Coalition trains advocates of children with disabilities in Mississippi

Kate Centellas and her husband, Miguel, are professors at the University of Mississippi in Oxford. They have three children and live in a comfortable, upper-middle-class suburban house in a professional family neighborhood.

Kate will tell you matter-of-factly that she is white, well-educated, financially secure and “privileged.”

She will also tell you that even with those considerable advantages, she has had to wage a relentless, yearslong battle with the Oxford School District to ensure that her daughter Zoe, who has autism and is soon to be 14, receives the special education (SPED) services she needs and which the federal government requires under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

Under the IDEA, each state and its school districts must provide children with disabilities a “free appropriate public education” and “special education and related services.”

Yet for 18 months after Zoe was diagnosed with autism in 2020, she received no autism-specific treatment.

After a breakdown in 2021, Zoe spent 18 months at an all-day, locked and restricted outpatient treatment center at the district’s expense, but her parents felt that she was being “warehoused.” They wanted the academics, structure, socialization and SPED services they believed a public school could provide. After getting nowhere, Centellas took family leave and then a deferred sabbatical.

“Advocating for my daughter became my full-time job,” she said.

Every day, parents across Mississippi experience similarly daunting struggles because most school districts fail to comply with state and federal law.

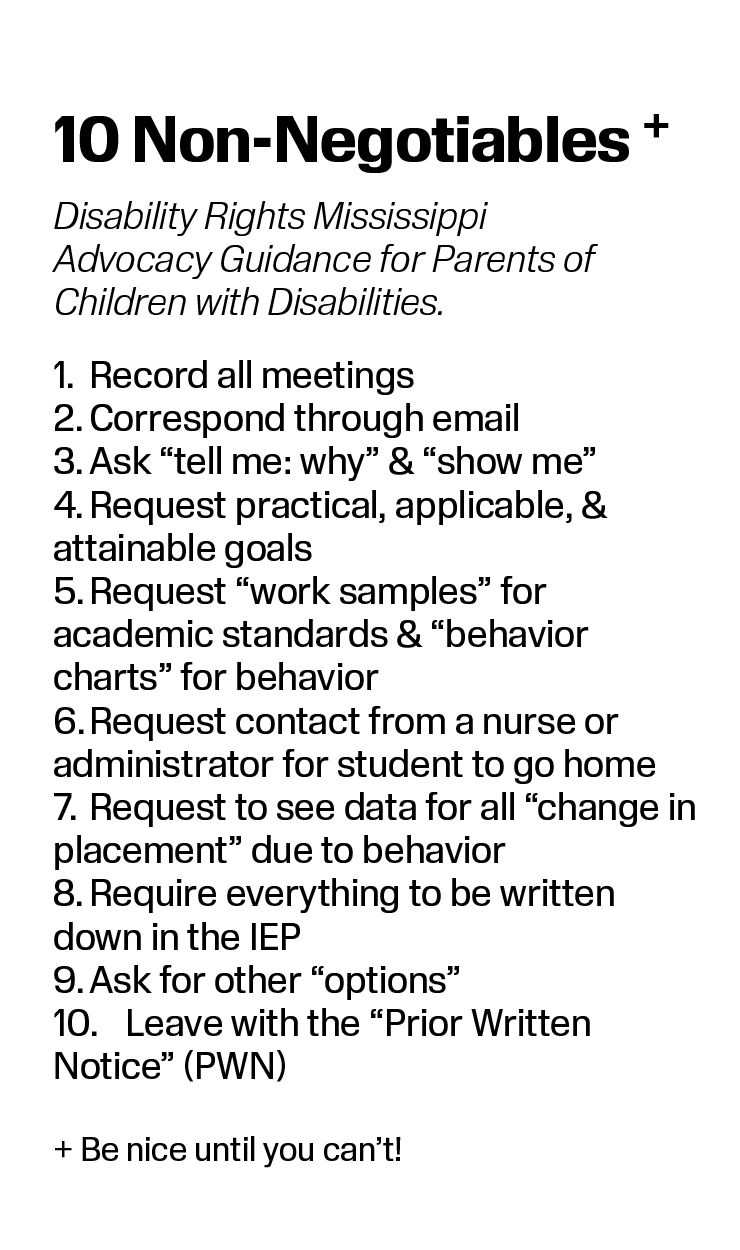

To address the dire need for child disability attorneys to help parents navigate these challenges in Mississippi, the Southern Poverty Law Center last month co-sponsored a special education legal clinic in Oxford along with coalition partners the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), the ACLU of Mississippi, Disability Rights Mississippi (DRMS) and the private law practice of Frye Reeves. The clinic provided training for lawyers interested in representing families, for advocates who help parents navigate the system without an attorney and for parents who need to know their rights under the law.

The coalition plans to hold clinics at least three times each year, rotating between the northern, central and southern regions of Mississippi.

The SPLC has also created a guide for parents of children with disabilities titled “Helping Your Child With a Disability Get a Good Education,” including state-specific guidance for parents in Louisiana and Mississippi.

“Mississippi is the worst state in the nation for providing SPED for children with disabilities,” said Julian Miller, senior supervising attorney for the children’s rights department at the SPLC and one of the state’s leading attorneys for child disability rights.

“The district has the obligation to locate, identify and evaluate any child for a disability, no matter whether they are in public, private or home schooling. Their failure to provide SPED can be intentional, particularly in wealthier districts that prefer to litigate because they want to be exclusionary and keep up their graduation rates.”

Cases not adjudicated

In the most egregious cases, the back-and-forth between parents and school districts can drag on for years.

In one of the more than 35 open education cases that DRMS was investigating last year on behalf of parents, one district held back a student with disabilities three times. By then, he was 13 years old and sharing classes, bathrooms and the schoolyard with children who were 10. State Department of Education guidance calls for a maximum age difference of only two years between classroom peers. Larger disparities in age can lead to teachers, staff and parents of younger children in the class to accuse the older student of acts he never committed, DRMS children’s rights attorney Andy Robison said.

Currently, there are no more than 10 attorneys in the state who work in this less-lucrative niche of civil rights law, said attorney Janet Goode, who has two child disability cases in federal court now and attended the clinic.

Additionally, numerous Mississippi districts have banned non-lawyer advocates, which is illegal under the IDEA. And because Mississippi has the highest poverty rate in the country, relatively few parents here are able to hire a private attorney to file a due process complaint with the state. Parents may also have disabilities that can complicate their ability to advocate on their child’s behalf.

“The solution is to build a coalition with parents, advocates and lawyers for effective representation for their children,” Miller told about 50 clinic attendees.

In the video: The Southern Poverty Law Center co-sponsored a special education legal clinic on Aug. 8, 2023, in Oxford, Mississippi, along with coalition partners the American Civil Liberties Union, the ACLU of Mississippi, Disability Rights Mississippi and Oxford law firm Frye Reeves.

“These cases aren’t adjudicated enough,” he said. “There are an insufficient number of lawyers and a lack of [legal] precedent and regulatory enforcement. That’s why we’re here today. We want to get to that point where we have more lawyers involved, more compensatory services and more legal precedent from the [federal] 5th Circuit.”

Trouble from the start

Children with disabilities in Mississippi numbered almost 70,000, or 14.7%, of the approximately 478,000 children in public schools in 2019, the most recent data available. That number places it at about the national average. By race, white and Black children with disabilities were fairly evenly divided, each comprising about 48% of cases.

Under the law, districts must have every child with a disability formally evaluated by one or more teachers and experts. Then the school districts must create an Individualized Education Program (IEP) in collaboration with parents that specifies the SPED services the child will receive. Under the law, IEPs are supposed to be revised based on whether the child meets their benchmarks and goals.

The IDEA and SPED services are supposed to be funded by the federal government, and states and local governments are required to match the funding. However, the federal government consistently underfunds the mandate, and the number of students with IEPs and the cost of services has increased dramatically in recent years.

Still, in a legal dispute, local districts are prohibited from using a lack of financial resources as an excuse for providing inadequate services. Lawyers, parents and advocates say that districts often lie outright to parents and tell them that the IEP is already providing the services their child needs or that the district cannot provide them because there are no local service providers.

“Every problem parents of special needs children face starts with the comprehensive evaluation, because the data is not translated to the IEP and used as the basis for its development,” Miller said. “Furthermore, evaluations are often not sufficiently thorough and comprehensive.”

If a child demonstrates disabilities not in the IEP, parents are then forced to battle districts to reevaluate the child and modify the IEP. Children may demonstrate three or four of the 13 recognized disabilities over time, though the IEP may only list one or two due to lack of evaluation thoroughness. Or the IEP may not separate a behavioral issue stemming from, for example, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), apart from their recognized hearing disability. That omission can result in a child’s repeated removal from school for disciplinary infractions when the actual underlying problem is the lack of PTSD treatment.

Other blatant violations of the law include districts’ failure to evaluate the child at all; failure to place the child in a “least restrictive environment” – a regular classroom with peers who do not have disabilities – rather than in a “self-controlled classroom,” where children can be isolated for days, weeks or months at a time, without sufficient SPED, socialization and education.

Racial bias in treatment?

Children who spend more time at home after expulsions are more likely to experience regression in their abilities, most often language and speech, cognition, social or behavioral learning, Robison said.

Even so, districts often keep the children who most need support services at home.

“In comparing academics to behavior, districts would never say you can come back to school when you learn your multiplication tables, but that is what is done every day concerning behavior,” said Tammy Crane, a children’s advocate at DRMS.

“Students are told when you act right, you can come back. Unfortunately, for many students that day never comes.”

It’s also not unusual for schools to falsify a child’s official records by not recording when they are sent home or are absent due to expulsion.

“We will ask for a kid’s school records, and if we notice that the kid has a near-perfect attendance, the parent will tell us that the kid is at home,” Robison said. “Nine times out of 10, the reason for sending a child home is disciplinary, or they send the child home, never arrange for their return to school, and the child or parent wants them to go back. I had one kid at home for a year without supportive services before mom and dad realized something is wrong and they need help.”

Based on client intakes at DRMS, Robison believes that children of color are placed in self-contained classrooms more often than white children. He and DRMS staff are in the process of gathering that data to determine whether there are, in fact, racial disparities in IEPs.

“Districts deny systemic racism up and down,” Robison said. “We see ‘emotionally disabled’ – one of the 13 eligibility areas – disproportionally applied to Black students in their IEPs. They [teachers and administrators] are habituated to it. Mistreatment has been allowed to happen for generations.”

Districts also commonly fail to provide properly trained American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters for children with speech and hearing disabilities. And in the increasing cases of autism over the past decade, districts fail to provide board-certified behavioral analysts and registered behavioral technicians to give behavioral therapy.

“Autism cases are litigated so often because the child is misdiagnosed,” Goode said. “If they are high-functioning, the district will say that they are fine. I see this frequently.”

‘Parents are coming to us’

Attorney Kevin Frye, whose law firm co-sponsored the clinic, began representing children with disabilities after his 6-year-old son Nathan was born with a rare genetic mutation that leads to autism. He said districts downplay the importance of parental input. They frequently tell parents that they will provide the same services they provide to other children with the same category of disability, although each IEP, by law, is required to be individualized.

“The system is designed to do what they’ve been doing for years,” said Frye. “The administration told us what they were going to do for Nathan, but it was clearly the party-line answer. We had seven IEP meetings and the last one included 25 people – school staff, administration, specialists, a district lawyer and my own lawyer. We all spent a lot of money, but we got what we asked for from the beginning. Since then, I’ve talked to three different sets of parents, and the administration has told them the same thing they told us in the beginning.”

Parent Whitney Reeves, a former SPED teacher, attended the clinic with her husband to learn how she can more effectively advocate for her son Braxton. He has a severe hearing disability yet receives only 20 minutes a day of hearing and speech therapy. Braxton has no teachers trained in ASL, and an ASL interpreter comes just two days per week, while Reeves said her son needs one full time.

At his evaluation, Braxton had no ASL interpreter and could not communicate with the evaluator. During the COVID pandemic, Reeves held her son back a year because he was receiving no services. One special-ed teacher told her, “I don’t know what the issue is. He can [legally] stay in school till he’s 21.”

“The district isn’t willing to budge,” Reeves said. “When you walk into a meeting, they already have a plan. They say that the parents are only one part, that ‘we have a big committee and we all agree on the plan.’”

Alexis Jones, an adult with disabilities who is an advocate for children with special needs as well as a former SPED teacher, said that one of the biggest problems she sees is that parents don’t know their rights under the law and are misinformed by districts that “use [lack of] money as a justification for lack of services.”

“This past year alone, I know of 20 kids in one large district where parents were being talked out of their child having an IEP and into a 504, which only provides accommodations to the child, not an individualized instruction with services,” she said. “They told parents that the IEP doesn’t follow a student to college, but a 504 does. That’s BS. I believe it’s intentional from the district heads who think, ‘We need to manage our finances,’ because a 504 doesn’t cost the district money but the IEP does. There needs to be better monitoring of how the funds for special education services are being allocated. In addition, the school staff and administration need to be properly trained in order to provide the services these students need.”

More help is coming

Despite years of complaints and legal challenges to the Mississippi Department of Education’s implementation of the IDEA, the federal Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) has not monitored the state’s IDEA compliance more often than the federal six-year legal requirement.

On Aug. 16, the coalition learned that the OSEP will launch a compliance audit in April 2024 – two years earlier than scheduled – and will begin gathering information this November.

Clinic coalition partners will be ready.

“We have come to this work after reports from parents around the state struggling with school districts,” said Claudia Williams Hyman, senior staff attorney for the ACLU of Mississippi, a clinic co-sponsor. “Our model focuses advocacy on impact, not on direct service. We are building relationships with attorneys and advocates who work with parents.”

Today, through Kate Centellas’ dogged advocacy, her daughter Zoe is back in public school with three resource teachers every day.

During a panel discussion, Centellas told parents to be “more proactive.”

“Advocating for Zoe has illuminated the system’s structural issues,” she said. “A doctor told me that Zoe was eligible for Medicaid, which opened her up to more special-ed services, but no one in the district ever told us that. Especially in the South, it can be especially hard to push back against due to racism, sexism, classism and the expectation of respecting authority.”

Her husband, Miguel Centellas, agreed.

“I’ve often met parents who didn’t even know a service was available until I mentioned it to them, even though their children were in the same school as our Zoe. I can only imagine how unlikely parents of ESL, lower-class or other marginalized peoples are to know what to even ask for from their school,” he said.

“This experience has radicalized my husband and me,” Kate Centellas said. “It has been very hard but much easier than other stories I’ve heard.”

Photo at top: Julian Miller, senior supervising attorney for the children’s rights department at the SPLC, leads a special education legal clinic on Aug. 8, 2023, in Oxford, Mississippi. (Credit: Caleb Nelson)