For Diversity in School Boards: Georgia Students Lead the Fight

Maariya Sheikh is just 16 years old, but every day at school she gets a lesson in inequality she says the adults around her should heed.

Drawn by a specific academic program, Sheikh chose to attend high school outside the affluent, majority-white area of Cobb County, Georgia, where she lives. Her new school is the most racially diverse in the county. It is also significantly less resourced than her middle school. Students, many from disadvantaged neighborhoods, see the difference. Her high school teachers often pay for class materials out of their own pockets. More than two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, they are short of hand sanitizer.

Now, efforts by local and state lawmakers could entrench that inequality by gerrymandering school board member districts – in Cobb County and around the state – to maintain razor-thin white majorities.

Sheikh is one of a growing movement of high school students in Georgia fighting back. Armed with sophisticated organizing techniques and driven by a legislative onslaught from state lawmakers who seem determined to undermine Black representation at every level, they are juggling homework and exams with testimony at school boards and state legislative sessions, betting that by injecting youth engagement into politics run by adults, they can change their own world.

“Crazy things are going on in Georgia,” Sheikh said. “But people are beginning to realize how influential student voices can be. We’re hoping that we can start paving the way for other students to know that they can actually take action about the issues that affect them.”

Students find their voice

A raft of legislation currently on the table in Georgia appears designed to stifle the voices of a student population that, particularly in Atlanta’s metropolitan area, is undergoing rapid change. The Cobb County redistricting proposal, which would entrench a white majority of school board seats in an increasingly diverse county, is one of more than 85 local redistricting bills that have been introduced in the current state legislative session. Separately, conservative state lawmakers have introduced four bills that would limit how race is discussed in schools around the state.

“The Cobb County school board is undergirded by white supremacy which drives many of its policy decisions and has negatively impacted all children in the county, but disproportionately students of color,” said Michael Tafelski, senior supervising attorney for the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Children’s Rights Practice Group, and one of several SPLC attorneys monitoring the developments.

“The three Black Cobb County school board members and the constituents who elected them have been silenced by the four white majority members,” Tafelski said. “It is horrifying to watch the white members disrespect and disregard Black members at monthly school board meetings.”

The students first flexed their political muscle last fall when, during a special session of the Georgia Legislature, state Sen. Clint Dixon took aim at emerging Black political voices in another metropolitan Atlanta county, Gwinnett, the state’s second-most populous. Once predominantly white, Gwinnett is today 27% Black, 23% Latinx and 13% Asian American/Pacific Islander.

Just over a year ago, Democrats became a majority on the Gwinnett school board, and a Black woman took the helm of the board for the first time. Soon after, Dixon went after the new majority, introducing legislation that would have forced the county to adopt new, heavily gerrymandered legislative maps.

By drawing in each case from heavily white areas, the new maps would have diluted the electoral power of communities of color and formed districts more advantageous to white residents. The legislation also would have made Gwinnett school board elections nonpartisan and moved Election Day for them to the municipal off-cycle election calendar, when turnout is much lower and skews older, whiter and more conservative.

Training for justice

Students, about 70-strong, joined with parents to publicize the surprise proposal. Led by Alex Ames, a 19-year-old public policy major at Georgia Tech who began recruiting students to political action three years ago and officially formed the Georgia Youth Justice Coalition in 2020, they publicized the moves to media outlets and searched for allies on social media. In Zoom trainings and in person, the students taught each other the intricacies of state laws. They testified at state legislative hearings and school board meetings.

“As a state that is right on the cusp of being 50% nonwhite, with a powerful, growing, young and diverse population, it’s really important that even though the people drawing these maps have every incentive to draw the lines in ways that silence people of color, that our campus communities and diverse communities across Georgia don’t cede that to them,” Ames said. “So when there was an attack by a representative of Gwinnett County, a white man who does not represent the majority in that county, we helped students find their voices.”

The legislation was defeated. But that did not stop Dixon. This January, the state Senate appointed him chair of a new Georgia Senate Study Committee on school board elections. Soon after, Dixon broke up his former legislation into pieces. The first part, to make the school board elections in Gwinnett County nonpartisan and move Election Day, has already been passed by the General Assembly and signed into law. Further legislation to redraw school board districts, again in ways that advantage white residents, is still under debate.

“We know for a fact that when people of color are able to elect representatives of their choice, they are able to pass policy changes that are positive for their children, and for all children,” said Poy Winichakul, staff attorney with the SPLC’s Voting Rights Practice Group. “And white power doesn’t want that to happen.”

Teaching about race

Today the students continue to fight unfair redistricting. But they have also turned their attention to protecting voting rights and staving off efforts to ban books and comprehensive sex education from school curricula.

It has not been easy. In Cobb County, the school board, still controlled by a 4-3 white majority, does not permit minors to testify unless they are accompanied by a parent. In a number of cases, the majority has failed to give minority board members critical information in advance of meetings. And students say that when they have attended meetings, adults have repeatedly yelled at them.

Last summer, Cobb was one of two school boards in Georgia to pass a resolution banning the teaching of inclusive education, also known as “critical race theory,” in local schools. While the academic framework for examining the way laws and policies perpetuate systemic racism is generally taught only at the graduate school level and not in K-12 schools, conservative lawmakers made the theory shorthand for teaching the legacy of systemic racism in schools and elevated it into a flashpoint in the country’s culture wars.

“The stakes are so high for students, but lots of students are alienated, even scared, to speak out,” said Senait Pirani, 17, a senior at Parkview High School in Gwinnett County who has been involved in the student movement since 2020, when she volunteered to register voters at her mosque. Pirani said that after she testified at a board meeting in August, she and other students were met with vitriolic comments from parents in attendance.

Despite the cruel and bitter criticism, she and other students will continue to speak out, Pirani said.

“We are just kind of continuing our pressure for fair maps,” Pirani said. “We’re kind of hoping that if we say we need fair maps enough, that someone will hear us at the Capitol. Without fair maps, we can’t make any progress.”

Addy Jaramillo, 16, a sophomore in Marietta, said she was driven to get involved in the student movement because of the struggles of her little brother, who is legally blind. Jaramillo was inspired to act after seeing how her brother struggled in the public school system. Now 13, he attends a private school.

“We were able to find a way, but so many families are not,” Jaramillo said. “Having a diverse school board could help increase equal opportunity in the school district and help not just my community, but also other communities in the county, and just create a safer and more suitable learning environment. I just want to be able to go to a school district where everybody is given equal opportunity to learn.”

Tafelski praised the work of the student leaders.

“In our work across the South, we have seen that the most effective advocacy has been led by young people,” Tafelski said. “The students who are impacted by school board policies should be the voices directing how they want those policies to affect them. Our young people are brilliant, creative, strategic and fearless. And we know that systemic change is possible where they lead.”

But for the students, optimism is tempered by frustration – and the belief that Georgia’s children deserve better.

“The fact that we’re fighting now just to be able to speak in these meetings, it makes me angry, but I’m also very sad,” Pirani said. “It just feels like we’re doing the work that should have been done for us. We shouldn’t have to fight in order to get an educational system that allows us to be treated fairly.”

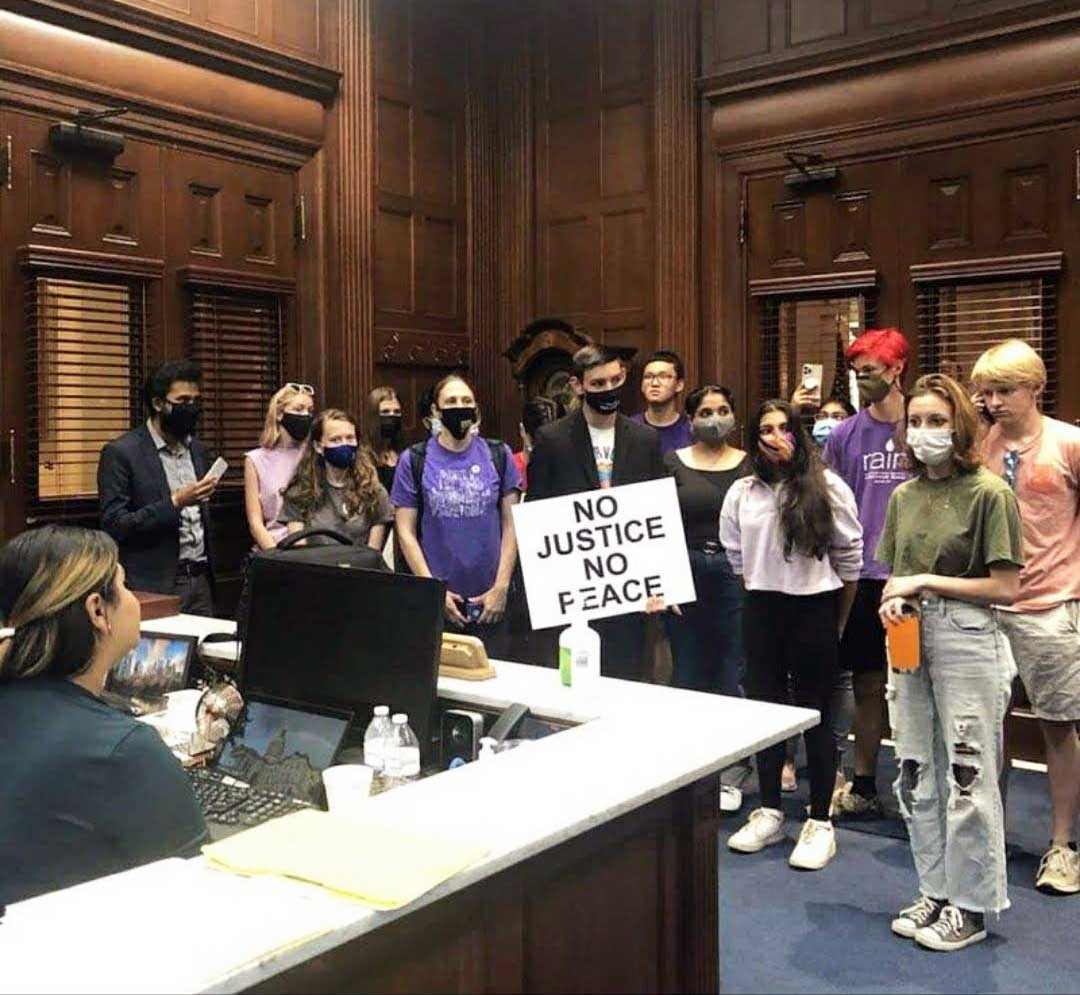

Top picture: Students and parents call for the teaching of inclusive education at a recent event at the Georgia State Capitol in Atlanta. (Courtesy of Alex Ames)