continue to be felt through their approaches to regulating hate and extremist content online.

While the havoc at the U.S. Capitol tested the will of tech companies to tackle extremism, it has also inevitably become a crucial component of an ongoing discussion regarding regulating these platforms as well. In particular, it has shored up additional support for a conversation about the revision or abandonment of a key piece of legislation regulating tech companies. This provision, known as Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, has long shielded companies from liability for users’ content on their platforms. In the past few years, Section 230 has been challenged by a number of figures across the political spectrum. Trump, in particular, railed against Section 230 as his grip on power weakened, despite having sailed to victory in 2016 partially on the strength of social media. This, in addition to antitrust lawsuits levelled at Facebook and Google in particular, means that the very ground beneath these social networks could be changing — and, along with it, the management of hate speech online.

Expecting and encouraging companies to embrace better enforcement practices when it comes to hate speech online, whether through Section 230 reform or otherwise, is only one part of the solution. “Deplatforming” — a term used to refer to the actions that tech companies take to prevent an individual or a group, often extremists, from using their products — can limit the spread of hate speech effectively across popular social media sites while pushing them to more niche communities. However, when it comes to curbing the threat posed by extremism, these efforts are, on their own, insufficient and temporary fixes.

Without a sustained campaign to promote media literacy and a commitment to dismantling structural and systemic white supremacy, deplatforming efforts could be insufficient at fully stopping the spread of hate online. Biden must push tech companies to consider policies that limit the spread of hate speech, while adhering to human rights laws, as just one part of a broader strategy for addressing radicalization.

2020 moderation efforts came too little, too late

Social media platforms and tech giants, such as Google, wrestled with their policies governing hate speech and disinformation throughout 2020, often while struggling to adapt to and keep pace with the ever-changing landscape of online extremism. Representatives from Facebook, Google and Twitter found themselves having to answer for many of their content moderation decisions in House and Senate hearings throughout the year. While all three platforms continued to develop their hate speech policy throughout the year, there was progress on other platforms as well. The discussion site Reddit, for instance, has booted nearly 7,000 communities, known as subreddits, that it deemed in violation of its new policy on hate speech and harassment since June 2020. Among these were a pro-Trump forum, r/The_Donald, that has been a haven for far-right extremists since 2016.

Other changes included Facebook’s October 2020 pronouncement that it would prohibit content that “denies or distorts the Holocaust.” The move came two years after Facebook founder and chief executive Mark Zuckerberg came under fire for implying that Holocaust deniers may have held their beliefs unintentionally. Platforms also took on the antisemitic, anti-LGBTQ QAnon conspiracy theory. Facebook’s first purge of QAnon groups in August 2020 resulted in the removal or restriction of roughly 3,290 groups and pages on the platform and of another 10,000 accounts on its subsidiary, Instagram. Twitter and YouTube implemented similar restrictions in the latter half of the year.

But these efforts, coming nearly three years after QAnon originated on 8chan, fell short in large part because the conspiracy theory had already taken root in the mainstream. By the time Facebook and other major tech platforms rolled out their policies on QAnon, proponents of the conspiracy theory were campaigning for – and even winning - positions in elected office. Indeed, the SPLC Action Fund counted roughly 90 candidates running for office in the 2020 election cycle who have either shared QAnon content or expressed an openness to the conspiracy theory.

Meanwhile, an NBC investigation found that 1 in 50 tweets about voting in the 2020 elections came from QAnon-affiliated accounts. Trump praised QAnon supporters during an Aug. 19, 2020, press briefing, calling them “people that love our country” who are “against pedophilia” – a wink and a nod to the baseless conspiracy theory at the core of QAnon that Democrats in power run a global child sex trafficking ring. Trump’s own Twitter account had boosted accounts promoting QAnon content on Twitter nearly 270 times by Oct. 30, 2020. These issues came to a head in November, when two vocal proponents of the conspiracy theory — Marjorie Taylor Greene, of Georgia, and Lauren Boebert, of Colorado — won seats in Congress.

Then, on Jan. 6, some of the conspiracy theory’s supporters participated in an insurrection at the U.S. Capitol in an effort to prevent the certification of President Biden’s electoral victory.

These platforms’ struggles with QAnon reflected an even larger problem — specifically one stemming from the executive branch.

Throughout the year, Trump used his caustic social media presence to encourage violence against racial justice protesters; target activists and lawmakers; and call for designating antifascist organizers as members of a terrorist organization. Though Twitter flagged and restricted some of the president’s tweets that it said were “glorifying violence” or promoting electoral disinformation, the president continued to operate otherwise unabated on the platform, thanks to an exception in Twitter’s terms of service that allows the site to preserve access to tweets of individuals they deem in the “public interest.” Trump’s account was finally banned on Jan. 8, 2021, following the U.S. Capitol siege.

In response, Trump and his supporters cried censorship. Bolstered by the myth of conservative censorship online, they launched an attack on a piece of legislation that has been credited with creating the internet as we know it.

The Section 230 controversy

The Trump administration’s war with tech companies, combined with mounting frustration over sites’ inability to police hate speech, has ignited a discussion about the legal protections granted to digital platforms through Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act. These debates came to a head following the attack on the Capitol, with a wide range of observers predicting that changes to the law were now inevitable.

Sometimes referred to as the “twenty-six words that created the internet,” Section 230 provides broad protections to tech companies by shielding them from liability for user-generated content. Proponents of retaining Section 230 have claimed revising or repealing it would have a chilling effect on free speech online. Others have criticized tech companies for not doing nearly enough to uphold their end of the deal.

The former Trump administration and its allies’ efforts to strike down the law dealt with neither of these issues. Instead, it is based on the erroneous and disingenuous belief that Silicon Valley is “censoring” conservative voices. These endeavours have often aligned with Trump’s own violations of Twitter’s terms of service in particular. A May 28, 2020 executive order on “preventing online censorship,” for instance, came after Twitter added fact-checking labels to two of Trump’s election-related tweets. A bill introduced by Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) in June, only a few weeks later, was also framed as a response to supposed conservative censorship.

In his last attempt quash Section 230, Trump vetoed the National Defense Authorization Act in late December 2020 because it did not include language repealing the provision. Congress overrode the veto, but his failed attempt to challenge the tech industry should not stand in the way of real reform.

Informed proposals for Section 230 — excluding those based on ill-informed protestations about censorship — focus on either careful revision or complete reinvention. Biden, for his part, called for eliminating Section 230 at numerous points throughout his campaign — a point that he reiterated in the aftermath of the Capitol siege. Other Democrats have suggested a more cautious approach, even following the Capitol attack. Biden’s nominee for Commerce Department secretary, Gov. Gina Raimondo of Rhode Island, has also publicly backed changes to Section 230, saying that she would pursue changes to the law if confirmed.

Other Democrats have advocated for the same ‘change, but don’t repeal,’ strategy. Rep. Anna Eshoo (D-CA) told Reuters in an October 2020 interview that she’d prefer to use “a scalpel instead of a jackhammer to reform the critical statute,” noting that a complete repeal “is not viable.” Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR), who helped create Section 230 in the 1990s, has advocated for the same care.

“He isn’t saying no one can ever change a word of Section 230, but that politicians need to be very careful when it comes to tinkering with foundational laws around speech and the internet,” an aide to Sen. Wyden told Reuters in the same piece.

Both Democrats and Republicans brought forward several challenges to Section 230 in 2020 and going into early 2021. In March, Sen. Lindsay Graham introduced a measure that would require tech companies to “earn” Section 230 protections. Another measure, brought forward by Sen. Brian Schatz, focused on increasing the transparency and accountability requirements for companies. Lastly, on Feb. 5, 2021, Senate Democrats Mark Warner (D-VA), Mazie Hirono (D-HI) and Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) offered another vision of reform, known as the SAFE TECH Act, which would limit Section 230 protections in cases where payments were involved.

As events such as the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol make clear, the ties between online speech and offline action should be part of any discussion of the future of Section 230. Such changes could provide lawmakers the tools to hold tech companies accountable for their own inaction on managing threats. It would also bring U.S. law on content moderation closer to our European counterparts, who launched their own concerted effort to tackle online harm in late 2019.

Combating hate through media literacy

None of the challenges posed by the years of insufficient and ineffective moderation of online platforms that helped drive the movement that stormed the U.S. Capitol will disappear in the early Biden era. However, as tech platforms grapple with navigating the role they played in the insurrection, as well as the looming possibility of Section 230 reform, it is time to move past simplistic explanations of how extremism online can produce radicalization. Among these assumptions are the idea that deplatforming extremists from tech platforms is, in and of itself, sufficient. Reducing the presence of extremists on platforms can limit their ability to recruit, promote, and fund hate activity. But as the Trump era ought to have demonstrated, it does nothing to address the very aspects of society that make white extremism possible.

Stronger hate speech policies have given rise to a crop of niche, unregulated social media sites that cater to right-wing extremists who have either been booted off or are concerned about being booted off of mainstream social media sites. Some of these, such as Gab and Parler, market to the right wing. But their loose content moderation polices can pose a threat to these platforms’ ability to operate effectively, if at all. The impact these decisions to let hate speech flow freely on a platform was evidenced most recently by Parler’s exclusion from the Apple Store and Google Play — plus the subsequent loss of its host, Amazon Web Services — after it was used to plan, promote and coordinate the Jan. 6 insurrection. Others, like Telegram, have a libertarian approach to content moderation that allows hate to fester. All of these, as J.M. Berger observed in the Atlantic in 2019, can encourage a “pressure-cooker environment where radicalization to violence can take place very quickly.” This is an important phenomenon to track but at present there is no research to prove this. For instance, while many have cited the migration of Trump supporters from mainstream social media sites to Telegram and elsewhere after the 2021 siege on the U.S. Capitol as a possible means of further radicalizing them, researchers have noted that there is no casual evidence to support the argument that these users will be pushed to even more extreme views on these platforms.

Deplatforming cannot fix this problem. However, expanded deradicalization tools can provide an offramp for those looking to leave extremism, while preventative measures can build the support structures needed to prevent radicalization from taking root. Programs that utilize one or both of these strategies have already achieved some success in parts of Europe but also offer a large body of lessons learned and evolving best practices.

In June 2020, the SPLC, in conjunction with America University’s Polarization and Extremism Research and Innovation Lab (PERIL), released a joint report on building resilience against radicalization in the COVID-19 era. When paired with a robust digital literacy program, such as the one developed by SPLC’s Learning for Justice staff, as well as exit programs like Life After Hate, these programs can work hand-in-hand to inoculate or rescue those who are at risk of radicalization or have been radicalized themselves.

Return to The Year in Hate and Extremism 2020 landing page.

Leadf photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images