‘Legal Lynching’: ‘Stand Your Ground’ laws reflect legacy of white supremacist vigilantism in Deep South

Content warning: This article contains graphic descriptions of violence. Reader discretion is advised.

The spot where Dominic Jerome “D.J.” Broadus II died from four shots fired by his male paramour was about as secluded as could be.

Hidden at the end of a sandy, private road cut through the vast, ancient, scrub pine forest that surrounds Macclenny, Florida, it was the perfect place to do something that you didn’t want anyone else to see.

There, Gardner Kent Fraser, who is white and from a prominent local family, met Broadus, a Black man, and tried to keep their relationship hidden. Their relationship broke many taboos in this conservative town 28 miles west of Jacksonville.

But the 115 phone calls and over 100 text messages that investigators uncovered between the two men – many of them with sexually explicit photos – showed that their eight-month relationship had grown increasingly tense and troubled. Fraser – who also had a girlfriend at the time – feared Broadus would expose their secret, especially after Broadus played a prank in which he threatened just that.

On Feb. 3, 2018, Fraser shot Broadus dead in a hidden spot behind his house. He claimed to investigators that Broadus – who was unarmed – attacked him and that he shot him in self-defense out of fear for his life. Under the state’s Justifiable Use of Force statute, popularly known as the “Stand Your Ground” (SYG) law, a killer who claims self-defense may be legally immune from homicide charges and not be required to prove that his lethal actions were truly self-defensive. The state attorney declined to prosecute Fraser.

But Broadus’ family members, who have joined forces with state and local activists, say the killing was cold-blooded murder to cover up a socially unacceptable relationship, and that law enforcement has helped hide the truth in order to protect the Fraser family name.

The case highlights racial discrimination in the way SYG laws are implemented.

Broadus’ parents have joined forces with Bob Schlehuber, founder of Peacebuilding Connections, an organization that brings diverse people together in pursuit of nonviolent goals and objectives. Schlehuber, along with the Broadus family and a range of community organizations, has launched a Justice4DJBroadus publicity campaign of protests, marches, community meetings and social media. The campaign also plans bus tours to Macclenny from Tallahassee and Jacksonville to raise awareness of the case.

The tours will preview an upcoming civil trial in the wrongful death lawsuit Broadus’ father has filed against Fraser and his family’s company.

Legacy of Jim Crow

Krista Dolan, senior supervising attorney for the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Criminal Justice Reform Project, said SYG laws are consistent with the country’s racist criminal justice system and the legacy of Jim Crow.

“The discriminatory impact of ‘Stand Your Ground’ laws on Black victims exacerbates a legal system that is already wrought with racial inequity: Nonwhite people are stopped, racially profiled, searched and arrested by police at higher rates than white people and more likely to be sentenced to greater terms than white people,” Dolan said.

While there is no current, granular data to show how many Black men and boys have been killed in Florida by white people who have claimed self-defense, the Tampa Bay Times in 2013 published its analysis of 200 cases. It concluded that the law was not applied equally by race and that when the victim was not white, the killer was more likely to escape punishment. It found that “in nearly a third of the cases … defendants initiated the fight, shot an unarmed person or pursued their victim – and still went free,” and “73% of those who killed a Black person faced no penalty compared to 59% of those who killed a white person.”

In the years since, researchers have consistently concluded that SYG laws result in more homicides rather than fewer and that the laws are more rigorously enforced when the victim is white.

‘Justice delayed is justice denied’

The COVID-19 pandemic interrupted the campaign demanding justice for D.J. Broadus, but it resumed in late 2022. The campaign has partnered with Black Lives Matter Tampa in collaboration with the Rev. Russell Meyer, director of the Florida Council of Churches, and with the Working Families Party, all of which have provided financial support. Other supportive groups include Dream Defenders, the Jacksonville Community Action Committee, Tallahassee Community Action Committee, and Florida college students with Students Demand Action (SDA) and Moms Demand Action.

The groups are seeking to repeal or reform the SYG law.

In early 2020, Broadus’ father, Dominic Broadus Sr., filed a wrongful death civil lawsuit against Fraser and his family’s business, Southern States Nurseries Inc., on behalf of his son’s estate and D.J.’s 15-year-old son.

The civil trial was scheduled to begin on May 1, 2023, but on Feb. 7, a new judge assigned to the case postponed the trial until Oct. 30, citing Southern States’ failure to provide all pretrial materials requested by Broadus’ attorney. The company also requested that the judge dismiss the company as a defendant.

“Can you imagine, you don’t do your homework and you get a five-month extension?” Schlehuber said. “Justice delayed is justice denied.”

Before the delay in the civil trial, Schlehuber was planning bus tours of Baker County’s Confederate iconography and historical sites linked to the area’s white supremacist legacies. In addition to seeking the repeal or reform of SYG laws, he hopes that widespread media attention will pressure the new state attorney to reopen the case and ultimately charge Fraser with Broadus’ death.

“Florida’s legal system has postponed, canceled, delayed and used every stall tactic in the book to prevent the Broadus family [from having] its day in court,” Schlehuber said. “But we will not be deterred. … In many ways we were expecting it, even though delays like this in a civil trial are rare. The strategy and plan moving forward remains unchanged. It is just that our timeline has shifted.”

Black parents live in fear

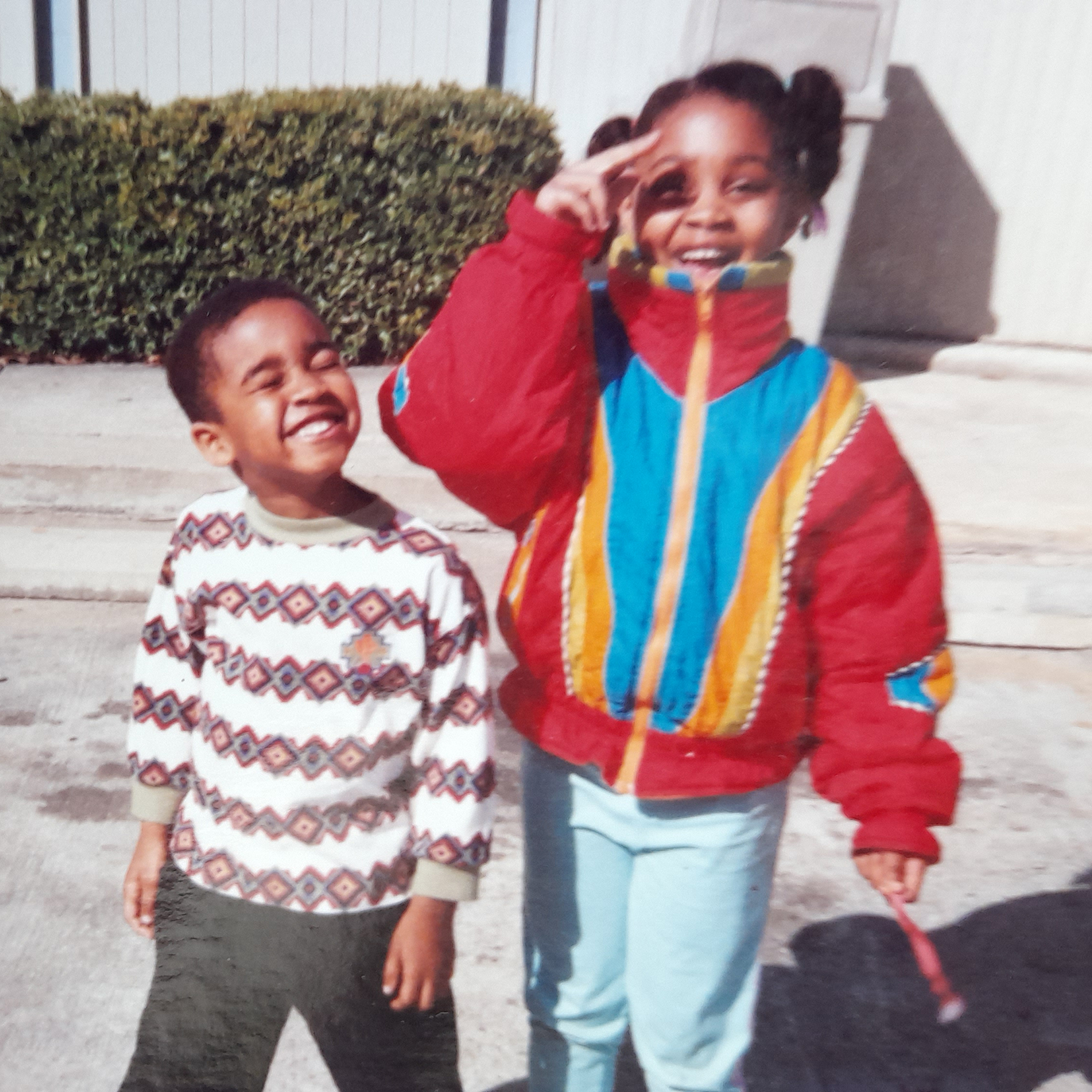

For most of his childhood, Broadus lived in Anniston, Alabama, during the school year with his mother, Del Swain, then a speech pathologist, and an older sister and, eventually, a younger half sibling. He spent summers and holidays in Jacksonville with his father, an environmental engineer for the U.S. Navy.

Like many other Black parents in the U.S. – especially mothers – his parents always feared for their children’s safety.

“I always thought that my kids could possibly be hurt by the hands of someone evil as they lurk around every corner in America,” Swain wrote in a series of emails to the SPLC from her current home in Europe.

“When it comes to the false narrative of the ‘American dream,’” Swain said, “it’s certainly not a dream. It’s a nightmare.”

When Broadus was 15, Swain asked his father – who was to be posted in Naples, Italy – to take their son with him, believing the teen would benefit from his father’s influence and be safer than in the U.S. Since the sixth grade, Broadus had complained to his parents about racism in school.

Over the years, both parents drilled into their children a set of “tactics and rules” – as Swain calls them – to safely navigate the “dysfunctional world” where she was raising her children: Be cautious; be home before dark; don’t make trouble.

“You can listen to rap music, but you can’t live your life like that,” Dominic Broadus Sr. said he counseled his son.

He vividly remembered as a young boy his own father telling him about Jim Crow and segregated drinking fountains. He told his son, “You see police pulling people over – you have to be careful. You don’t want to get killed before you get out of high school.”

After graduating from high school in Italy in 2005 and spending several years in Kentucky, Broadus reunited with his father in Jacksonville in 2009. He attended community college for a time but dropped out when the Great Recession hit and he needed to work to support his own budding family. Later, he was laid off and was arrested for selling marijuana.

Keeping secrets

The need to protect the secrecy in the relationship between Broadus and Fraser stemmed not only from the sexual nature of their meetings, but also the fact that Fraser is from a generationally well-connected family that owned the land where their final encounter took place. Further, Fraser lived and worked at his family’s nursery stock business.

Fraser’s father, who at the time of Broadus’ death had just retired as a sheriff’s deputy, was fired from the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office in 2009 for shooting an unarmed Black man who posed no threat. Fraser’s great-uncle, J.E. Fraser, was the reputed grand wizard of the 30,000-member-strong, largest state order of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1950s.

A great-grandfather was a former state senator for whom the Macclenny hospital is named. Other ancestors, too, were movers and shakers.

‘Tampering with evidence’

There was no witness to Broadus’ killing – a homicide, the medical examiner and state attorney concluded. There was no video showing Fraser shooting his victim four times behind his house: two shots to Broadus’ lower face while both men were standing, and the second two as Broadus lay on the ground bleeding, point-blank, one centimeter apart, behind his left ear, perforating his spine, according to the Florida Department of Law Enforcement (FDLE) Investigative Summary.

There were no signs of a physical scuffle either, according to the FDLE report, despite Fraser telling police that Broadus knocked on a door of his house and attacked him when he opened it.

There were no images of Fraser turning Broadus’ body from his right side over onto his back sometime during the 21 minutes before he called 911, during which time he called his cousin, father and sister.

There was no proof that the killer took Broadus’ cellphone from his motionless, clenched hand, which bore the phone’s imprint. The phone vanished from the scene and was never found.

And there was no crystal-clear answer to the question of the true motive for the killing: Did Fraser – who first denied knowing Broadus, then told sheriff’s deputies that it was “a practical joke from a couple of weeks ago gone bad” – kill Broadus because he believed his victim planned to expose him?

In 2021, nearly two years after the killing, Fraser was sentenced to the maximum one year in prison for “tampering with evidence.”

‘It was a joke’

The relationship between Fraser and Broadus began to deteriorate in December 2017.

After Fraser failed to show up for a planned encounter at a hotel and stopped responding to Broadus’ text messages and explicit photos, Broadus played a prank on him.

Pretending to be a stranger and using several pseudonyms, Broadus posted a photograph of Fraser in women’s underwear on a Craigslist forum for gay men.

Broadus removed the post from the site right after taking a screenshot of it, then texted it to Fraser, pretending to be the stranger who had seen the post. In response, Fraser told the supposed stranger that he had sent the photos and texts himself – “I was being funny and led this Black guy on” – and that “it was a joke.”

But the fake outing ramped up. The “stranger” told Fraser that a Black man was at the local Walmart parking lot, handing out Fraser’s email, address, phone number and pictures of him in women’s underwear. At some point, the stranger texted, “But does his family and friends know??? It’s time for him to be exposed.”

The prank amplified Fraser’s fears that Broadus would “out” him, according to Caroline Light, a historian who studies gender, sexuality and racial violence at Harvard University and the author of the 2017 book Stand Your Ground: A History of America’s Love Affair with Lethal Self-Defense.

Light has been studying the Broadus case since 2019 after the state attorney declined to charge Fraser with homicide and Broadus’ family consulted her. She and Vice Media, which is filming a documentary about the case, obtained the recovered texts, photos, call transcripts and videotaped interviews conducted by the sheriff’s department through joint Freedom of Information Act and evidence records requests.

Light also contends that the Broadus killing and Fraser’s subsequent evasion of punishment is a perfect example of the dangers and racial injustice of self-defense claims under SYG laws. Killers can invoke SYG law after a homicide, and it’s up to the state to prove that the killer was not acting in fear for their life. In an interview with the SPLC, Light called SYG laws “vigilantism disguised as self-defense” – a kind of “legal lynching” consistent with “historical structures of white supremacist and patriarchal power.”

The broad, self-defense Justifiable Use of Force statute in Florida was first enacted in 2005. Thirty-seven other states have similar laws, with the strong backing of the National Rifle Association (NRA). (The NRA is among pro-gun organizations that offer self-defense insurance policies to gun owners involved in crimes.) These laws often enable white killers to escape punishment, particularly when they kill a Black man or youth. Unless the case evidence – such as a video, explicit audio, or a first-person witness account – proves without a shadow of a doubt that the killer is lying, he can escape punishment by asserting that he committed the killing in self-defense.

‘License to kill’

Although a legal exception for deadly self-defense in a shooter’s home already existed, Florida’s law gutted a centuries-old legal standard that someone in fear for their life has a duty to retreat before using deadly force.

The state’s self-defense standard came under intense national scrutiny in 2012 after 17-year-old Trayvon Martin, who was Black and unarmed, was fatally shot by neighborhood watchman George Zimmerman.

Five years later, lawmakers expanded the immunity standard further by removing the burden of proof from the defense and placing it on prosecutors, who must disprove the self-defense claim. This innovation “discourages prosecutors from filing criminal charges when someone invokes the claim pretrial,” the SPLC’s Dolan said.

As Light puts it, the killer claims the mantle of self-defense by framing himself as the victim, even when he was the initial aggressor. The law allows the roles of perpetrator and victim to become reversed.

Police, too, are discouraged from making arrests when a killer claims self-defense, Light said, because under the law they can be sued for false arrest if the killer is later found to have been in reasonable fear for their life.

In the Broadus case, the state attorney cited a lack of sufficient state evidence to disprove the killer’s claim of self-defense.

National gun control organization Everytown, which fights to repeal or amend the SYG law through its Florida chapters of Moms Demand Action and Students Demand Action, calls the law “a license to kill.”

‘Keep the faith’

In the aftermath of their son’s death, Swain and Broadus Sr. contacted Marcus Arbery, whose 25-year-old son Ahmaud Arbery was murdered in 2020 by two white men with a white accomplice while he was jogging unarmed in his South Georgia neighborhood. Were it not for three separate videos of the moments before, during and after the murder that surfaced nearly two months later, the trio would likely have escaped prosecution and conviction, because they invoked “self-defense” and were not initially charged.

“It’s hard to get justice for Black people if there is no video,” Marcus Arbery told the SPLC.

“For us to get justice, it meant a lot to me and his mother. Look at Trayvon, Eric Garner, Breonna Taylor – we can’t bring our little ones back, but you have to make them [the killers] accountable. It takes a little of the pain off if you know they are paying for it, because when you don’t, it really hurts. I just tell D.J.’s parents they have to keep the faith with God and don’t give up.”

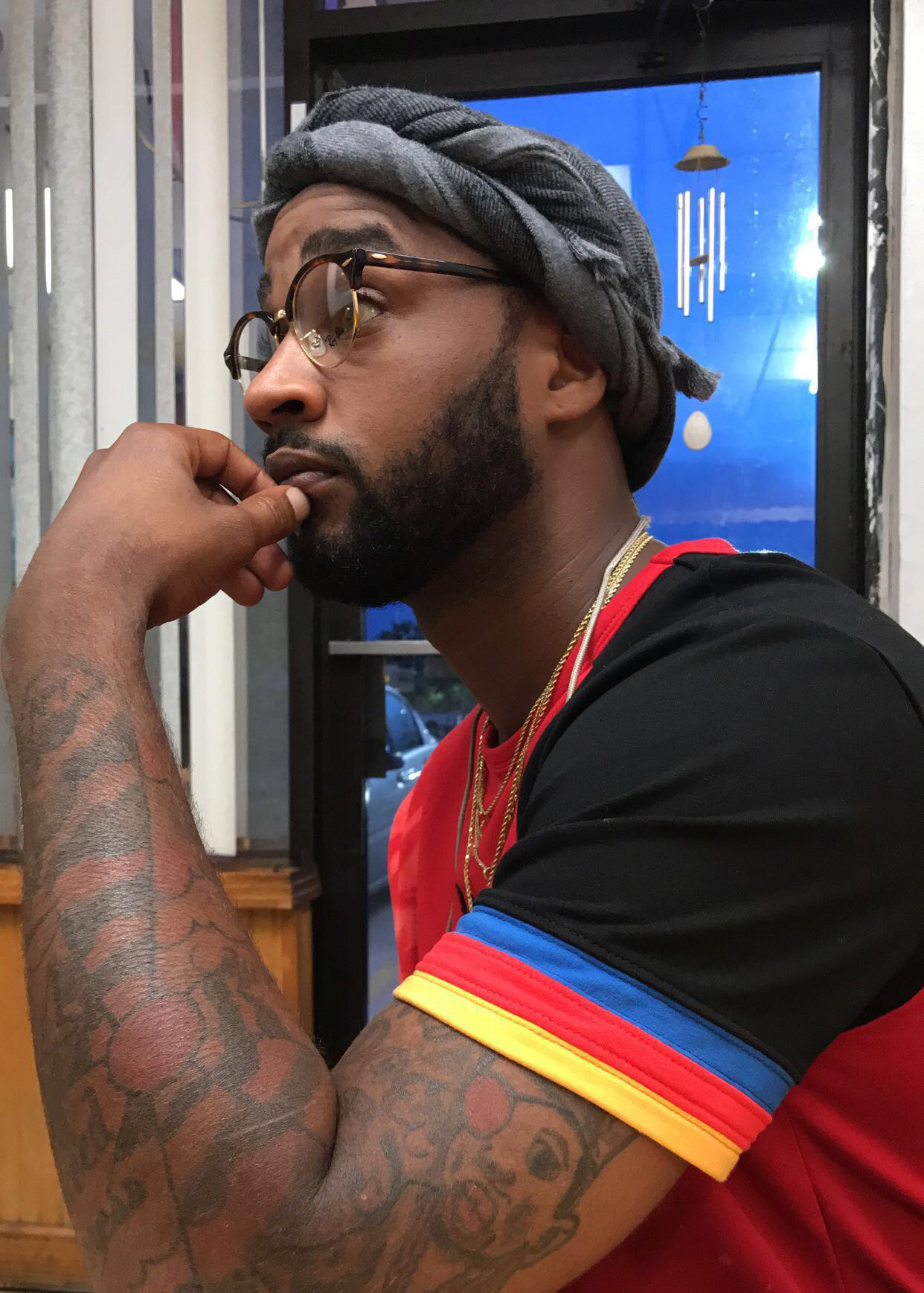

Photo at top: On Feb. 3, 2018, Dominic Jerome Broadus II was fatally shot in Macclenny, Florida, by Gardner Kent Fraser, who claimed self-defense and was therefore legally immune from homicide charges. Five years on, Broadus' family and community activists continue to seek justice via a campaign of protests, marches, community meetings and social media. (Credit: Emil Ashok)